Here is the radio show companion to my March 13th & 20th and June 19, 2025 articles in the Weekly View newspaper, all of which are available to read on this site.

Here is the radio show companion to my March 13th & 20th and June 19, 2025 articles in the Weekly View newspaper, all of which are available to read on this site.

Original publish date June 19, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/06/19/nazi-ideology-on-the-eastside-a-contnuance/

Last March, I wrote a two-part article on Eastsider Charles Soltau, the “Nazi at Arsenal Tech”. This Saturday (June 21st) at noon, I will revisit those articles on Nelson Price’s “Hoosier History Live” radio show WICR 88.7 FM. Nelson, a longtime friend of Irvington, has a personal connection to that story, which he will share for the first time ever during that broadcast. As it happens, weeks after that article appeared, quite by accident, I ran across a few documents that spoke directly to that time in Indianapolis history.

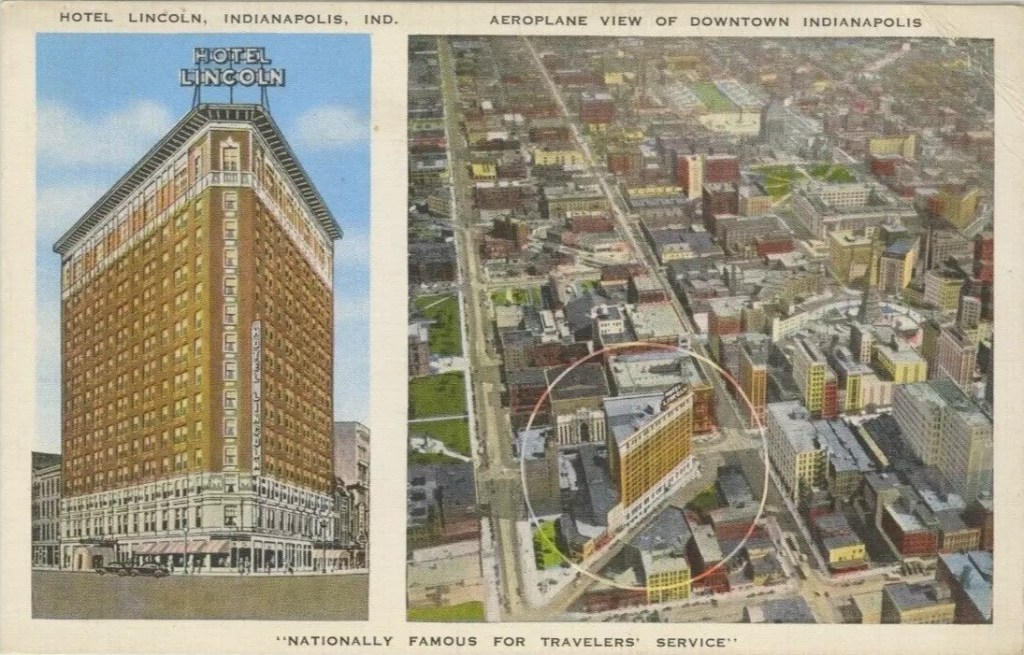

While perusing a few boxes of vintage paper at a roadside antiques market, I found a pair of cards from February 1938, advertising one of the first 35 mm camera photo exhibitions in Indianapolis at the Hotel Lincoln. The Hotel Lincoln, built in 1918, was a triangular flat-iron building located on the corner of West Washington St. and Kentucky Ave. The hotel was named in honor of Abraham Lincoln, who made a speech from the balcony of the Bates House across the street in 1861. Afterwards, that block became known as “Lincoln Square.” The Hotel displayed a bust of Abraham Lincoln on a marble column in its lobby for decades. The Lincoln was a popular convention center and was once the tallest flat-iron building in the city. The Lincoln was the site of the arrest of musician Ray Charles (a subject covered in depth in one of my past columns). It also served as the headquarters for Robert Kennedy and his campaign staff, who leased the entire eleventh floor of the hotel during the 1968 Indiana primary. The Lincoln was intentionally imploded in April of 1973.

It was the Hotel Lincoln’s history that originally piqued my interest. The front of each card read, “You are invited to attend the Fourth International Leica Exhibit on display in the Hotel Lincoln, Parlor A, Mezzanine Floor, Indianapolis, Ind., from February 23 to 26 [1938], inclusive. Hours: 11 A.M. to 9 P.M. (on February 26, the exhibit will close at 5 P.M.) More than 200 outstanding Leica pictures will be on display, representing the use of the camera in various fields…Candid, Amateur, Commercial, Press and Scientific Photography. Do not fail to view this show which represents the progress in miniature camera photography throughout the year. Illustrated Leica Demonstration will be given at the American United Life Insurance Co., Auditorium, Indianapolis, February 24, 8:30 P.M. by Mrs. Anton F. Baumann. ADMISSION FREE. E. Leitz, Inc. New York, N.Y.” Research reveals that the winner of the contest was W.R. Henkel, who resided at 2936 E. Washington Street. Henkel received the Oscar Barnak Medal, named for the inventor of the Leica camera.

The Leica was the first practical 35 mm camera designed specifically to use standard 35 mm film. The first 35 mm film Leica prototypes were built by Oskar Barnack at Ernst Leitz Optische Werke, Wetzlar, in 1913. Some sources say the original Leica was intended as a compact camera for landscape photography, particularly during mountain hikes, but other sources indicate the camera was intended for test exposures with 35mm motion picture film. Leica was noteworthy for its progressive labor policies which encouraged the retention of skilled workers, many of whom were Jewish. Ernst Leitz II, who began managing the company in 1920, responded to the election of Hitler in 1933 by helping Jews to leave Germany, by “assigning” hundreds (many of whom were not actual employees) to overseas sales offices where they were helped to find jobs. The effort intensified after Kristallnacht in 1938, until the borders were closed in September 1939. The extent of what came to be known as the “Leica Freedom Train” only became public after his death, well after the war.

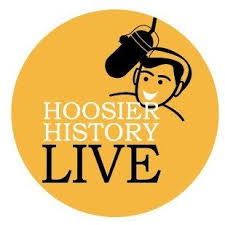

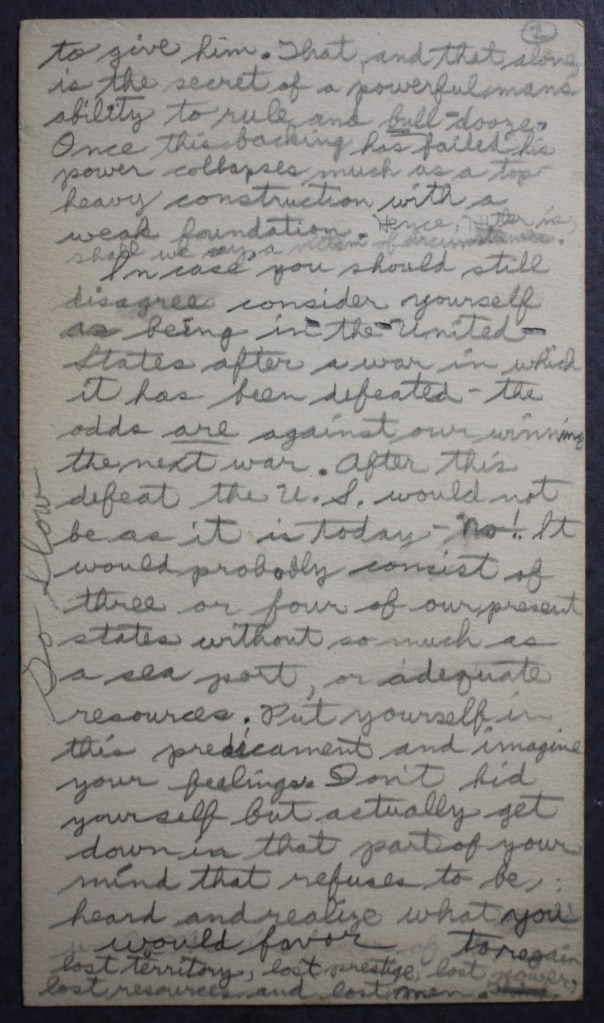

While my interest was drawn to the printed text, it was the handwritten pencil notations on the back of the cards that sparked that purchase. The cards contained a contemporary essay about the political atmosphere in the Circle City less than a month after the Soltau family’s Nazi incident. Written in pencil, the cards, numbered 1 and 2, read: “Hitler! Hitler Dictator of Germany! Is he to blame for the present aggressive stand of Deutchland? No! He is not. Directly, it is the German people that are to blame but additionally and more importantly, this aggressive attitude is the result of the great war to “make the world safe for Democracy!!” This is only a natural outcome of any war, whether large or small. After a war there is a spontaneous decline of morals. This is particularly evident on the defeated side because they have lost men, money, power, land, and consequently, resources. At the lowest ebb of a people’s hope they look to a leader, a strong, fearless, aggressive man. When this superman is found, the people raise him to great heights as their leader. One must remember that a dictator, or any other national leader, has only the power that his people are willing to give him. That, and that alone, is the secret of a powerful man’s ability to rule and bulldoze. Once the backing has failed, his power collapses much as a top-heavy construction with a weak foundation. Hence, Hitler is, shall we say, a victim of circumstance. In case you should still disagree, consider yourself as being in the United States after a war in which it has been defeated; the odds are against ever winning the next war. After this defeat the U.S. would not be as it is today. It would probably consist of three or four of our present states without so much as a seaport or adequate resources. Put yourself in this predicament and imagine your feelings. Don’t kid yourself but actually get down in that part of your mind that refuses to be heard and realize what you would favor to regain lost territory, lost prestige, lost power, lost resources, and lost men.”

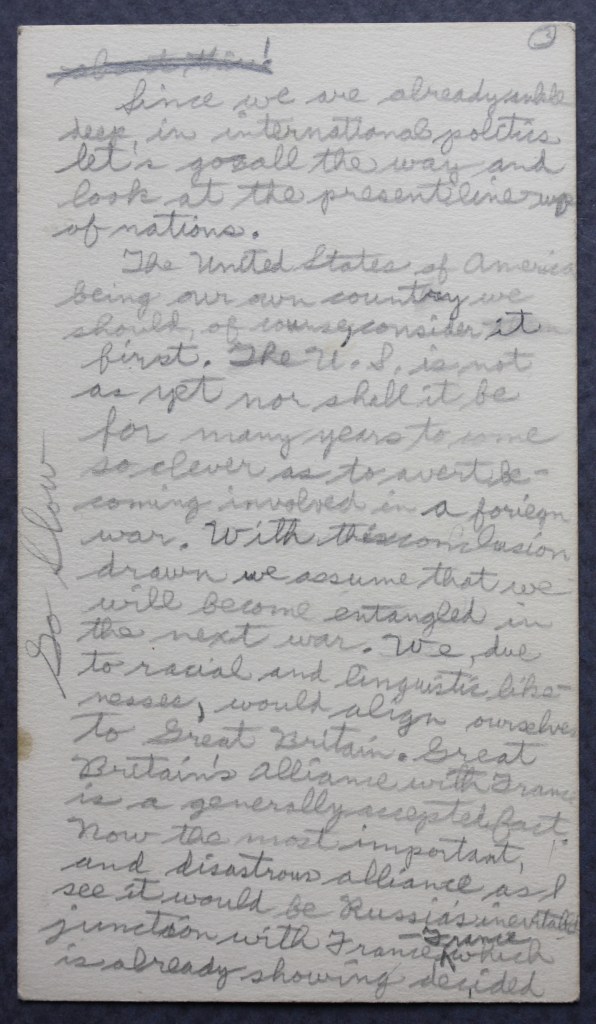

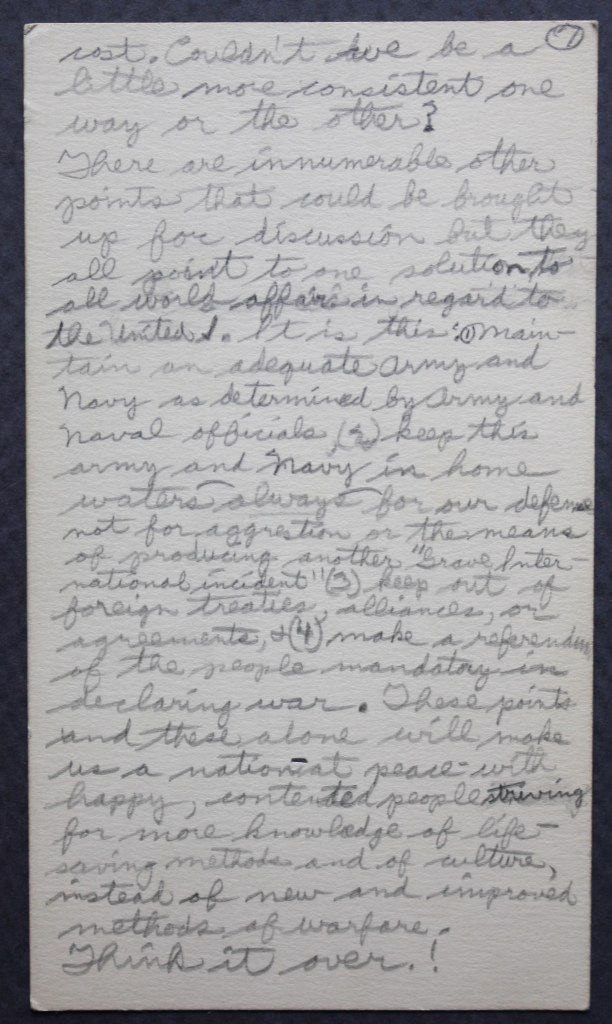

The next week, I revisited that roadside market. Lo and behold, the same dealer was there, and he brought more boxes of paper. I found two more of those cards, numbered 3 & 7, with more of that essay featured on the reverse. “Since we are already ankle deep in international politics, let’s go all the way and look at the present lineup of nations. The United States of America, being our own country, we should, of course, consider it first. The U.S. is not as yet, nor shall it be for many years to come so clever as to ever become involved in a foreign war. With this conclusion drawn, we assume that we will become entangled in the next war. We, due to racial and linguistic likenesses, would align ourselves to Great Britain. Great Britain’s alliance with France ia a generally accepted fact . Now the most important and, disastrous as I see it, would be Russia’s inevitable junction with France, which is already showing decided…Couldn’t we be a little more consistent one way or the other?”

“There are innumerable other points that could be brought up for discussion, but they all point to one solution to all world affairs in regard to the United States. (1) It is this: maintain an adequate army and navy as determined by Army and Navy officials. (2) Keep this army and navy in home waters always for our defense and not aggression or the means of producing another “Grave international incident.” (3) Keep out of foreign treaties, alliances, or agreements. (4) Make a referendum of the people mandatory in declaring war. These points, and these alone, will make us a nation at peace with happy, interested people striving for more knowledge of lifesaving methods and of culture, instead of new and improved methods of warfare. Think it over!”

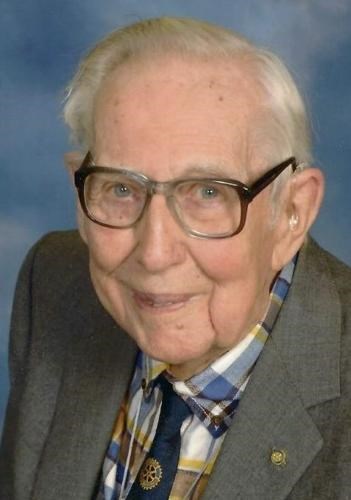

All four of these cards were authored (and signed) by Bob Shoemaker, Jr. of Anderson, IN. Robert W. Shoemaker, Jr. (1921-2022) Bob was born in New Philadelphia, Ohio, the only child of Robert W. Shoemaker, Sr. (1898-1968) and Irene English Shoemaker (1900-1988). The family moved to Anderson in 1935. Shortly after settling in Indiana, Bob became a Boy Scout. While attending the 1937 National Boy Scout Jamboree in Washington DC, Bob received his Eagle Scout award. It is likely that the seeds of this essay were planted when he sailed to Europe to participate in the 1937 World Jamboree in the Netherlands. Here, young Bobby Shoemaker witnessed the changes taking place in Hitler’s Germany firsthand. After graduating from Anderson High School in 1939, Bob enrolled in Harvard College and was on course to graduate with the Class of 1943 when the war came calling. Among Bob’s hobbies and interests were amateur radio, reading, history, and photography. Through slides, home movies, and videos, Bob compiled a remarkable visual history of his life and the life of his family from the 1920s to the current century. His many slides and movies taken during the 1937 Jamboree trips provide a fascinating glimpse of life in Washington DC, and Europe before the tragic onset of World War II. It was that love of photography that drew Bob to that Leica Exhibit at the Hotel Lincoln in Indianapolis back in 1938.

Bob was commissioned as an ensign in the U.S. Naval Reserve in 1942 and attended officers’ training programs in the Bronx, NY, and Washington, D.C, before being assigned to the Naval Mine Warfare Test Station at Solomons Island, MD, where he served as Naval personnel officer. After requesting a shipboard assignment, Bob was transferred to the Pacific for duty aboard the escort aircraft carrier U.S.S. Corregidor (CVE-58) as Lieutenant Junior Grade and Signal Officer until the ship’s decommissioning after the war in 1946. After World War II, Bob earned two graduate degrees from Harvard: an MBA and a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Government in 1947. Upon his return to Anderson in 1947, Bob remained active in the U.S. Naval Reserve Division 9-31. In 1949, Bob and his parents purchased Short Printing, Inc., then located on 20th Street near Fairview Street in Anderson. He successfully operated the business as President for almost five decades, which included building a larger one on Madison Avenue in 1961 and changing the name to Business Printing, Inc. He retired and sold the business in 2000. Bob was a Scoutmaster and Skipper of a Sea Scout ship in Anderson. He also held a variety of district and council leadership positions in Scouting for many years.

In 1946, Bob obtained his amateur radio license, and in 1952, he was asked to organize amateur radio communications for the Madison County Civil Defense, which led to his appointment as County Civil Defense Director, a position he held for 12 years. This period witnessed rising tensions with the Soviet Union and the threat of nuclear attacks, including the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. As CD Director, Bob gave many educational slide presentations regarding proper preparations in the face of nuclear threats, oversaw the selection and stocking of emergency fallout shelters throughout the county, and helped organize the conversion of the old Lindbergh School north of town into a CD emergency command headquarters. His slide show included photos taken in his capacity as an official observer at the Yucca Flats, Nevada, nuclear test in 1955. Later, Bob was invited by NASA to Cape Canaveral to observe the launch of Apollo 8, which carried astronauts into orbit around the moon for the first time, and the Apollo 15 moon mission launch. As a seven-decade member and officer of the Rotary Club, Bob secured NASA astronaut Al Worden, command module pilot for Apollo 15 and one of 24 people to have flown to the Moon, as a special speaker for the Madison County Rotary Club in 1971.

When Bob Anderson Jr.’s life is measured against that of his “peer,” Arsenal Tech grad Charles Soltau, it is easy to see that while both shared the same isolationist mentality as young men, one chose to follow that Nazi ideology of Adolf Hitler and the other followed that of Uncle Sam. Soltau faded into the obscurity that Gnaw Bone, Indiana, maintains to this day. Anderson became a public-spirited pillar of Madison County society whose shadow is still cast in that community — proving that idealogy comes and goes with the flow of generations. What often sounds like an attractive idea can easily morph into an unexpectedly bad outcome. Mark Twain is often quoted as having said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes,” and, if so, it applies today.

I will be talking about this series of articles with Nelson Price on his radio show “Hoosier History Live” this Saturday June 21, 2025 noon to 1 (ET) on WICR 88.7 fm, or stream on phone at WICR HD1. See the link below.

Original publish date May 15, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/05/15/foul-ball/

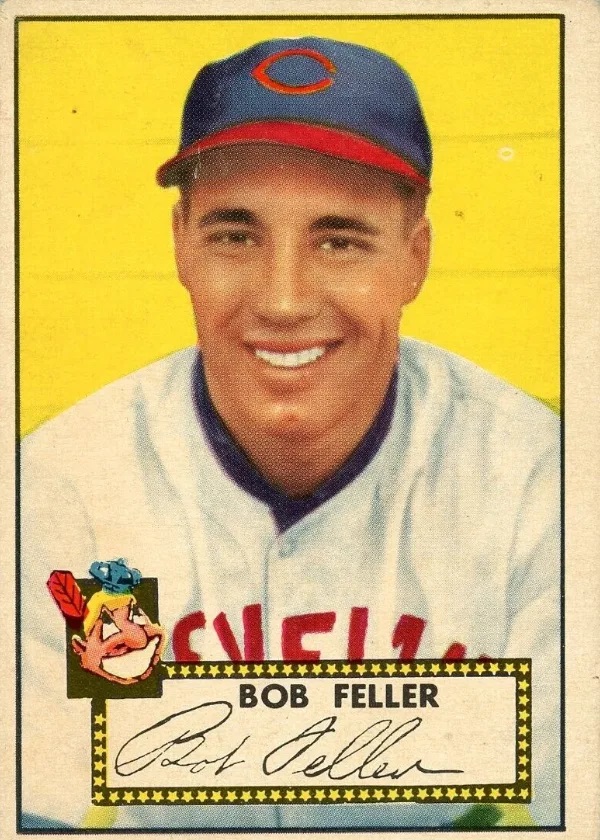

Last week, I ran a story about Cleveland Indians phenom Bob Feller’s pitched foul ball that hit and injured his mother during a game against the White Sox at old Comiskey Park in Chicago. That got me thinking about other foul ball stories and legends I’d heard about. Growing up, I spent a lot of time at old Bush Stadium on 16th Street in Indy. My dad, Robert Eugene Hunter, a 1954 Arsenal Tech grad, had worked there as a kid selling Cracker Jack/popcorn in the stands during the Victory Field years. He recalled with pleasure seeing Babe Ruth in person there and could name his favorites from those great Pittsburgh Pirates farm club teams from the late 1940s/early 1950s. I can’t tell you how many RCA Nights at Bush Stadium he took me to back in the 1970s during the team’s affiliation with the Cincinnati Reds Big Red Machine. During those outings, nothing was more exciting than chasing foul balls.

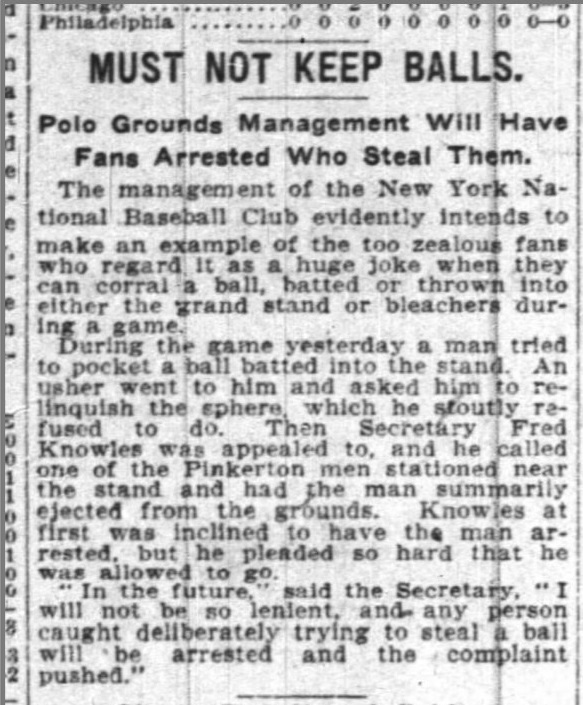

Not all foul balls are fun adventures, though; some are crazy, and others are just plain scary. Growing up, I loved reading about the exploits of those players who played before World War I. Back in those days, baseballs were considered team property and quite expensive. Fans were expected to return any ball hit into the stands (including homeruns), and balls hit out of the stadium were meticulously retrieved. In 1901, the National League rules committee, as a way of cutting costs, suggested fining batters for excessively fouling off pitches. Beginning in 1904, per a newly created league rule, teams posted employees in the stands whose sole job was to retrieve foul balls caught by the fans. Fans had a keen sense of humor, though, and they would often hide them from the “goons” or frustrate the hapless employees by throwing them from row to row. Sometimes, the games of keep-away in the stands were more fun to watch than the ones on the field. But those early WWI stories mostly involved the exploits of the players, not the fans. There were some characters in the league back then. Some of them are long forgotten and some made the Baseball Hall of Fame.

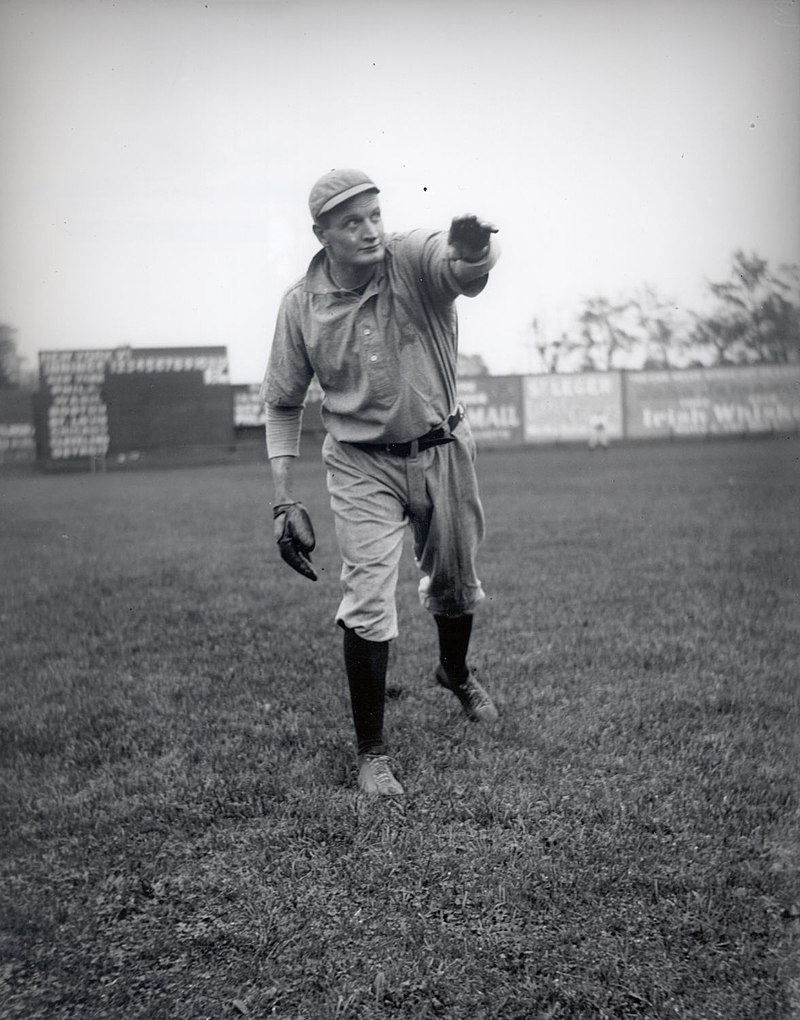

One of my favorite players from that hardball era was a square-jawed eccentric left-handed pitcher from the oil town of Bradford, Pa. named George Edward “Rube” Waddell (1876-1914). Rube played for 5 teams in 13 years. His lifetime 193-143 record, 2,316 strikeouts, and 2.16 ERA landed him in the Hall of Fame. And if there were a hall of fame for flakes in baseball, Rube would have been a first-ballot electee. If a plane flew above the field, Rube would stop in the middle of a game. If Rube heard the siren of a firetruck, he’d drop his glove and chase it. He once left in the middle of a game to go fishing. Opposing fans knew that Rube was easily distracted so they brought puppies to the game and held them up in the stands to throw him off. Rival teams brought puppies into the dugout for the same reason, knowing that Rube would drop his glove and run over to play with them every time. Shiny objects seemed to put Rube in a trance. His eccentric behavior led to constant battles with his managers and scuffles with bad-tempered teammates. Even though he was a standout pitcher, Rube’s foulball stories came off his bat, not out of his hand.

On August 11, 1903, the Philadelphia Athletics were visiting the Red Sox. In the seventh inning, Rube Waddell was at the plate. Waddell lifted a foul ball over the right field bleachers that landed on the roof of a Boston baked bean cannery next door. The ball rolled to a stop and became wedged in the factory’s steam whistle, which caused it to go off. It wasn’t quitting time yet, but the workers abandoned their posts, thinking it was an emergency. The employee exodus caused a giant caldron full of beans to boil over and explode. Suddenly, the ballpark was showered by scalding hot beans. Nine days before, on August 2, another foul ball off the bat of Waddell hit a spectator, supposedly igniting a box of matches in the fan’s pocket and ultimately setting the poor guy’s suit on fire and causing an uproar.

Waddell’s 1903 E107 Card.

Still, a foul ball hit by the aptly named George Burns of the Tigers in 1915 is worth mentioning in the same breath. His “scorching” foul liner struck an unlucky fan in the area of his chest pocket, where he was carrying a box of matches. The ball ignited the matches, and a soda vendor had to come to the rescue, dousing the flaming fan with bubbly to put out the fire.

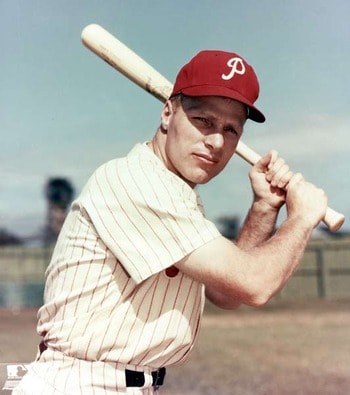

Richie Ashburn figures in many of the best foul ball stories in baseball lore. A contact hitter, Ashburn had the ability to foul off many consecutive pitches till he found one he liked. On one occasion, he fouled off fourteen consecutive pitches against Corky Valentine of the Reds. Another time, he victimized Sal “The Barber” Maglie for “18 or 19″ fouls in one at-bat. ”After a while,” said Ashburn, “he just started laughing. That was the only time I ever saw Maglie laugh on a baseball field.” Ashburn’s bat control was such that one day he asked teammates to pinpoint a particularly offensive heckler seated five or six rows back. The next time up, Ashburn nailed the fan in the chest. On another occasion, Ashburn unintentionally injured a female fan who was the wife of a Philadelphia newspaper sports editor. Play stopped as she was given medical aid. Action resumed as the stretcher wheeled her down the main concourse, and, unbelievably, Ashburn’s next foul hit her again. Thankfully, she escaped with minor injuries.

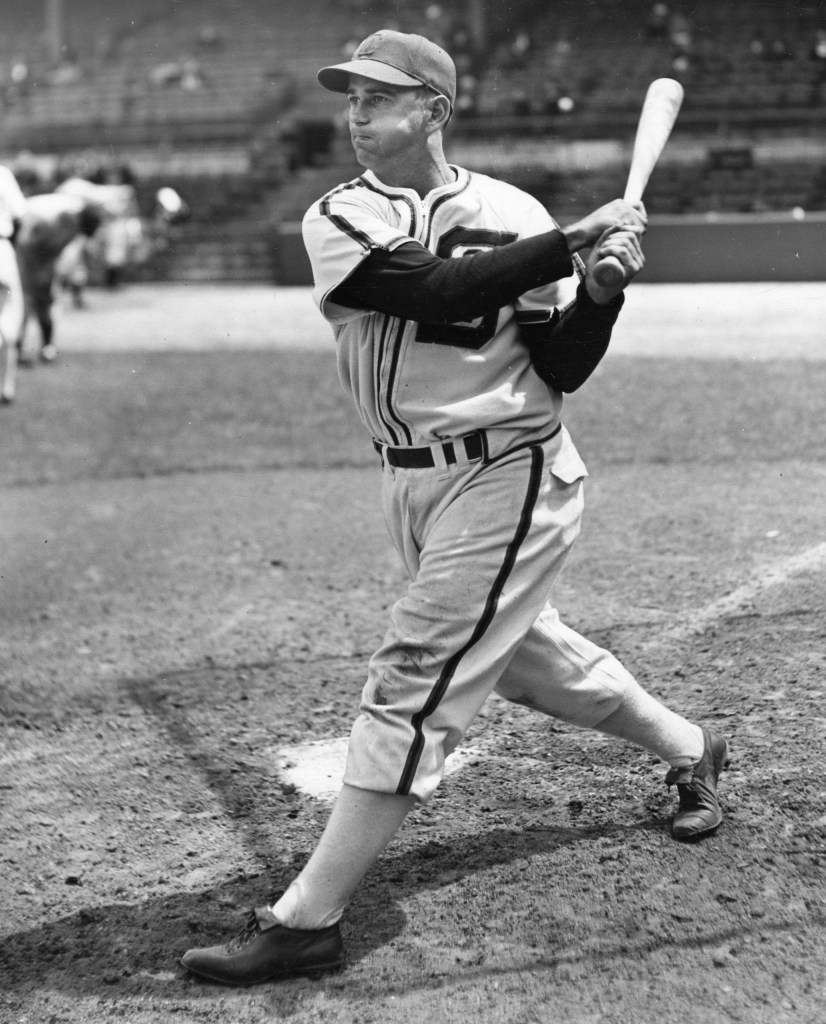

Another notable foul ball hitter was Luke Appling, the Hall of Fame shortstop with a career batting average of .310. As the story goes, Appling once asked White Sox management for a couple of dozen baseballs, so he could autograph them and donate them to charity. Management balked, citing a cost of several dollars per baseball. Appling bought the balls from his team, then went out that day and fouled off a couple dozen balls, after which he tipped his hat toward the owner’s box. He never had to pay for charity balls again, the legend goes.

Another great foul ball story involves Pepper Martin and Joe Medwick of the St. Louis Cardinals famous Gas House Gang teams of the mid-1930s. With Martin at bat, Medwick took off from first base, intending to take third on the hit-and-run. Martin fouled the ball into the stands, and Reds catcher Gilly Campbell reflexively reached back to home plate umpire Ziggy Sears for a new ball. Then, just for fun, Campbell launched the ball down to third, where Sears, forgetting that a foul had just been hit and that he had given Campbell a new ball, called Medwick out. The Cardinals were furious, but not wanting to admit his error, Sears refused to reverse his call, and Medwick was thrown out-on a foul ball!

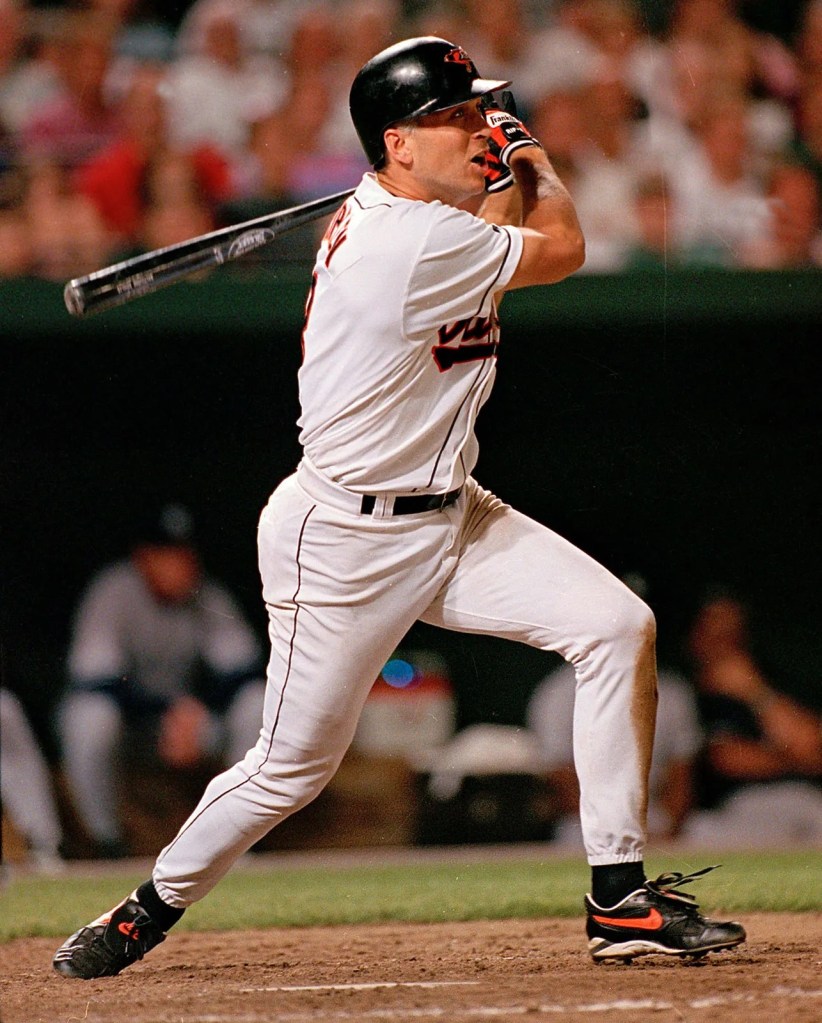

The great Cal Ripken Jr. made life imitate art with a foul ball in 1998. In the movie The Natural, Roy Hobbs lofts a foul ball at sportswriter Max Mercy, as Mercy sits in the stands drawing a critical cartoon of the slumping Hobbs. Baltimore Sun columnist Ken Rosenthal faced a similar wrath of the baseball gods after he wrote a column in 1998 suggesting that it might be time for Ripken to voluntarily end his streak, at that point several hundred games beyond Lou Gehrig’s old record, for the good of the team. Ripken responded by hitting a foul ball into the press box, which smashed Rosenthal’s laptop computer, ending its career. When told of his foul ball’s trajectory, Ripken responded with one word: “Sweet.”

Another sweet story involves a father and son combination. In 1999, Bill Donovan was watching his son Todd play center field for the Idaho Falls Braves of the Pioneer League. Todd made a nice diving catch and threw the ball back into the second baseman, who returned it to the pitcher. On the next pitch, a foul ball sailed into the outstretched hands of the elder Donovan. “I was like a kid when I caught it,” said the proud papa. “It made me wonder when was the last time that a father and son caught the same ball on consecutive pitches.”

One day in 1921, New York Giants fan Reuben Berman had the good fortune to catch a foul ball, or so he thought. When the ushers arrived moments later to retrieve the ball, Reuben refused to give it up, instead tossing it several rows back to another group of fans. The angered usher removed Berman from his seat, took him to the Giants’ offices, and verbally chastised him before depositing him in the street outside the Polo Grounds. An angry and humiliated Berman sued the Giants for mental and physical distress and won, leading the Giants, and eventually other teams, to change their policy of demanding foul balls be returned. The decision has come to be known as “Reuben’s Rule.”

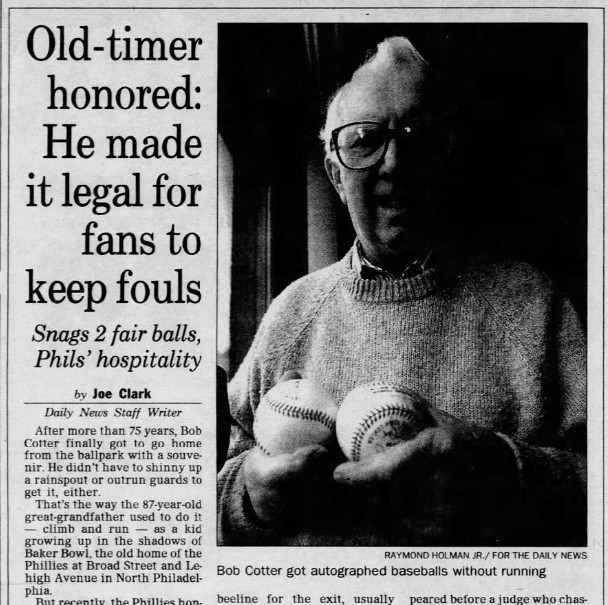

While Berman’s case was influential, the influence had not spread as far as Philadelphia by 1922, when 11-year-old fan Robert Cotter was nabbed by security guards after refusing to return a foul ball at a Phillies game. The guards turned him over to police, who put the little tyke in jail overnight. When he faced a judge the next day, young Cotter was granted his freedom, the judge ruling, “Such an act on the part of a boy is merely proof that he is following his most natural impulses. It is a thing I would do myself.” The tide eventually changed for good, and the practice of fans keeping foul balls became entrenched. World War II was another time when patriotic fans and owners worked together to funnel the fouls off to servicemen. A ball in the Hall of Fame’s collection is even stamped “From a Polo Grounds Baseball Fan,” one of the more than 80,000 pieces of baseball equipment donated to the war effort by baseball by June 1942.

One of those baseballs may well have been involved in one of the strangest of all foul ball stories. In a military communique datelined “somewhere in the South Pacific,” the story is told of a foul ball hit by Marine Private First Class George Benson Jr., which eventually traveled 15 miles. Benson’s batting practice foul looped up about 40 feet in the air, where it smashed through the windshield of a landing plane. The ball hit the pilot in the face, fracturing his jaw and knocking him unconscious. A passenger, Marine Corporal Robert J. Holm, muttering a prayer, pulled back on the throttle and prevented the plane from crashing, though he had never flown before. The pilot recovered momentarily and brought the plane to a landing at the next airstrip, 15 miles away.

In 1996, at the age of 71, former President Jimmy Carter made a barehanded catch of a foul ball hit by San Diego’s Ken Caminiti, while attending a Braves game. “He showed good hands,” said Braves catcher Javy Lopez.

With foul balls by this time an undeniable right for fans at the ballpark, what are your actual chances of catching a foul ball at a game? Well, to start with, the average baseball is in play for six pitches these days, which makes it sound as though there will be many chances to catch a foul ball in each game. While comprehensive statistics are not available, various newspapers have sponsored studies which, uncannily, seem quite often to come down to 22 or 23 fouls into the stands per game.

That seems like a healthy number until you look at average major league attendance at games. In the year 2000, the average game was attended by 29,938 fans. With 23 fouls per game, that works out to a 1 in 1,302 chance of catching a foul ball. With numbers like that, no wonder it feels so special to catch a foul ball. Nevertheless, those who yearn to catch a foul ball can improve their chances. I have listed some tips to help you bring home that elusive foul ball. Good luck!

Part I

https://weeklyview.net/2025/03/13/nazis-at-arsenal-tech-what-part-1/

Original publish date March 13, 2025.

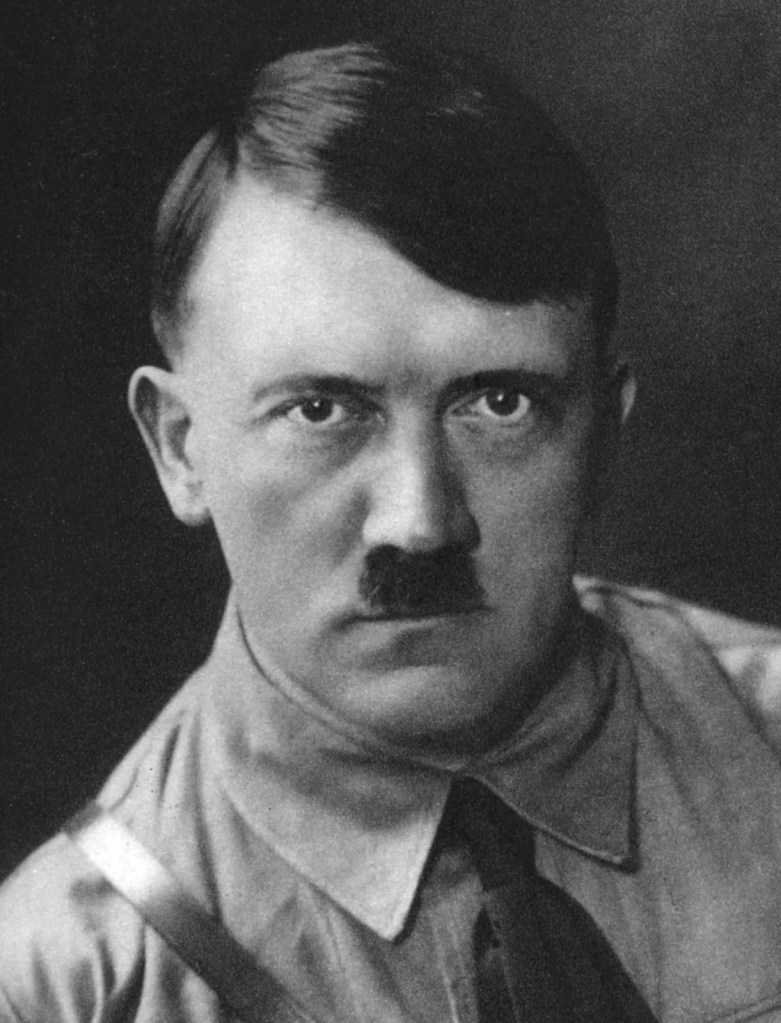

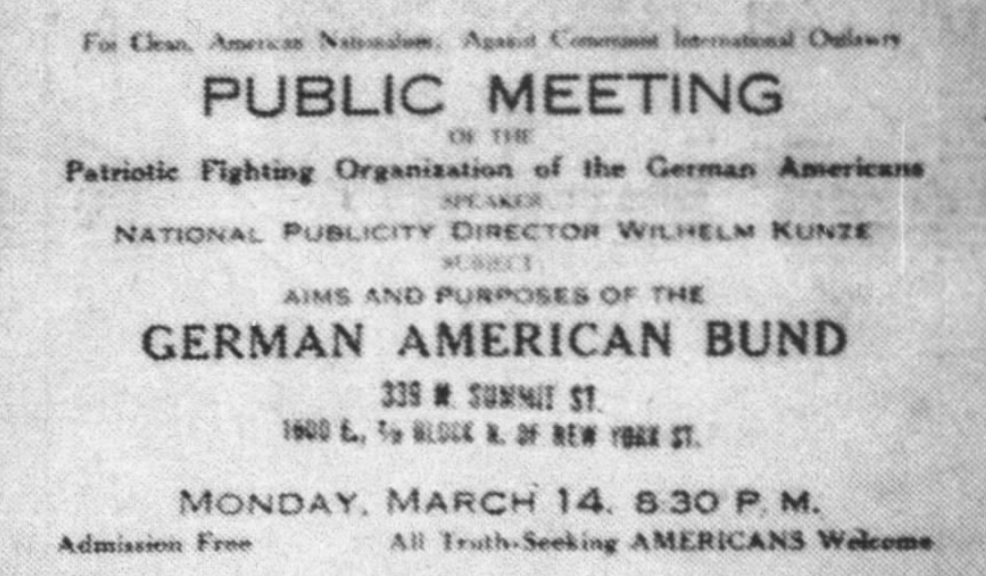

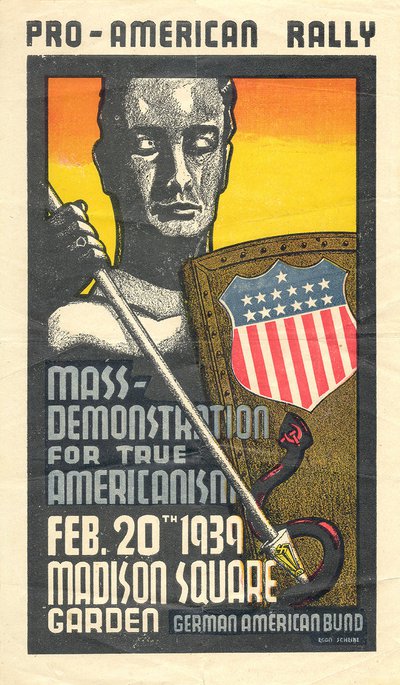

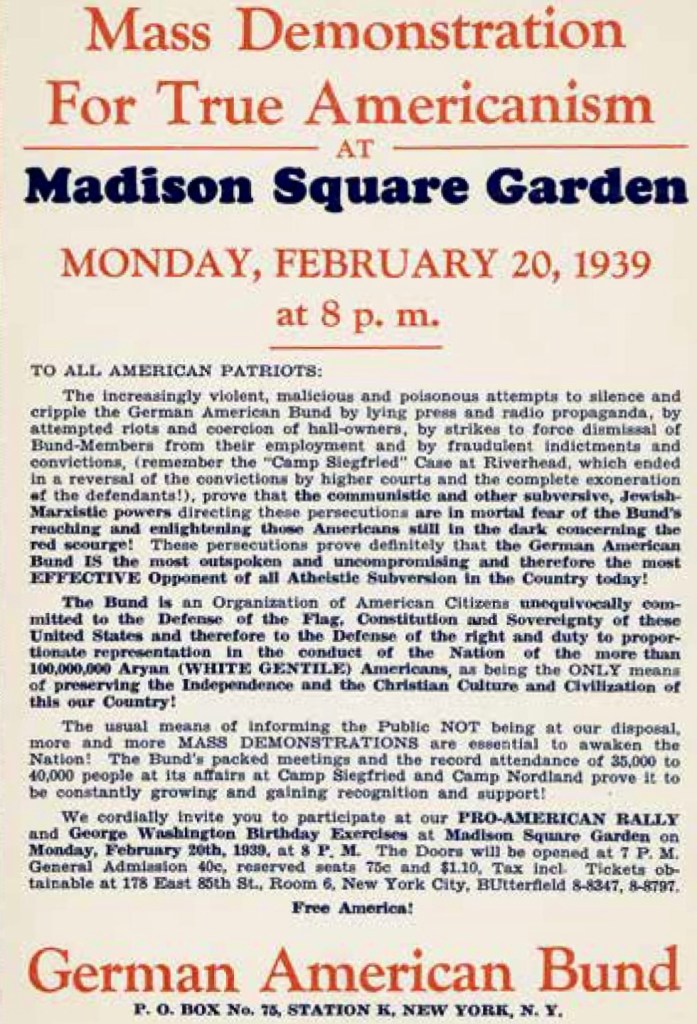

It’s true. In the years leading up to World War II, there was at least one eastside Indianapolis family openly identifying with the American Nazi Party. And three of those proud young Nazis graduated from Arsenal Technical High School. It all came to a head 87 years ago this Saturday when the Soltau home on North Summitt Street (where the La Parada Mexican restaurant now stands) came under attack by an angry mob of Circle City citizens seeking to enact their own “Night of Broken Glass” on March 15, 1938, seven months before Adolph Hitler’s Kristallnacht in Berlin, Germany in November of that same year. In March of 1938, Indianapolis newspapers were dominated by reports of German Wehrmarcht invaders poised at the gate, prepared to annex Austria into a “greater German Reich” and threatening the entire Western European theatre. Those same front pages reported on an organization of Hoosier ethnic Germans who were resolutely pro-Nazi, vehemently anti-Communist, deeply anti-Semitic, and staunchly American isolationists. In 1938, an estimated 25,000 Americans were members of this German American Bund. Indianapolis boosters hoped to swell that number by appealing to the large German immigrant community by advocating “clean American nationalism against Communist international outlawry.”

However, the German-American Bund secured very few Hoosier followers and gained little sympathy for their cause. Indiana had a well-deserved reputation for xenophobia and white nationalism that is most clearly reflected in the Ku Klux Klan’s ascent to power just over a decade before. The number of Hoosiers in league with the German-American Bund was certainly much smaller than the number of members of the 1920s KKK. Still it was committed to many of the same ideological issues as the Klan. Its history confirms the complex range of xenophobic sentiments simmering in the 20th-century Circle City.

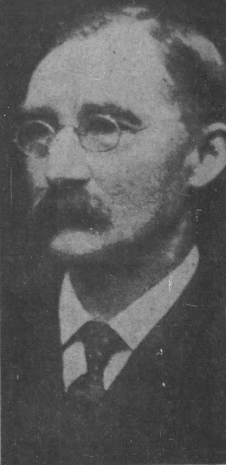

The Soltau family was closely associated with Indianapolis, particularly the east side and Irvington. John Albert Soltau (1847-1938) was a German immigrant who founded the first grocery chain in Indianapolis, the Minnesota Grocery Company. Soltau arrived here in 1873 at the age of 10. After marrying Miss Elizabeth Koehler (1851-1920), Soltau opened the first of what would become a chain of twelve grocery stores at 208 North Davidson Street. The couple had five children: William, Edward, James, John, and Benjamin. The elder Soltau remained in the grocery business for over fifty years. Three of his sons joined him, managing stores of their own. Mr. Soltau was a member of the First Evangelical Church near Lockerbie Square (where New York crosses East Street). The family residence was located at 837 Middle Drive in Woodruff Place.

In 1894, John was a Republican Ward delegate in Indianapolis. In 1902, he was an unsuccessful candidate for Marion County Recorder on the Prohibition ticket, and in 1916, he was a delegate to the national Prohibition Party convention. His long adherence to the temperance cause smacks of social conservativism, but offers no clear evidence for why his family embraced the Nazi ideology. Hoosier Prohibitionists allied themselves with the Klan’s cause in the 1920s, and in 1923, John’s brother James Garfield Soltau (1881-1932) was identified as one of the first 12,208 Ku Klux Klan members in Indianapolis. John died of “uremia and carcinoma of the prostate” on July 18, 1938, and is buried alongside his wife, Elizabeth, at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

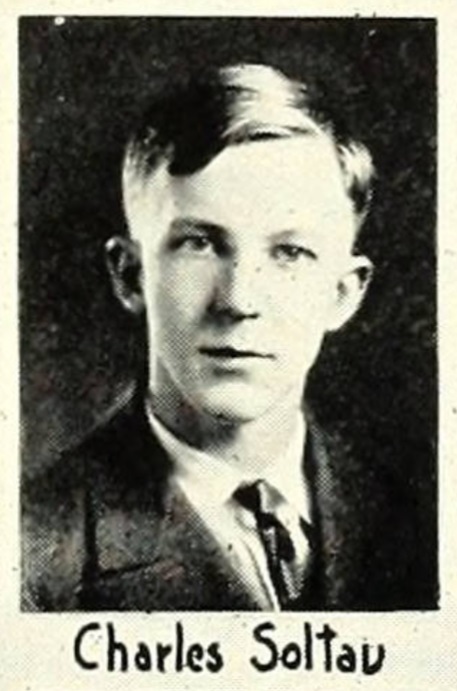

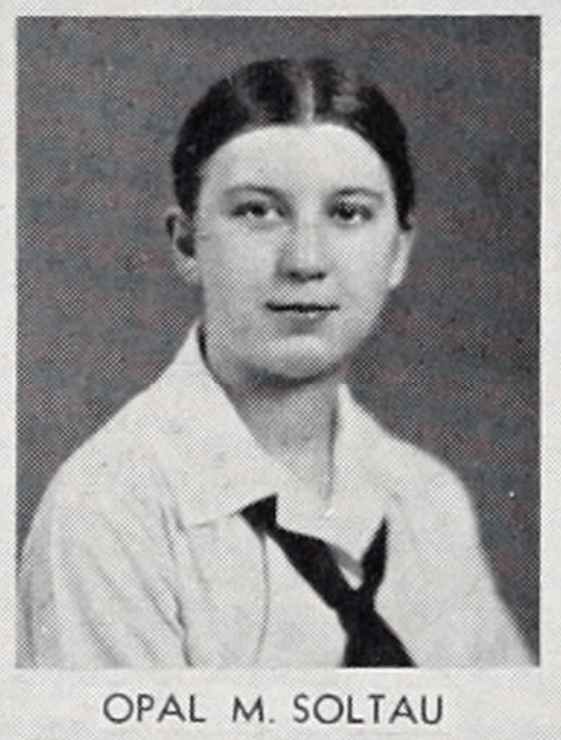

John’s eldest son, William Soltau, was a realtor who operated his agency in room 202 of the Inland Building at 160 East Market Street in the city for a quarter century. William and his wife Laura E. (Hansing) Soltau (1879-1943) were the parents of three children: Pearl Brilliance Soltau (1905-1968), Charles William Soltau (1909-1971), and Opal Margaret Soltau (1920-2008). All three children graduated from Arsenal Technical High School, Pearl, in 1922, Charles in 1926, and Opal in 1938. Pearl graduated from Butler University in 1925, Charles from Purdue in 1931 (with honors and a perfect 6.5 GPA), and Opal attended Butler University until at least 1940. The Soltau’s moved to 339 North Summit Street in 1916 and while the Soltau family was residing under that roof, it appears that all five were emersed in and sympathetic to the Nazi cause.

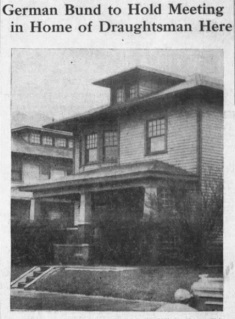

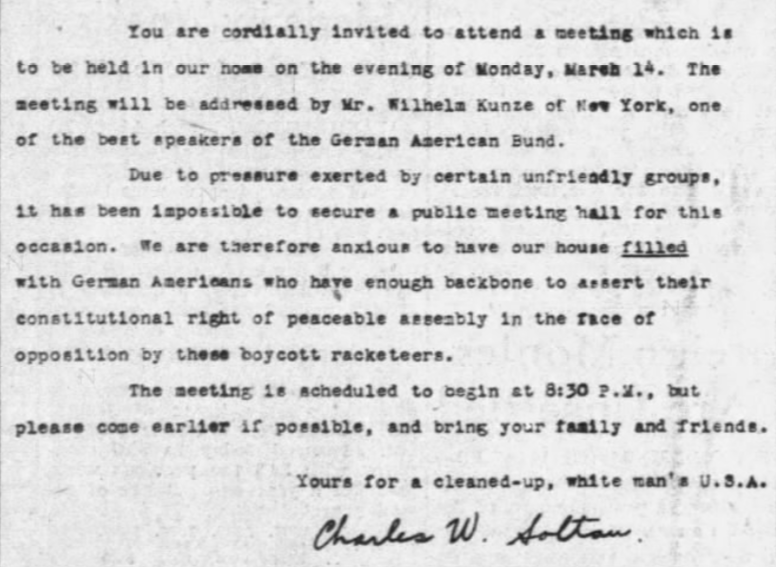

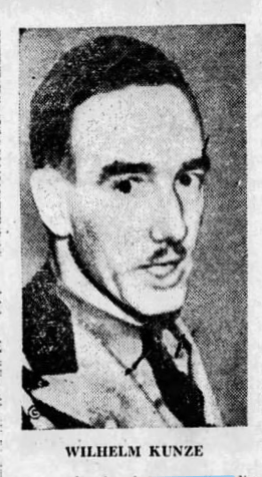

The front page of the March 9, 1938, Indianapolis News ran a photo of the Soltau House with a notice that a meeting of the German American Bund, described as a “Patriotic Fighting Organization of the German Americans”, was to be held there. Regardless, the Soltau family denied that a meeting was to be held in their home. The next day, the news ran a copy of the invitation with the address of the home and the announcement that Wilhelm Kunze, National Publicity Director of the Bund, would be the speaker and that admission was free and open to the public, especially to “All Truth-Seeking Americans”. Again, the family denied that Kunze was in the city at all, let alone scheduled to appear at the house. Kunze was fresh off his January 1938 appearance in a March of Time newsreel that the Library of Congress called “the first commercially released anti-Nazi American motion picture.” The News article announced the meeting’s date as Monday, March 14, at 8:30 pm.

Hoosiers were shocked. After all, in February, the Athenaeum, the Liederkranz Hall (1417 E. Washington St.), and the Syrian-American Brotherhood Hall (2245 East Riverside) had all canceled the Bund’s reservation and refused to host the event. On February 25th the Indianapolis Star identified “an American-born Nazi agent…born in Indiana” attempted to secure a venue “to organize Brown Shirt Nazi units in Indianapolis.” That local organizer was revealed as Charles W. Soltau from the near-Eastside. Charles wrote a letter to the Star complaining that “the German-American Bund has been accused, maligned and condemned without a trial” and suggested that the Bund’s right to meet had been undermined by “Jewish business interests”, arguing that “a certain powerful minority group, which seems to have gained almost complete control of the press, fears the effect of public enlightment.(sic)” Charles further declared that the Soltau family was “anxious to have our house filled with German-Americans who have enough backbone to assert their constitutional right of peaceable assembly in the face of opposition by these boycott racketeers.” He closed his letter as “Yours for a cleaned-up, white man’s U.S.A. Charles Soltau.” Shortly after that revelation, 27-year-old Soltau announced that the meeting was called off.

The front page of the March 15, 1938, Indianapolis Star reported, “Rocks hurled through the windows at the home of William A. Soltau, 339 North Summit Street, broke up an organization meeting of the Indianapolis affiliate of the Nazi Amerika Deutschen Volksbundes (German American bund) late last night.” William Albert Soltau (1875-1950) called the police for help after it was learned that Gerhard Wilhelm “Fritz” Kunze (1882-1958) and a small entourage had joined the Soltau family for dinner earlier that evening. Fritz Kuhn, often referred to as the “American Führer”, was the leader of the fledgling German-American Bund (Federation). Fearing for his dinner guests’ safety, Soltau asked police to escort Kunze and his guests to safety. Although Kunze refused to divulge his identity to any of the officers present, his “tooth-brush mustache”, proper Sturmabteilung brownshirt, and swastika tie-clasp made the physical connection to German Chancellor Adolph Hitler unmistakable.

When escorted from the home, Kunze declared to the officers and crowd gathered on the sidewalk, “I am a guest of Mr. Soltau, and he does not want my name known.” Kunze eventually admitted his identity to the police after they discovered the Bund application blanks Kunze held in his hands, wrapped up in a newspaper. An Indianapolis News article claimed that visible through the broken windows were, “Fifteen chairs had been arranged around a dining room table, and on it were application blanks for Bund membership.” The article noted that the “photographer for the Associated Press was ordered off the Soltau property by a man who carried a gun.” Soltau repeated his denials that a Bund meeting had been held in his home, claiming it was just “a few guests in for dinner.” The shades of the house were drawn, and a police squad car remained in front of the house from dusk to 10:30 pm when the officers went off duty. At 10:43 pm, a barrage of rocks crashed through the north windows of the Soltau house. Cars buzzed Summit Street for days afterward as curious motorists drove past the Soltau home and a near-constant gang of 40 or 50 youngsters “milled in the neighborhood”. Further exacerbating the situation, on July 18, 1938, just 4 months after the attack at his son’s home, family patriarch and Indianapolis grocery chain magnate John Albert Soltau died at age 90. Over the years, the elder Soltau and his son had purchased 4 tracts of land totaling 234 acres along State Road 46 in Gnaw Bone, 8 miles east of Nashville in Brown County. Newspapers speculated that the land was to be used as a Bund camp for Nazi activities, but the Soltau’s denied it.

Next Week: Part II: Nazi’s at Arsenal Tech…What?

Nazi’s at Arsenal Tech…What?

Part II

https://weeklyview.net/2025/03/20/nazis-at-arsenal-tech-what-part-2/

Original publish date March 20, 2025.

On March 15, 1938, an eastside Indianapolis house was rocked (quite literally) by an angry crowd after the city learned about a formational meeting of the German-American Bund, an organization formed to follow the ideals and edicts of Adolph Hitler’s Nazi party. The Soltau family, who lived at 339 North Summit Street, welcomed a controversial visitor to their home, a German transplant named Fritz Kunze. The Nazi’s visit was greeted by Circle-City residents hurling rocks through the front windows of the Soltau home. Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze was the Bund’s publicity director who invented derogatory names for people (Franklin D. Rosenfeld) and programs (The Jew Deal) he disapproved of while extolling Jim Crow laws, warned against immigrants, and advocated for the Chinese Exclusion Act. Fritz warned white Americans: “You, Aryan, Nordic, and Christians…wake up” and “demand our government be returned to the people who founded it…It has always been very much American to protect the Aryan character of this nation.”

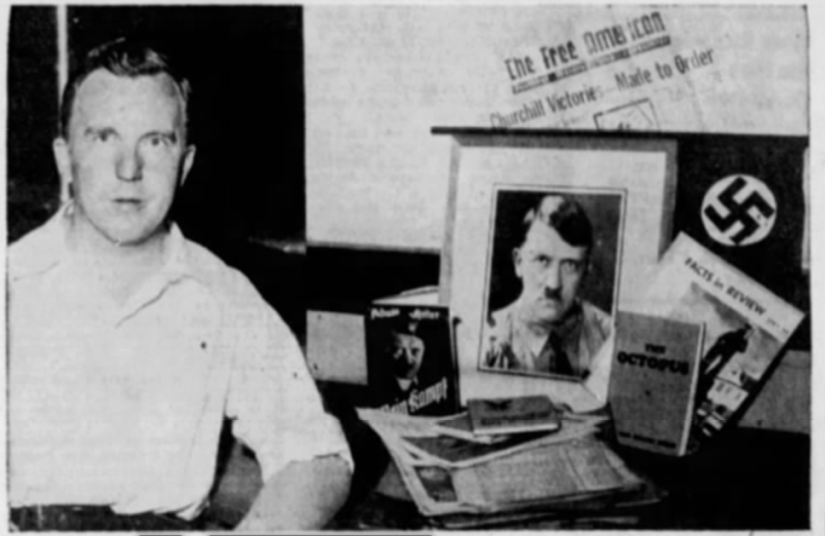

Despite the Eastside Indianapolis Nazi recruitment session debacle, the Soltau family stayed committed to Nazi ideology. In November 1938, Charles and his youngest sister, Opal, fresh off her graduation from Tech High School, returned from a Bund indoctrination trip to Germany. Some of these trips included meetings with Joseph Goebbels, Heinrich Himmler, and Hitler himself. Whether the siblings were in the Rhineland to attend a German youth camp or to enjoy a post-graduation vacation is unknown. While 18-year-old Opal fit the profile, Charles was almost 30 and may have aged out of that group. They left Hamburg on November 3rd, arriving back in New York on the 11th. The Soltau family quietly supported the Bund cause by subscribing to The Free American newsletter and other Nazi propaganda publications including a liturgy of anti-Semitic tracts like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Hitler’s Mein Kampf manifesto. A November 1941 FBI investigation identified the Soltau family as 4 of 38 stockholders in the Press (The publishing house had issued 5000 shares of preferred stock at $10 a share in 1937). The FBI noted that the Soltau family were the only stockholders from Indiana. While the Free American had local news columns in Fort Wayne and South Bend, there were none in Indianapolis.

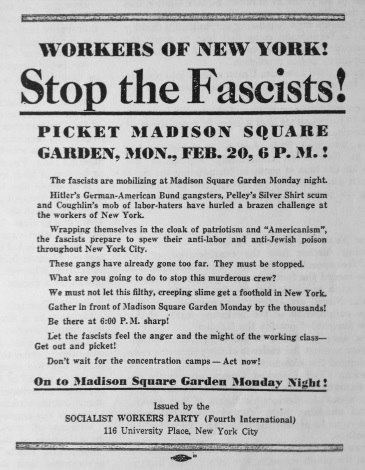

The German-American Bund was at its zenith in 1938-39, but after 20,000 people attended a Bund rally at Madison Square Garden in February 1939, New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia instigated a series of investigations that would ultimately bring them down. In September 1939, after the Nazis invaded Poland the FBI and federal government went after the Bund. Fritz Kunze was detained by the South Bend Police on May 12, 1941.

In the inventory of Kunze’s papers confiscated by the Police were cards with the names and addresses of Bund members, including the Soltau family, the only members from Indiana. Kunze was charged with espionage, and in November 1941, just a month before Pearl Harbor, he fled to Mexico, hoping to escape to Germany. Kunze was captured by the Feds in Mexico in June 1942 and sent to jail for espionage, where he spent the rest of the war. The German-American Bund disbanded officially immediately after Pearl Harbor. Regardless, some Bund members had their American citizenship revoked and were deported, while others were prosecuted for refusing to register for the draft. Kunze was eventually deported himself in 1945.

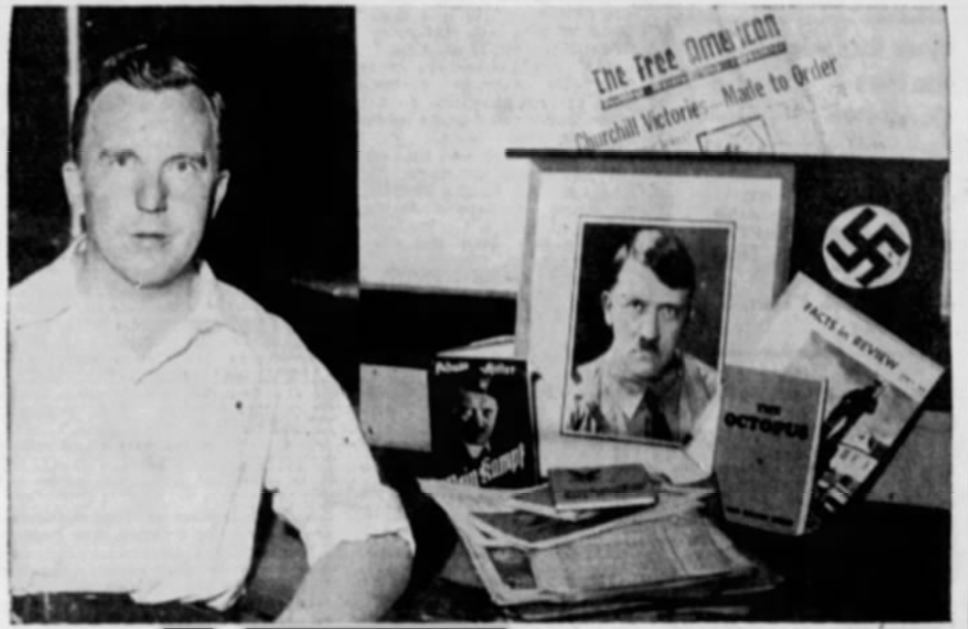

In September 1940, when the draft began, the Bund instructed its members to boycott registration, and soon, former Bundist members began to be prosecuted by the Selective Service System for failure to register. 33-year-old Hoosier Charles William Soltau was among those who refused to report for induction. In August 1942, draft dodger Soltau was arrested, and his home was raided by US Marshals who discovered a large cache of Nazi propaganda there. It included issues of The Free American, a portrait of Hitler, Swastika banners, and Nazi memorabilia. In a four-page letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Soltau argued that “in all my association with the German-American Bund I never was guilty of any subversive activity.” After spending a couple of nights in jail, Soltau posted a $5000 cash bond. When he appeared in court in November, he argued that, “My conscience will not permit me to bear arms against the German people.” He informed the court that “This war is a war of aggression by the United States against the Germans. I am a man of German blood, and I don’t think it is right or fair or just for a man of German blood to bear arms against the German people.” It took the jury six minutes to deliberate and deliver a five-year sentence to Soltau. Judge Robert C. Baltzell concluded that “I have never seen a more contemptuous fellow in this court,” and “I am going to do all I can to see that you serve as much [time] as possible.” In December 1943, while serving his sentence at the Federal Correctional Institute in Milan, Michigan federal prison, Soltau’s mother Laura died. Charles was released in 1946, and with his sisters, Opal and Pearl, he moved to their secluded Brown County property near Gnaw Bone.

Their father, William Albert Soltau, died there on October 6, 1950, at age 75. His funeral service was held at Shirley Brothers Central Chapel in Irvington, and he is buried at Memorial Park Cemetery on Washington Street alongside his brothers, whose funeral services were also held at Shirley Brothers. At least one brother, Benjamin Harrison “Ben” (1889-1963), was a member of Irvington Masonic Lodge 666, and another, James Garfield Soltau (1881-1932), was an admitted member of the KKK. The Soltau siblings quietly left Indianapolis and moved to Gnaw Bone, where they lived together in Brown County for the remainder of their lives, and none of the three ever married. The siblings started with three goats in 1952, and by 1962, their “trip” (or tribe) had reached 44 head, so they created Pleasant Valley Goat Farm on their 200-acre Gnaw Bone property. The family sold goat’s milk and yogurt in local farm markets. Pearl Soltau also moonlighted as an accountant for a local hosiery mill, preparing tax returns on the farm. After a two-year illness, Pearl died at the Gnaw Bone farm in May 1968 at the age of 62. Charles died there on July 5, 1971, at age 61. Although Charles’s membership in the “German-American National Congress” was mentioned in his obit, Pearl betrayed no history of continued xenophobic activism after the war. Both are buried at Henderson Cemetery in Gnaw Bone.

However, the youngest sibling, Opal, remained committed to neo-Nazi causes for more than a half-century after the war. Even after the deaths of her siblings, Opal continued to agitate for unpopular political causes. Opal had been a standout at Arsenal Tech High School. She was a straight-A Honor Roll Student and received the scholarship medal from the Tech faculty in 1938. In the 1980s, Opal Soltau was accused of mailing neo-Nazi propaganda from the post office in Nashville, In. In September 1996, Opal sold her parcel of 120 acres in Brown County and by January 1997, she had moved to Nebraska. That same month, she became a Director for the National Socialist German Workers’ Party-Overseas Organization. Opal Soltau died in Lincoln in August 2008 and is presumed buried there. No one knows how the pilot light of Nazi fervor was lit in the Soltau family and, for that matter, how it burned out of control within the hearts and minds of these three Arsenal Tech graduates. Political ideology grows unchecked when surrounded only by like-minded individuals living in a silo of misinformation. Sometimes, it is the better part of valor to explore divergent opinions. The flame of Nazism burns through everything it touches. Characterized by extreme nationalism and steered by blind faith in misguided authoritarianism, its victims don’t realize what has happened until it’s too late. And by then, no matter what, they will never admit that they were ever wrong in the first place.

For a more thorough study of the Soltau family, I recommend the blog Nazis in the Heartland: The German-American Bund in Indianapolis by the late Paul R. Mullins (1962-2023), Anthropology Professor at IU Indianapolis (formerly IUPUI).

Original publish date: March 1, 2018

Last Thursday a young eastsider by the name of Trevor McCoy was driving south on Oriental Avenue when he was startled by a large piece of rebar as it came knifing through the floorboard of his car. The steel bar curled towards the sky as it traveled up and out the back window before McCoy’s car came to a halt, ripping off the muffler in the process. The incident happened around midnight in front of Arsenal Technical high school. The driver was shaken, but unhurt.

The news story piqued my interest because it happened on Oriental Avenue. My dad, Robert E. Hunter, grew up on Oriental and graduated from Tech in 1954. He delighted in taking detours whenever possible to point out the stoop that was once his family home. “That’s my stoop, that’s all that’s left.” he would say. However, as I learned the details of the incident, one word popped into my mind: Snakehead!

As an imaginative, history-loving kid, snakeheads were fodder for my nightmares. A snakehead is the term used to describe iron rails which would curl up and come loose from their wooden rails. Often, snakeheads took center stage in ghoulish tales where rails would pierce the bottom of a car, crashing upwards into the wooden floorboards like a knife through butter, sometimes impaling some poor unsuspecting passenger.

Traveling through the South in 1843-44, Minnesota clergyman Henry Benjamin Whipple wrote on page 76 of his diary: “The passengers are amused on this road by running off the track, sending rails up through the bottom of the cars and other amusements of the kind calculated to make one’s hair stand on end” Likewise, in his book “Southern Railroad Man: Conductor N. J. Bell’s Recollections of the Civil War Era (Railroads in America)”, Bell wrote: “It is said that one of these snakeheads stuck up so high that it ran over the top of a wheel of a coach and through the floor, and killed a lady passenger”

As anyone who has ever taken one of my tours knows, my Grreat-grandfather was a lifetime railroad man. He spoke of snakeheads often and always in the most terrifying terms. I searched every book, magazine and newspaper I could get my hands on looking for clarification on this dread phenomenon. Let me tell ya, researching in the years before the internet wasn’t for sissies. It took me years to discover the truth behind snakeheads and it turns out, they weren’t as scary as they were made out to be. Unless you were a first generation Hoosier.

Although the engine is the undisputed king of the rails, nothing is more important to a railroad as the track. After all, without rails, ties, and ballasting, freight and passengers do not move. Even though the image of the railroad is most closely tied to the American west, the railroad was born in France in the early 1700s. Or England in the mid 1700s. Depends on which version you believe. There are even those that say it was developed in Boston in the late 1700s. Regardless, that is an argument this article will not settle. The 4-feet width and 8 1/2-inch height were reportedly based upon ancient Roman chariot roads, that much is known.

In the United States, the Granite Railway of Massachusetts is credited as the very first, opening on October 7, 1826. It used early strap-iron rails atop a wooden base with thin strips of iron added for increased strength. During that first decade, virtually everything about railroading was an experiment learned on the fly. Early on, the strap-iron method worked best and engineers eventually learned that dense hardwoods, like oak, proved the most economical material for the supporting base. It was determined that cross-ties be at least 8-10 inches thick and about 8-10 feet in length.

Snakeheads reared their ugly heads, literally, as the straps holding the flat iron rails began to wear out after a decade or more of almost constant use. While crews of laborers were employed to inspect and replace any worn straps, the mass expansion of the railroad severely taxed the time and resources of railway inspectors. Strap failures caused the rails to become dislodged and the shock and bounce of the trains caused them to curl up. One train might pass over a dislodged rail without incident, while the next might encounter an entirely different rail situation as the loose end of the rail flew up violently under spring tension. One need only think of the last time they got a splinter, then magnify it, to imagine the result.

The prospect of an iron rail ripping through the bottom of a rail car is terrifying, but it seems to be confined solely to railroads is use before the Civil War. The reason snakeheads are so hard to research is the lack of comprehensive statistics for antebellum railroads. There was no federal agency collecting data and state interest was even less. Railroad companies sometimes self-reported accidents, but they had an obvious incentive to under-report.

To determine how prevalent and dangerous snakeheads actually were, the best way is to examine contemporary reports, if you can find them. The April 7, 1841 Newport Rhode Island Republican newspaper reported an accident near Bristol, PA: “As the train of cars were going from New York towards Philadelphia, near Bristol, one of the wheels struck the end of an iron rail, which was loose, and erected in the manner generally called a snake’s head.—The bar passed through the bottom of the car, and between the legs of a passenger, (Mr. Yates, of Albany) tearing his cloak in pieces, grazing his ear, and thence passed out the top of the car. An inch difference in his position on the seat, and he must have been killed.”

On June 22, 1841, the Boston Daily Atlas reported a similar accident in New Jersey, but later retracted the story after the president of the railroad wrote that the injury was caused by the passenger falling on a “fragment of the seat,” not from a rail springing through the floor. A careful (and exhausting) internet search reveals some 20 newspaper accounts of snakeheads in antebellum era newspapers. In one, a woman was slightly injured when a piece of iron entered a car in New York around 1848, and in another, a workman was killed on a construction train of the Jersey Central some years earlier. Most injuries usually stemmed from passengers being shook up from the jolt as the train left the tracks rather than being directly injured by the rail, but some of the injuries were frightening nonetheless.

In 1845, John F. Wallis of the Virginia legislature was injured on the Winchester and Potomac Railroad. According to the Baltimore Sun on July 21: “It lifted Mr. W. completely off his seat, coursing up the surface of his leg and abdomen, lacerating him in several places and injuring his hand severely.” The New London, Connecticut, Morning News gave a more vivid description of the same accident: “One of the bars of iron becoming loosened from the rails, it shot up through the car at the seat where Mr. Wall was sitting, severely lacerating the back part of the hand, cutting his breast and pinning him up to the top of the car.”

Only one fatality could be found and that was reported in the August 22, 1843 Baltimore Sun newspaper. It happened to a “young man named Staats” killed on a train in New Jersey on the way to New York City, “the bar entered under the chin of this young man, and came out at the back of his head. He was instantly killed, but no other person injured. The cars went back to Boundbrook, left the body, and then after an hour’s delay, started for the city.” As macabre as it may sound, a description this gruesome was exactly what I needed to justify those nightmares of my youth.

While 20 snakehead reportings in a 30-year period might not qualify as a catastrophic transportation epidemic, it does make the snakehead newsworthy. These numbers do not take into account unreported snakehead incidents where no injury resulted. The vagueness of most reports and the difficulty of finding them in newspapers must be viewed as a sign of the times. Obviously, snakeheads were bad for business. However, the railroad workers knew the stories and they were quick to spin their tales to unsuspecting, impressionable laymen. That’s how folklore starts in the first place; part fact, part fiction and all imagination.

By the time of the Civil War, strap-iron rails fell out of favor, deemed too costly to maintain (and too dangerous) by the railroads. In 1831 solid iron, “T”-rail had been introduced but were not yet widely in use. By 1839, American railroads ran on tracks of a wide variety of gauges and shapes: 101 railroads were still using strap iron on sleepers, forty-two were using some form of shaped rail, and twenty-nine were using an unspecified method.

That all changed when, on October 8, 1845, the Montour Iron Works of Danville, Pa. rolled the first iron T-rails in the United States and the age of standard gauge track was born. The rail looked like a capital “T,” only inverted; the top was placed on the ground, providing a solid base of support while the narrow end was the wheel’s guideway. Within a single generation, American railroads replaced every foot of iron rail track with stronger and more durable steel T-rails. Interestingly, even today, some lightly used branch lines can still be found carrying rail rolled during the late 19th century.

That brings us back to the Arsenal Tech snakehead that appeared last week. The piece of rebar that swept up and out of the pothole to pierce young Trevor McCoy’s car has been cut off and the pothole has been filled. No doubt some of you may be wondering what a piece of rebar was doing there in the first place. Rebar (short for reinforcing bar) is used in roads to make the concrete stay in place after it cracks, not really to make the road stronger. Rebar gives tensile strength, nothing more. Pot holes are caused by tiny cracks in the concrete that allow water to seep in. The water destroys the concrete from inside the crack during the freeze / thaw cycle.

Antebellum Americans viewed the “terror” of the snakehead as a risk they were willing to accept and in time, snakeheads faded into folklore. The winter of 2017-18 saw an estimated 10,000 potholes on over 8,000 miles of city streets. By most accounts, this season’s more radical than usual freeze / thaw cycle has contributed to the worst pothole season ever. These rebar reinforced concrete streets are reaching social security eligibility age. Rebar snakeheads may well be on their way to becoming the folktales of Uber and Lyft drivers in years to come.