Tag: Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln’s First Ghost Story.

Original Publish date October 7, 2021. https://weeklyview.net/2021/10/14/abraham-lincolns-first-ghost-story/

There are many ghost stories associated with Abraham Lincoln. Most revolve around his time in the White House, his assassination at Ford’s Theatre, and his death in the Petersen House across the street. But what was the first ghost story that Abraham Lincoln ever heard? Historian Louis A. Warren, whose 1959 book “Lincoln’s Youth. Indiana Years 1816-1830” is considered to be the definitive work on Lincoln’s early life in the state, does its best to answer that question.

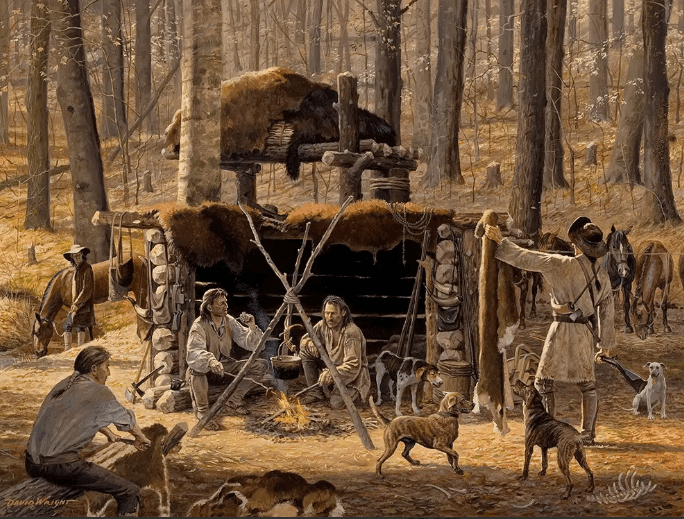

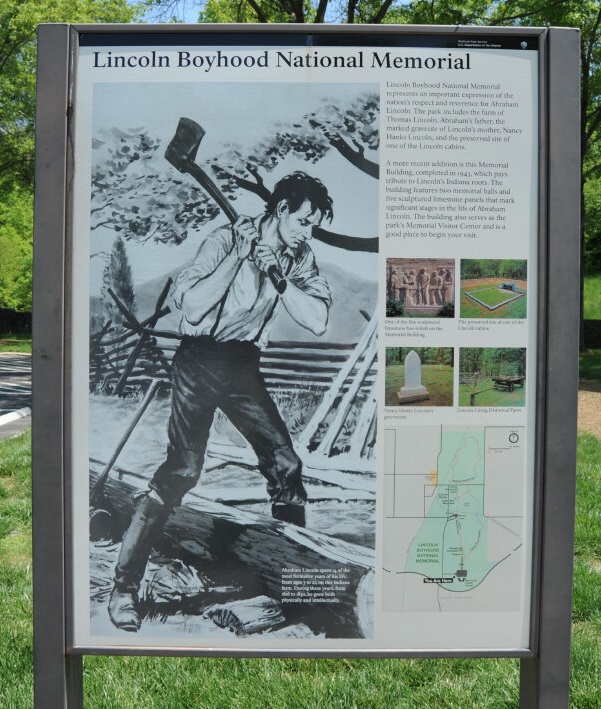

In the fall of 1816, Thomas and Nancy Lincoln packed their belongings and their two children, Sarah, 9, and Abraham, 7, and left Kentucky bound for southern Indiana. Arriving at his 160-acre claim near the Little Pigeon Creek sometime between Thanksgiving and Christmas. Thomas moved his family into a hunter’s half-face camp consisting of three rough-hewn walls and a large fourteen-foot space where a fire was almost always kept burning. Lincoln’s earliest memories of this home were the sounds of wild panthers, wolves, and coyotes howling just beyond the opening.

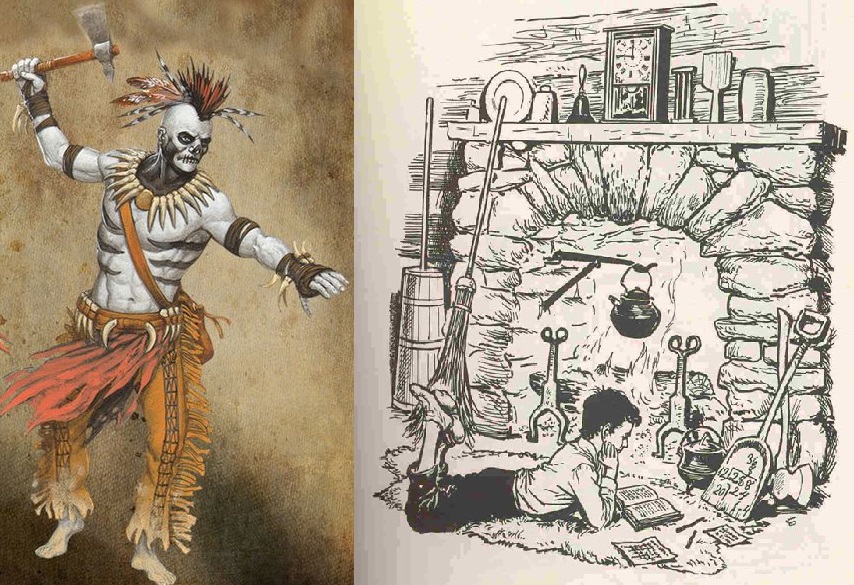

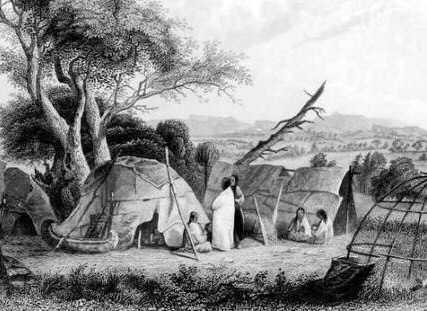

Once the chores were finished, Thomas would entertain his small family with tales of hunters, wild Indians, and ghosts. None of which was more frightening than the ghost of old Setteedown, mighty chief of the Shawnee tribe. The Shawnees were scattered throughout the region with their main settlement of about 100 wigwams located on the Ohio River near present-day Newburgh.

For the most part, the Indians were friendly and peaceful. Tradition recalls that Chief Setteedown (or Set-te-tah) and settler Athe Meeks were the exceptions to that rule. The Chief accused Meeks, a farmer and trapper, of robbing his traps and Meeks accused Setteedown of stealing his pigs. A feud developed between the two men that would ultimately leave both men dead.

The hatred became bitter and Setteedown decided to settle the matter once and for all. Early on the morning of April 14, 1812, Setteedown, his seventeen-year-old son and a warrior named Big Bones lay in wait outside the Meeks family cabin. The warriors were armed with rifles, knives, and tomahawks. When Atha, Jr. stepped out of the cabin to fetch water from a nearby spring, one of the Indians fired at him, wounding him in the knee and wrist.

In 2016, descendent Anthony Dale Meeks detailed the encounter in his family history. The Indians “crept up behind a fodder stack ten or twelve rods in front of the door and when my brother Athe (Jr.) got out of bed and passed out of the house and turned the corner with his back towards them, they all fired at him. One ball passed through his knee cap, another ball passed through his arm, about halfway from his elbow to his wrist. Another ball passed through the leg of his pants doing no injury.”

When Atha, Sr. heard the shots, he ran out of the cabin where Big Bones shot him as he exited the doorway. Margaret Meeks and another son dragged the dying man into the cabin before the Indians could scalp him. Atha, Sr. died without ever knowing what hit him. That 2016 account continues “Meanwhile father jumped out of bed, ran to the door to see what was up, and met an Indian right at the door who shot him right through the heart. He turned on his heels and tried to say something and fell dead under the edge of the bedstead.”

Setteedown and his son then ran to the wounded younger man and attacked him with their tomahawks. Meeks Jr. managed to fight his attackers off until his uncle William arrived from his adjacent cabin. William Meeks fired his rifle at the tribesmen, killing Big Bones and chasing the other two away.

Some accounts report that the attack on the Jr. Atha was more of a contest of humiliation than a duel to the death. Chief Setteedown and his son were toying with their prey like a cat with a mouse, throwing tomahawks and knives at the wounded young man from a close distance.

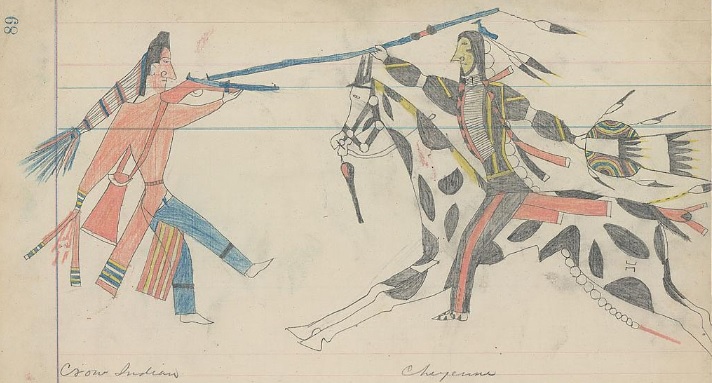

Among the Plains Indians, counting coup is the warrior tradition of winning prestige in battle by showing bravery in the face of an enemy. It involves shaming a captive with the ultimate goal being to persuade the enemy combatant to admit defeat, without having to kill him. In Native American Indian culture, any blow struck against the enemy counted as a coup. The most prestigious acts included touching an enemy warrior with a hand, bow, or coup stick and escaping unharmed; all without killing the enemy. The tradition of “counting coup”, if true in this instance, ultimately cost the great Chief his life. The gruesome practice allowed armed avengers to bring this “game” to an end by precipitating a hasty retreat.

Some eight hours later, a group of settlers arrived at Setteedown’s village seeking revenge. The vigilantes captured Setteedown, his wife, the son who participated in the attack, and two or three other children. The posse confined them in the cabin of Justice of the Peace Uriah Lamar near Grandview. They were guarded by three men, including the deceased brother William Meeks. Sometime during the night the old chief was shot and killed, presumably by Uncle William Meeks.

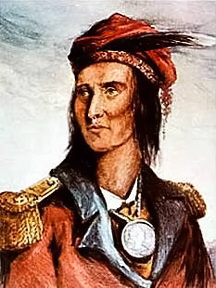

The remaining family members were banished from the region. Legend claims that they left a treasure behind buried somewhere near Cypress Creek and the Ohio River. Setteedown’s tribe disbanded and reportedly joined Tecumseh to fight in the War of 1812.

And what became of Chief Setteedown’s body? Author Louis Warren notes, “Setteedown was buried in his Indian blanket in a shallow grave close to the Lamar cabin. Mischievous boys were reported to have pushed sticks down through the soil until they pierced the old blanket. (thereby releasing his vengeful spirit) And for many years old Setteedown’s ghost was supposed to be visible at times in the vicinity.”

Local lore claims that old Chief Setteedown roamed the hills, dales, and waterways of Spencer and Warrick County looking for scalps to add to his war belt. Frontier children were warned that Setteedown’s playful spirit was a ruse with deadly intentions. Chief Setteedown was searching for souls to repopulate his lost tribe in the afterlife. In an age when children were often in charge of refilling the household water trough, gathering firewood, or collecting nuts and berries to supplement every meal, it is easy to imagine how ghost stories about bloodthirsty Indians may have sparked young Abe Lincoln’s imagination. The setteedown legend had every element that would have sparked a child’s imagination: Indians, murder and lost treasure.

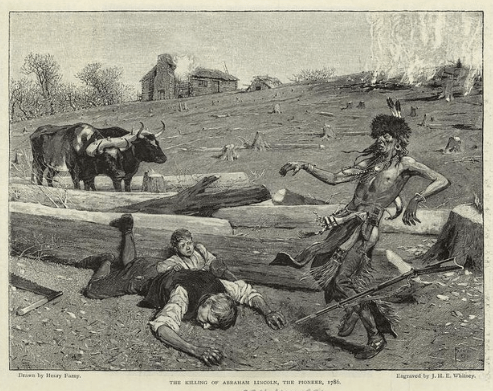

The legend takes on added significance when it is remembered that Abraham Lincoln’s namesake grandfather was ambushed and killed by Indians. In May 1786, Abraham Lincoln, Sr. (his Kentucky tombstone lists his surname alternatively as “Linkhorn”) was putting in a crop of corn with his sons, Josiah, Mordecai, and Thomas, when they were attacked by a small war party. He was killed in the initial volley. In referring to his grandfather in a letter to Jesse Lincoln in 1854, Lincoln wrote that “the story of his death by the Indians, and of Uncle Mordecai, then fourteen years old, killing one of the Indians, is the legend more strongly than all others imprinted upon my mind and memory.”

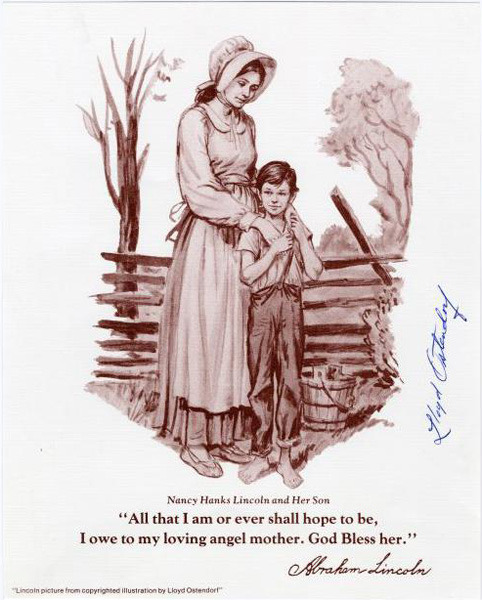

Although life was generally good for the Lincoln family during their first couple of years in Indiana, like most pioneer families they experienced their share of tragedy. In October 1818, when Abraham was nine years old, his mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, died of “milk sickness”. The milk sickness ensued after a person consumed the contaminated milk of a cow infected with the toxin from the white snakeroot plant ( or Ageratina altissima). Nancy had gone to nurse and comfort her ill neighbors and became herself a victim of the dreaded disease.

Thomas and Abraham whipsawed Hoosier Forrest logs into coffin planks, and young Abe whittled wooden pegs with his own hands, pausing only briefly to wipe the tears away that were flowing down his cheeks. Ultimately, Abe’s hand-carved pegs fastened the boards together into the coffin for his beloved mother. She was buried on a wooded hill south of the cabin. For young Abraham, it was a tragic blow. His mother had been a guiding force in his life, encouraging him to read and explore the world through books.

His feelings for her were still strong some 40 years later when he said, “All that I am or hope to be, I owe to my angel mother.” Lincoln’s fatalistic countenance, his famous bouts with melancholy, and his overall sad-faced demeanor could easily be traced back to those “growing-up” days in Southern Indiana. It is easy to imagine that, although terrifying to most children, the Setteedown ghost story was welcome entertainment to the hard reality of life on the Hoosier frontier for young Abe Lincoln.

A Gift from a Friend. Abraham Lincoln, Art Sieving, and the Long Nine Museum.

Original publish date October 3, 2024. https://weeklyview.net/2024/10/03/a-gift-from-a-friend/

Rhonda and I strolled through Irvington last week to reconnect with some old friends. We visited Ethel Winslow, my long-suffering editor at the Weekly View, and then stopped in to see Jan and Michelle at the Magick Candle. From there we went down to see Dale Harkins at the Irving and then popped into Hampton Designs to check in with Adam. After that, we tried (in vain) to track down Dawn Briggs for a stop-and-chat, then traveled over to see Randy and Terri Patee for a 3-hour porch talk over a fine cigar. Why do I retrace our visit with you? Simply because I hope that anyone reading this article either is, or will, make a similar stroll through the Irvington neighborhood this Fall season and visit their old haunts as well.

I am blessed to know these folks and every one of them has been kind, giving, and thoughtful to us over the years, particularly lately as Rhonda has faced some difficult health challenges. The gals at the Magick Candle have gifted me treasures over the years connected to the people and places they know I love (Disney’s Haunted Mansion and Abraham Lincoln come to mind), the Patees have given me relics from the pages of history, and yesterday, Adam stopped me in my tracks by stating, “Wait, Carter found something for you.” Adam fumbled around gracefully behind the counter before finding the object of his search. As he handed it to me, I felt certain that he believed it to be just another Lincoln item, but I knew immediately what it was.

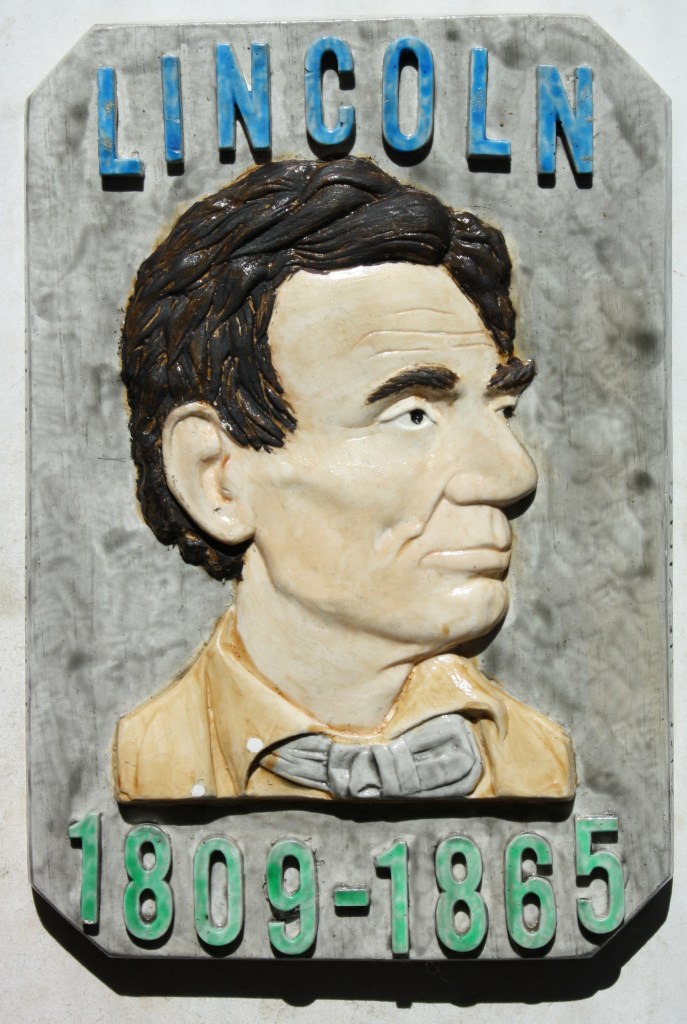

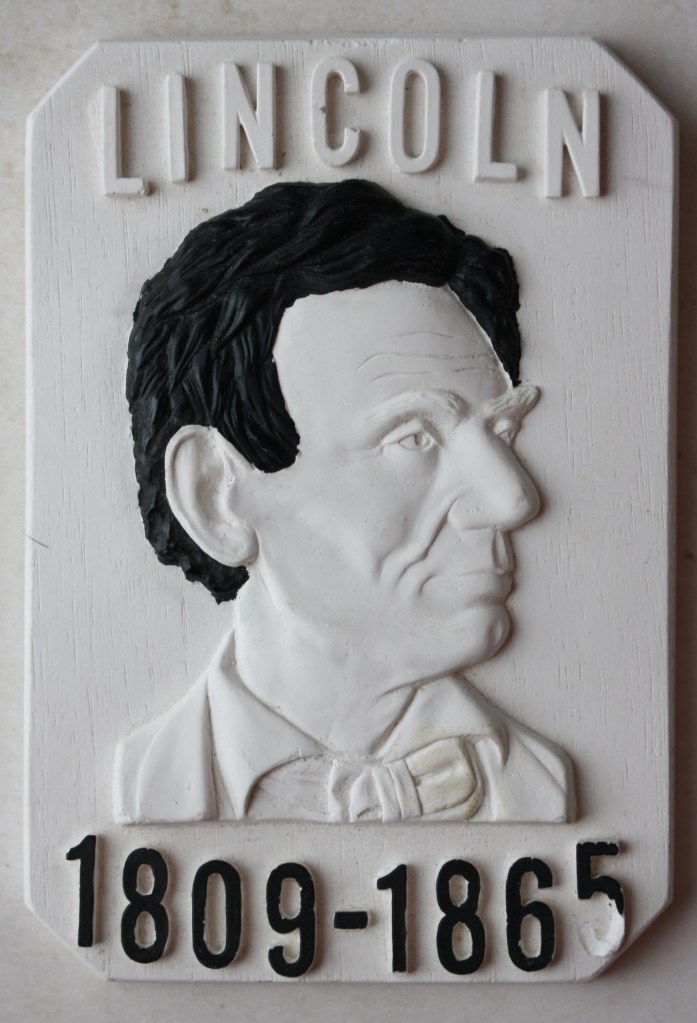

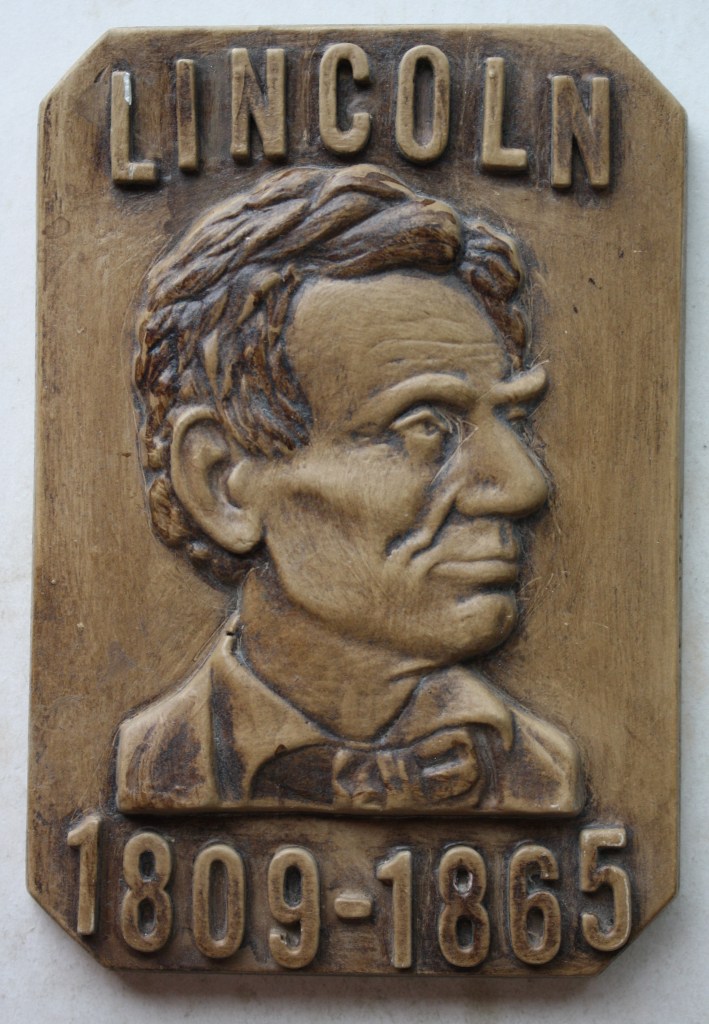

The object is a ceramic plaque about the size of a paperback novel picturing a young, beardless Abraham Lincoln with his birth and death dates inset in raised / relief lettering on the front. It is painted in bright Victorian Era colors that teeter on the edge of being gaudy but are always irresistibly attractive. Rhonda was standing by my side (as always) and when I showed it to her she oohed and aahed at it simply because she understands what such things mean to me. When I told her that it had a secret surprise attached to it, she looked closer at it. Knowing what was in store, I turned the plaque sideways in my hand to reveal the artist’s name, Art Sieving, on the right edge and then turned it over to the left edge to show the town name of Athens, Illinois. Since she has listened patiently to my historical ramblings for 35 years now, she wisely responded, “Oh, the Long Nine Museum.” Ding, ding, ding, we have a winner!

Carter and Adam had no idea, since, unlike me, they have lives outside of history books and museums, but with this gift, they had hit me in my sweet spot. I knew what it was because I already have a version, but mine, while still interesting to me, is a bland matte-finish version that pales in comparison to this one. These plaques were created by Arthur George Sieving (1902-1974) from Springfield, Ill. He was a wood carver, magician, sculptor, and ventriloquist who created many fine architectural carvings, clocks, and ventriloquist figures. At the time of his death, Art was working on the diorama displays at the Long Nine Museum in Athens. He is buried in Springfield’s Oak Ridge Cemetery final resting place of Abraham Lincoln. I was introduced, unknowingly, to Sieving’s work when, many years ago, I purchased a stunning metallic gold plaque depicting the Abraham Lincoln Tomb. About the size of a college diploma, like Carter’s plaque, it depicts the Tomb in a raised/relief style so realistically that it casts its own shadow depending on the lighting.

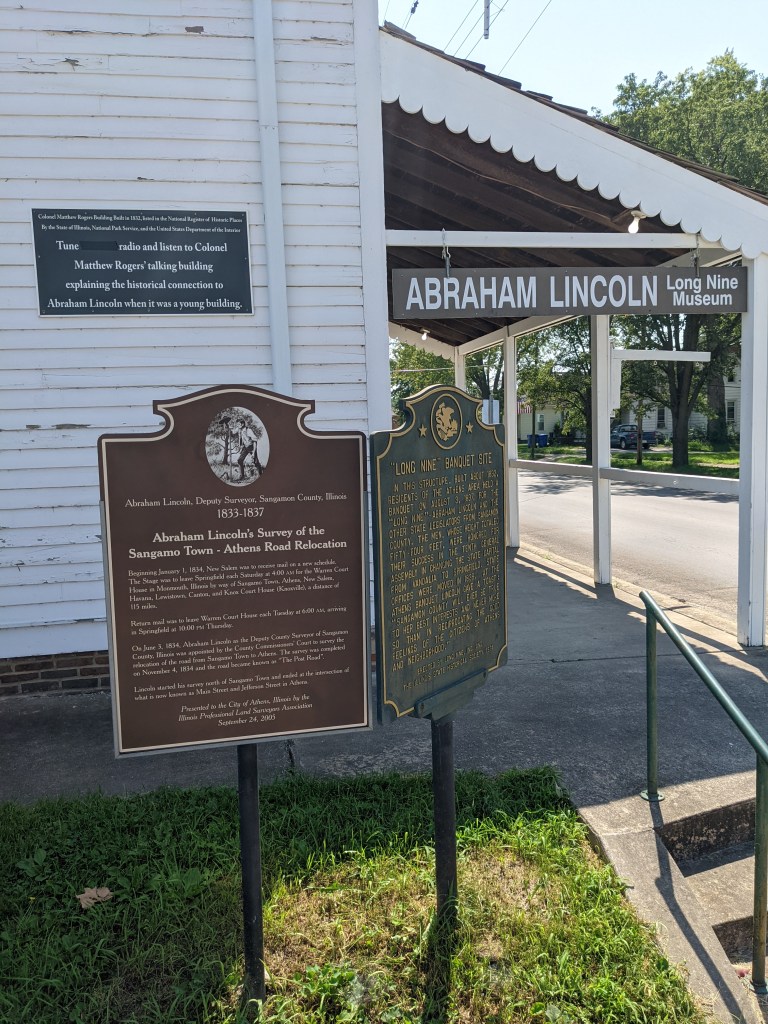

I had no idea who created the piece until I traveled to Athens (Pronounced Ay-thens) just a stone’s throw north of Springfield. I ventured there to meet with Jim Siberell, curator of the Long Nine Museum, who travels from his home in Portsmouth, Ohio during the summertime months to keep the museum open. Jim and I share a mentor in Dr. Wayne C. “Doc” Temple, the subject of my upcoming biography. As Mr. Siberell toured me through the museum, I spotted the exact plaque on display there. Of course, I asked for the history and Jim explained the artist’s connection to the museum. For those of you unaware, the Long Nine building is an important waymark of Illinois history. It was in this building, on the second floor, where Abraham Lincoln and six other state legislators (two of the members did not attend) decided to move the Illinois state capitol from Vandalia (near St. Louis) to the more centralized location of Springfield.

In 1837, a dinner party was held in the banquet room on the second floor to honor those legislators who were effective in passing a bill to relocate the capital. They earned the sobriquet of “The Long Nine” because together their height totaled 54 feet, each man being over 6′ tall or taller. Among the attendees was Abraham Lincoln, who at age twenty-seven was the youngest of the group. Lincoln gave the evening’s toast by saying, “Sangamon County will ever be true to her best interest and never more so than in reciprocating the good feeling of the citizens of Athens and neighborhood.” What this Hoosier finds most interesting is that when the delegates carved out the boundaries of Sangamon County, the home of the new state capitol, they left Athens out. Athens became a part of Menard County as did their neighbor, Lincoln’s New Salem.

Mr. Siberell toured me through the building and explained how Art Seiving had created the dioramas in the museum that recounted the stories of the men of The Long Nine in hand-carved wooden miniature displays. Each diorama’s characters were created by Seiving and the backgrounds were painted by artist, Lloyd Ostendorf. Siberell escorted me up the original stairway to the second-floor banquet room which features a stunning, massive oil painting by the late artist Lloyd Ostendorf showing Lincoln in formal dress toasting his colleagues. The mural covers an entire wall and is set against a table arranged much the same as it would have been on that fateful night. The visitor stands upon the original flooring of the banquet room where Lincoln gave his famous toast. The history room downstairs is a researcher’s dream. It contains many copies of Lincoln’s handwritten letters, documents from the history and restoration of the building, newspapers from the era, and historic photos. A trip to the basement reveals the building’s original fireplace, an arrray of period artifacts, and a scale model of Lincoln’s Tomb so big that it required the construction of a special pit to accommodate its massive size.

The March 23, 1973, Jacksonville (Illinois) Journal Courier reported. “Seiving has been working hard since January making the “Lincoln Head” plaques in his basement. He used a rubber mold taken from a carving…he pours into it the powdered molding material and fashions a Lincoln head of great exactness and beauty. During the past weeks, he has made enough of them to fill every available space in his basement. When he makes a few hundred more they will be delivered to a central point for use in Athens; he will then start on larger statues. The plaques being furnished are in white plaster material, but will be finished into a walnut appearance with a high polish and most attractive “feel” and “look”.

The article continues, “The classic dioramas made by Art Seiving will present all of those documented events which presented Lincoln in Athens, including hand-carved wooden figures, utensils, tools, buildings, and animals carved from wood.” One of Art’s carvings was titled, “Lincoln goes to school in Indiana”…It takes two people (himself and his wife) three nights to cut out 800 little paper leaves, and it’s no short job, either, to glue them to the branches, one by one. Others have taken longer. Mr. Seiving was five or six days just putting in 3,000 “tufts” of grass in his last completed scene. The grass is frayed rope strands, cut and dried and then glued down…And while you’d swear that the miniature pots and pans were made of metal, in actuality, most are simply wrapping paper glued to metal rings.” Sieving stated that it took him five to seven days to carve each figure, and one diorama alone featured 11 figures. His preferred medium was walnut with augmentations of birch wood.

Seiving is described as an “internationally known magician, sculptor and ventriloquist” whose “dummy” partner was known as “Harry O’Shea.” Of course, Art carved all of the ventriloquist dummies used in his acts himself. Art’s magic act was called the “Art Seiving and his Art of Deceiving.” Aside from the Long Nine Museum, he is best known for his dioramas at the Illinois State Museum, ‘Model of New Salem Village’ and wood sculptures including the ‘Egyptian Motif Clock’. Seiving’s George Washington carving is in the Smithsonian Institution’s collection.

Art’s Lincoln plaques are by no means rare but cannot be classified as common in the “collectorsphere”. I believe the Long Nine Museum still has a few for sale if memory serves, and one would set you back about the cost of a Starbucks coffee nowadays. To me, the value is not a monetary one, but rather the story the item tells. The version that Carter discovered (and so kindly gifted to me) is signed “Love, Laurie” on the back, making it all the more special to me. I tend to love these little travel souvenirs from the 1960-70s. I’m a space race Bicentennial kid who enjoys discovering these little treasures. They represent a vacation, a trip, a moment in someone’s life. Usually a kid, they are never confined to age, race, or gender. I appreciate that, in this age where everything handmade seems to come from China, most of these old travel souvenirs originate from where they were being sold. At that moment, they were the most important thing in that person’s life. Hand-picked with a smile and a “wow” to be taken home and enjoyed long after the trip concluded. A physical manifestation of a cherished memory. So thank you “Laurie” whomever or wherever you are for saving this little treasure for a history nerd like me. And most importantly, thank you Carter for thinking of me.

George Alfred Townsend and The War Correspondent Memorial Arch.

Original publish date April 11, 2024. https://weeklyview.net/2024/04/11/george-alfred-townsend-and-the-war-correspondent-memorial-arch/

Next week will witness another sad passing in American history: the 159th anniversary of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Because I live with this date dancing around in my head more than most, I want to share my experience (and admiration) for a peripheral character in that tragedy: George Alfred Townsend. Born in Georgetown, Delaware on January 30, 1841, Townsend was one of the youngest war correspondents during the American Civil War. Soon after graduation from high school (with a Bachelor of Arts) in 1860, Townsend began his career as a news editor with The Philadelphia Inquirer. In 1861, he moved to the Philadelphia Press as city editor. As the war broke out, he worked for the New York Herald as a war correspondent in Philadelphia.

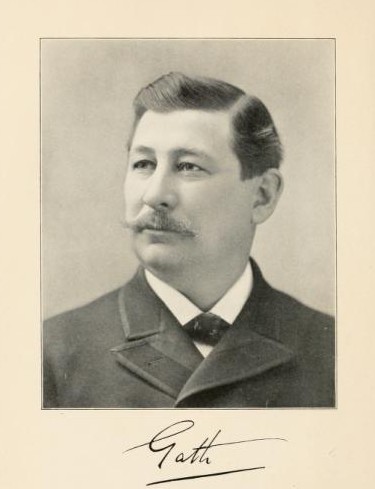

By April 1862, George got his big break when General George McClellan rode through Philadelphia on his way to Washington. That fortuitous meeting would propel young Townsend to exclusive access to many of the Civil War’s greatest battles. One of America’s first nationally syndicated columnists, Townsend used the pen name “Gath” for his newspaper columns. Gath was an acronym of his initials with the addition of an “H” at the end. Friends and contemporaries like Mark Twain, Bret Harte, and Noah Brooks, claimed the “H” stood for “Heaven” while wags and rivals claimed it stood for “Hell.” Gath himself was inspired by the biblical passage uttered by David after the death of King Saul in II Samuel 1:20, “Tell it not in Gath, publish it not in the streets of Askalon.”

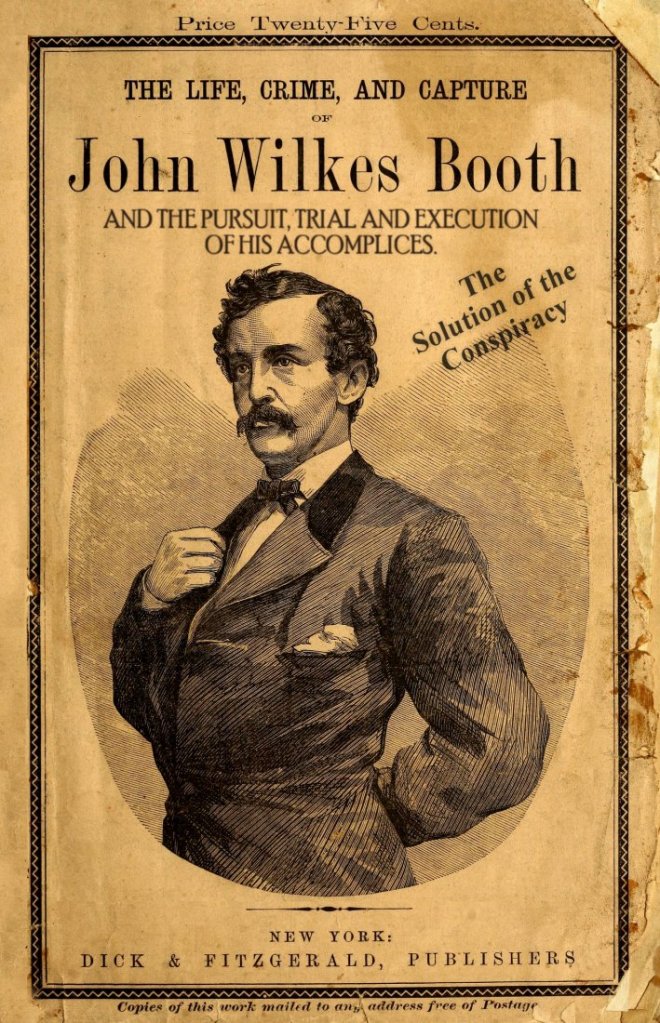

While Townsend won accolades for his work covering the war, it was his coverage of the Lincoln assassination that he is best remembered for. His detailed columns (which he called “letters”) about the tragedy were filed between April 17 – May 17 and would later be published as The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth. Published in 1865, Townsend’s book offers a full sketch of the assassin, the conspiracy, the pursuit, trial, and execution of his accomplices. As a lifelong student of Lincoln, I have read countless books, articles, letters, and various accounts centered on his life. It was in George Alfred Townsend’s “letters” that I found my holy Grail. Townsend’s description of Lincoln in his coffin made me feel as if I were standing there myself. His description of Lincoln’s office left me awestruck and wishful. In my opinion, it would be hard to find a more worthy example of Victorian journalism than these excerpts from Gath’s “letters”.

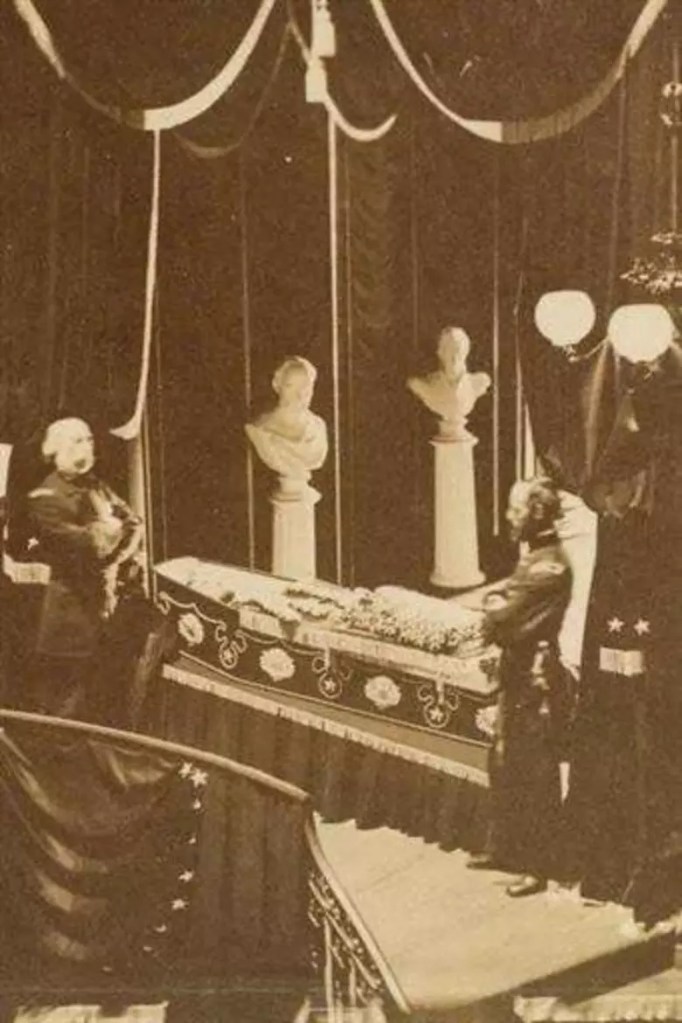

“Deeply ensconced in the white satin stuffing of his coffin, the President lies like one asleep. Death has fastened into his frozen face all the character and idiosyncrasy of life. He has not changed one line of his grave, grotesque countenance, nor smoothed out a single feature. The hue is rather bloodless and leaden; but he was always a sallow. The dark eyebrows seem abruptly arched; the beard, which will grow no more, is shaved close, save the tuft at the short small chin. The mouth is shut, like that of one who had put the foot down firm, and so are the eyes, which look as calm as slumber. The collar is short and awkward, turned over the stiff elastic cravat, and whatever energy or humor or tender gravity marked the living face is hardened into its pulseless outline. No corpse in the world is better prepared according to appearances. The white satin around it reflects sufficient light upon the face to show us that death is really there; but there are sweet roses and early magnolias, and the balmiest of lilies strewn around, as if the flowers had begun to bloom even upon his coffin. Looking on interruptedly! for there is no pressure, and henceforward the place will be thronged with gazers who will take from the site its suggestiveness and respect. Three years ago, when little Willie Lincoln died, Doctors Brown and Alexander, the embalmers or injectors, prepared his body so handsomely that the President had it twice disinterred to look upon it. The same men, in the same way, have made perpetual these beloved lineaments. There is now no blood in the body; it was drained by the jugular vein and sacredly preserved, and through a cutting on the inside of the thigh the empty blood vessels were charged with the chemical preparation which soon hardened to the consistence of stone. The long and bony body is now hard and stiff, so that beyond its present position it cannot be moved any more than the arms or legs of a statue. It has undergone many changes. The scalp has been removed, the brain taken out, the chest opened and the blood emptied. All that we see of Abraham Lincoln, so cunningly contemplated in his splendid coffin, is a mere shell, an effigy, a sculpture. He lies in sleep, but it is the sleep of marble. All that made the flesh vital, sentiment, and affectionate is gone forever.”

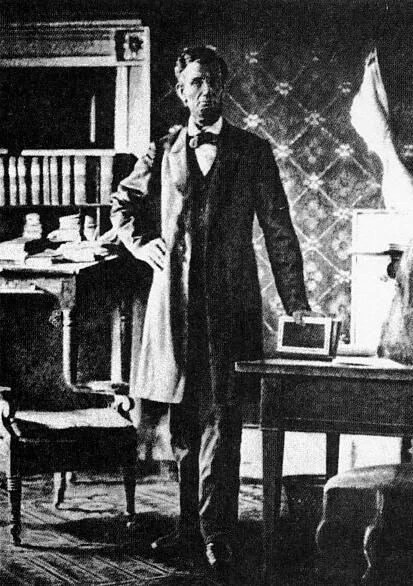

On May 14, 1865, the day Abraham Lincoln’s body was placed on the funeral train to leave Washington DC forever, Townsend visited the White House. Mary Lincoln still resided there with her beloved son Tad, too distraught to leave the White House. “I am sitting in the President’s office. He was here very lately, but he will not return to dispossess me of the high-backed chair he filled so long, nor resume his daily work at the table where I am writing. There are here only Major Hay (Salem Indiana’s John Hay, Lincoln’s private secretary) and the friend who accompanies me. A bright-faced boy runs in and out, darkly attired, so that his fob chain of gold is the only relief to his mourning garb. This is little Tad, the pet of the White House. That great death, with which the world rings, has made upon him only the light impression which all things make upon childhood. He will live to be a man pointed out everywhere, for his father’s sake; and as folks look at him, the tableau of the murder will seem to encircle him.”

Townsend further describes Lincoln’s office, just as he left it. “The room is long and high, and so thickly hung with maps that the color of the wall cannot be discerned. The President’s table at which I am seated adjoins a window at the farthest corner; and to the left of my chair as I reclined in it, there is a large table before an empty grate, around which there are many chairs, where the cabinet used to assemble. The carpet is trodden thin, and the brilliance of its dyes is lost. The furniture is of the formal cabinet class, stately and semi-comfortable; there are bookcases sprinkled with the sparse library of a country lawyer, but lately plethoric, like the thin body which has departed in its coffin. Outside of this room, there is an office, where his secretaries sat – a room more narrow but as long – and opposite this adjacent office, a second door, directly behind Mr. Lincoln’s chair leads by a private passage to his family quarters. I am glad to sit here in his chair, where he has spent so often, – in the atmosphere of the household he purified, and the site of the green grass and the blue river he hallowed by gazing upon, in the very center of the nation he preserved for the people, and close the list of bloodied deeds, of desperate fights of swift expiations, of renowned obsequies of which I have written, by indicting at his table the goodness of his life and the eternity of his memory.”

“They are taking away Mr. Lincoln’s private effects, to deposit them wheresoever his family may abide, and the emptiness of the place, on this sunny Sunday, revives that feeling of desolation from which the land has scarce recovered. I rise from my seat and examine the maps; they are from the coast survey and engineer departments, and exhibit all the contested grounds of the war: there are pencil lines upon them where someone has traced the route of armies, and planned the strategic circumferences of campaigns. Was it the dead President who so followed the March of Empire, and dotted the sites of shock and overthrow? So, in the half-gloomy, half-grand apartment, roamed the tall and wrinkled figure whom the country had summoned from his plain home into mighty history, with the geography of the Republic drawn into a narrow compass so that he might lay his great brown hand upon it everywhere. And walking to and fro, to and fro, to measure the destinies of arms, he often stopped, with his thoughtful eyes upon the carpet, to ask if his life were real and he were the arbiter of so tremendous issues, or whether it was not all a fever-dream, snatched from his sofa in the routine office of the Prairie state.”

“I see some books on the table; perhaps they have lain there undisturbed since the reader’s dimming eyes grew nerveless. A parliamentary manual, a thesaurus, and two books of humor, “Orpheus C. Kerr,” and “Artemis Ward.” These last were read by Mr. Lincoln in the pauses of his hard day’s labor. Their tenure here bears out the popular verdict of his partiality for a good joke; and, through the window, from the seat of Mr. Lincoln, I see across the grassy grounds of the capitol, the broken shaft of the Washington Monument, the long bridge and the fort-tipped Heights of Arlington, reaching down to the shining riverside. These scenes he looked at often to catch some freshness of leaf and water, and often raised the sash to let the world rush in where only the nation abided, and hence on that awful night, he departed early, to forget this room and its close applications in the abandon of the theater. I wonder if it were the least of Booth’s crimes to slay this public servant and the stolen hour of recreation he enjoyed but seldom. We worked his life out here, and killed him when he asked a holiday.”

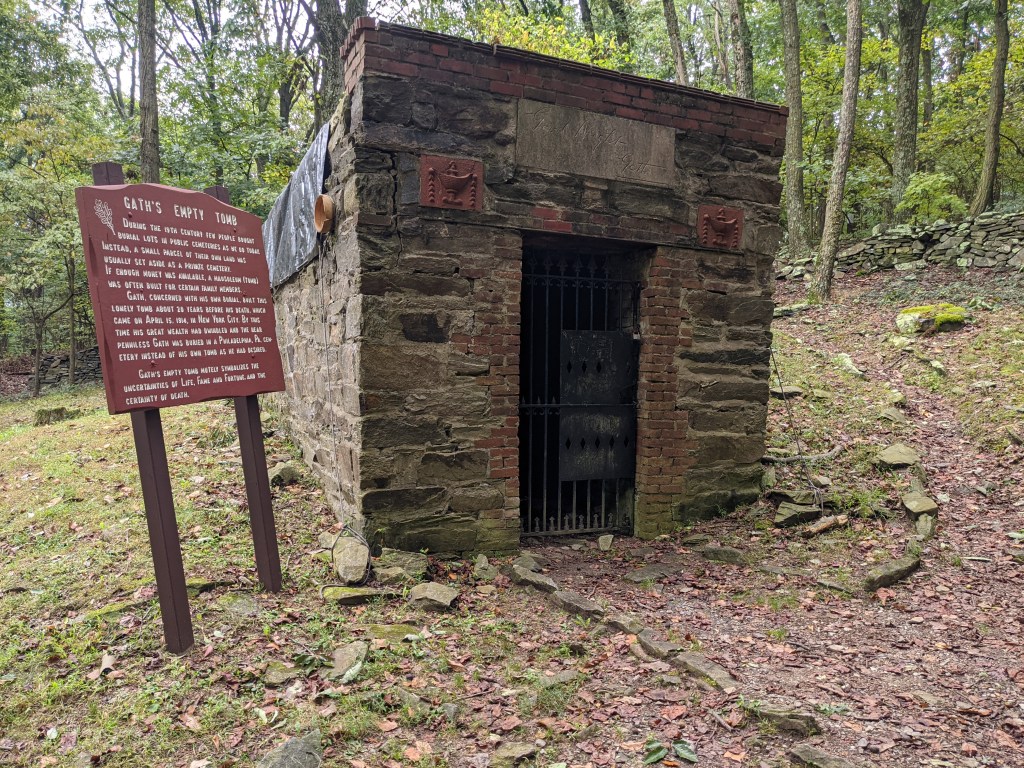

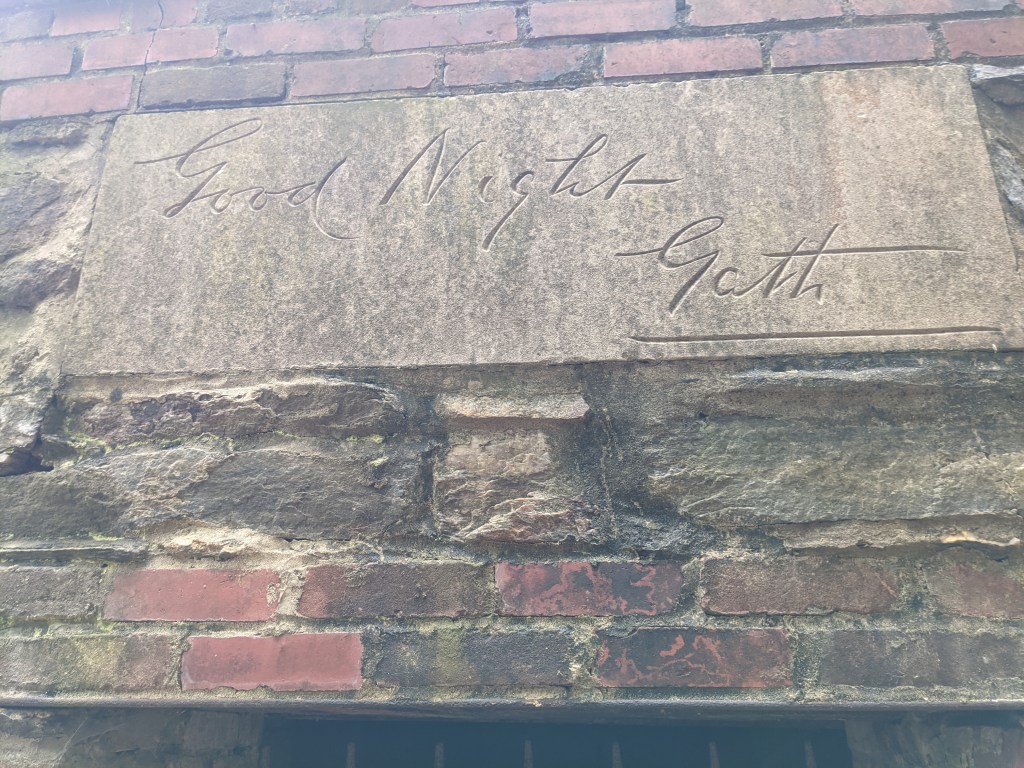

As one of the most successful journalists of his day, Townsend accumulated a tidy fortune. He used much of that fortune to build a 100-acre baronial estate near Crampton’s Gap, South Mountain, Maryland known as “Gapland”. The Civil War Battle of Crampton’s Gap was fought as part of the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, 1862, and resulted in 1,400 combined casualties. Tactically the battle resulted in a Union victory because they broke the Confederate line and drove through the gap. Strategically, the Confederates were successful in stalling the Union advance and were able to protect the rear. Gath literally bought the battlefield upon which he built his estate. The estate was composed of several buildings, including Gapland Hall, Gapland Lodge, the Den and Library Building, and a brick mausoleum (notable for its inscription of “Good Night Gath” above the entrance).

In 1896, Townsend built a monument to war correspondents to memorialize the contributions of his colleagues North and South. Dedicated in 1896, The War Correspondent Memorial Arch is 50 feet high and 40 feet wide and is the only monument in the world dedicated solely to war correspondents. Not only does the arch stand on Townsend’s original estate (operated by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources), it also rests smack dab in the middle of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail. Furthermore, the woods surrounding Gapland and the nearby town of Burkittsville were the setting for the 1999 horror film Blair Witch Project.

Last September, I traveled to the Catoctin Mountains to visit Townsend’s estate not far from the Antietam battlefield. Townsend’s Gapland estate is now known as Gathland State Park. Several buildings still stand, including Gapland Hall (which is the park headquarters) and the mausoleum, while other buildings are mere shadows of their former self. Townsend left Gapland in 1911 and died in New York City three years later on April 15, 1914. The 49th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s death. He was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.

His brick mausoleum, fronted by an ominous-looking iron gate causing it to look more like a jail cell than a tomb, stands empty, its roof slowly caving in. Although the object of my quest was The War Correspondent Memorial Arch, I could not help but spend most of my time seated beneath that empty tomb smoking a cigar. While the hale and hearty hikers pausing briefly at the foot of the Appalachian Trail might not have appreciated my vice, as I stared at the epitaph above the iron gate above Townsend’s unused tomb, George Alfred Townsend would understand. Good Night Gath.

99 Birthday Cards for Doc.

https://weeklyview.net/2023/02/02/99-birthday-cards-for-doc/

PLEASE SHARE!

February 5, 2023.

Friends, please consider joining me in a project celebrating the 99th birthday of the Dean of all Abraham Lincoln scholars from Springfield, Illinois:

Dr. Wayne C. “Doc” Temple.

I have been working on a biography of Doc for some time now. For nearly 70 years, Doc has researched, written, and published more than 20 books and over 300 articles on Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, Indigenous tribes, and Midwest history. Along the way, Doc has graciously volunteered his time, knowledge & wisdom with countless students and scholars along the way. Most of today’s Lincoln scholars have consulted Doc for facts in their work.

This will be Doc’s first birthday since losing Sandy, his wife of 42 years, last March. Doc is a member of America’s greatest generation having fought bravely for the United States in the European theatre, once actually standing in an open road firing a Thompson Sub-machine gun at a German fighter plane strafing his unit. He is an amazing man.

I ask that you join me in sending a birthday card or friendly note to Doc (he doesn’t do e-mail) in time for his 99th birthday (February 5, 2023) in care of the address below. Please share this humble announcement to your page and we’ll see if we can’t get 99 cards for Doc’s 99th birthday. His personal archives will be donated to the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield and these birthday cards will be preserved among that collection. Thank you for your consideration.

Wayne “Doc” Temple

c/o Books on the Square

427 East Washington Street

Springfield, IL 62701

————–

Doc’s historical resume is unchallenged. In my opinion, he is our nation’s greatest living Lincoln scholar. I am just one of the legion of Lincoln scholars he has helped and encouraged along the way. Doc served as chief deputy director of the Illinois State Archives for over 50 years (1964-2016), Secretary-treasurer of the National Lincoln-Civil War Council during the 100th anniversary Centennial years (1958-1964), and editor / associate of the Lincoln Herald since 1973.

I have listed Doc’s “resume” below. As you can see, it is quite impressive.

Doc’s education credentials & historical resume:

AB cum laude, University of Illinois, 1949; AM, University of Illinois, 1951; Doctor of Philosophy, University of Illinois, 1956; Lincoln Diploma of Honor (Illinois’ highest civilian award), Dean of history at Lincoln Memorial U., Harrogate, Tennessee, 1963. Wayne Calhoun Temple has been listed as a noteworthy Historian by Marquis Who’s Who.

Curator ethnohistory, Illinois State Museum, 1954-1958; editor-in-chief, Lincoln Herald, Lincoln Memorial U., 1958-1973; associate editor, Lincoln Herald, Lincoln Memorial U., since 1973; also director department Lincolniana, director university press, John Wingate Weeks professor of history, Lincoln Herald, Lincoln Memorial U., 1958-1964; with, Illinois State Archives, since 1964; chief deputy director, Illinois State Archives. Lecturer United States Military Academy, 1975. Secretary-treasurer National Lincoln-Civil War Council, 1958-1964.

Member bibliography committee Lincoln Lore, since 1958. Honorary member Lincoln Sesquicentennial Commission, 1959-1960. Advisory council United States Civil War Centennial Commission, 1960-1966.

Major Civil War Press Corps, since 1962. President Midwest Conference Masonic Education, 1985.

Doc’s books include:

Lincoln the Railsplitter 1961. (listed in the top 100 Lincoln books ever written)

Stephen A. Douglas, freemason Stephen A. Douglas, Freemason.

Abraham Lincoln and Others at the St. Nicholas.

Lincoln’s Confidant: The Life of Noah Brooks (The Knox College Lincoln Studies Center) by Wayne C. Temple, Douglas L. Wilson, et al. / Nov 30, 2018

Abraham Lincoln: From Skeptic to Prophet 1st Edition by Wayne C. Temple (1995)

Alexander Williamson: Friend of the Lincolns (Special publication)

Lincoln’s Surgeons at His Assassination Hardcover – October 29, 2015

BY SQUARE AND COMPASS: THE BUILDING OF LINCOLN’S HOME AND ITS SAGA.

Lincoln-Grant: Illinois militiamen Lincoln-Grant: Illinois militiamen

Indian Villages of the Illinois Country: Historic Tribes (Scientific Papers, Vol 2, Pt 2)

Membership:

Sponsor Abraham Lincoln Bay, Washington National Cathedral. Member Illinois State Flag Commission, since 1969. Trustee, regent Lincoln Academy Illinois, 1970-1982, Bicentennial Order Lincoln, 2009.

Board governors St. Louis unit Shriners Hospitals for Crippled Children, 1975-1981. Commissioning committee, honorary crew member and plank owner United States Ship Springfield submarine, since 1990. Honorary crew member United States Ship Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier, since 1989.

With United States Army, 1943-1946, general Reserve (retired). Fellow Royal Society Arts (life). Member National Rifle Association, Knight Templar (Red Cross Constantine), Lincoln Group District of Columbia (honorary), University Illinois Alumni Association, Illinois State History Society, Board of Advisors, The Lincoln Forum, Illinois Professional Land Surveyors Association, Illinois State Dental Society (citation plague 1966), Reserve Officers Association, Lincoln Fellowship of Wisconsin, Iron Brigade Association (honorary life), Military Order Loyal Legion United States (honorary companion), Military Order Foreign Wars United States, Army and Navy Union, Masons (33 degree, Meritorious Service award, grand representative from Grand Lodge of Colorado), Shriners, Kappa Delta Pi, Phi Alpha, Phi Alpha Theta (Scholarship Key award), Chi Gamma Iota, Phi Beta Kappa, Tau Kappa Alpha, Alpha Psi Omega, Sigma Pi Beta (Headmaster), Sigma Tau Delta (Gold Honor Key award for editorial writing), Zeta Psi.