Tag: Abraham Lincoln

Obituary for Wayne C. “Doc” Temple”

Doc Temple’s century of service is complete, his earthly journey concluded, and he has embarked on the most anticipated trip of his long and happy life, carried on the wings of cardinals to reunite in heaven with his beloved wife Sunderine. Doc’s life, by his own admission, was a dream come true. Born in Ohio’s fields of plenty, Doc was an old soul from the start. With nary a penny in his pocket, at the age of five he carried an old broken pocket watch and chain found abandoned in a farmer’s field as part of his daily attire. He turned that love of timepieces into the preeminent collection of Illinois Watch Company pocket watches known in the state. Governors, senators, congressmen, generals, scholars, and friends today carry an “A. Lincoln” or “Bunn Special” pocket watch with them today, courtesy of Wayne C. Temple. Other creatures received his bounty, too: he fed the cardinals outside his home on Fourth Street Court assiduously and considered every red bird that benefited from his efforts as an earthly manifestation of his wife Sandy, reminding him, over the past three years, that she stood with open arms on the rainbow bridge, awaiting his arrival.

While historians know that Doc was chosen as one of the top 150 graduates of all time from the University of Illinois during its sesquicentennial year of 2017, not many realize that Doc was also an accomplished poet, living his life with poetry in his soul. He sprouted as a poor Ohio farm boy with an unquenchable thirst for history, education, and life, with his first love the English language. He put that adoration for the printed word to good use in elocution contests and essays that were the first signs of his innate talent. From those humble beginnings, Doc served his country in Europe, slept on castle floors, befriended a General named Eisenhower who would soon become President, and drank the wine of emperors gifted to him by grateful war-torn communities that he literally brought back to life with his engineering skills. Of course, Doc shared Napoleon’s wine with his battle buddies. Doc’s flame burned brighter than any other historian in Illinois’s history, and the prowess of his Lincoln scholarship was unchallenged for half a century. He spent a career burning holes in the pages of others’ older history by his meticulous research, yet Doc’s flame always warmed, never burned those around him. He was quick to share information with all who sought his advice. Whether you were a budding scholar, land surveyor, dentist (yes, Doc was an honorary dentist), lawyer, politician, historical enthusiast, tourist, or student, Doc always had time to lend a hand in the most generous fashion. He never concerned himself about attribution or credit; his mantra was always “Get the information out there.” Some of it was new information, too: Each year he wrote Sandy an original poem, in rhyme, for her birthday or anniversary.

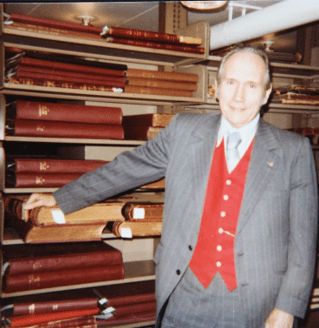

Although Doc stood front and center for every important Illinois event, commemoration, or big reveal for the past seven decades, you’d never know it by his demeanor. If he wasn’t on the dais, he was in the front row. During his career in the Archives, he was just as excited to meet Hoss Cartwright’s school teacher as he was to meet the Vice-President of the United States. Doc’s presence will be sorely missed, his record of 54 years, 7 months service to the state of Illinois may never be surpassed, and his space in the Lincoln field will remain unfilled. His passing came with typical military precision, bisecting the clock at precisely 1230 hours, the hands on the clock in an upswing, moving up, not down, on the final day of March. Doc’s transition occurred exactly at the conclusion of his life’s seasonal winter to burst forth to the heavenly spring we all hope awaits our final journey. Doc would remind us all, with a wink and a smile, that he also waited until after the St. Louis Cardinals home opener had arrived.

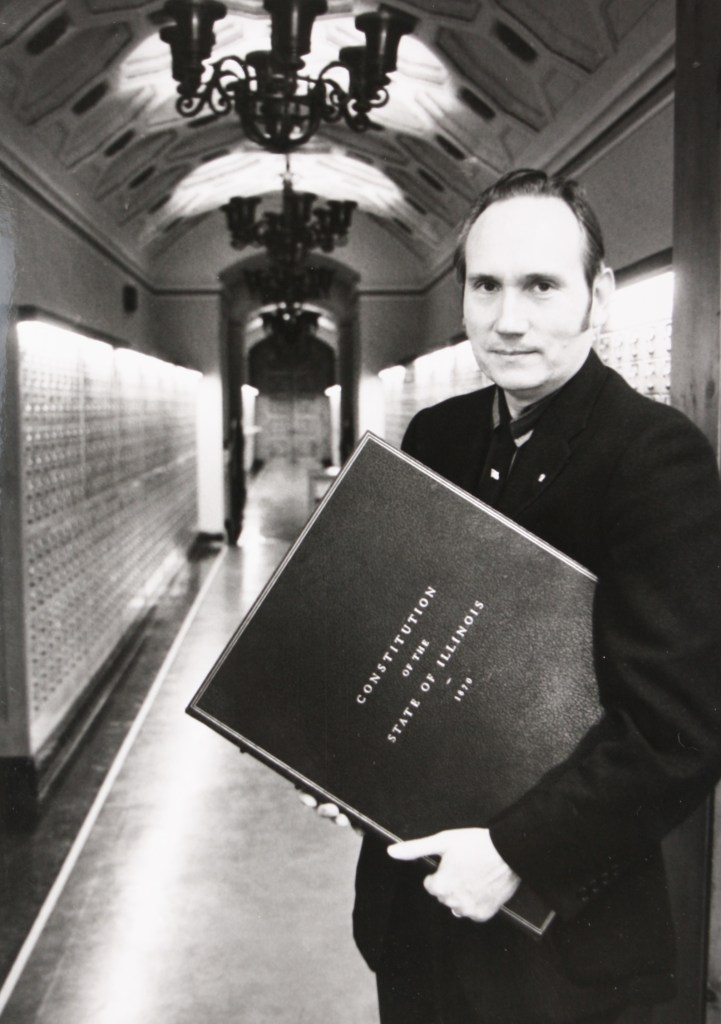

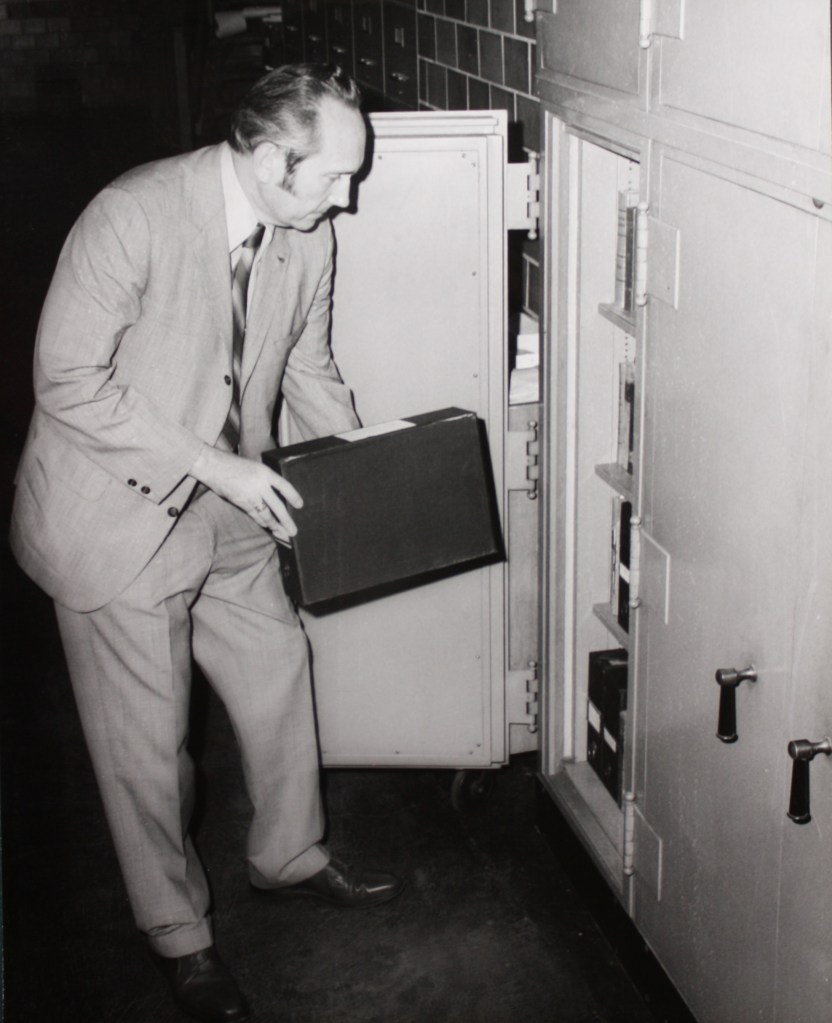

Wayne Calhoun Temple, the dean of Lincoln studies and for half a century the mainstay of the Illinois State Archives, died peacefully on March 31, 2025, at a care facility in Chatham, Illinois. Devoted friends Teena Groves and Sharon Miller were present Wayne Calhoun Temple, the dean of Lincoln studies and for half a century the mainstay of the Illinois State Archives, died peacefully on March 31, 2025, at a care facility in Chatham, Illinois. Devoted friends Teena Groves and Sharon Miller were present and biographer Alan E. Hunter was on the phone with them at the time of his passing. He was predeceased by his beloved wife Sandy (2022), and by his parents Howard (1971) and Ruby (1978) Temple, of Richwood, Ohio.. He was predeceased by his beloved wife Sandy (2022), and by his parents Howard (1972) and Ruby (1977) Temple, of Richwood, Ohio.

Temple, known to all for 60 years as “Doc,” was born on a small family farm two miles east of Richwood (about 40 miles north of Columbus), on Feb. 5, 1924. He liked to note that he shared a birthday with Lincoln’s mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln. He was an only child. From his mother, a teacher, he learned literature, history, and music; from his father, he learned how to ride, how to shoot, how to plant and reap. An oft-repeated story is how at age 9 years he encouraged his parents to go see the fair in Chicago in 1933 as they wished. He persuaded them that he’d be fine and he was – he had the horse, the cart, and the rifle.

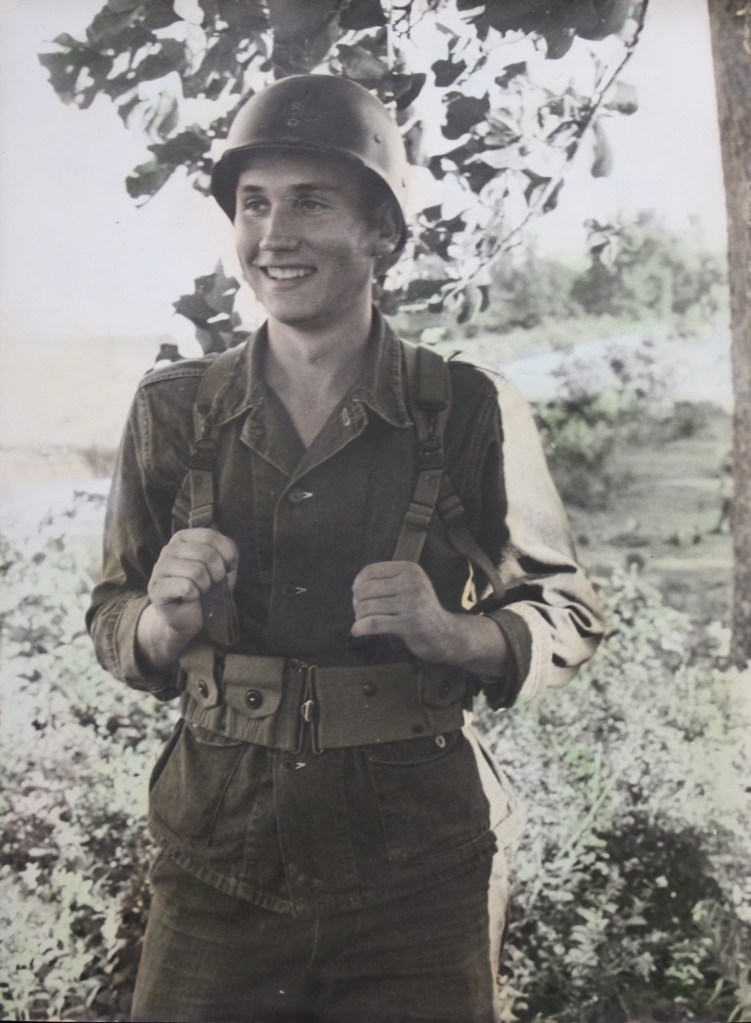

After a one-room-schoolhouse start, in high school he was valedictorian and ran on a championship 1,500-yard 4-man relay team. He played clarinet in a traveling band of adult men. In 1941, he entered Ohio State University on a football scholarship, intending to study chemistry. He was soon drafted into the Army Air Corps and sent to Urbana, Illinois, for training as an engineer. He and his mates were sent to North Carolina for special training; then to Kansas for ordnance production.

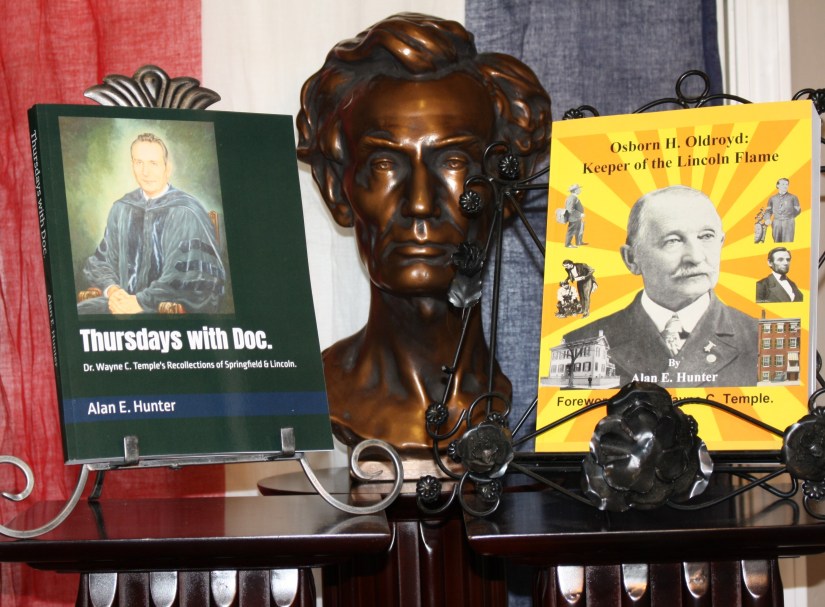

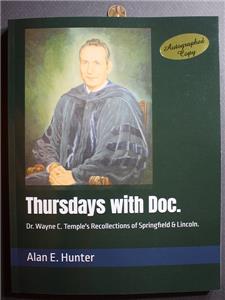

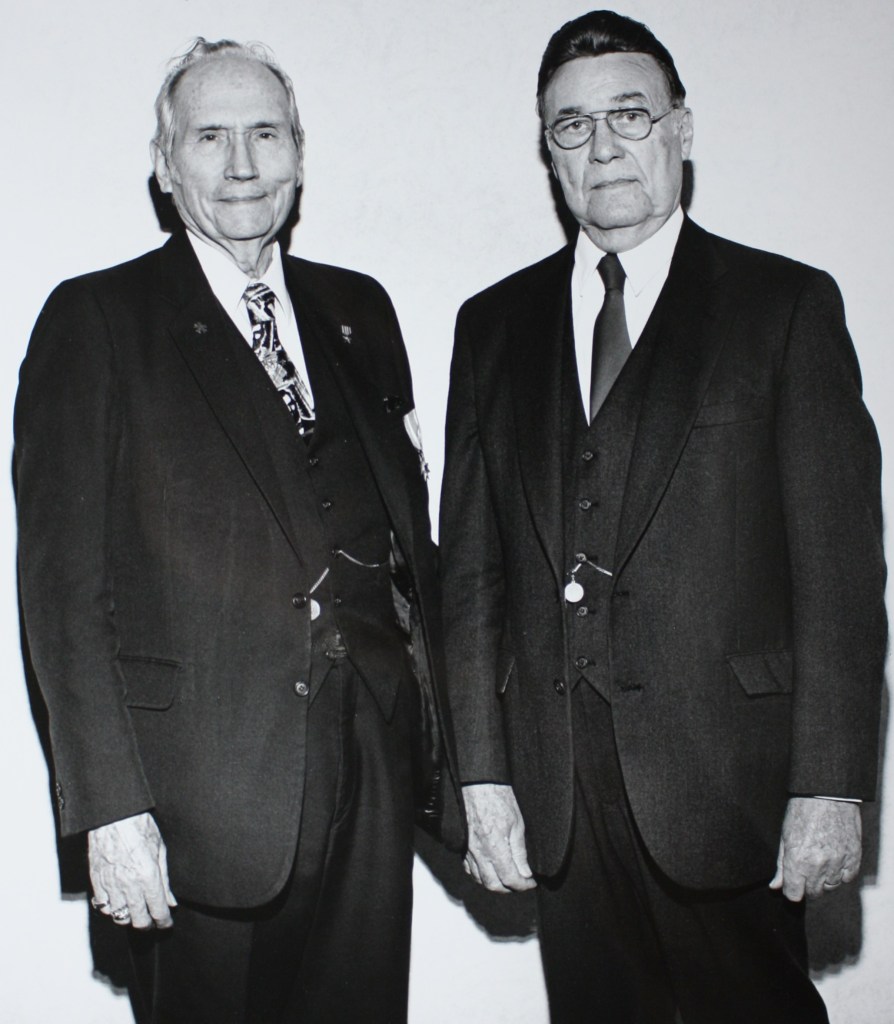

He spent 1945-46 in Europe, and at age 21 as a Tec 5 in the Signal Corps (grade of a sergeant), he helped install new airfields and radio communications, some of it personally for General-in-Chief Eisenhower. Many more details are found in Alan E. Hunter’s remarkable oral-history-as-life-study, Thursdays with Doc (2025), copies of which Temple signed in his last months of life.

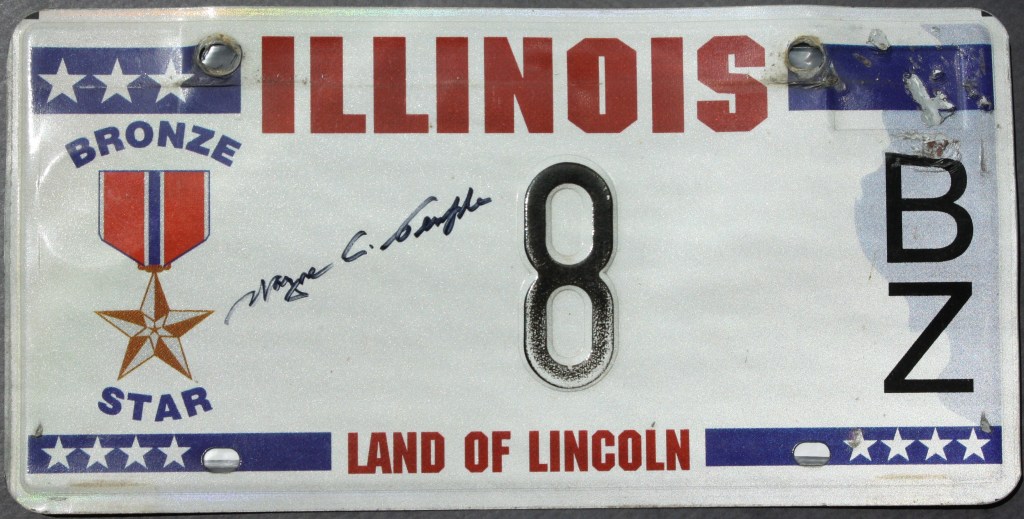

He was awarded the Bronze Star for his one-man battle with a Luftwaffe pilot who strafed their camp on the Franco-German border in the last weeks of the war. While others dove for the ditch, Doc used his favorite weapon, the Thompson submachine gun, to fire upward at the plane. “Did you hit him?” Doc was later asked. “I don’t know, but he didn’t come back.”

After the war he returned to the U. of Illinois, earning a war-interrupted B.A. in History and English. Here, he was discovered by Prof. James G. Randall, the first academic historian of Lincoln, and became his graduate student and research assistant until “Jim’s” death in 1953. Temple helped him write vol. 3 of the tetralogy Lincoln the President (1945-55) and rough out vol. 4 although a more senior scholar got credit as co-author. Temple also helped Ruth Randall with her popular and “junior” histories about the Lincolns and women of the Civil War era, and corresponded with her until her death in 1971.

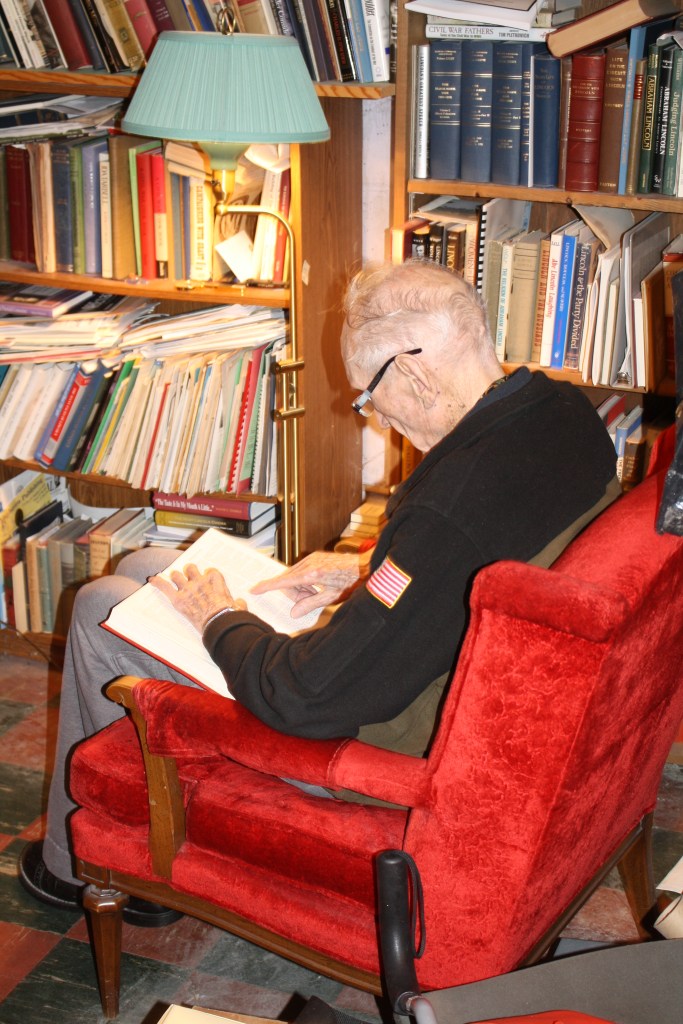

His first book was commissioned and remunerated handsomely by Thorne Deuel of the Illinois State Museum, on Indian Villages of the Illinois Country (1958), still considered a model of research and analysis. From there Temple took his wife Lois McDonald Temple to Lincoln Memorial University, Harrogate, Tennessee, to head up the history department. They remained in touch for decades with some of the young women who assisted in the department. He edited The Lincoln Herald there, making it the best periodical in the field, and remained as editor till the mid-1970s, long after the Illinois State Archives in 1964 brought him on staff. For decades before his retirement there in 2016 he was permanent Chief Deputy Director. (Lois died in 1978; Doc and Sandy met and married in 1979.) He no longer taught classrooms, helping instead an average of 150 people per month for a half-century who called, wrote, or walked in with questions at the Archives – in addition to speaking and writing publicly more than most fulltime professors. Land surveying, one of Temple’s many skills, proved invaluable for the dozen survey questions a month on that topic, alongside tracing the course of legislative bills old or new, gubernatorial proclamations, or judicial rulings. He mastered the use of old registers, microfilm, and the typewriter, but never took to computers. Nine secretaries of State, of both parties, kept Temple on, recognizing his value to the state and to the public; tech-savvy assistants like his friend Teena Groves made the office efficient, complementing Doc’s top-notch research work.

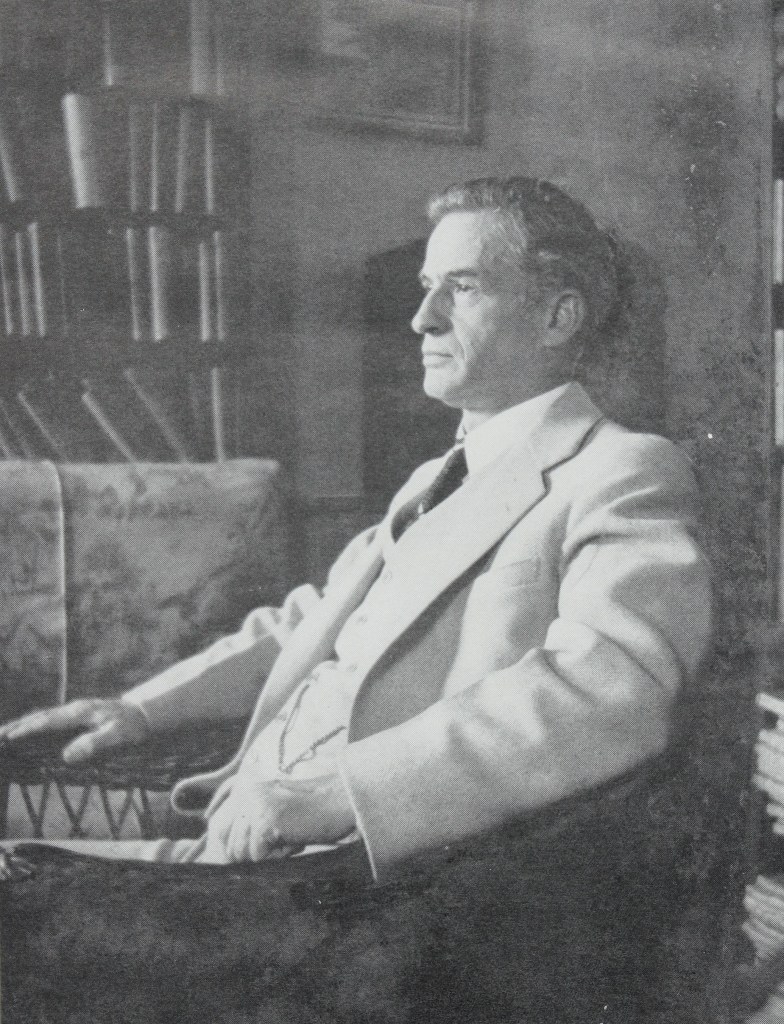

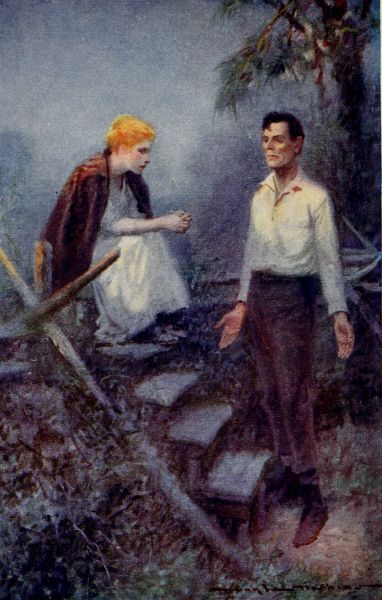

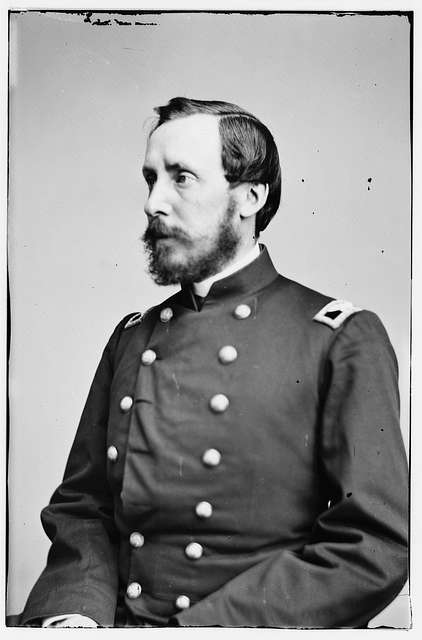

Dayton Ohio artist Lloyd Ostendorf.

At the popular level he engaged artist Lloyd Ostendorf to illustrate the Lincoln Herald with Temple’s precise historical notes on people’s heights, demeanor, clothing, armaments, supported by background architecture and horsetack, for the best historic illustrations of any American’s circle of friends and colleagues. These scenes were set in dozens of Illinois cities and towns around the legal or political circuit, plus Lincoln’s White House years. Supporting local-history projects with Phil Wagner, John Eden of Athens, the Masonic Lodge, and towns themselves, Temple also helped re-create dramatic moments of the past. The Lincoln Academy of Illinois made him a Regent in the 1960s with a nomination by a governor from each party, and he was elected a Laureate in 2009, the highest honor in the State’s gift. Helping in 1969 to reactivate the 114th Illinois Volunteer Infantry of the Civil War era, he rose in its ranks from Lt. Col. to full General, presiding at dozens of ceremonies. Nationally he was a member of the U.S. Civil War Centennial Commission (1960-1965); was invited to recite the Gettysburg Address on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial with President Nixon and other officials present in 1971, then to speak to the Senate about the Lincoln boys’ Scottish-born tutor Alexander Williamson; and in 1988 was present for the commissioning of the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln. Privately and at work he was asked to weigh in on the authenticity of dozens of Lincoln documents owned by private collectors.

Temple’s published works remain the testament to his great energies and skill. With wife Sunderine, a.k.a. Sandy, who for 40 years was a head docent at the Old State Capitol, he wrote Illinois’ Fifth Capitol: The House that Lincoln Built and Caused to Be Rebuilt (1837-1865) (1988), the standard work on its initiation, contracts, costs, furnishing, refurbishing, and historic moments such as Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech in 1858. In like vein he wrote up the Lincoln Home, in By Square and Compasses (1984; updated 2002). For shorter works he found or recovered the stories of people high and low, including Mariah Vance, the Lincolns’ African-American laundress; Barbara Dinkel, a German-born widow down the block; two Portuguese immigrants nearby; Robert Lincoln’s ability to play the piano; and father Abraham’s formal commission as an Illinois militia officer after the Black Hawk War of 1832, which he maintained throughout his life by attending the annual muster. C. C. Brown, namesake of the oldest continuous business in Illinois – the law firm Brown, Hay, & Stephens (est. 1828) — offered some thoughts on working with Lincoln which Temple found and turned into a booklet in 1963. Probably his most enduring book will be Abraham Lincoln: From Skeptic to Prophet (1995), on the religious views, which Temple called not merely a religious study but “really a biography of the Lincoln family.” Lincoln’s many connections to Pike County introduced a book about the area’s Civil War record; his trip through the Great Lakes in 1849 gave rise to a booklet about the Illinois & Michigan Canal and Lincoln’s patented invention. Some of the best of Temple’s 500 to 600 articles are being collected into a book edited by Steven Rogstad.

Personally Temple was highly generous, helping Sandy’s distant family when in need, serving as an Elder and teacher at the First Presbyterian Church, and endowing the UI Urbana History Dept. with funds from his estate. On behalf of wife Lois’s nephew, Temple headed a Boy Scout troop in town. Doc gave his father’s canful of ancient Indian artifacts dug from the Ohio farm to the public library in Richwood, Ohio, as one of his last acts, though he could have sold them for many thousands of dollars. When Temple learned that his barber, a father of five, could not afford to send his bright youngest son to college, Temple spoke to Congressman Paul Findley, who got the young man appointed to the Academy at West Point, and a successful military career was launched. Temple’s collection of 3,000 books is bound for UI Springfield’s Lincoln Studies Center, while his fine collection of artworks as well as personal papers will go to the Presidential Library and Museum.

In the opinion of the person who succeeds Temple as the dean of Lincoln historians, Prof. Michael Burlingame of UI Springfield, Doc “displayed an uncanny ability to unearth new information about Lincoln through painstaking research … For over eight decades, he tenaciously filled many niches in the Lincoln story.” His neighbor of 43 years, Sharon Miller, said, “Doc was simply a wonderful man. But he missed Sandy too much to keep going.”

A memorial service will be held on Thursday, April 10th, at 10:00 a.m. at Staab Funeral Home, S. 5th St. in Springfield. Burial will take place at 1:00 p.m. at Camp Butler National Cemetery, next to Sandy temple’s gravesite. A reception at the St. Paul’s #500 A.F. & A.M. Lodge on Rickard Drive will follow.

Fun conversation with Dave Taylor about Doc Temple & Osborn Oldroyd.

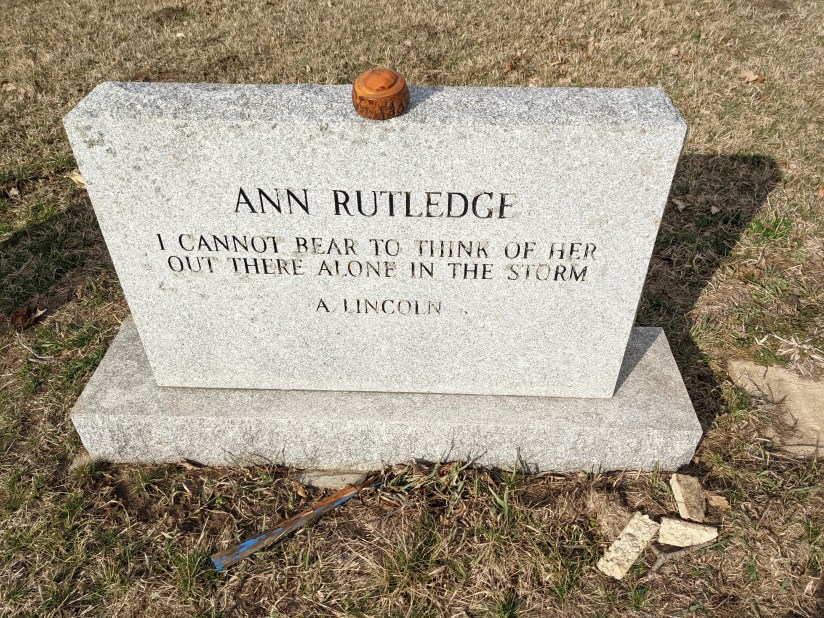

In Search of Ann Rutledge: Lincoln’s lost love.

Original publish date March 23, 2023. https://weeklyview.net/2023/03/23/in-search-of-ann-rutledge-lincolns-lost-love/

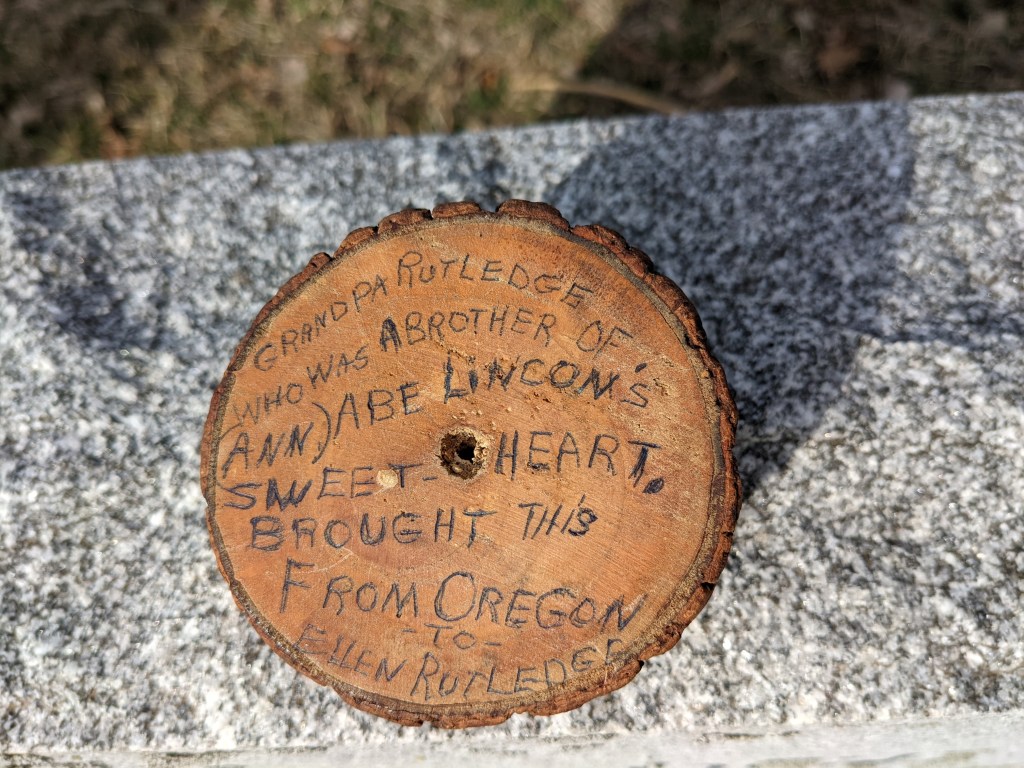

(Author’s trinket explained below)

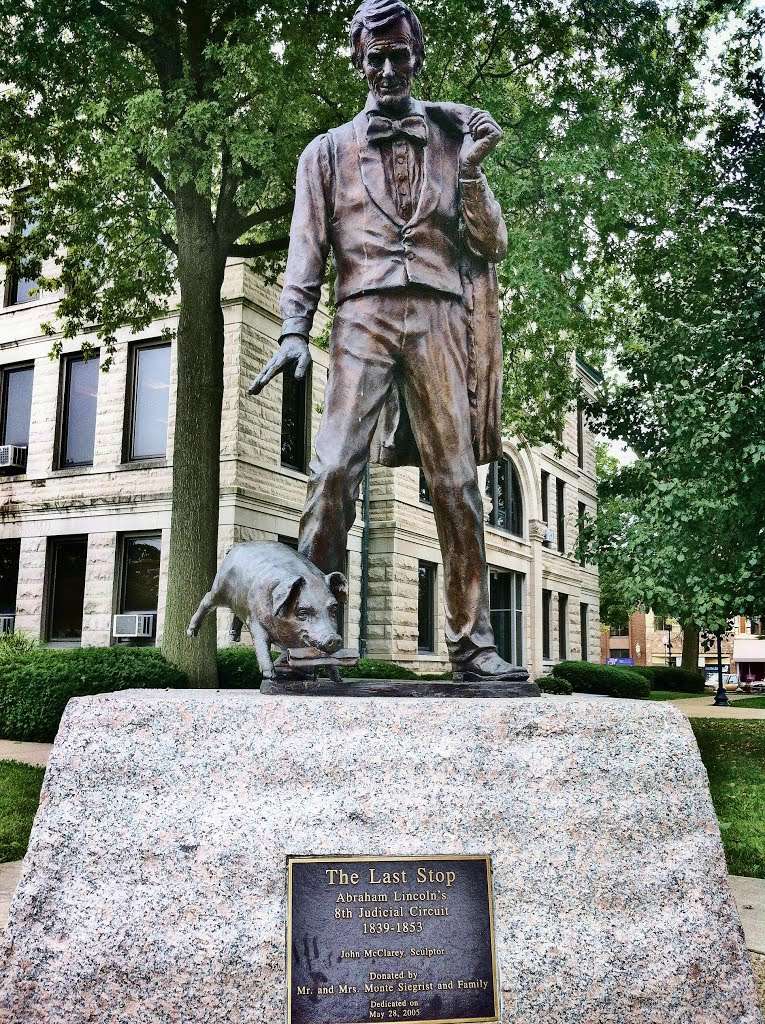

On March 1 I visited Springfield Illinois while working on an ongoing book project. My wife Rhonda wanted me out of the house for a couple of days for heavy spring cleaning. So I took advantage of an opportunity to visit some of the places I had long wished to visit but never seemed to get to. I visited a few of the markers on Lincoln’s 400-mile 8th judicial court circuit that he regularly traveled as a young lawyer during the 1840s and 1850s. I visited the courthouse in Taylorsville, where Lincoln’s court proceedings were often interrupted by the sounds of squealing pigs rooting under the courthouse floor — once so loudly that Lincoln asked the judge for a “writ of quietus” to calm the commotion. As you might imagine, Illinois is full of interesting Lincoln sites off the beaten path.

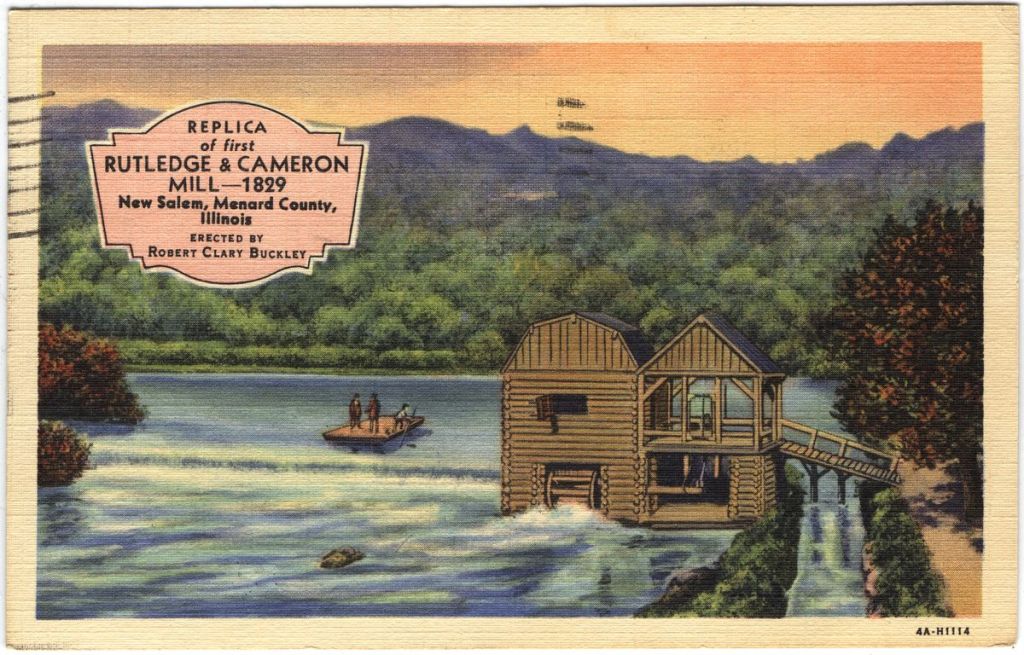

The place that I longed to see most was the final resting place of Abraham Lincoln’s first love, Ann Mayes Rutledge. She was born on January 7, 1813, near Henderson, Kentucky, the third of ten children born to Mary Ann Miller Rutledge and James Rutledge. In 1829, her father moved to Illinois and became one of the founders of New Salem, a community located 21 miles northwest of Springfield.

James Rutledge built a dam, sawmill, and gristmill in New Salem and is credited with laying out the town and selling the first lots of land there. In time, he converted his home into a tavern and inn where Ann worked — eventually, she took over the family business. Allegedly, Ann was the first (some say the only) girl to attend New Salem School. She was described as physically beautiful, 5 feet, 3 inches tall, 120 pounds with auburn hair, blue eyes, and a fair complexion. Her attitude was always positive, described as sweet and angelic, beloved by all who knew her. Her schoolteacher, Mentor Graham, described her as beautiful, amiable, kind, and an exceptionally good scholar. In 1832, young Abraham Lincoln boarded at the Rutledge Inn, where he got to know her.

While historians may disagree on the depth of her relationship with the rail splitter, there is no doubt that Ann Rutledge knew Abraham Lincoln. Ann died before the invention of photography, so no photos of her exist and no contemporary drawings of her have ever been found. Little in the way of verifiable data survives about Ann. Most of the details of her life were collected by Lincoln’s law partner of 17 years, former Springfield Mayor William Herndon. Billy was among the first to research those early years of Lincoln. While researching his book on Lincoln, Herndon retraced Lincoln’s tracks through central Illinois and southern Indiana. Billy Herndon did not care for Mary Lincoln and the feeling was mutual. So it comes as no surprise that Herndon was the first to push the relationship between Abraham and Ann.

Herndon’s details about Ann’s life came from people that knew Ann in New Salem, witnesses that historians have called “Herndon’s informants.” Rutledge neighbor James Short described Ann as “a good-looking, smart, lively girl, a good housekeeper, with a moderate education.” Likewise, Harvey Lee Ross, a boarder at the Rutledge family tavern in New Salem described Ann as “very handsome and attractive, as well as industrious and sweet-spirited. I seldom saw her when she was not engaged in some occupation – knitting, sewing, waiting on tables, etc…I think she did the sewing for the entire family. Lincoln was boarding at the tavern and fell deeply in love with Ann, and she was no less in love with him. They were engaged to be married, but they had been putting off the wedding for a while, as he wanted to accumulate a little more property and she wanted to go longer to school.” When interviewed by Herndon, Ann’s family testified that Lincoln was certainly smitten with Ann.

Not only was Lincoln attracted to Ann’s good looks, but he was also intrigued by her intelligence, a rare quality on the frontier. Herndon once said “I believe his very soul was wrapped up in that lovely girl. It was his first love – the holiest thing in life – the love that cannot die.” That all changed on August 25, 1835, when typhoid fever swept through New Salem and 22-year-old Ann Rutledge died. Legend states that Ann called Lincoln to her deathbed for a final goodbye before passing. Ann’s death unhinged Lincoln, leaving him severely depressed, a condition he would battle for the rest of his life. Upon her death, Lincoln confided to Mentor Graham that he felt like committing suicide, but Graham reassured him that “God has another purpose for you.” New Salem resident John Hill later said “Lincoln bore up under it very well until some days afterward when a heavy rain fell, which unnerved him.” Lincoln’s friend, Henry McHenry, testified that after Ann’s passing Lincoln “seemed quite changed, he seemed retired, & loved solitude, he seemed wrapped in profound thought, indifferent, to transpiring events.”

According to author Harvey Lee Ross in his book The Early Pioneers and Pioneer Events of the State of Illinois, Lincoln told friends: ‘My heart is buried in the grave with that dear girl. He would often go and sit by her grave and read a little pocket Testament he carried with him.” Another New Salem neighbor, Isaac Cogdal told Herndon that President-elect Lincoln confessed his love of Ann to him before leaving Springfield for Washington. “I did really – I ran off the track: it was my first. I loved the woman dearly & sacredly: she was a handsome girl – would have made a good loving wife – was natural and quite intellectual, though not highly educated…I did honestly – & truly love the girl & think often – often of her now.”

Ann was originally buried at the Old Concord graveyard (sometimes called Goodpasture graveyard) a pioneer cemetery located about seven miles northwest of New Salem. Some 200 people were buried there, many of whom knew Abraham and Ann personally. Today they stand as silent sentinels to the truthfulness of their courtship. Lincoln visited her gravesite frequently. According to Herndon, after Ann’s death, Lincoln “sorrowed and grieved, rambled over the hills and through the forests, day and night. He suffered and bore it for a while like a great man — a philosopher. He slept not, he ate not, joyed not. This he did until his body became emaciated and weak, and gave way. In his imagination he muttered words to her he loved … Love, future happiness, death, sorrow, grief, and pure and perfect despair, the want of sleep, the want of food, a cracked and aching heart, and intense thought, soon worked a partial wreck of body and of mind.”

To friends, Lincoln claimed that the thought of “the snows and rains fall(ing) upon her grave filled him with indescribable grief.” For days following her death, damp, stormy days, and gloomy weather triggered a deep depression that sent Lincoln to her gravesite where he lay prostrate over Ann’s grave. Lincoln’s behavior became so alarming that his friends sent him to the house of another kind friend, Bowlin Greene, who lived in a secluded spot hidden by the hills, a mile south of town. According to Herndon, “Here Lincoln remained for weeks under the care and ever-watchful eye of this noble friend, who gradually brought him back to reason or at least a realization of his true condition.” Yes, Abraham Lincoln knew Old Concord Graveyard well.

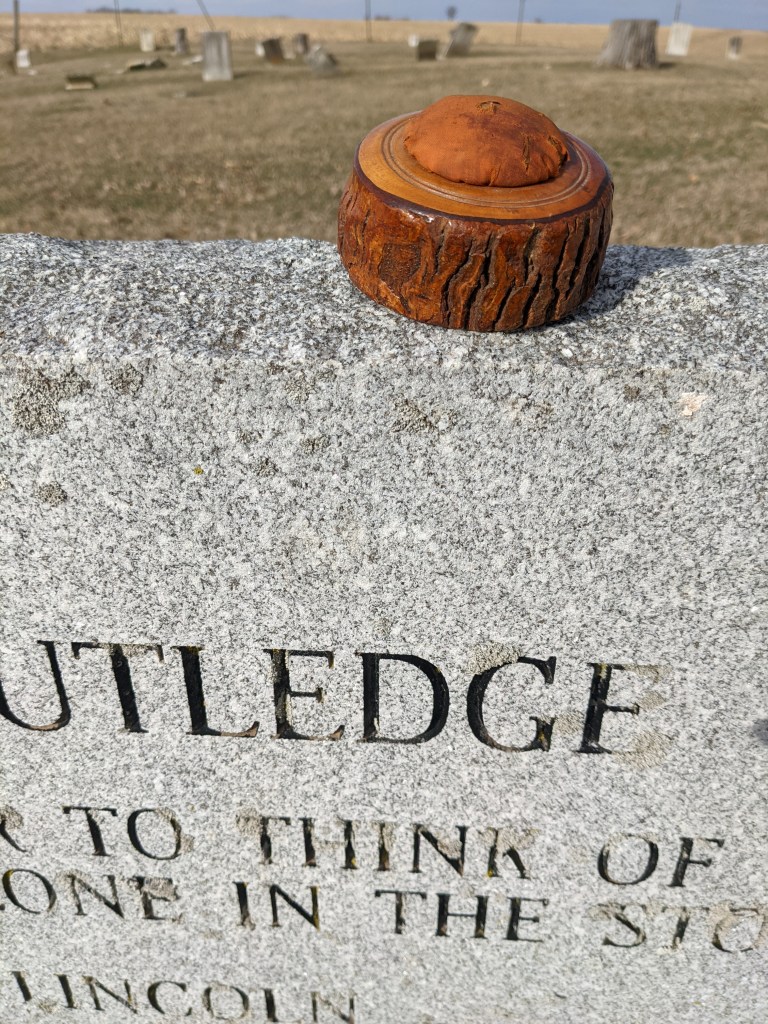

Here’s where the story takes a strange turn. Many years later, some enterprising citizens of nearby Petersburg, a town located four miles to the north, decided that Ann’s grave could help put their town on the map. Chief among them was Petersburg undertaker Samual Montgomery, ironically an elderly relative of Ann’s, and a cemetery promoter with the improbable name of D.M. Bone. These ad-hoc graverobbers decided it would be financially advantageous to move Rutledge’s remains for fear that their cemetery needed the draw of a famous name to compete with crosstown rival Rose Cemetery.

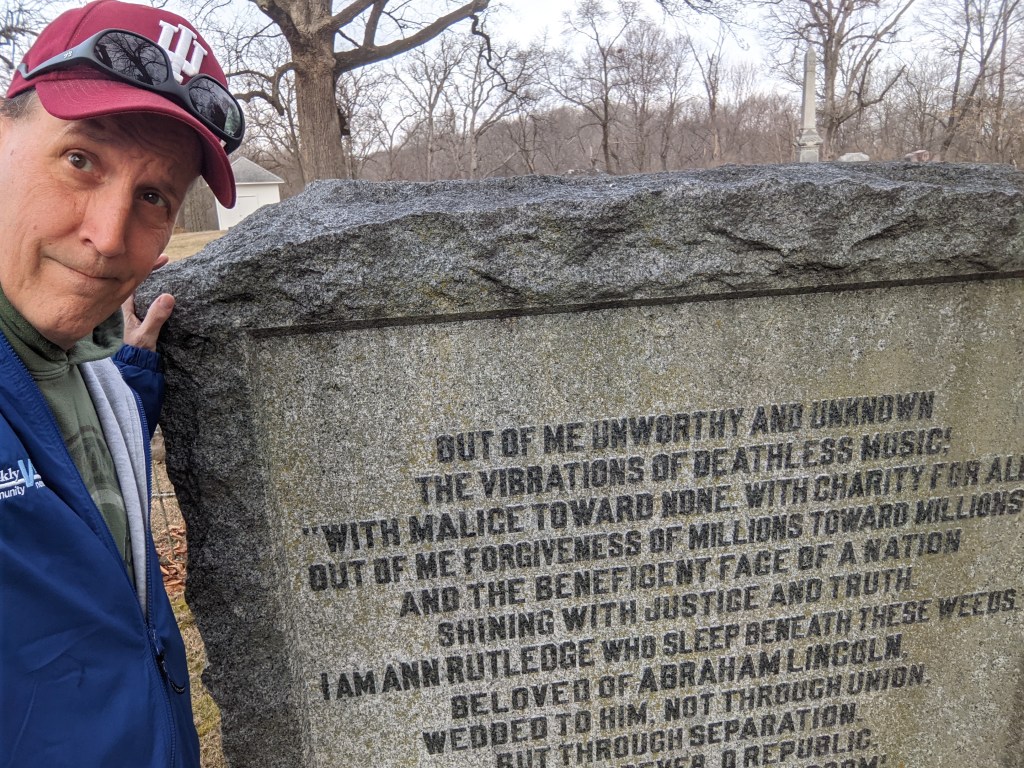

For three decades, all that marked Ann’s grave at the new cemetery was a rough stone with her name emblazoned in white letters on the front. In January 1921, Rutledge’s grave was fitted out with a magnificent granite monument inscribed with the text of the poem “Anne Rutledge,” from Edgar Lee Masters’s Spoon River Anthology. His words, engraved on her cenotaph at Oakland Cemetery are haunting: “I am Ann Rutledge who sleeps beneath these weeds, Beloved in life of Abraham Lincoln, Wedded to him, not through union, But through separation. Bloom forever, O Republic, From the dust of my bosom!” Regardless of the attempts by Lincoln biographers like Herndon, Ward Hill Lamon (Lincoln’s bodyguard), Carl Sandburg, and Indiana Senator Albert Beveridge to legitimize the Lincoln/Rutledge romance as fact, by the 1930-40s, Lincoln scholars expressed increased skepticism of the story. Most biographers agree that Lincoln and Rutledge were close, but several historians point to a lack of evidence of a love affair between them.

For my part, as a lifelong student of Lincoln, I choose it to be true. It is for that reason that I traveled to Petersburg, Illinois in search of Ann Rutledge’s grave. Finding Oakland Cemetery is an easy task and worth the visit. The massive granite marker is the most impressive memorial in the graveyard. Surrounded by an equally impressive wrought iron fence, the rough stone marker that originally graced her final resting place remains tucked away at the front of the plot although her name is slowly eroding away. Edgar Lee Masters’ epitaph is clear, legible, and easy to read. Master’s grave is only yards away. As impressive as the site may be, if you know the backstory, an overpowering soullessness pervades the spot simply because she is not there.

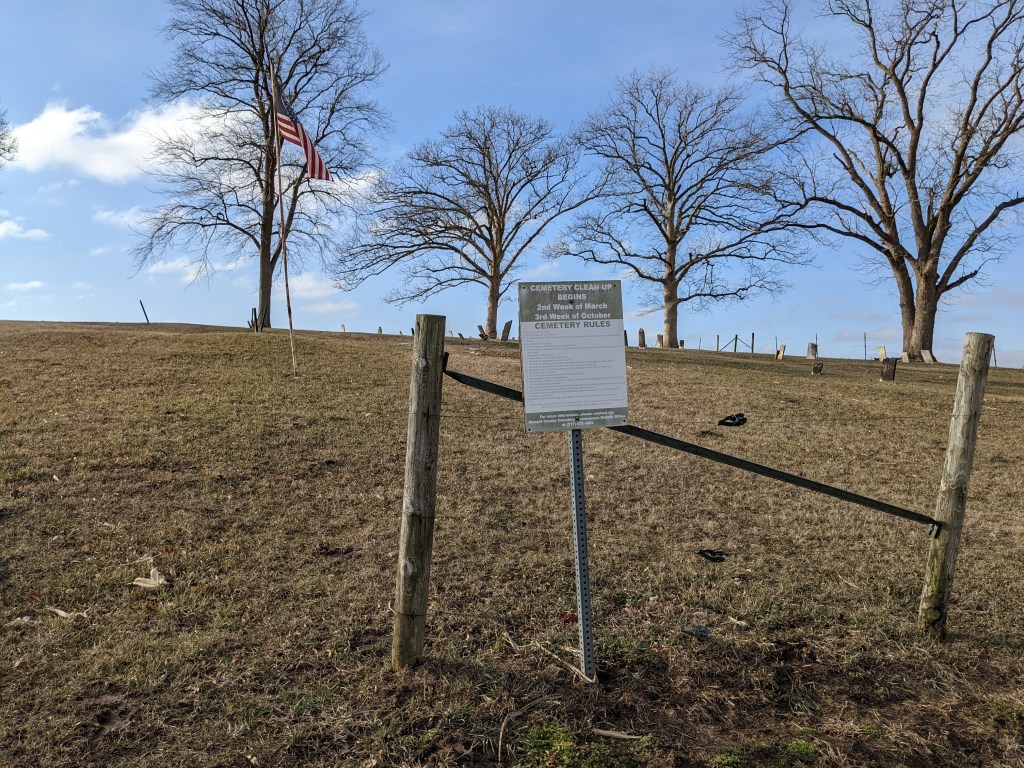

The place I really wanted to find was the Old Concord Graveyard. So I did what every stranger in a strange place does: I consulted Google maps. Oh, the navigator took me there, but just barely. The map directions led me to Route 97 North and the Lincoln Trail Road through the farm fields of Menard County, off the paved highway, and onto a gravel road. Like most midwestern roads, the winding serpentine roadways mimic the buffalo traces of centuries past. They wind through hills cut not by machinery, but by carts pulled by oxen and horses generations ago. Blind hills make the driver wonder if the road continues past each rise and dangerous curves make you tighten your grip on the steering wheel. Along the way, pheasants and quail stroll leisurely along the roadside. This is their domain and they fear no man out here.

Time and time again, my GPS ended in front of a brick farmhouse proclaiming “You have reached your destination.” This was not a cemetery, so I retraced my route, and five miles later, I found myself in the same spot. Finally, I pulled into the driveway and knocked on the door. My summons was answered by a friendly dog followed by a lovely mature woman. I threw myself upon the mercy of a stranger, apologized for the intrusion, and asked if this was the place. She smiled and said, “Well, you’re close” and led me to the side of the house where she pointed to the cemetery about a half mile in the distance.

She told me to head back out on the county road and keep turning left until I found an abandoned, dried-up waterway through a pair of cornfields. She said, “It is not really a road but the county crews still drive their equipment back there to keep the grass cut, so you should be able to find it,” The cemetery can not be seen from the gravel road, so it took me two passes to find it. When I did, I nervously went offroading about a quarter mile back upon a grassy lane between two cornfields. It had been raining before my arrival and rain was predicted for later that day, so I was less than confident that I could make it without getting stuck. Luckily, I arrived there safely.

The ancient graveyard is filled with veterans of the Revolutionary War like Robert Armstrong from North Carolina who died September 9th, 1834. Next to Robert is the marker of his son, Jack Armstrong of the Clary Grove gang, who famously fought Abe Lincoln to a draw in a wrestling match in New Salem. The battle became the stuff of legend and ultimately got Lincoln inducted into the Wrestling Hall of Fame. It did nothing for Jack Armstrong though. He died in 1854 although his stone incorrectly lists the death date as 1857. Most of the stones have been laid down face up so that they may still be read. Many are broken and rest in pieces strewn about in this ancient burying ground. A flagpole stands guard with a tattered American flag that shows the scars of a constant battle with the rough winds of the Illinois plains.

Ann’s grave rests on top of the hill next to that of her father, whose body was not removed to the new cemetery. Also near Ann is the grave of her brother David who died in 1842, a decade after serving with Abraham Lincoln in the Black Hawk War. There are many Rutledges still resting here. It is likely that most, if not all of them, were known by Ann or she by them. From Ann’s grave, I could look over my shoulder and see the farmhouse where I started. I wonder to myself what it would be like to live so close to such a magical place. Talking with the lady she told me they had been living there for 30 years. They had directed a few travelers like me to the spot, but not many. She informed me that her home was built by the Grosbaugh family and that it would have been there in 1835 when Ann drew Lincoln there. She pointed to an ancient natural stone step in the sideyard between her house and the graveyard and stated, “This was the watering trough and buggy turnaround, the start of a path that used to lead directly to the cemetery. It hasn’t been used in over a century.”

I’ve chased Lincoln all over this country. I’m sure I have stepped in his footprints many times. This spot, the Old Concord Cemetery, is the toughest Lincoln site I have ever found. It is impossible to find on your own and no map will lead you here. Here young Abraham Lincoln came day after day to mourn over his lost love. Here he lay upon her grave from autumn to winter, protecting her because he could not bear the thought of it raining or snowing upon her mortal remains. Today, a modern stone rests in Old Concord Graveyard on the spot that reads: “Original Grave of Ann Mayes Rutledge Jan. 7, 1813-August 25, 1835. Where Lincoln Wept.” Lincoln was here and here Ann remains. Her body literally melted into the soil of the central Illinois prairie. Here is the lone individual spot where anyone may visit to experience the raw emotion that was Abraham Lincoln.

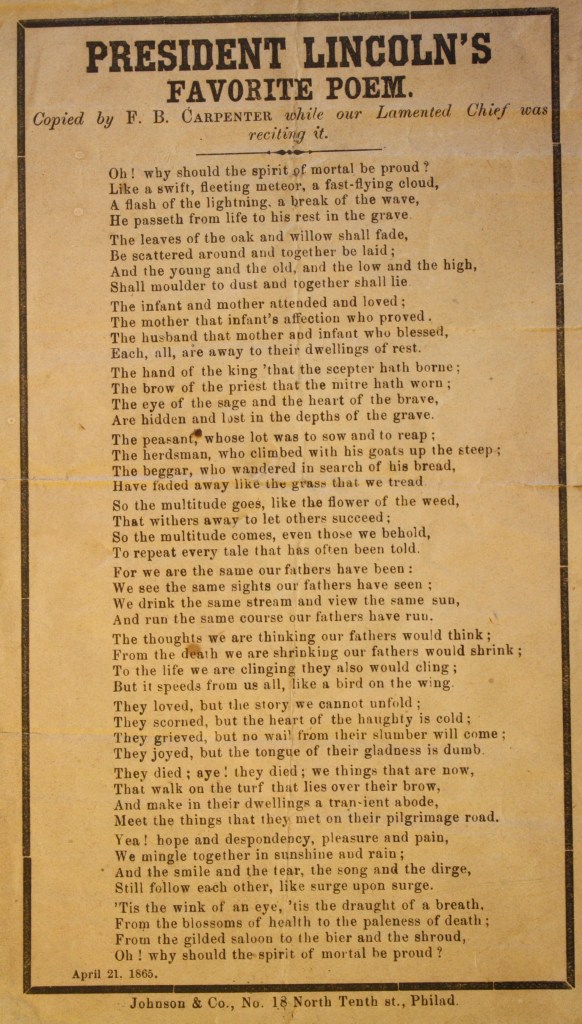

Abraham Lincoln’s Favorite Poem.

Original publish date October 19, 2023. https://weeklyview.net/2023/10/19/abraham-lincolns-favorite-poem/

During the month of October in Irvington, I am near-constantly surrounded by reminders of the dead. While Irvington celebrates Halloween with little door-knocking ghosties and goblins gliding from door to door in search of treats, it does nothing to dispel the fact that Halloween revolves around the spirits of the dearly departed. I write often about Abraham Lincoln, but seldom about Lincoln and Halloween. I thought it might be a good time to examine a mysterious poem that fits the season and has often been referred to as Lincoln’s favorite.

Lincoln developed his lifelong love of poetry while a boy in Southern Indiana. Although by his own admission, Lincoln got his education “by littles” and the total time spent in a classroom by the young rail-splitter amounted to less than a year, he devoured the poetry found in the four school readers historians attribute to his early years in the Hoosier state. Many of those poems were about death. John Goldsmith’s 1766 poem, An Elegy On The Death Of A Mad Dog, Edgar Allan Poe’s 1845 poem The Raven, Oliver Wendell Holmes’ 1831 poem The Last Leaf, and Thomas Gray’s 1751 poem Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard. And of course, Lincoln’s love of William Shakespeare is widely known.

These poets in particular capture the gloomy, melancholic poetry of which Lincoln was so fond of as a young man. Lincoln, a capable amateur poet himself, memorized the poems he cherished, reciting them to friends and inserting them in conversations and speeches throughout his life. His favorite poem, which he recited so often that people suspected he was its author, was William Knox’s “Mortality,” alternately known as “O, Why should the Spirit of Mortal be Proud!” Lincoln often opined to friends (and at least once in a letter) that he, “would give all I am worth, and go in debt, to be able to write so fine a piece as I think that is.”

The poem was cut from a newspaper and given to Lincoln by Dr. Jason Duncan in New Salem, Illinois. At the time, its author was anonymous, and attribution was unknown. On at least a few occasions, having committed it to memory, Lincoln wrote the Mortality poem out longhand and sent it to friends, always noting that “I am not the author.” He would spend twenty years searching for the poet. Aptly for the season, one stormy night in the White House, Lincoln recited the poem for a small group of friends including a congressman, an army chaplain, and an actor, noting that the “poem was his constant companion” and that it crossed his mind whenever he sought “relief from his almost constant anxiety.”

When the group departed, Lincoln requested that his guests help to discover who had written it. “Its author has been greatly my benefactor, and I would be glad to name him when I speak of the poem…that I may treasure it as a memorial of a dear friend.” Union General James Grant Wilson (1832-1914) would ultimately inform the President that the poem was written by an obscure Scottish poet named William Knox (1789-1825). The poem was first published in his 1824 book Songs of Israel. After Lincoln’s death, the poem experienced a resurgence in popularity.

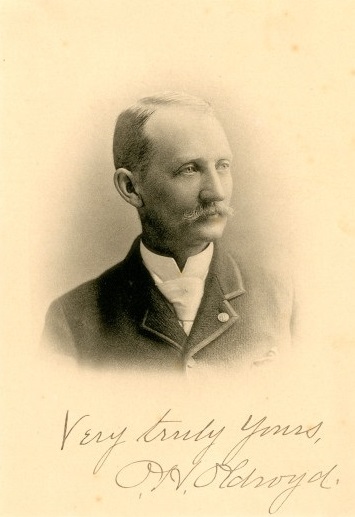

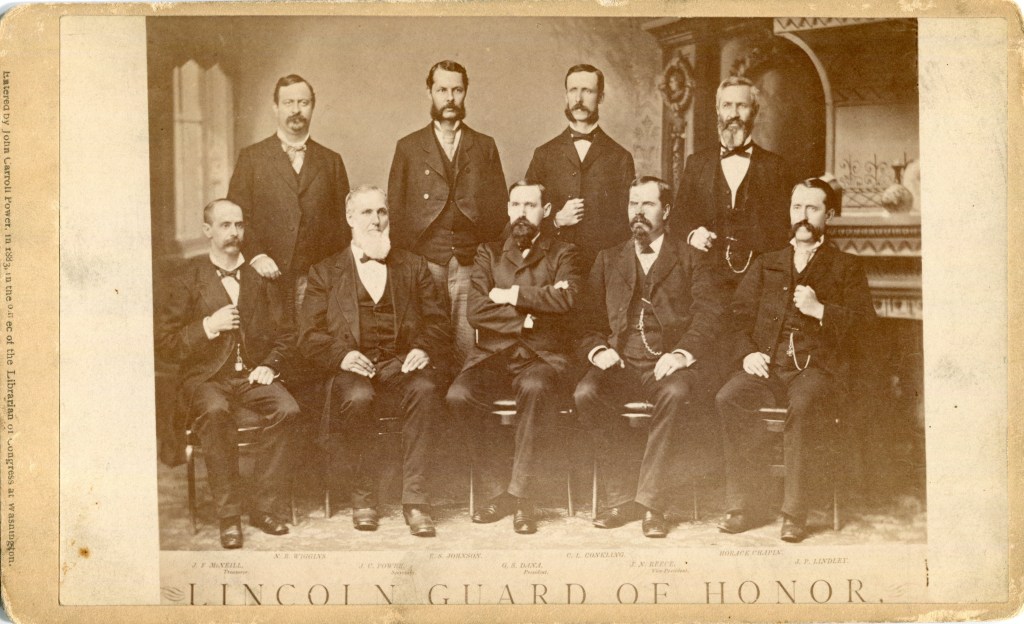

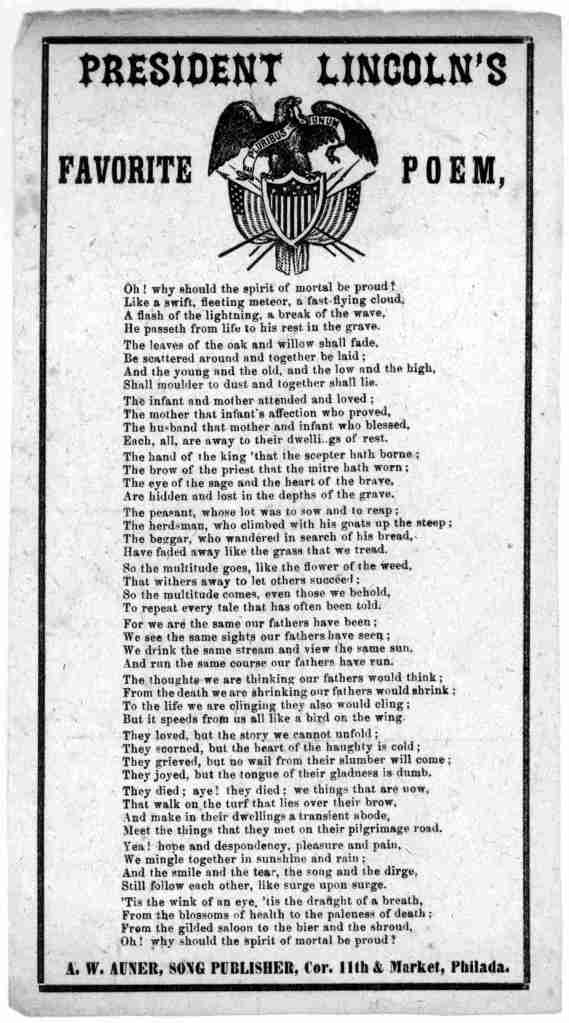

On April 15, 1880, on the 15th anniversary of the President’s death, the poem was read aloud by Mrs. Edward S. Johnson (wife of Lincoln Guard of Honor member and second Lincoln tomb custodian Major Edward S. Johnson) during a ceremony at the tomb in Springfield. A leaflet, handed out at that ceremony and found in my collection, was saved by Lincoln collector and personal muse Osborn H. Oldroyd and displayed in his collection in the Lincoln home for years. It remains important to the Oldroyd story as the impetus for his personal resolve to build a Lincoln Museum of his own.

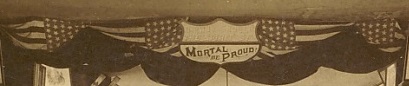

At that time the tomb’s Memorial Hall housed a small exhibit of Lincoln artifacts gathered by custodian John Carroll Power (a subject of my past columns). At that event, Oldroyd decided that his collection might be a bigger deal than he thought it was. “As I gazed on the…resting place of him whom I had learned to love in my boyhood years, I fell to wondering whether it might not be possible for me to contribute my might toward adding luster to the fame of this great product of American institutions,” wrote Oldroyd. It was after gazing upon those priceless Lincoln relics at the tomb that Oldroyd resolved to build a Memorial Hall in Springfield to display his own collection of Lincoln memorabilia. For a decade (1883 to 1893) that museum occupied the front parlors of the only home Abraham Lincoln ever owned at 8th and Jackson. The divider between those two rooms was adorned by a shield-shaped, flag-draped wooden motif adorned with the title “O, Why should the Spirit of Mortal be Proud!” Oldroyd made sure that every visitor to his museum was aware of the poem’s significance in the Lincoln chronology while surreptitiously causing each visitor to cast their eyes towards the heavens to receive the message.

The poem is written in Quatrain form with an A-A-B-B rhyme scheme, or clerihew, with all of the dominant words highlighted by the rhyme. The poem resounded in Lincoln’s mind like an echo, its pauses, and connotations framing the beat of the poem. The poem causes its reader to reflect on the inevitable continuity of life; Life is short so why sweat the small stuff? We are but insignificant players in a much grander scheme, so do all you can while you’re here. Here, submitted for your approval in the spirit of Halloween, is Abraham Lincoln’s favorite poem in its entirety.

“O why should the spirit of mortal be proud! Like a fast-flitting meteor, a fast-flying cloud, A flash of the lightning, a break of the wave-He passes from life to his rest in the grave. The leaves of the oak and the willow shall fade, Be scattered around and together be laid; As the young and the old, and the low and the high, Shall moulder to dust, and together shall lie. The child that a mother attended and loved, The mother that infant’s affection that proved, The husband that mother and infant that blest, Each-all are away to their dwelling of rest. The maid on whose cheek, on whose brow, in whose eye, Shone beauty and pleasure-her triumphs are by: And the memory of those that beloved her and praised, And alike from the minds of the living erased. The hand of the king that the sceptre hath borne, The brow of the priest that the mitre hath worn, The eye of the sage, and the heart of the brave, Are hidden and lost in the depths of the grave.”

“The peasant whose lot was to sow and to reap, The herdsman who climbed with his goats to the steep, The beggar that wandered in search of his bread, Have faded away like the grass that we tread. The saint that enjoyed the communion of Heaven, The sinner that dared to remain unforgiven, The wise and the foolish, the guilty and just, Have quietly mingled their bones in the dust. So the multitude goes-like the flower and the weed, That wither away to let others succeed; So the multitude comes-even those we behold, To repeat every tale that hath often been told. For we are the same things that our fathers have been, We see the same sights that our fathers have seen, We drink the same stream, and we feel the same sun, And we run the same course that our fathers have run.”

“The thoughts we are thinking our fathers would think, From the death we are shrinking from they too would shrink, To the life we are clinging to, they too would cling-But it speeds from the earth like a bird on the wing. They loved-but their story we cannot unfold; They scorned-but the heart of the haughty is cold; They grieved-but no wail from their slumbers may come; They joyed-but the voice of their gladness is dumb. They died-ay, they died! and we, things that are now, Who walk on the turf that lies over their brow, Who make in their dwellings a transient abode, Meet the changes they met on their pilgrimage road. Yea, hope and despondence, and pleasure and pain, Are mingled together like sunshine and rain: And the smile and the tear, and the song and the dirge, Still follow each other like surge upon surge. ‘Tis the twink of an eye, ’tis the draught of a breath, From the blossom of health to the paleness of death, From the gilded saloon to the bier and the shroud-O why should the spirit of mortal be proud!”

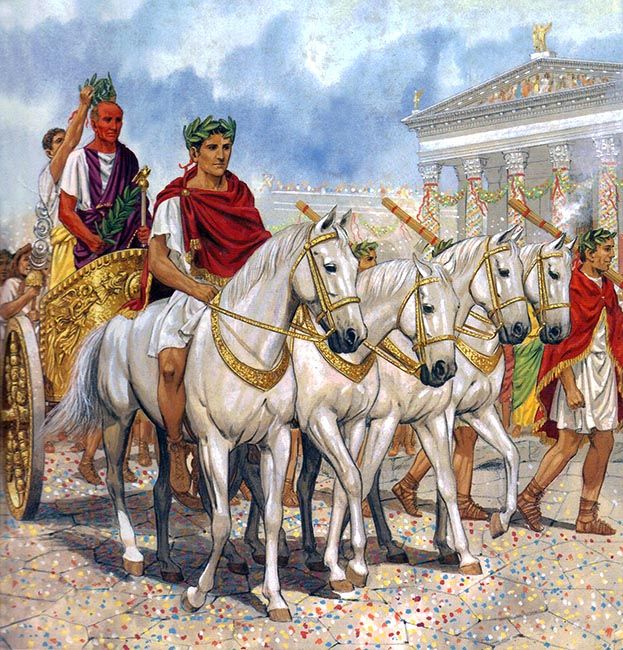

So what is the takeaway? Why should you be so proud of what you have, when all you have is so little in the bigger picture? The theme is one of life and death. A bleak and somber contrast reminds us that life is short, and in Lincoln’s case, fame is fleeting. Auriga, the slave charged with accompanying Roman Generals and Emperors through the streets of Rome after triumph in battle, often whispered the phrase Memento homo (remember you are only a man) while holding the golden crown inches above their heads. From a young age, Lincoln was well acquainted with the idea of mortality. So it comes as no surprise that he adored that poem. But it isn’t all gloom and doom. Within its stanzas are found muted messages of hope and the promise that it is not too late for society to change its ways by following in the footsteps of our ancestors. Reading this poem, one experiences the same feeling of reflection as Lincoln did. It explains how, during his entire lifetime, The Great Emancipator remained penitent and humble by simply following the lessons of this poem.