Category: Travel

Immigration, Baseball, PTSD, and the Titanic.

Original Publish Date October 2, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/10/02/immigration-baseball-ptsd-and-the-titanic/

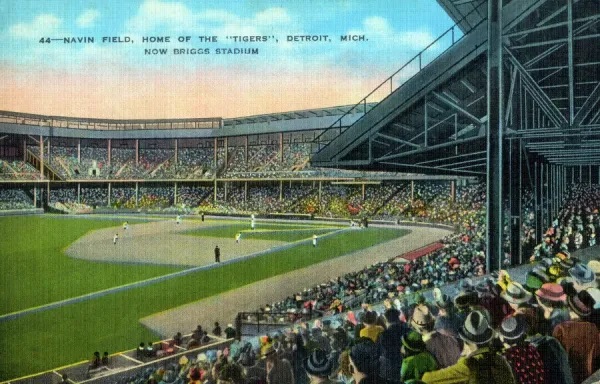

It’s playoff time in Major League Baseball. Right now, there are 12 teams marching toward the World Series. One of those teams, the Detroit Tigers, is heading to the playoffs for the second year in a row following a decade-long drought. The Tigers are one of the most storied franchises in MLB history. Since they became a major league franchise in 1901, the Tigers have won four World Series championships, 11 AL pennants, and four AL Central division championships. From 1912 to 1937, the Tigers played their home games at Navin Field in the Corktown neighborhood of Detroit. Corktown is a traditionally Irish settlement named so because nearly half of its settlers traced their lineage to County Cork, Ireland. Corktown is the oldest neighborhood in Detroit.

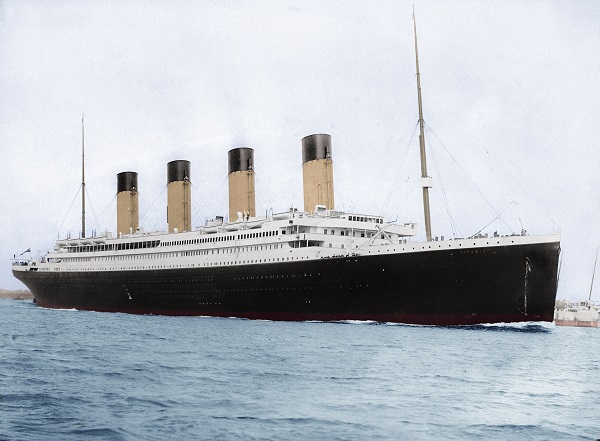

In 1911, the new Tigers owner Frank Navin ordered a new steel-and-concrete baseball park to be built that could seat 23,000 fans. Navin Field opened on April 20, 1912, the same day as the Red Soxs’ Fenway Park in Boston and just 5 days after the RMS Titanic sank. Another ominous portent is the fact that Cleveland Naps player “Shoeless” Joe Jackson scored the first run at Navin Field. Jackson was later banned from baseball as a member of the Chicago “Black Sox” team, accused of throwing the 1919 World Series. The $300,000 price tag for Navin Field translates to about $50 million today. The ballpark featured a 125-foot flagpole in center field that, to this day, is the tallest obstacle ever built in fair territory in a major league park. 26,000 fans crammed into the park for Navin Field’s opening day, postponed two days from its planned inaugural date because of rain. Despite that Motor City milestone, most of the attention was knocked from newspaper headlines the next morning by the sinking of the Titanic.

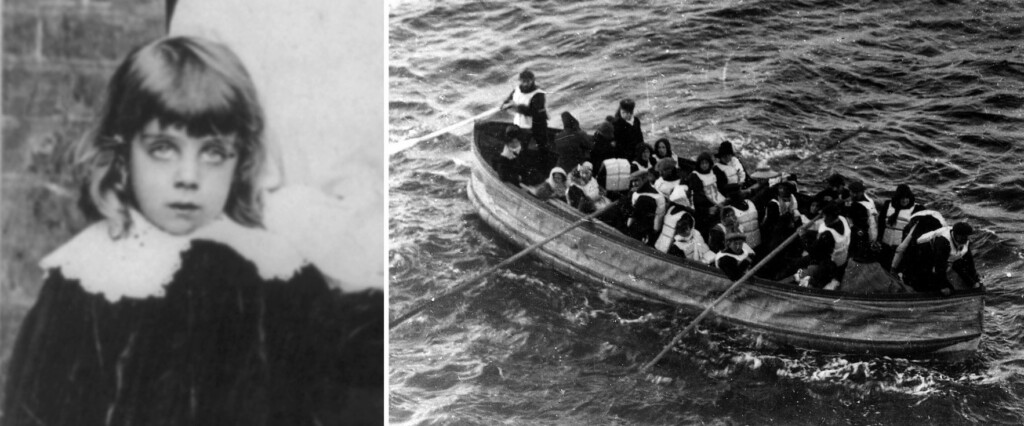

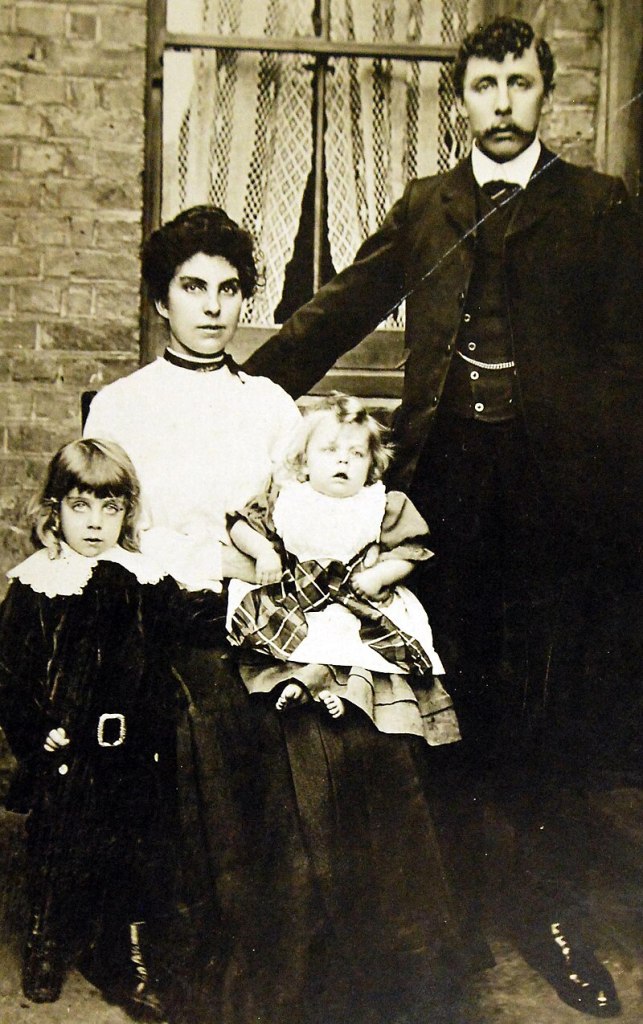

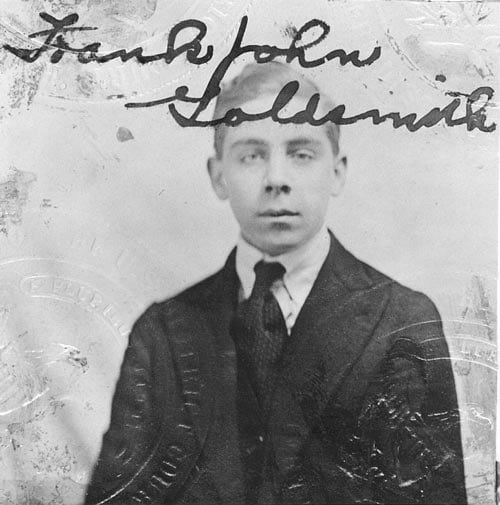

The week before that milestone grand opening day, some 3,700 miles away, a nine-year-old British boy named Frank John William Goldsmith was preparing for the trip of a lifetime. Frankie was born in Strood, Kent, England, the eldest child of Frank and Emily Goldsmith. Between 1908 to 1911, most of the extended Goldsmith family emigrated to the US, settling in Detroit. In the spring of 1912, Frankie’s parents decided to join them. The Goldsmith family boarded the New York City-bound RMS Titanic in Southampton as third-class passengers. During the first three uneventful days aboard ship, Frankie spent his time playing and exploring the ship with other similarly aged English-speaking third-class children. The boys ran the decks, climbed the baggage cranes, and wandered down to the boiler rooms to watch the stokers and firemen at work. Of these boys, only Frankie and one other survived the sinking.

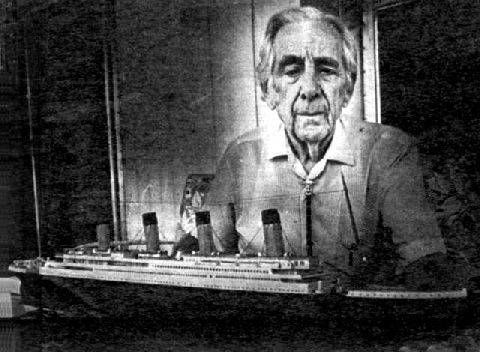

Unsurprisingly, Goldsmith (1902-1982) remembered the exact moment his personal Titanic trauma began for the rest of his life. In a speech to the Rotary Club in 1977, he recalled that he was lacing up his shoes in his third-class passenger cabin when a Titanic officer knocked on, and then opened, the cabin door at about 1:30 a.m. The officer pointed to the ceiling and informed them to put on one of the lifejackets located there. Earlier, Frankie’s father woke his family and informed them to get dressed and prepare to make their way up to the prow of the ship. Ironically, Frankie’s family likely made their way up from their cramped F-deck third-class quarters via the opulent Grand Staircase of the ship. Upon learning that the “Unsinkable Titanic” had struck an iceberg, the family made their way to the forward end of the boat deck, where the “Collapsible C” lifeboat was being loaded. Frankie remembered the lifeboat being surrounded by a ring of crewmen who were only letting women and children on. Collapsible C was the second to last ship to leave, carrying 41 passengers and departing at 1:47 a.m.

Goldsmith wrote of the experience: “Mother and I then were permitted through the gateway. My dad reached down and patted me on the shoulder and said, ‘So long, Frankie, I’ll see you later.’ He didn’t, and he may have known he wouldn’t.” Goldsmith Sr. died in the sinking; his body was never recovered. Goldsmith wrote a book about his Titanic experience, published posthumously by the Titanic Historical Society in 1991. That book, Echoes in the Night: Memories of a Titanic Survivor, remains the only full account recorded by a third-class passenger.

As their lifeboat floundered in the Atlantic Ocean, to keep her son’s young mind off the unfolding tragedy, Frankie’s mother instructed him to turn his back to the sinking ship and care for an invalid survivor. For forty agonizing minutes, the screams of the doomed passengers echoed across the water. By 2:20 a.m, the RMS Titanic was totally submerged, but helpless survivors lasted another 10 minutes before surrendering to the icy waters. The ship sank two hours and 40 minutes after impact with the iceberg. Collapsible C was picked up by the RMS Carpathia around 6:30 a.m. During those four anguished hours asea, Mrs. Goldsmith busied herself sewing clothes from blankets for women and children who had left the ship in only nightclothes. After being rescued, young Frankie was initiated by RMS Carpathia’s boiler-stokers as an honorary seaman by having him drink a mixture of water, vinegar, and a whole raw egg. Frankie swallowed it in one gulp, and from then on, he proudly considered himself a member of the ship’s crew. Nine-year-old Goldsmith remembered the crewmen telling him, “Don’t cry, Frankie, your dad will probably be in New York before you are.”

Growing up, Goldsmith clung to the hope of his father’s survival. It took him months to understand that his dad was really dead, and for years afterward, he dreamed that “another ship must have picked him up and one day he will come walking right through that door and say, ‘Hello, Frankie.’” Alas, he never saw his father again. Throughout Goldsmith’s life the Titanic became both a dream and a nightmare. At times, he would suddenly start talking uncontrollably about that midnight, how he grabbed some candy when leaving their cabin; how, as his descending lifeboat passed a porthole, he saw teen-age crew members playing hide and seek; how the Titanic shot off rockets as if it were the King’s birthday. An adolescent memory of his lifeboat rowing hard after the receding lights of a foreign fishing boat, fleeing the disaster lest its illegal presence become known. The endless, anxious nail-biting sick-feeling of survivor’s guilt that never goes away.

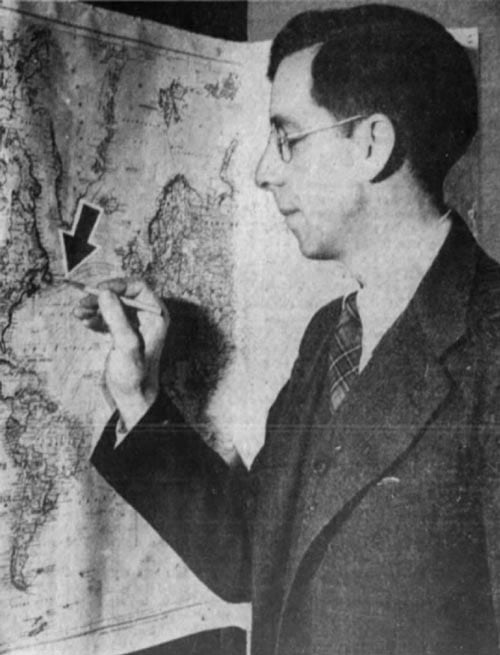

Upon arrival in New York City, Frankie and his mother were cared for by the Salvation Army, which provided train fare to reach their relatives in Detroit. They moved to a home near the newly opened Navin Field, home of the Detroit Tigers. However, unlike most 9-year-old boys, Frankie was never a big fan of baseball. Within easy earshot of the new ballyard, every time Frankie heard the crowd erupt in cheers during a game, he cringed. The sound reminded him of the screams of the dying passengers and crew in the water just after the ship sank; as a result, he never attended Tigers baseball games. Although the acronym PTSD is a more recent generational term, it is nonetheless real. Post-traumatic stress disorder exists as a mental health condition caused by an extremely stressful or terrifying event. PTSD can be caused by either being a part of it or by witnessing it. PTSD may include flashbacks, nightmares, severe anxiety, and uncontrollable thoughts about the event. Nearly everyone knows someone who has suffered from, or continues to battle against, the mysterious (often undiagnosed) condition. It can be a combat war veteran friend who avoids July 4th celebrations or a family member who avoids hospitals due to the loss of a loved one to cancer or another devastating disease. The point is, as I’ve always preached, history matters, and many of the daily hardships we face today have been outlined by our ancestors.

Frankie married Victoria Agnes Lawrence (Goldsmith) in 1926, and they had three sons: James, Charles, and Frank II. During World War II, Frankie served as a civilian photographer for the U.S. Army Air Corps. After the war, he brought his family to Ashland, Ohio, and later opened a photography supply store in nearby Mansfield. Goldsmith died at his home in 1982, at age 79. His ashes were scattered over the North Atlantic, above the site where the Titanic rests.

Frank John William Goldsmith Jr. was just another immigrant child when he survived the tragic sinking of the Titanic. For the remainder of his life, the fatherless boy could never enjoy the cheers of a crowd, regardless of the occasion. Every loud exuberant roar transported him back to that dark April night in 1912. To Frankie, the sound echoed the screams and cries of passengers fighting for their lives in the icy Atlantic. Goldsmith carried the weight of that association with him for the rest of his life. So my friends, when you encounter a neighbor, a friend, a relative, or an immigrant, remember you take them as you find them. Their story might run a little deeper than you think.

The Devils Tower.

Original publish date: September 23, 2021. https://weeklyview.net/2021/09/23/the-devils-tower/

https://www.digitalindy.org/digital/collection/twv/id/4308/rec/153

Over the last couple of weeks, I detailed a long-lost Indiana landmark known as the Hoosier Slide in Michigan City. This giant mound of sand became a tourist attraction when visitors discovered that they could slide down its slopes on slices of cardboard or fragments of cloth like a sled on a snow mound. The Hoosier Slide disappeared from the northern Indiana landscape around World War I after it was purchased by the Ball Brothers Corporation in Muncie to furnish the distinctive blue tint for their popular Ball Brand fruit jars.

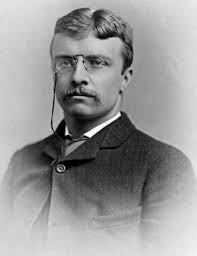

Continuing that theme, it was 115 years ago this week (Sept. 24, 1906) that President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed Devils Tower in Wyoming as the nation’s first National Monument, under new authority granted to him by Congress in the Antiquities Act. The Antiquities Act resulted from concerns about protecting mostly prehistoric Native American ruins and artifacts (aka “antiquities”) located on federal lands. The United States Congress designated the area a U.S. forest reserve in 1892. However, in the ensuing years, the threat of commercial development and the removal of artifacts from these unprotected lands by private collectors, whom Teddy famously referred to as “pot hunters,” had become a serious problem. Making this a high-priority goal for Teddy’s second term.

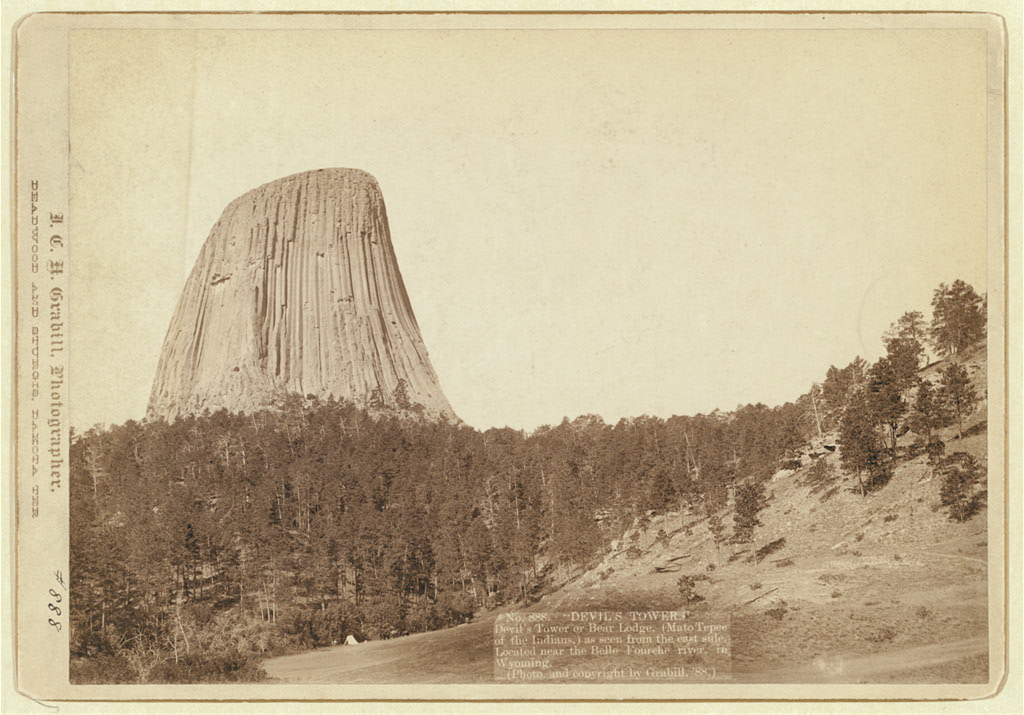

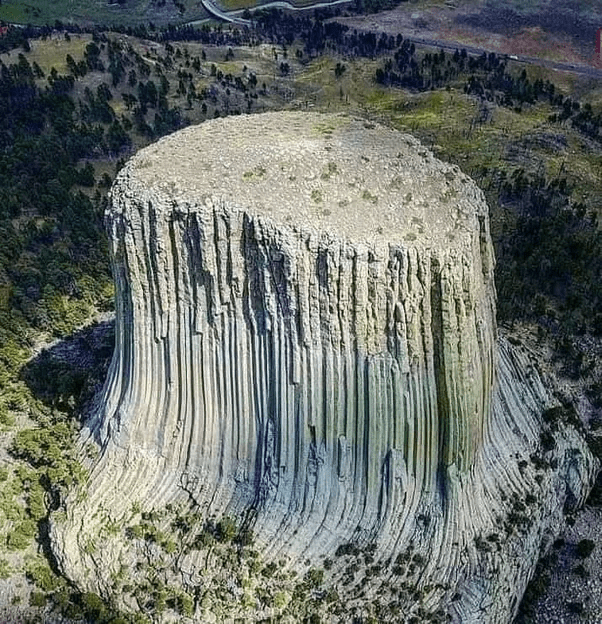

Although Devils Tower (apostrophe purposely omitted) might not ring any bells in your house, it was so important to Roosevelt that he designated it for protection before he established the Grand Canyon Game Preserve by proclamation on November 28, 1906, and the Grand Canyon National Monument on January 11, 1908. Devils Tower, also called Bear Lodge Butte, is part of the Black Hills mountain range located above the Belle Fourche River near Hulett and Sundance in Crook County, northeastern Wyoming. The tower, technically called a “monolith”, was formed from cooled magma exposed through erosion. It stands 1,267 feet tall; 867 feet from summit to base (5,112 feet above sea level) and encloses an area of 1,347 acres.

The oldest rocks visible in Devils Tower National Monument were once part of a shallow sea during the Triassic period 250 million years ago, which saw the rise of reptiles and the first dinosaurs. Devils Tower hails from the Jurassic period, about 200 million years ago, which ushered in birds and mammals. The Tower was here 150 million years before the Rocky Mountains and the Black Hills were formed. It is easy to imagine that the thought of dinosaurs roaming around Devils Tower may well have sparked Teddy Roosevelt’s vivid imagination, thus leading him to designate it as the country’s first National Landmark.

Fur trappers may have visited Devils Tower, but they left no written evidence of having done so. The first documented Caucasian visitors were members of Captain William F. Raynolds’s 1859 expedition to Yellowstone. Sixteen years later, Colonel Richard I. Dodge escorted a US Government Office of Indian Affairs scientific survey party to the massive rock formation and coined the name Devils Tower. The misnomer was created when his interpreter reportedly misinterpreted a native name to mean “Bad God’s Tower”. The Indigenous Native American people had many names for the outcropping including Bear’s House, Grizzly Bear Lodge, Bear’s Tipi, Home of the Bear, Bear’s Lair, Tree Rock, Great Gray Horn, and Brown Buffalo Horn.

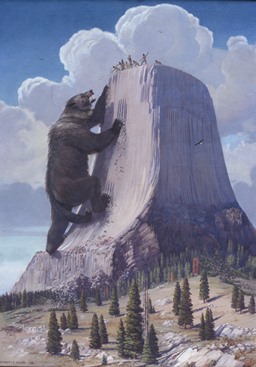

According to the lore of the Lakota tribe, the traditional name for the tower came after a group of girls went out to play and were spotted by several giant bears, who began to chase them. In an effort to escape the bears, the girls climbed atop a rock, fell to their knees, and prayed to the Great Spirit to save them. Hearing their prayers, the Great Spirit made the rock rise from the ground towards the heavens so that the bears could not reach the girls. The bears, in an effort to climb the rock, left deep claw marks in the sides, which had become too steep to climb. Those are the marks that appear today on the sides of Devils Tower. When the girls reached the sky, they were turned into the star formation known as the “Seven Sisters.”

Another version tells that two Kiowa Sioux boys wandered far from their village when Mato the bear, a huge creature that had claws the size of teepee poles, spotted them and wanted to eat them for breakfast. He was almost upon them when the boys prayed to Wakan Tanka the Creator to help them. They rose up on a huge rock, while Mato tried to get up from every side, leaving huge scratch marks as he did. Finally, he sauntered off, disappointed, discouraged, and hungry. The bear came to rest east of the Black Hills at what is now Bear Butte. Wanblee, the eagle, helped the boys off the rock and back to their village. A painting depicting this legend by artist Herbert A. Collins hangs over the fireplace in the visitor’s center at Devils Tower.

In a Cheyenne version of the story, the giant bear pursues the girls and kills most of them. Two sisters escape back to their home with the bear still tracking them. They tell two boys that the bear can only be killed with an arrow shot through the underside of its foot. The boys have the sisters lead the bear to Devils Tower and trick it into thinking they have climbed the rock. The boys attempt to shoot the bear through the foot while it repeatedly attempts to climb up and slides back down leaving more claw marks each time. The bear was finally scared off when an arrow came very close to its left foot. This last arrow continued to go up and never came down.

Wooden Leg, a Northern Cheyenne, related still another legend told to him by an old man as they were traveling together past the Devils Tower around 1866. A Native American man decided to sleep at the base of Bear Lodge. In the morning he found that he had been transported to the top of the rock by the Great Medicine with no way down. He spent another day and night on the rock with no food or water. After he had prayed all day and then gone to sleep, he awoke to find that the Great Medicine had brought him back down to the ground. Devils Tower is still considered to be sacred ground which has caused distress among the Native American tribes who described the Devils Tower designation as offensive. However, the name was never changed.

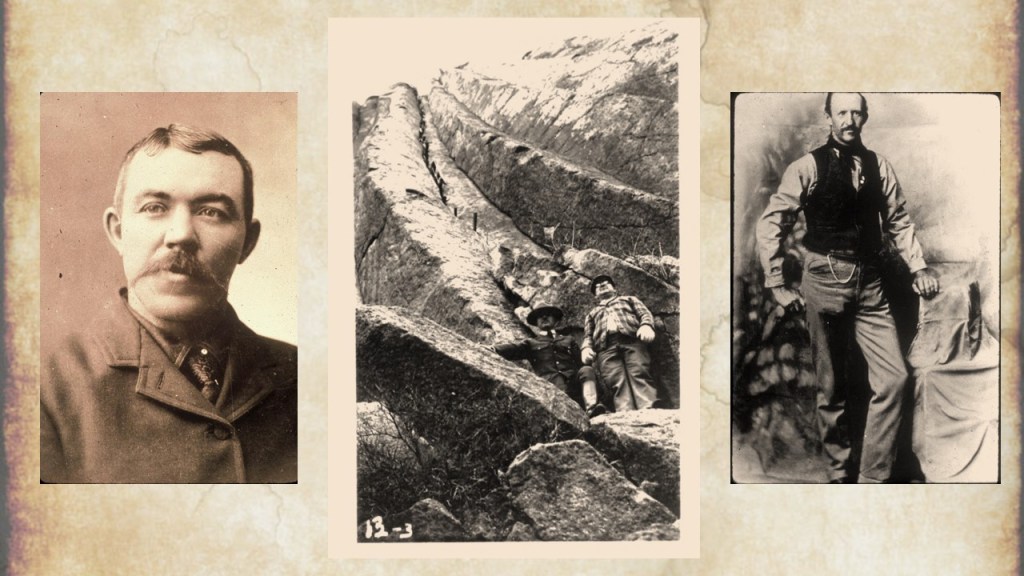

In recent years, climbing Devils Tower is on many a bucket list. The first known ascent of Devils Tower occurred on July 4, 1893. It is credited to a pair of local ranchers, William Rogers and Willard Ripley. They completed this first ascent after constructing a ladder of wooden pegs driven into cracks in the rock face. About 1,000 people came from up to 12 miles away to witness this first formal ascent of the tower. Rogers’ wife Linnie ascended the ladder two years later, becoming the first woman to reach the summit of the tower. An estimated 215 people later ascended the tower using Rogers’ ladder. It was last used in 1927 by stunt climber Babe (”the Human Fly”) White, a roaring twenties daredevil who climbed skyscrapers all over the country for publicity.

Rogers and Ripley’s climb jump-started a sport climbing industry at the tower that continues to the present day. Over thirty years, the ladder, located on the southeast side of Devils Tower, fell into disrepair. Today, what remains of the ladder begins about 100 feet above the ground and ascends from there to the summit. Sources vary on the original length of the ladder, some accounts say it was 350 feet while others say 270 feet. In the 1930s, the decision was made to remove the lower 100 feet of the ladder for safety reasons. The ladder can still be seen from the trails around the monument.

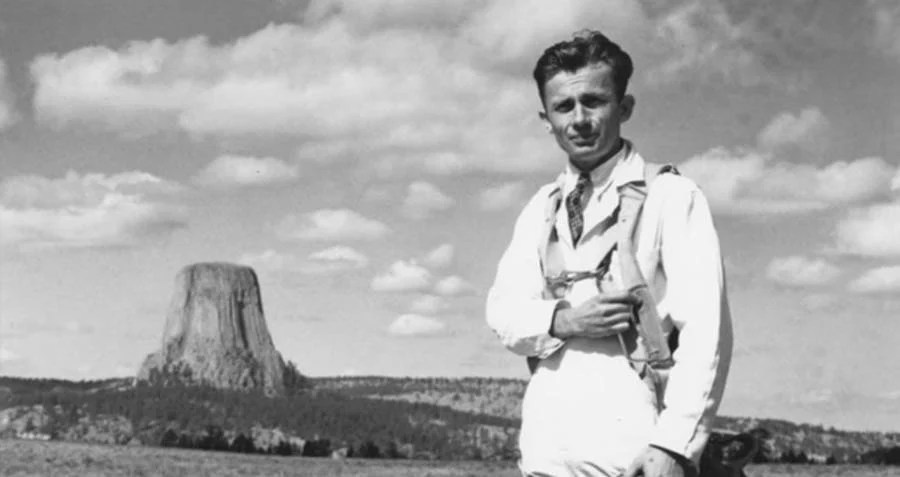

In 1941, Devils Tower became front-page news. Daredevil George Hopkins parachuted onto Devils Tower to settle a bet. His intention was to repel down the slope via a 1,000-foot rope dropped to him after a successful landing on the butte. To Hopkins’ horror, the package containing the rope, a sledgehammer, and a car axle to be driven into the rock as an anchor piton for the rope. As the weather deteriorated, a second attempt was made to drop equipment, but the rope froze in the rain and wind and could not be used. Hopkins was stranded for six days, exposed to frigid temperatures, freezing rain, and 50 mph winds before a mountain rescue team reached him and brought him down.

Today, hundreds of climbers scale the sheer rock walls of Devils Tower via climbing routes covering every side of the prehistoric landmark. All of them must check in with a park ranger before and after attempting a climb. No overnight camping at the summit is allowed; climbers return to base on the same day they ascend. Because the Tower is sacred to several Plains tribes, including the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Kiowa, many Native American leaders objected to climbers ascending the monument, considering this to be a desecration. Because of this, a compromise was reached with a voluntary climbing ban during the month of June when the tribes are conducting ceremonies around the monument.

The tower has a flat top covering 1.5 acres and its fluted sides give it an otherworldly appearance. Its color is mainly light gray and buff. Lichens cover parts of the tower, and sage, moss, and grass grow on its top. Chipmunks and birds live on the summit, and a pine forest covers the surrounding countrysides below. Additionally, Devils Tower National Monument protects many species of wildlife, such as white-tailed deer, bald eagles, and prairie dogs, the latter of which maintain a sizeable population at the base of the monument.

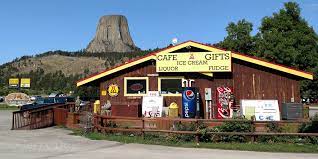

All of this is well and good and obviously, had the Hoosier slide been likewise protected, we may still be sliding down the massive sand dune in northern Indiana today. But movie buffs everywhere recognize Devils Tower for another reason. The 1977 movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind used the formation as the bellwether of its climactic scene. It soon became the film’s trademark logo. Its release caused a large increase in visitors and climbers to the monument. Today, the otherworldly pull and Hollywood fame of Devils Tower has made it a cultural waymark.

With the funds from the film’s creation, the owners of the surrounding land were able to open a campground and restaurant to host climbers, sightseeing fans of the landscape, and movie buffs. Campers are welcome to hike and climb the tower twenty-four hours a day, and at night they’re treated to a showing of Close Encounters on a screen at the base of the landmark. According to the brochure, “Visitors leave with a new appreciation for the unique rock formation and a deepened curiosity about our place in space.”

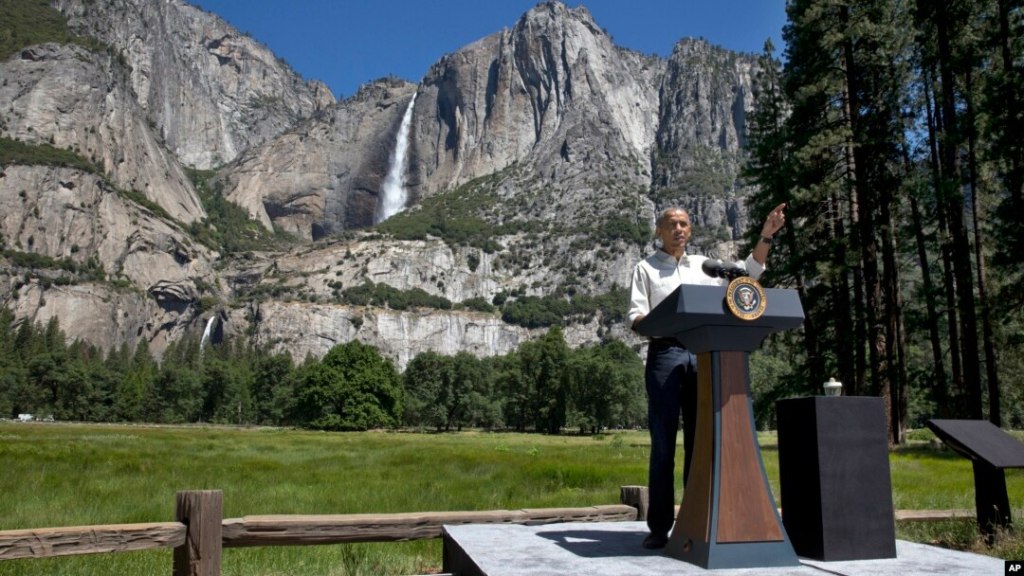

And, for an added “new appreciation”, although Teddy Roosevelt is considered to be the “father” of the National Park System, you might be interested to learn that during his two terms, President Obama established more monuments than any President before him with 26, breaking the previous record held by President Theodore Roosevelt who had 18. In short, on both accounts, it was a bi-partisan land grab for the good.

A Gift from a Friend. Abraham Lincoln, Art Sieving, and the Long Nine Museum.

Original publish date October 3, 2024. https://weeklyview.net/2024/10/03/a-gift-from-a-friend/

Rhonda and I strolled through Irvington last week to reconnect with some old friends. We visited Ethel Winslow, my long-suffering editor at the Weekly View, and then stopped in to see Jan and Michelle at the Magick Candle. From there we went down to see Dale Harkins at the Irving and then popped into Hampton Designs to check in with Adam. After that, we tried (in vain) to track down Dawn Briggs for a stop-and-chat, then traveled over to see Randy and Terri Patee for a 3-hour porch talk over a fine cigar. Why do I retrace our visit with you? Simply because I hope that anyone reading this article either is, or will, make a similar stroll through the Irvington neighborhood this Fall season and visit their old haunts as well.

I am blessed to know these folks and every one of them has been kind, giving, and thoughtful to us over the years, particularly lately as Rhonda has faced some difficult health challenges. The gals at the Magick Candle have gifted me treasures over the years connected to the people and places they know I love (Disney’s Haunted Mansion and Abraham Lincoln come to mind), the Patees have given me relics from the pages of history, and yesterday, Adam stopped me in my tracks by stating, “Wait, Carter found something for you.” Adam fumbled around gracefully behind the counter before finding the object of his search. As he handed it to me, I felt certain that he believed it to be just another Lincoln item, but I knew immediately what it was.

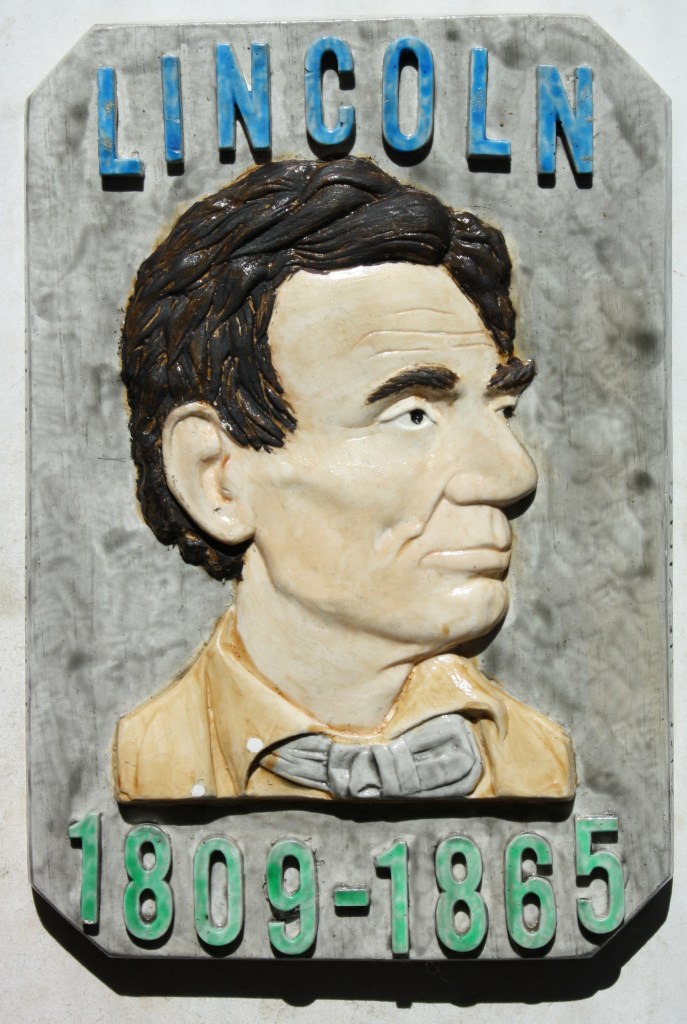

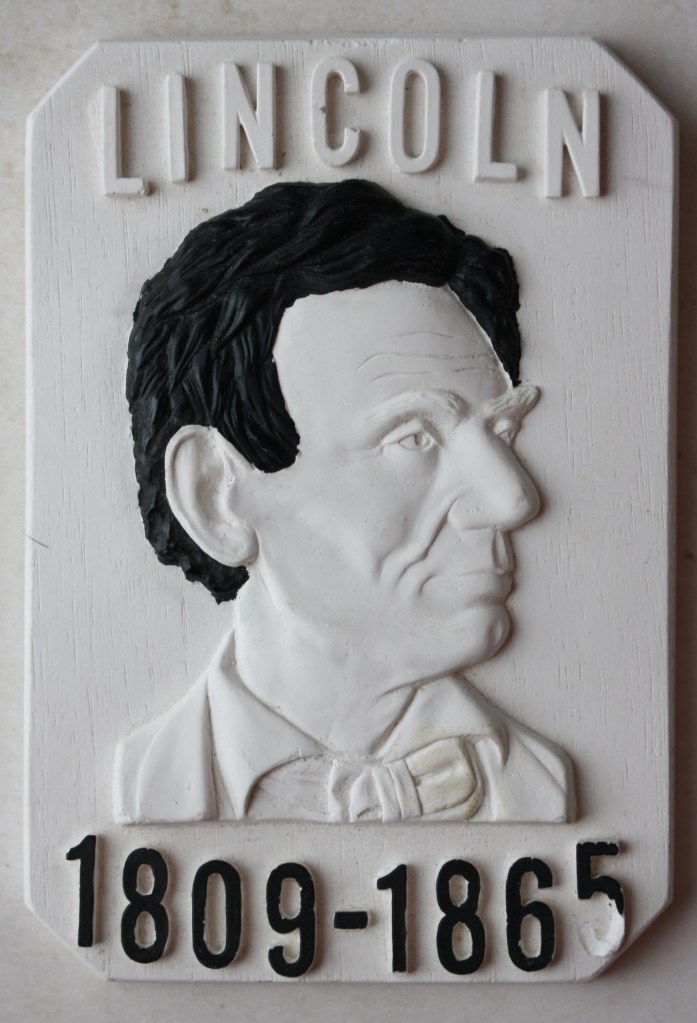

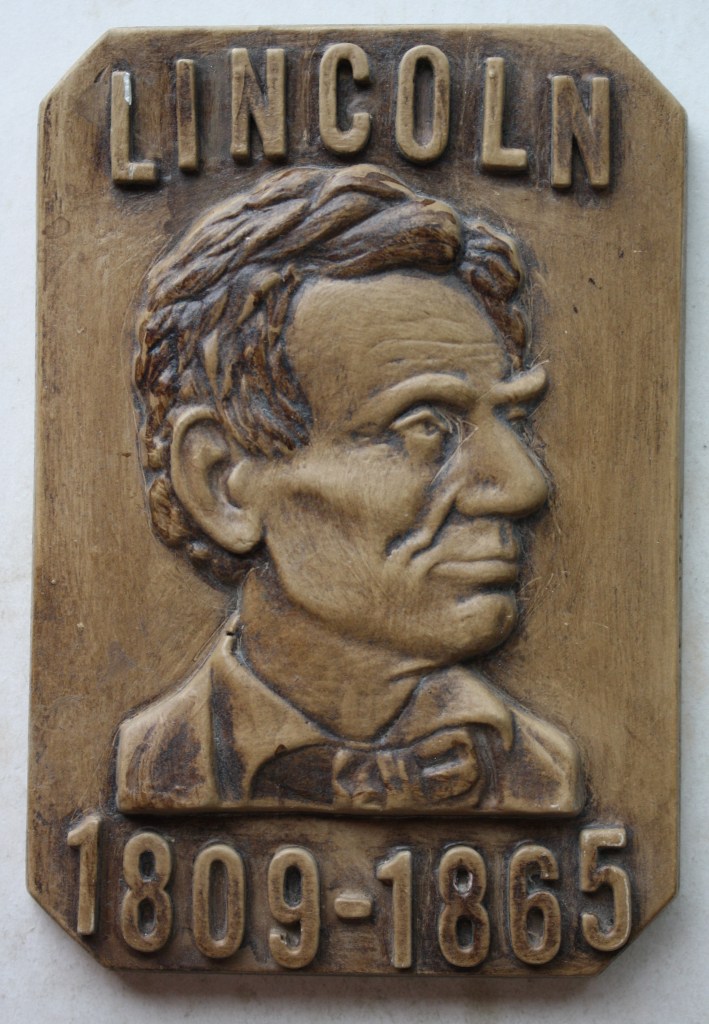

The object is a ceramic plaque about the size of a paperback novel picturing a young, beardless Abraham Lincoln with his birth and death dates inset in raised / relief lettering on the front. It is painted in bright Victorian Era colors that teeter on the edge of being gaudy but are always irresistibly attractive. Rhonda was standing by my side (as always) and when I showed it to her she oohed and aahed at it simply because she understands what such things mean to me. When I told her that it had a secret surprise attached to it, she looked closer at it. Knowing what was in store, I turned the plaque sideways in my hand to reveal the artist’s name, Art Sieving, on the right edge and then turned it over to the left edge to show the town name of Athens, Illinois. Since she has listened patiently to my historical ramblings for 35 years now, she wisely responded, “Oh, the Long Nine Museum.” Ding, ding, ding, we have a winner!

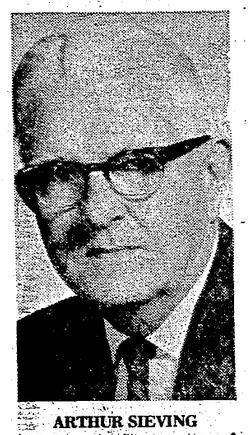

Carter and Adam had no idea, since, unlike me, they have lives outside of history books and museums, but with this gift, they had hit me in my sweet spot. I knew what it was because I already have a version, but mine, while still interesting to me, is a bland matte-finish version that pales in comparison to this one. These plaques were created by Arthur George Sieving (1902-1974) from Springfield, Ill. He was a wood carver, magician, sculptor, and ventriloquist who created many fine architectural carvings, clocks, and ventriloquist figures. At the time of his death, Art was working on the diorama displays at the Long Nine Museum in Athens. He is buried in Springfield’s Oak Ridge Cemetery final resting place of Abraham Lincoln. I was introduced, unknowingly, to Sieving’s work when, many years ago, I purchased a stunning metallic gold plaque depicting the Abraham Lincoln Tomb. About the size of a college diploma, like Carter’s plaque, it depicts the Tomb in a raised/relief style so realistically that it casts its own shadow depending on the lighting.

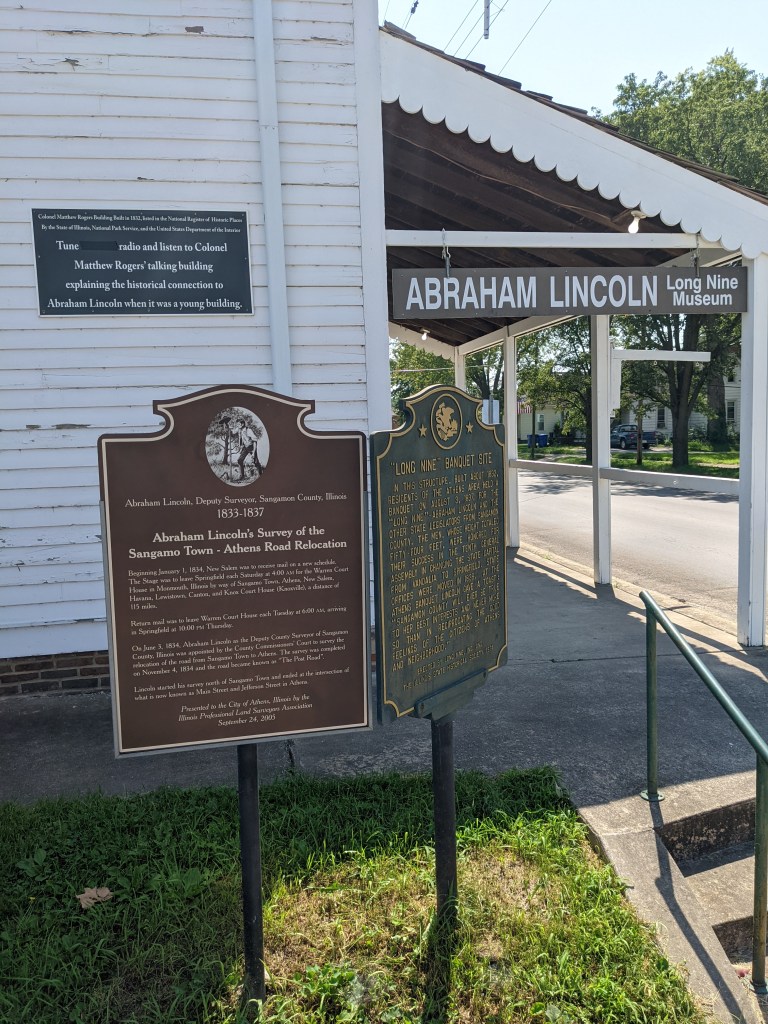

I had no idea who created the piece until I traveled to Athens (Pronounced Ay-thens) just a stone’s throw north of Springfield. I ventured there to meet with Jim Siberell, curator of the Long Nine Museum, who travels from his home in Portsmouth, Ohio during the summertime months to keep the museum open. Jim and I share a mentor in Dr. Wayne C. “Doc” Temple, the subject of my upcoming biography. As Mr. Siberell toured me through the museum, I spotted the exact plaque on display there. Of course, I asked for the history and Jim explained the artist’s connection to the museum. For those of you unaware, the Long Nine building is an important waymark of Illinois history. It was in this building, on the second floor, where Abraham Lincoln and six other state legislators (two of the members did not attend) decided to move the Illinois state capitol from Vandalia (near St. Louis) to the more centralized location of Springfield.

In 1837, a dinner party was held in the banquet room on the second floor to honor those legislators who were effective in passing a bill to relocate the capital. They earned the sobriquet of “The Long Nine” because together their height totaled 54 feet, each man being over 6′ tall or taller. Among the attendees was Abraham Lincoln, who at age twenty-seven was the youngest of the group. Lincoln gave the evening’s toast by saying, “Sangamon County will ever be true to her best interest and never more so than in reciprocating the good feeling of the citizens of Athens and neighborhood.” What this Hoosier finds most interesting is that when the delegates carved out the boundaries of Sangamon County, the home of the new state capitol, they left Athens out. Athens became a part of Menard County as did their neighbor, Lincoln’s New Salem.

Mr. Siberell toured me through the building and explained how Art Seiving had created the dioramas in the museum that recounted the stories of the men of The Long Nine in hand-carved wooden miniature displays. Each diorama’s characters were created by Seiving and the backgrounds were painted by artist, Lloyd Ostendorf. Siberell escorted me up the original stairway to the second-floor banquet room which features a stunning, massive oil painting by the late artist Lloyd Ostendorf showing Lincoln in formal dress toasting his colleagues. The mural covers an entire wall and is set against a table arranged much the same as it would have been on that fateful night. The visitor stands upon the original flooring of the banquet room where Lincoln gave his famous toast. The history room downstairs is a researcher’s dream. It contains many copies of Lincoln’s handwritten letters, documents from the history and restoration of the building, newspapers from the era, and historic photos. A trip to the basement reveals the building’s original fireplace, an arrray of period artifacts, and a scale model of Lincoln’s Tomb so big that it required the construction of a special pit to accommodate its massive size.

The March 23, 1973, Jacksonville (Illinois) Journal Courier reported. “Seiving has been working hard since January making the “Lincoln Head” plaques in his basement. He used a rubber mold taken from a carving…he pours into it the powdered molding material and fashions a Lincoln head of great exactness and beauty. During the past weeks, he has made enough of them to fill every available space in his basement. When he makes a few hundred more they will be delivered to a central point for use in Athens; he will then start on larger statues. The plaques being furnished are in white plaster material, but will be finished into a walnut appearance with a high polish and most attractive “feel” and “look”.

The article continues, “The classic dioramas made by Art Seiving will present all of those documented events which presented Lincoln in Athens, including hand-carved wooden figures, utensils, tools, buildings, and animals carved from wood.” One of Art’s carvings was titled, “Lincoln goes to school in Indiana”…It takes two people (himself and his wife) three nights to cut out 800 little paper leaves, and it’s no short job, either, to glue them to the branches, one by one. Others have taken longer. Mr. Seiving was five or six days just putting in 3,000 “tufts” of grass in his last completed scene. The grass is frayed rope strands, cut and dried and then glued down…And while you’d swear that the miniature pots and pans were made of metal, in actuality, most are simply wrapping paper glued to metal rings.” Sieving stated that it took him five to seven days to carve each figure, and one diorama alone featured 11 figures. His preferred medium was walnut with augmentations of birch wood.

Seiving is described as an “internationally known magician, sculptor and ventriloquist” whose “dummy” partner was known as “Harry O’Shea.” Of course, Art carved all of the ventriloquist dummies used in his acts himself. Art’s magic act was called the “Art Seiving and his Art of Deceiving.” Aside from the Long Nine Museum, he is best known for his dioramas at the Illinois State Museum, ‘Model of New Salem Village’ and wood sculptures including the ‘Egyptian Motif Clock’. Seiving’s George Washington carving is in the Smithsonian Institution’s collection.

Art’s Lincoln plaques are by no means rare but cannot be classified as common in the “collectorsphere”. I believe the Long Nine Museum still has a few for sale if memory serves, and one would set you back about the cost of a Starbucks coffee nowadays. To me, the value is not a monetary one, but rather the story the item tells. The version that Carter discovered (and so kindly gifted to me) is signed “Love, Laurie” on the back, making it all the more special to me. I tend to love these little travel souvenirs from the 1960-70s. I’m a space race Bicentennial kid who enjoys discovering these little treasures. They represent a vacation, a trip, a moment in someone’s life. Usually a kid, they are never confined to age, race, or gender. I appreciate that, in this age where everything handmade seems to come from China, most of these old travel souvenirs originate from where they were being sold. At that moment, they were the most important thing in that person’s life. Hand-picked with a smile and a “wow” to be taken home and enjoyed long after the trip concluded. A physical manifestation of a cherished memory. So thank you “Laurie” whomever or wherever you are for saving this little treasure for a history nerd like me. And most importantly, thank you Carter for thinking of me.

George Alfred Townsend and The War Correspondent Memorial Arch.

Original publish date April 11, 2024. https://weeklyview.net/2024/04/11/george-alfred-townsend-and-the-war-correspondent-memorial-arch/

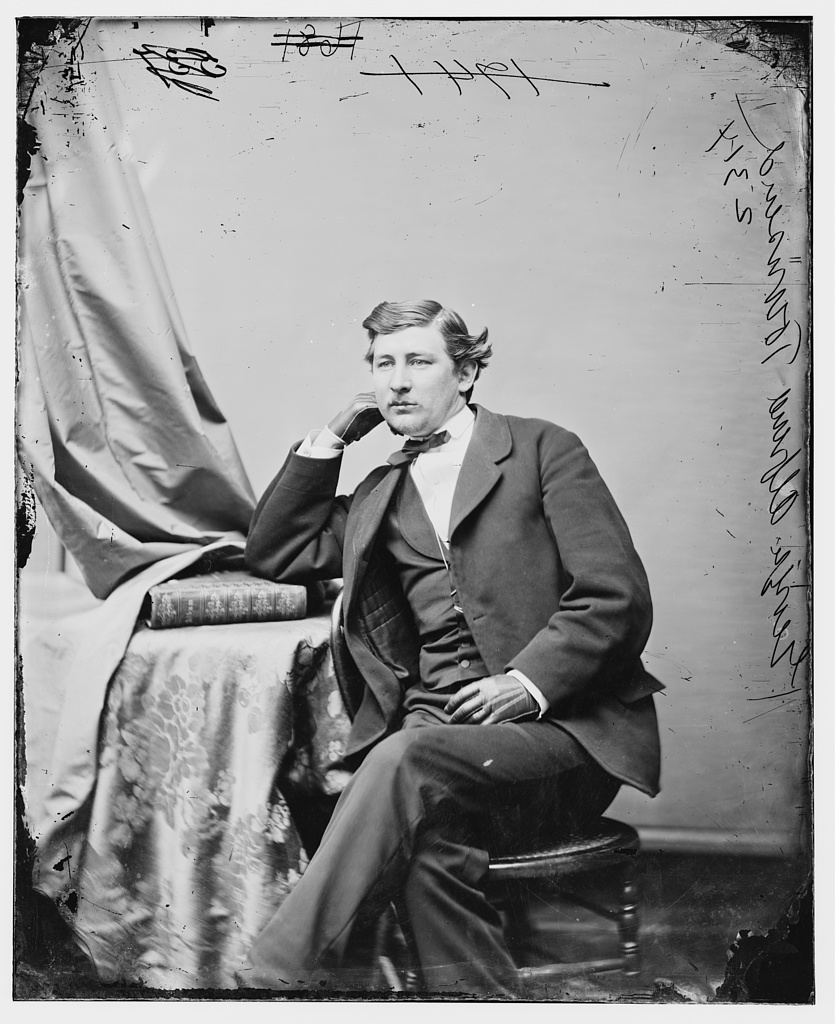

Next week will witness another sad passing in American history: the 159th anniversary of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Because I live with this date dancing around in my head more than most, I want to share my experience (and admiration) for a peripheral character in that tragedy: George Alfred Townsend. Born in Georgetown, Delaware on January 30, 1841, Townsend was one of the youngest war correspondents during the American Civil War. Soon after graduation from high school (with a Bachelor of Arts) in 1860, Townsend began his career as a news editor with The Philadelphia Inquirer. In 1861, he moved to the Philadelphia Press as city editor. As the war broke out, he worked for the New York Herald as a war correspondent in Philadelphia.

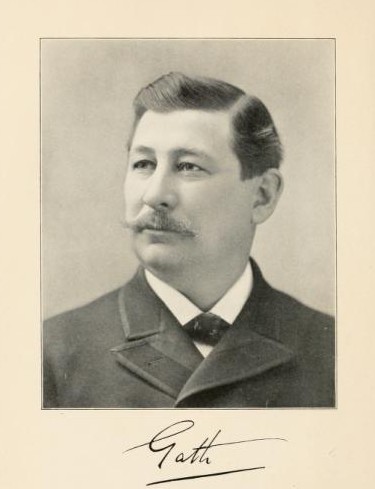

By April 1862, George got his big break when General George McClellan rode through Philadelphia on his way to Washington. That fortuitous meeting would propel young Townsend to exclusive access to many of the Civil War’s greatest battles. One of America’s first nationally syndicated columnists, Townsend used the pen name “Gath” for his newspaper columns. Gath was an acronym of his initials with the addition of an “H” at the end. Friends and contemporaries like Mark Twain, Bret Harte, and Noah Brooks, claimed the “H” stood for “Heaven” while wags and rivals claimed it stood for “Hell.” Gath himself was inspired by the biblical passage uttered by David after the death of King Saul in II Samuel 1:20, “Tell it not in Gath, publish it not in the streets of Askalon.”

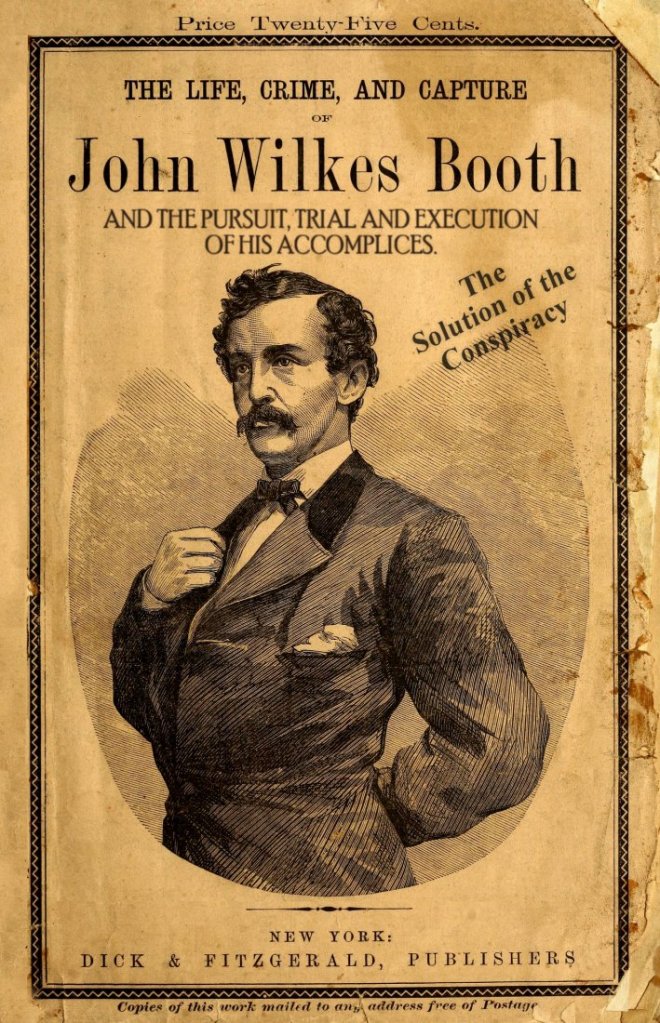

While Townsend won accolades for his work covering the war, it was his coverage of the Lincoln assassination that he is best remembered for. His detailed columns (which he called “letters”) about the tragedy were filed between April 17 – May 17 and would later be published as The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth. Published in 1865, Townsend’s book offers a full sketch of the assassin, the conspiracy, the pursuit, trial, and execution of his accomplices. As a lifelong student of Lincoln, I have read countless books, articles, letters, and various accounts centered on his life. It was in George Alfred Townsend’s “letters” that I found my holy Grail. Townsend’s description of Lincoln in his coffin made me feel as if I were standing there myself. His description of Lincoln’s office left me awestruck and wishful. In my opinion, it would be hard to find a more worthy example of Victorian journalism than these excerpts from Gath’s “letters”.

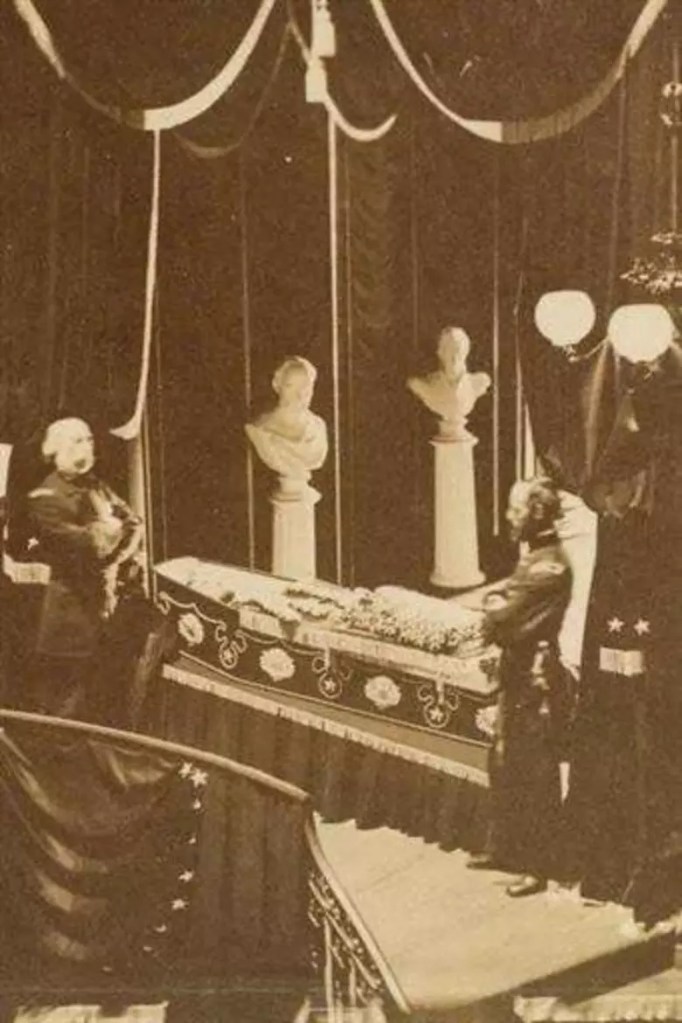

“Deeply ensconced in the white satin stuffing of his coffin, the President lies like one asleep. Death has fastened into his frozen face all the character and idiosyncrasy of life. He has not changed one line of his grave, grotesque countenance, nor smoothed out a single feature. The hue is rather bloodless and leaden; but he was always a sallow. The dark eyebrows seem abruptly arched; the beard, which will grow no more, is shaved close, save the tuft at the short small chin. The mouth is shut, like that of one who had put the foot down firm, and so are the eyes, which look as calm as slumber. The collar is short and awkward, turned over the stiff elastic cravat, and whatever energy or humor or tender gravity marked the living face is hardened into its pulseless outline. No corpse in the world is better prepared according to appearances. The white satin around it reflects sufficient light upon the face to show us that death is really there; but there are sweet roses and early magnolias, and the balmiest of lilies strewn around, as if the flowers had begun to bloom even upon his coffin. Looking on interruptedly! for there is no pressure, and henceforward the place will be thronged with gazers who will take from the site its suggestiveness and respect. Three years ago, when little Willie Lincoln died, Doctors Brown and Alexander, the embalmers or injectors, prepared his body so handsomely that the President had it twice disinterred to look upon it. The same men, in the same way, have made perpetual these beloved lineaments. There is now no blood in the body; it was drained by the jugular vein and sacredly preserved, and through a cutting on the inside of the thigh the empty blood vessels were charged with the chemical preparation which soon hardened to the consistence of stone. The long and bony body is now hard and stiff, so that beyond its present position it cannot be moved any more than the arms or legs of a statue. It has undergone many changes. The scalp has been removed, the brain taken out, the chest opened and the blood emptied. All that we see of Abraham Lincoln, so cunningly contemplated in his splendid coffin, is a mere shell, an effigy, a sculpture. He lies in sleep, but it is the sleep of marble. All that made the flesh vital, sentiment, and affectionate is gone forever.”

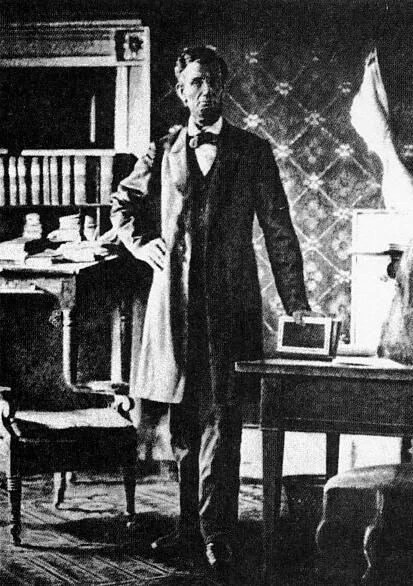

On May 14, 1865, the day Abraham Lincoln’s body was placed on the funeral train to leave Washington DC forever, Townsend visited the White House. Mary Lincoln still resided there with her beloved son Tad, too distraught to leave the White House. “I am sitting in the President’s office. He was here very lately, but he will not return to dispossess me of the high-backed chair he filled so long, nor resume his daily work at the table where I am writing. There are here only Major Hay (Salem Indiana’s John Hay, Lincoln’s private secretary) and the friend who accompanies me. A bright-faced boy runs in and out, darkly attired, so that his fob chain of gold is the only relief to his mourning garb. This is little Tad, the pet of the White House. That great death, with which the world rings, has made upon him only the light impression which all things make upon childhood. He will live to be a man pointed out everywhere, for his father’s sake; and as folks look at him, the tableau of the murder will seem to encircle him.”

Townsend further describes Lincoln’s office, just as he left it. “The room is long and high, and so thickly hung with maps that the color of the wall cannot be discerned. The President’s table at which I am seated adjoins a window at the farthest corner; and to the left of my chair as I reclined in it, there is a large table before an empty grate, around which there are many chairs, where the cabinet used to assemble. The carpet is trodden thin, and the brilliance of its dyes is lost. The furniture is of the formal cabinet class, stately and semi-comfortable; there are bookcases sprinkled with the sparse library of a country lawyer, but lately plethoric, like the thin body which has departed in its coffin. Outside of this room, there is an office, where his secretaries sat – a room more narrow but as long – and opposite this adjacent office, a second door, directly behind Mr. Lincoln’s chair leads by a private passage to his family quarters. I am glad to sit here in his chair, where he has spent so often, – in the atmosphere of the household he purified, and the site of the green grass and the blue river he hallowed by gazing upon, in the very center of the nation he preserved for the people, and close the list of bloodied deeds, of desperate fights of swift expiations, of renowned obsequies of which I have written, by indicting at his table the goodness of his life and the eternity of his memory.”

“They are taking away Mr. Lincoln’s private effects, to deposit them wheresoever his family may abide, and the emptiness of the place, on this sunny Sunday, revives that feeling of desolation from which the land has scarce recovered. I rise from my seat and examine the maps; they are from the coast survey and engineer departments, and exhibit all the contested grounds of the war: there are pencil lines upon them where someone has traced the route of armies, and planned the strategic circumferences of campaigns. Was it the dead President who so followed the March of Empire, and dotted the sites of shock and overthrow? So, in the half-gloomy, half-grand apartment, roamed the tall and wrinkled figure whom the country had summoned from his plain home into mighty history, with the geography of the Republic drawn into a narrow compass so that he might lay his great brown hand upon it everywhere. And walking to and fro, to and fro, to measure the destinies of arms, he often stopped, with his thoughtful eyes upon the carpet, to ask if his life were real and he were the arbiter of so tremendous issues, or whether it was not all a fever-dream, snatched from his sofa in the routine office of the Prairie state.”

“I see some books on the table; perhaps they have lain there undisturbed since the reader’s dimming eyes grew nerveless. A parliamentary manual, a thesaurus, and two books of humor, “Orpheus C. Kerr,” and “Artemis Ward.” These last were read by Mr. Lincoln in the pauses of his hard day’s labor. Their tenure here bears out the popular verdict of his partiality for a good joke; and, through the window, from the seat of Mr. Lincoln, I see across the grassy grounds of the capitol, the broken shaft of the Washington Monument, the long bridge and the fort-tipped Heights of Arlington, reaching down to the shining riverside. These scenes he looked at often to catch some freshness of leaf and water, and often raised the sash to let the world rush in where only the nation abided, and hence on that awful night, he departed early, to forget this room and its close applications in the abandon of the theater. I wonder if it were the least of Booth’s crimes to slay this public servant and the stolen hour of recreation he enjoyed but seldom. We worked his life out here, and killed him when he asked a holiday.”

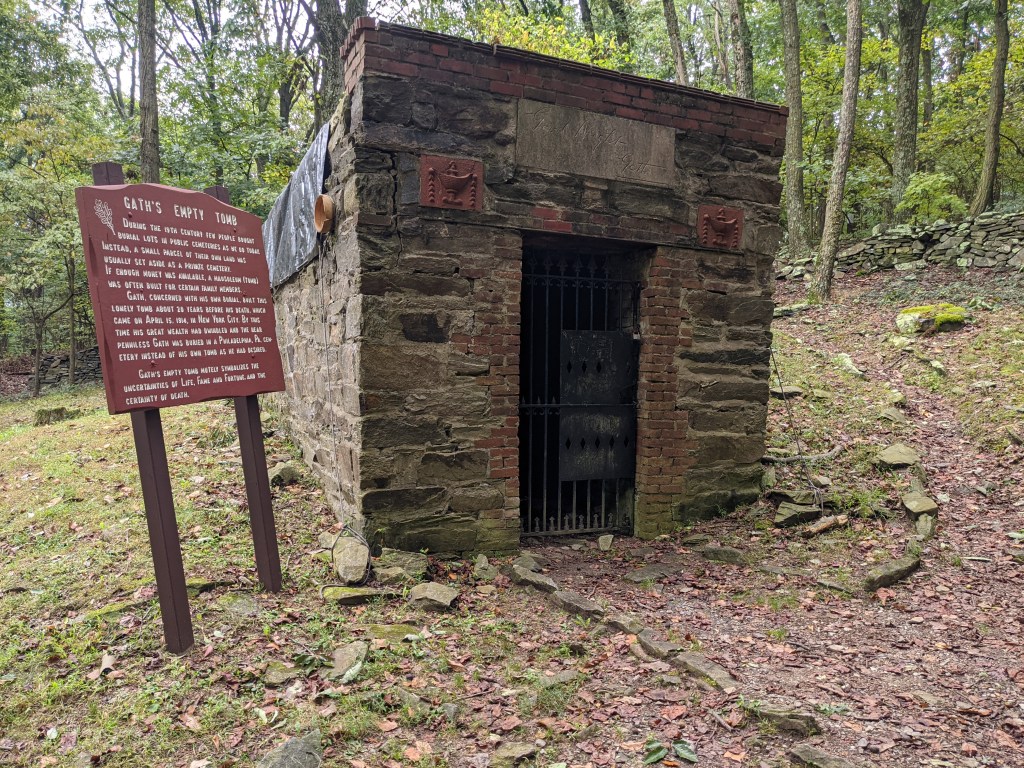

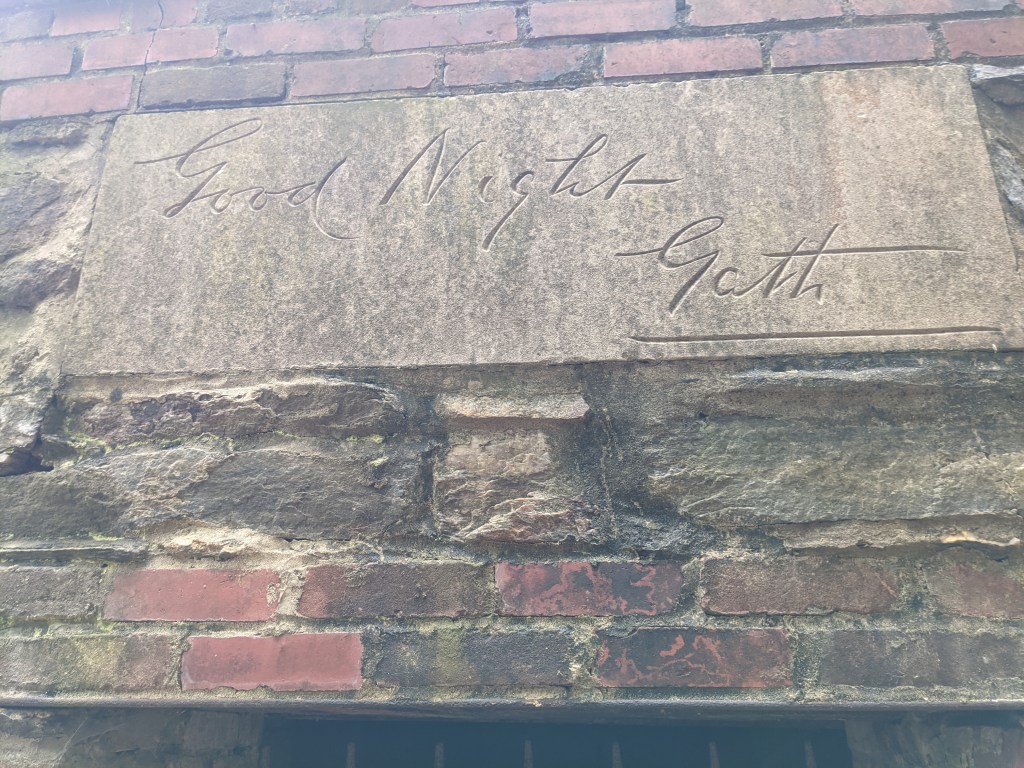

As one of the most successful journalists of his day, Townsend accumulated a tidy fortune. He used much of that fortune to build a 100-acre baronial estate near Crampton’s Gap, South Mountain, Maryland known as “Gapland”. The Civil War Battle of Crampton’s Gap was fought as part of the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, 1862, and resulted in 1,400 combined casualties. Tactically the battle resulted in a Union victory because they broke the Confederate line and drove through the gap. Strategically, the Confederates were successful in stalling the Union advance and were able to protect the rear. Gath literally bought the battlefield upon which he built his estate. The estate was composed of several buildings, including Gapland Hall, Gapland Lodge, the Den and Library Building, and a brick mausoleum (notable for its inscription of “Good Night Gath” above the entrance).

In 1896, Townsend built a monument to war correspondents to memorialize the contributions of his colleagues North and South. Dedicated in 1896, The War Correspondent Memorial Arch is 50 feet high and 40 feet wide and is the only monument in the world dedicated solely to war correspondents. Not only does the arch stand on Townsend’s original estate (operated by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources), it also rests smack dab in the middle of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail. Furthermore, the woods surrounding Gapland and the nearby town of Burkittsville were the setting for the 1999 horror film Blair Witch Project.

Last September, I traveled to the Catoctin Mountains to visit Townsend’s estate not far from the Antietam battlefield. Townsend’s Gapland estate is now known as Gathland State Park. Several buildings still stand, including Gapland Hall (which is the park headquarters) and the mausoleum, while other buildings are mere shadows of their former self. Townsend left Gapland in 1911 and died in New York City three years later on April 15, 1914. The 49th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s death. He was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.

His brick mausoleum, fronted by an ominous-looking iron gate causing it to look more like a jail cell than a tomb, stands empty, its roof slowly caving in. Although the object of my quest was The War Correspondent Memorial Arch, I could not help but spend most of my time seated beneath that empty tomb smoking a cigar. While the hale and hearty hikers pausing briefly at the foot of the Appalachian Trail might not have appreciated my vice, as I stared at the epitaph above the iron gate above Townsend’s unused tomb, George Alfred Townsend would understand. Good Night Gath.