Original publish date: November 25, 2008 Updated/Republished December 6,2018

As Christmas morning creeps ever-closer, parents all over the Hoosier state are making their lists and checking them twice. No doubt, at least a few of those lists will include a bicycle. I’m not sure if the bike retains the same lofty perch it did a half a century ago. I’m equally unsure if moms and dads still spend the hours after midnight busting knuckles, pinching fingers and squinting hopelessly at indecipherable directions written in more than one language.

The bicycle has become almost an afterthought in today’s world. But once, it truly was the eighth wonder of the world. The bicycle introduced a radical new invention known as the “pneumatic tire”. In addition to air-filled rubber tires, we can thank the bicycle for giving us ball bearings, devised to reduce friction in the bicycle’s axle and steering column, for wire spokes, and for differential gears that allow connected wheels to spin at different speeds.

And where would our airplanes, golf clubs, tent poles and lawn furniture be without the metal tubing used in bicycle frames to lighten the vehicle without compromising its strength? Bicycles also gave birth to our national highway system, as cyclists and cycling clubs outside major cities across the country tired of rutted mud paths and began lobbying for the construction of paved roads. What’s more, many of the bicycle repair shops were the breeding grounds for a number of pioneers in the transportation industry, including carmakers Henry Ford and Charles Duryea and aviation pioneers Orville and Wilbur Wright. All of these men started out as bicycle mechanics. And did you know that Indianapolis was on the cutting edge of the bicycle industry from the very beginning?

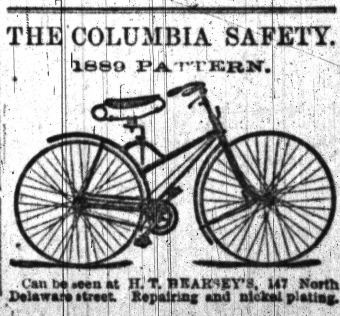

Although the first documented appearance of a bicycle in Indianapolis can be traced to a demonstration of the high-wheeled bike called the “Ordinary” in 1869, these old fashioned contraptions (known back then as “Velocipedes”) would be almost unrecognizable to the riders of today. With their huge front tires and seats that seemed to require a ladder to climb up to, these early bikes were awkward and unwieldy for use by all but the most hardy of daredevil souls (They didn’t call them “boneshakers” for nothing back then). It would take nearly 25 years after the close of the American Civil War before the bike began to resemble the form most familiar to riders of today. The development of the safety bike with it’s 2 equal-sized wheels in the 1880s made the new sport more acceptable as a hobby and pastime.

Although the first documented appearance of a bicycle in Indianapolis can be traced to a demonstration of the high-wheeled bike called the “Ordinary” in 1869, these old fashioned contraptions (known back then as “Velocipedes”) would be almost unrecognizable to the riders of today. With their huge front tires and seats that seemed to require a ladder to climb up to, these early bikes were awkward and unwieldy for use by all but the most hardy of daredevil souls (They didn’t call them “boneshakers” for nothing back then). It would take nearly 25 years after the close of the American Civil War before the bike began to resemble the form most familiar to riders of today. The development of the safety bike with it’s 2 equal-sized wheels in the 1880s made the new sport more acceptable as a hobby and pastime.

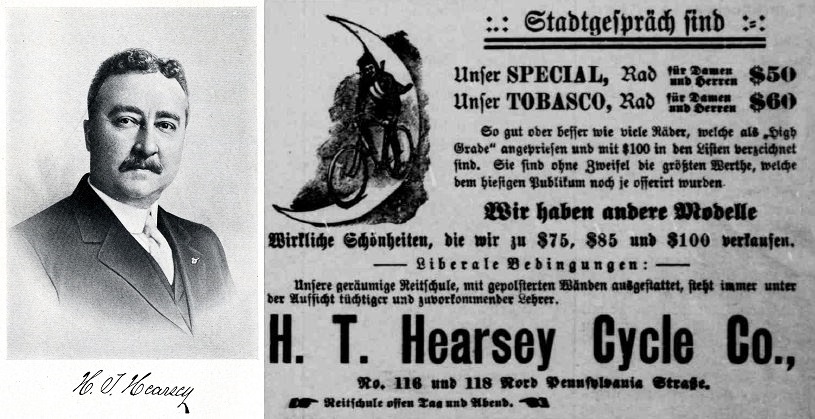

In 1887 bicycle mechanic and expert rider Henry T. Hearsey (1863-1939) opened the first bicycle showroom in Indianapolis. His store was located at the intersection of Delaware and New York Streets on the city’s near eastside. Hearsey introduced the first safety bike to Indianapolis, the English-made Rudge, which sold for the princely sum of $150 (roughly $4,000 in today’s money). Keep in mind that was about twice the price of a horse and buggy at the time. He would later open a larger shop at 116-118 North Pennsylvania Street. He is credited for introducing the 1st safety bicycle in the Capitol city in 1889. Hoosiers took to it immediately and within a few short years, the streets of Indy were so clogged with bicyclists that the City Council passed a bicycle licensing ordinance requiring a $ 1 license fee for every bicycle in the city.

In 1887 bicycle mechanic and expert rider Henry T. Hearsey (1863-1939) opened the first bicycle showroom in Indianapolis. His store was located at the intersection of Delaware and New York Streets on the city’s near eastside. Hearsey introduced the first safety bike to Indianapolis, the English-made Rudge, which sold for the princely sum of $150 (roughly $4,000 in today’s money). Keep in mind that was about twice the price of a horse and buggy at the time. He would later open a larger shop at 116-118 North Pennsylvania Street. He is credited for introducing the 1st safety bicycle in the Capitol city in 1889. Hoosiers took to it immediately and within a few short years, the streets of Indy were so clogged with bicyclists that the City Council passed a bicycle licensing ordinance requiring a $ 1 license fee for every bicycle in the city.

Henry Hearsey had fallen in love with Indianapolis during an exhibition tour for the Cunningham-Heath bicycle company of Boston, Massachusetts in 1885. He not only sold the first new style bicycles in the Indy area, he also formed the first riding clubs in the city. These clubs, with colorful names like the “U.S. Military Wheelmen”, the “Zig-Zag Cycling Club” and the “Dragon Cycle Club”, would regularly host festive long distance bicycle trips known as “Century Rides” to towns like Greenfield and Bloomington. This period has been called the “Golden Age of Bicycling” by historians. Hearsey also had two famous names working for him at his bike shop: Carl Fisher and Major Taylor.

Legendary Indianapolis African American bicycle champion Marshall “Major” Taylor was hired by Henry Hearsey to perform bicycle stunts outside of his shop in 1892. 14-year-old Taylor’s job was as “head trainer” teaching local residents how to ride the new machines.Taylor performed his stunts while dressed in a military uniform and earned  the nickname “Major”, which stuck with him the rest of his life. He has been widely acknowledged as the first American International superstar of bicycle racing. He was the first African American to achieve the level of world champion and the second black athlete to win a world championship in any sport. Carl Fisher was one of the founders of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, developer of the city of Miami and the creator of the famous “Lincoln Highway” and the “Dixie Highway.”

the nickname “Major”, which stuck with him the rest of his life. He has been widely acknowledged as the first American International superstar of bicycle racing. He was the first African American to achieve the level of world champion and the second black athlete to win a world championship in any sport. Carl Fisher was one of the founders of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, developer of the city of Miami and the creator of the famous “Lincoln Highway” and the “Dixie Highway.”

His innovations included the installation of a revolutionary foot air bellows system that would be known for decades as the “town pump” for public use outside of his store. His shop became a popular hangout for the city’s bicyclists who liked to drop in and rub elbows with all of the greatest bike racers of the age. Indianapolis was a midwest mecca for pro-bicycling in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Hearsey would often use the massive Tomlinson Hall in Indy to unveil the newest model of bicycle in the 1890s. Tomlinson Hall was the largest public venue in the city and Hearsey would routinely fill the place to the rafters with excited Hoosier bicyclists, which would be like renting Lucas Oil Stadium to unveil a new bike today. Cycling in the Circle City was so popular that on April 28, 1895 the Indianapolis Journal ran an eight-page supplement called the “Bicycle Edition” entirely devoted to the cycling craze consuming the Hoosier State and the rest of the country.

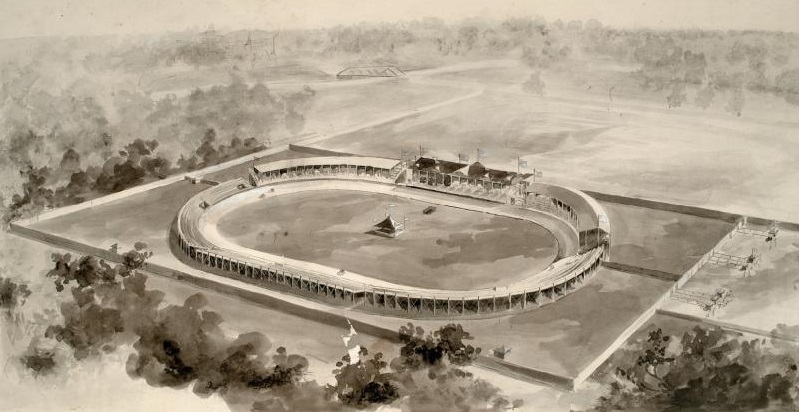

Cycling was so popular in Indianapolis that the city constructed a racing track known as the “Newby Oval” located near 30th Street and Central Avenue in 1898. The track was designed by Shortridge graduate Herbert Foltz who also designed the Broadway Methodist Church, Irvington United Methodist Church and the Meridian Heights Presbyterian Church. Foltz would also design the new Shortridge High School at 34th and Meridian. The state of the art cycling facility could, and often did, seat 20,000 and hosted several national championships sponsored by the chief sanctioning body, “The League of American Wheelmen.” The American Wheelmen often got involved in local and national politics. Hoosier wheelmen raced into the William McKinley presidential campaign in 1896 and helped him win the election. With this new found political clout, riding clubs began to put pressure on politicians to improve urban streets and rural roads, exclaiming “We are a factor in politics, and demand that the great cause of Good Roads be given consideration.”

Cycling was so popular in Indianapolis that the city constructed a racing track known as the “Newby Oval” located near 30th Street and Central Avenue in 1898. The track was designed by Shortridge graduate Herbert Foltz who also designed the Broadway Methodist Church, Irvington United Methodist Church and the Meridian Heights Presbyterian Church. Foltz would also design the new Shortridge High School at 34th and Meridian. The state of the art cycling facility could, and often did, seat 20,000 and hosted several national championships sponsored by the chief sanctioning body, “The League of American Wheelmen.” The American Wheelmen often got involved in local and national politics. Hoosier wheelmen raced into the William McKinley presidential campaign in 1896 and helped him win the election. With this new found political clout, riding clubs began to put pressure on politicians to improve urban streets and rural roads, exclaiming “We are a factor in politics, and demand that the great cause of Good Roads be given consideration.”

During this turn-of-the-century era, Indianapolis became one of the leading manufacturers of bicycles in the United States with companies like Waverly, Munger, Swift, Outing, Eclipse and the Ben-Hur offering some of the finest riding machines of the day. According to the Indiana Historical Bureau, from 1895-96, Indianapolis had nine bicycle factories employing nearly 1,500 men, women and boys. Not to mention a couple dozen repair shops, parts suppliers and specialty stores stocking bicycle attire like collapsible drinking cups, canteens, hats, goggles, shoes and clothing.

In the years before World War I, two entire city blocks around Pennsylvania Avenue became known as “bicycle alley”. Here bicycle enthusiasts congregated among the many manufacturers, outfitters and repair shops to talk shop, swap stories and plan routes. Some of the more popular spots to ride in the Circle City included 16th Street and Senate Avenue, Broad Ripple and the tow path along the Central Canal.

The gem of Indianapolis’ cycling community was the Newby Oval on Central Avenue and 13th Street. The $23,000, quarter-mile track featured a surface made of white pine boards, rough side up to keep wheels from slipping. Wire brushing removed splinters before the floorboards were dipped into a tank of wood preservative and nailed into place. The track featured a “whale-back” design of banked curves to increase safety and accommodate speed. The Newby Oval featured grandstand seating, two amphitheaters, and bleachers designed to hold more than 8,000 spectators.

The Newby Oval’s first race, sponsored by the League of American Wheelmen hosted its first bike race on July 4, 1898. The contest included ragtime, two-step, and patriotic tunes to serenade the riders and spectators alike. Every time a rider neared the finish line, spectators fired their pistols in the air in anticipation. For a time, the Newby Oval was considered to host the city’s first automobile race. The euphoria didn’t last long though. Because cars would need to run in separate heats at the Newby Oval, the event was moved to the State Fairgrounds, where multiple vehicles could compete at one time. The track’s building materials were put up for sale and by early 1903, the Newby Oval was dismantled. By the turn-of-the-century, interest in cars was outpacing bicycles. By 1908, the bicycle craze was over.

With the advent of the automobile and motorcycles in the early 1910s, interest in bicycling as a form of transportation waned. Henry T. Hearsey changed with the times and became Indianapolis’ first automobile dealer. Hearsey lived at 339 East Tippencanoe Street, just a stone’s throw away from the James Whitcomb Riley house in Lockerbee Square. Indianapolis, just as it had in the generation before with bicycles, soon become a pioneer in the manufacture of automobiles, second only to Detroit in fact. Most of the parties involved in the Indianapolis Motor Speedway were former colleagues of Henry Hearsey and members of his bicycle clubs.

While images of the old fashioned high-wheeled “ordinary” bicycles and the winged tire logo of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway are instantly recognizable to sports fans all over the world, no-one remembers Henry T. Hearsey today. Hearsey not only introduced Indianapolis to the first commercially viable bicycle, opened the first Circle City bicycle shop, was the first to recognize the genius of Major Taylor and Carl Fisher and opened the first car dealership in the city. He was born during the Civil War, flourished during the Gilded Age / Industrial Age / Progressive Era / Roaring Twenties and survived the Great Depression. Henry T. Hearsey, the trailblazing businessman whose name is unknown to most Hoosiers, died in the summer of 1939. He lies buried in Crown Hill Cemetery among the many notable names from the pages of Indianapolis’ history, most of whom knew him personally and called him by his nickname. Happy holidays “Harry” Hearsey, the Circle City tips its collective cap to you.

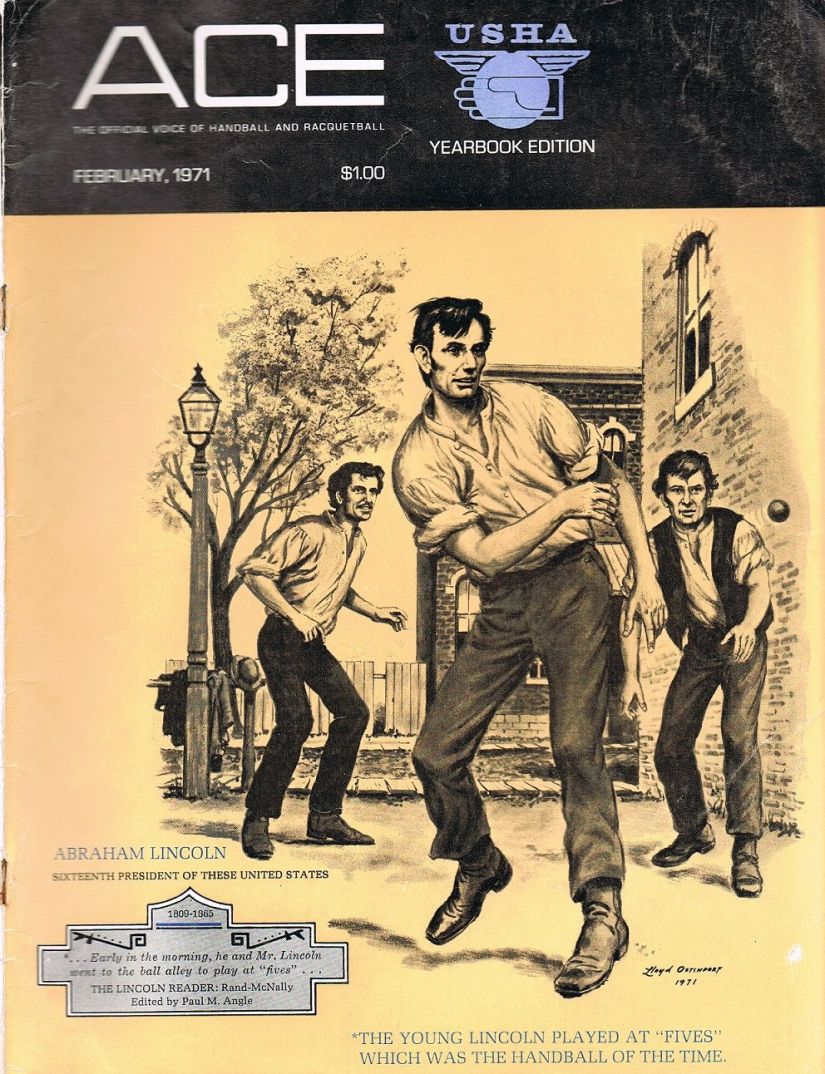

Likewise, you may have heard that he was a handball player, as have I, but details have always been hard to find. The game of handball was much better suited to Lincoln. At 6 feet 4 inches tall, his long legs and gangly arms served the rail splitter well. Muscles honed while wielding an axe as a youth were kept tight and toned as an adult. Lincoln milked his own cows and chopped his own wood even though he was a successful, affluent lawyer with little time to spare.

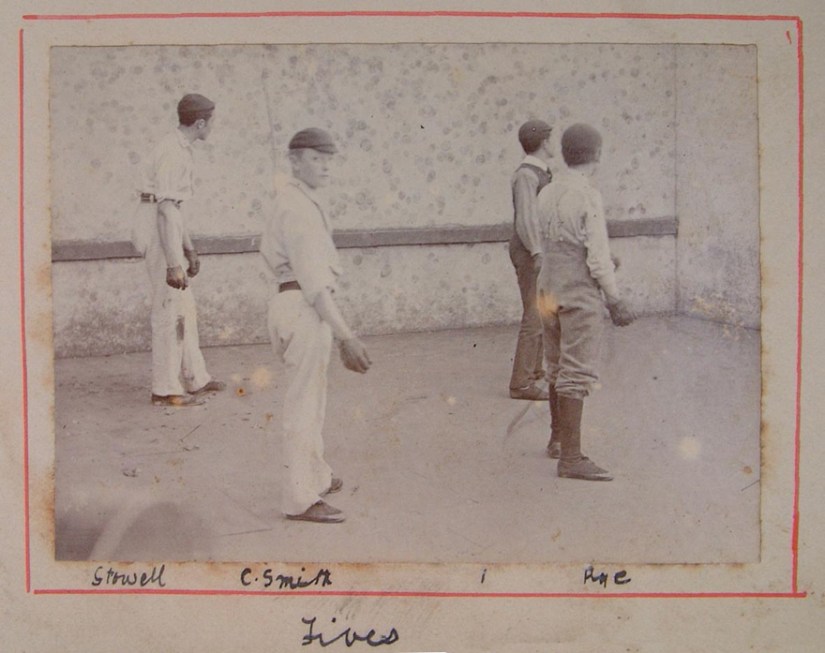

Likewise, you may have heard that he was a handball player, as have I, but details have always been hard to find. The game of handball was much better suited to Lincoln. At 6 feet 4 inches tall, his long legs and gangly arms served the rail splitter well. Muscles honed while wielding an axe as a youth were kept tight and toned as an adult. Lincoln milked his own cows and chopped his own wood even though he was a successful, affluent lawyer with little time to spare. The term handball really didn’t exist in Lincoln’s day. It was called a “game of fives” by Abe and his contemporaries. When Mr. Lincoln went to town, he frequently joined with the boys in playing handball. In the Springfield version, players choose sides to square off against one another. The game is begun by one of the boys bouncing the ball against the wall of the Logan building. As it bounced back, and opponent strikes it in the same manner, so that the ball is kept going back and forth against the wall until someone misses the rebound. ‘Old Abe’ was often the winner, for his long arms and long legs served a good purpose in reaching and returning the ball from any angle his adversary could send it to the wall. The game required two, four or six players, spread equally on each side. The three players who lost paid 10 ¢ each, making 30 ¢ a game. So as you can imagine the games got pretty serious.

The term handball really didn’t exist in Lincoln’s day. It was called a “game of fives” by Abe and his contemporaries. When Mr. Lincoln went to town, he frequently joined with the boys in playing handball. In the Springfield version, players choose sides to square off against one another. The game is begun by one of the boys bouncing the ball against the wall of the Logan building. As it bounced back, and opponent strikes it in the same manner, so that the ball is kept going back and forth against the wall until someone misses the rebound. ‘Old Abe’ was often the winner, for his long arms and long legs served a good purpose in reaching and returning the ball from any angle his adversary could send it to the wall. The game required two, four or six players, spread equally on each side. The three players who lost paid 10 ¢ each, making 30 ¢ a game. So as you can imagine the games got pretty serious. Court clerk Thomas W.S. Kidd spoke of Mr. Lincoln’s love of the game: “In 1859, Zimri A. Enos, Esq., Hon. Chas. A. Keyes, E. L. Baker, Esq., then editor of the Journal, William A. Turney, Esq., Clerk of the Supreme Court, and a number of others, in connection with Mr. Lincoln, had the lot, then an open one, lying between what was known as the United States Court Building, on the northeast corner of the public square, and the building owned by our old friend, Mr. John Carmody, on the alley north of it, on Sixth street, enclosed with a high board fence, leaving a dead wall at either end. In this ‘alley’ could be found Mr. Lincoln, with the gentlemen named and others, as vigorously engaged in the sport as though life depended upon it. He would play until nearly exhausted and then take a seat on the rough board benches arranged along the sides for the accommodation of friends and the tired players.”

Court clerk Thomas W.S. Kidd spoke of Mr. Lincoln’s love of the game: “In 1859, Zimri A. Enos, Esq., Hon. Chas. A. Keyes, E. L. Baker, Esq., then editor of the Journal, William A. Turney, Esq., Clerk of the Supreme Court, and a number of others, in connection with Mr. Lincoln, had the lot, then an open one, lying between what was known as the United States Court Building, on the northeast corner of the public square, and the building owned by our old friend, Mr. John Carmody, on the alley north of it, on Sixth street, enclosed with a high board fence, leaving a dead wall at either end. In this ‘alley’ could be found Mr. Lincoln, with the gentlemen named and others, as vigorously engaged in the sport as though life depended upon it. He would play until nearly exhausted and then take a seat on the rough board benches arranged along the sides for the accommodation of friends and the tired players.” Lincoln’s friend, Dr. Preston H Bailhache, recalled a handball game played on a court built by Patrick Stanley in an ‘alley’ in the rear of his grocery in the Second Ward, which is still standing. “I have sat and laughed many happy hours away watching a game of ball between Lincoln on one side and Hon. Chas. A. Keyes on the other. Mr. Keyes is quite a short man, but muscular, wiry and active as a cat, while his now more distinguished antagonist, as all now know, was tall and a little awkward, but which with much practice and skill in the movement of the ball, together with his good judgment, gave him the greatest advantage. In a very hotly contested game, when both sides were ‘up a stump’ – a term used by the players to indicate an even game – and while the contestants were vigorously watching every movement, Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Turney collided with such force that it came very near preventing his nomination to the Presidency, and giving to Springfield a sensation by his death and burial. Both were badly hurt, but not so badly as to discourage either from being found in the ‘alley’ the next day.”

Lincoln’s friend, Dr. Preston H Bailhache, recalled a handball game played on a court built by Patrick Stanley in an ‘alley’ in the rear of his grocery in the Second Ward, which is still standing. “I have sat and laughed many happy hours away watching a game of ball between Lincoln on one side and Hon. Chas. A. Keyes on the other. Mr. Keyes is quite a short man, but muscular, wiry and active as a cat, while his now more distinguished antagonist, as all now know, was tall and a little awkward, but which with much practice and skill in the movement of the ball, together with his good judgment, gave him the greatest advantage. In a very hotly contested game, when both sides were ‘up a stump’ – a term used by the players to indicate an even game – and while the contestants were vigorously watching every movement, Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Turney collided with such force that it came very near preventing his nomination to the Presidency, and giving to Springfield a sensation by his death and burial. Both were badly hurt, but not so badly as to discourage either from being found in the ‘alley’ the next day.” Another eyewitness was the unofficial gatekeeper of the Handball Court, William Donnelly, a nephew of John Carmody. Years later, Donnelly offered this account to a reporter, “I worked in the Carmody store and usually had charge of the ball court. I smoothed the wall and leveled the ground. I made the balls. Old stockings were rolled out and wound into balls and covered with buckskin. Mr. Lincoln was not a good player. He learned the game when he was too old. But he liked to play and did tolerably well. I remember when he was nominated as though it were yesterday. It was the last day of the convention and he was plainly nervous and restless.”

Another eyewitness was the unofficial gatekeeper of the Handball Court, William Donnelly, a nephew of John Carmody. Years later, Donnelly offered this account to a reporter, “I worked in the Carmody store and usually had charge of the ball court. I smoothed the wall and leveled the ground. I made the balls. Old stockings were rolled out and wound into balls and covered with buckskin. Mr. Lincoln was not a good player. He learned the game when he was too old. But he liked to play and did tolerably well. I remember when he was nominated as though it were yesterday. It was the last day of the convention and he was plainly nervous and restless.” John Carmody recalled another handball game: “An incident took place, during one of those games, which I have retained clearly in my memory. I had a nephew named Patrick Johnson who was very expert in the game. He struck the ball in such a manner that it hit Mr. Lincoln in the ear. I ran to sympathize with him and asked if he was hurt. He said he was not, and as he said it he reached both of his hands toward the sky. Straining my neck to look up into his face, for he was several inches taller than I was, I said to him, ‘Lincoln, if you are going to heaven, take us both.’”

John Carmody recalled another handball game: “An incident took place, during one of those games, which I have retained clearly in my memory. I had a nephew named Patrick Johnson who was very expert in the game. He struck the ball in such a manner that it hit Mr. Lincoln in the ear. I ran to sympathize with him and asked if he was hurt. He said he was not, and as he said it he reached both of his hands toward the sky. Straining my neck to look up into his face, for he was several inches taller than I was, I said to him, ‘Lincoln, if you are going to heaven, take us both.’” In October of 2004, the Smithsonian Institution displayed Abraham Lincoln’s handball as part of their exhibit “Sports: Breaking Records, Breaking Barriers.” It’s small (about the size of a tennis ball), dirty and well worn and really, really old. The ball has “No. 2” stamped on the side but it is unclear if the stamp was on the ball when Lincoln handled it or if it was stamped on the side for reference years later. It came from the Lincoln Home in Springfield, where Lincoln lived with his family from 1844 until 1861.

In October of 2004, the Smithsonian Institution displayed Abraham Lincoln’s handball as part of their exhibit “Sports: Breaking Records, Breaking Barriers.” It’s small (about the size of a tennis ball), dirty and well worn and really, really old. The ball has “No. 2” stamped on the side but it is unclear if the stamp was on the ball when Lincoln handled it or if it was stamped on the side for reference years later. It came from the Lincoln Home in Springfield, where Lincoln lived with his family from 1844 until 1861. Although Assassin John Wilkes Booth was not in the production, he would appear at the McVicker’s 4 times in different productions between 1862 & 1863 while Mr. Lincoln was in the White House. Ironically, the McVickers Theatre was the very first place where actor Harry Hawk began theater work as a call boy, or stagehand. Hawk was the actor on stage alone at the moment of Lincoln’s assassination and likely uttered the last words Mr. Lincoln ever heard. Who knew a well worn piece of leather sports equipment could have so many connections?

Although Assassin John Wilkes Booth was not in the production, he would appear at the McVicker’s 4 times in different productions between 1862 & 1863 while Mr. Lincoln was in the White House. Ironically, the McVickers Theatre was the very first place where actor Harry Hawk began theater work as a call boy, or stagehand. Hawk was the actor on stage alone at the moment of Lincoln’s assassination and likely uttered the last words Mr. Lincoln ever heard. Who knew a well worn piece of leather sports equipment could have so many connections?