Original publish date: February 20, 2020

Recently, I wrote a two-part series on Carnation Day, the little known holiday created to honor our third assassinated President, William McKinley. While researching that story, I came across a man whose name should rightly echo through the halls of American heroism. Instead, his name is forgotten, his place in history supplanted and his whereabouts remain unknown.

William McKinley’s presence at the the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York was no accident. McKinley loved world’s fairs. The President referred to them as, “the timekeepers of progress. They record the world’s advancement.” He attended the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and the Cotton States Exposition in Atlanta two years later. He did not want to miss the Buffalo Expo, planned for the summer of 1901, his first World’s Fair as President.

On September 6, 1901, President McKinley spent his final hours on earth acting like a regular tourist. He awoke early at 7:15 A.M., dressed for the day in his heavy black frock coat and black silk tophat, and stealthily dodged his Secret Service guards for a solitary stroll down Delaware Avenue. Later that morning, William and Ida McKinley boarded a train for Niagara Falls. They visited the falls, walked along the gorge, and toured the Niagara Falls Power Project, which the President referred to as “the marvel of the Electrical Age.” After returning to Buffalo, Mrs. McKinley went to the Milburn house to rest, the president to the exposition and his date with destiny.

The president was scheduled to meet the thousands of people who, in spite of the oppressive heat, were waiting at the Temple of Music on the north side of the fairgrounds. In that line, no one stood out more than James “Big Ben” Parker, a six-foot six inch, 250 pound “Negro” waiter from Atlanta who has been laid off by the exposition’s Plaza Restaurant only days before. One could conclude that “Big Ben” was the angriest man in the room and the one the Secret Service should be watching. However, that sobriquet would belong to the man standing immediately in front of the gentle giant. A stoop-shouldered, nervous little man whose hand was wrapped in a handkerchief.

The president was scheduled to meet the thousands of people who, in spite of the oppressive heat, were waiting at the Temple of Music on the north side of the fairgrounds. In that line, no one stood out more than James “Big Ben” Parker, a six-foot six inch, 250 pound “Negro” waiter from Atlanta who has been laid off by the exposition’s Plaza Restaurant only days before. One could conclude that “Big Ben” was the angriest man in the room and the one the Secret Service should be watching. However, that sobriquet would belong to the man standing immediately in front of the gentle giant. A stoop-shouldered, nervous little man whose hand was wrapped in a handkerchief.

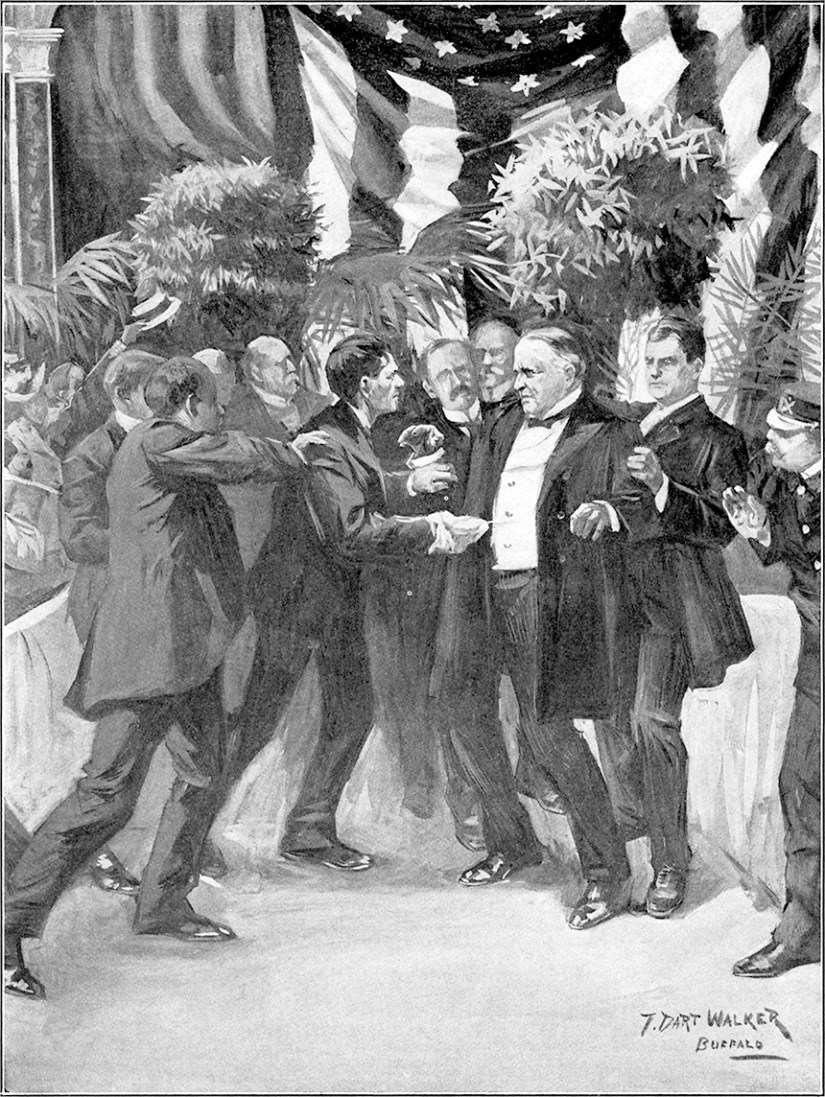

Parker had been waiting outside the temple all morning. He wanted to be at the head of the line to meet the president. At 4:00 P.M. the doors of the Temple of Music opened and hundreds of people formed an orderly, single-file line to the front of the auditorium. Once members of the public shook hands with McKinley, they would continue on to exit the building. An American flag was draped behind the President and several potted plants were arrayed around him to create an attractive scene. There President McKinley, flanked by his personal secretary George Cortelyou and Fair organizer John Milburn, stood waiting.

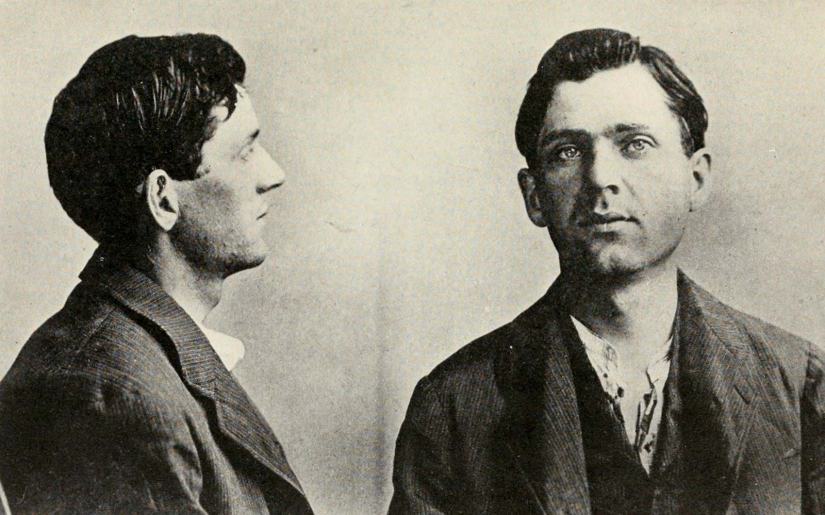

The pipe organ began to play “The Star-Spangled Banner”. The room was over ninety degrees. Everybody was carrying handkerchiefs to wipe their brows or to wave at the president. Anarchist Leon Czolgosz (pronounced “zoll-goss”), although sweating profusely, was doing neither. His handkerchief was wrapped around his right hand like a bandage held tightly to his chest. No one suspected there was a revolver hidden underneath. The usual rule enforced by the Secret Service was that all those who approached the President must do so with their hands open and empty. Likely due to the scorching heat inside the breezeless building, that rule was not being enforced as everyone seemed to be carrying handkerchiefs.

McKinley could shake hands with 50 people per minute by first gripping their hands then guiding them quickly past while preventing his fingers from being squeezed at the same time. McKinley, seeing Czolgosz’s bandaged right hand, instinctively reached for his left hand instead. At 4:07 pm, as the two men’s hands touched, the assassin raised the makeshift sling and fired his hidden .32 Iver Johnson revolver twice.

The first bullet sheared a button off of McKinley’s vest, the second tore into the President’s abdomen. The handkerchief burst into flames and fell to the floor. McKinley lurched forward as Czolgosz took aim for a third shot. Within seconds after the second pistol shot, Big Ben Parker was grappling with the adrenaline charged assassin. Secret service special agent Samuel Ireland described the scene: “Parker struck the assassin in the neck with one hand and with the other reached for the revolver which had been discharged through the handkerchief and the shots had set fire to the linen. While on the floor Czolgosz again tried to discharge the revolver but before he got to the president the Negro knocked it from his hand.” A split second after Parker struck Czolgosz, so did Buffalo detective John Geary and one of the artillerymen, Francis O’Brien. Czolgosz disappeared beneath a pile of men, some of whom were punching or hitting him with rifle butts. The assassin cried out, “I done my duty.”

The first bullet sheared a button off of McKinley’s vest, the second tore into the President’s abdomen. The handkerchief burst into flames and fell to the floor. McKinley lurched forward as Czolgosz took aim for a third shot. Within seconds after the second pistol shot, Big Ben Parker was grappling with the adrenaline charged assassin. Secret service special agent Samuel Ireland described the scene: “Parker struck the assassin in the neck with one hand and with the other reached for the revolver which had been discharged through the handkerchief and the shots had set fire to the linen. While on the floor Czolgosz again tried to discharge the revolver but before he got to the president the Negro knocked it from his hand.” A split second after Parker struck Czolgosz, so did Buffalo detective John Geary and one of the artillerymen, Francis O’Brien. Czolgosz disappeared beneath a pile of men, some of whom were punching or hitting him with rifle butts. The assassin cried out, “I done my duty.”

A Los Angeles Times story said that “with one quick shift of his clenched fist, he [Parker] knocked the pistol from the assassin’s hand. With another, he spun the man around like a top and with a third, he broke Czolgosz’s nose. A fourth split the assassin’s lip and knocked out several teeth.” In Parker’s own account, given to a newspaper reporter a few days later, he said, “I heard the shots. I did what every citizen of this country should have done. I am told that I broke his nose—I wish it had been his neck. I am sorry I did not see him four seconds before. I don’t say that I would have thrown myself before the bullets. But I do say that the life of the head of this country is worth more than that of an ordinary citizen and I should have caught the bullets in my body rather than the President should get them.” In a separate interview for the New York Journal, Parker remarked “just think, Father Abe freed me, and now I saved his successor from death, provided that bullet he got into the president don’t kill him.”

A Los Angeles Times story said that “with one quick shift of his clenched fist, he [Parker] knocked the pistol from the assassin’s hand. With another, he spun the man around like a top and with a third, he broke Czolgosz’s nose. A fourth split the assassin’s lip and knocked out several teeth.” In Parker’s own account, given to a newspaper reporter a few days later, he said, “I heard the shots. I did what every citizen of this country should have done. I am told that I broke his nose—I wish it had been his neck. I am sorry I did not see him four seconds before. I don’t say that I would have thrown myself before the bullets. But I do say that the life of the head of this country is worth more than that of an ordinary citizen and I should have caught the bullets in my body rather than the President should get them.” In a separate interview for the New York Journal, Parker remarked “just think, Father Abe freed me, and now I saved his successor from death, provided that bullet he got into the president don’t kill him.”

Parker clearly prevented Czolgosz from firing a third time, thereby saving McKinley’s life. However, poor medical technique would ultimately cause McKinley’s death. The wound was closed without disinfecting (sterilization being a fairly new concept at the time) so McKinley died of gangrene on September 14, 1901. Prior to McKinley’s death, when his outlook for recovery appeared promising, the Savannah Tribune, an African-American newspaper, trumpeted of Parker “the life of our chief magistrate was saved by a Negro. No other class of citizens is more loyal to this country than the Negro.” A Sept. 12 , 1901 Buffalo Times article described “Big Ben” as a “plain, modest, gentlemanly person”.

Later, Parker told a slightly different version of his story to the Buffalo Times. “I went to the Temple of Music to hear what speeches might be made. I got in line and saw the President. I turned to go away as soon as I learned that there was to be only a handshaking. The crowd was so thick that I could not leave. I was startled by the shots. My fist shot out and I hit the man on the nose and fell upon him, grasping him about the throat. I believe that if he had not been suffering pain he would have shot again. I know that his revolver was close to my head. I did not think about that then though. Then came Mr. Foster, Mr. Ireland and Mr. Gallagher. There was that marine, too. I struck the man, threw up his arm and then went for his throat. It all happened so quickly I can hardly say what happened, except that the secret service man came right up.Czolgosz is very strong. I am glad that I am a strong man also or perhaps the result might not have been what it was.”

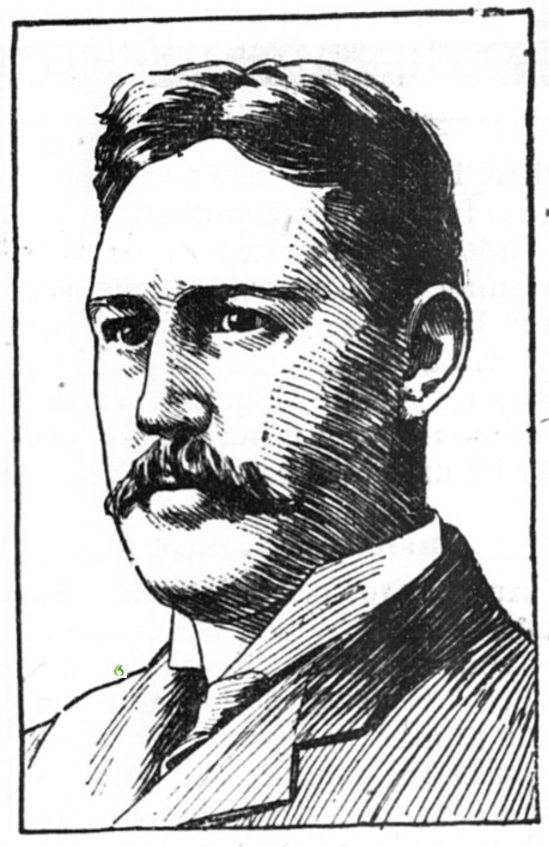

James Benjamin Parker, an American of African and Spanish descent, was born on July 31, 1857 in Atlanta, Georgia to enslaved parents. Educated in Atlanta schools, he also traveled as far north as Philadelphia, but returned south to live in Savannah. At one time he had been a salesman for the Southern Recorder newspaper. While in Savannah Parker was a well respected constable for a Negro magistrate. Big Ben had the reputation of never returning an unserved warrant. The citizens of the East Side of Savannah also knew that he was man of few words and a command to submit to arrest was always quietly obeyed. For a time, Big Ben lived in Chicago and worked as waiter in the Pullman Car organization. He returned to Atlanta in 1895. When he relocated to New York City, Ben had only one living relative, his mother in Savannah. Prior to coming to Buffalo, he was in Saratoga, New York and came to Buffalo only days before the assassination to work at the Exposition for the Bailey Catering Co.

According to a September 10, 1901 newspaper article, after the incident Parker appeared near the west gate of the Pan American Exposition Mall. As details of his heroism began to circulate through the crowd, a group of people surrounded him and asked the avenger to sell pieces of his waistcoat and other clothing. He recounted the story of the assassination and sold one button off his coat for $1.00 (equivalent to $30 today). After the shooting, Parker was approached with several commercial offers, including one from a company who wanted to sell his photograph. He was asked to work on the Midway at the Exposition recounting his story and signing autographs. He refused, telling the Sept. 13, 1901, Buffalo Commercial newspaper, “I happened to be in a position where I could aid in the capture of the man. I do not think that the American people would like me to make capital out of the unfortunate circumstances. I do not want to be exhibited in all kinds of shows. I am glad that I was able to be of service to the country.”

The Atlanta Constitution ran a story in the September 10 edition relating how the Negroes of Savannah were planning to set up a substantial testimonial for Parker. On September 13 another article ran titled “Negros Applaud Parker. Mass Meeting in Charleston Hears Booker Washington.” Booker T. Washington delivered an address to a mass meeting of 5,000 African Americans including a resolution denouncing the reckless deed of the “red handed anarchist” and rejoiced that a southern Negro “had saved the President McKinley from death.”

Historians agree that Czolgosz’s trial was a sham. Sadly, what should have been Big Ben Parker’s time to shine instead became his disappearing act. Prior to the trial, which began September 23, 1901, Parker was expected to be a major character in the assassination saga. Instead,the trial minimized Parker’s participation in the events of three weeks prior. Parker was never asked to testify and those few participants who did never identified Big Ben as the person who first subdued the assassin. Czolgosz’s sanity was never questioned and the case was closed twenty-four hours after it opened. Newspaper reports after the trial failed to mention Big Ben’s role and witnesses, including lawyers and Secret Service agents, began to enlarge their own roles in the tragedy by going as far as saying they “saw no Negro involved” whatsoever.

Historians agree that Czolgosz’s trial was a sham. Sadly, what should have been Big Ben Parker’s time to shine instead became his disappearing act. Prior to the trial, which began September 23, 1901, Parker was expected to be a major character in the assassination saga. Instead,the trial minimized Parker’s participation in the events of three weeks prior. Parker was never asked to testify and those few participants who did never identified Big Ben as the person who first subdued the assassin. Czolgosz’s sanity was never questioned and the case was closed twenty-four hours after it opened. Newspaper reports after the trial failed to mention Big Ben’s role and witnesses, including lawyers and Secret Service agents, began to enlarge their own roles in the tragedy by going as far as saying they “saw no Negro involved” whatsoever.

The African American community was outraged. Apparently, the Secret Service and the military were embarrassed that a private citizen, a black man at that, essentially brought the assassin down instead of them. When Parker was asked for comment, he said, ” I don’t say it was done with any intent to defraud, but it looks mighty funny, that’s all.” Parker remained humble, telling another reporter, “I am a Negro, and am glad that the Ethiopian race has what ever credit comes with what I did. If I did anything, the colored people should get the credit.”

The African American community of Buffalo held a ceremony to honor Parker at the Vine Street African Methodist Church on September 27, 1901. The church was packed to standing room only and the Buffalo News reported that the audience was incensed that no credit or recognition was given to Parker. The speaker, a church fellow named Shaw, delivered a short testimonial concluding by saying, “The evident attempt to discredit Parker is a sign of conspiracy and should we fail to emphatically resent it, I claim we are a disgrace to our race. ” When Big Ben entered the hall, he refused all demands to make a speech and sat down amidst cheers.

Methodist preacher Lena Doolin Mason wrote a poem praising Parker for his actions, “A Negro He Was In It”, casting Parker as the latest in a long line of African Americans who risked their lives in service to their country and admonishing white Americans to recognize that bravery with the cessation of lynchings. To quell the simmering pot of racial tension, the U.S. Government publicly promised a lifetime government job for Big Ben Parker, but no such job ever materialized. James A. Ross, the “colored mason”, Buffalo politician and publisher of the “Gazetteer and Guide” (a magazine for Negro railroad porters and hotel workers), supported Parker’s heroism by hiring him to be a traveling agent (magazine salesman) for his publication. With this, Parker left Buffalo after the trial and dropped from public view.

The April 4, 1908 edition of the Richmond (Virginia) Planet newspaper reported, “Before a class of students at the Jefferson Medical College the body of James B. Parker, colored, was placed upon the dissecting table Thursday. Parker was the man who beat Louis Czolgosz to the ground and disarmed him after the latter had fired two shots into the body of President McKinley at Buffalo on September 6,1901. At the time of the President’s assassination Parker was a Pullman car porter. Like many other heroes of the present day, Parker died penniless, his death came almost two weeks ago at the Philadelphia Hospital, where he was a patient in the insane department. He was moved to the West Philadelphia institution several months ago, after having been picked up by the police. As far as known he had no friends in this city at the time of his death and the body was turned over to the State Anatomical Board. In this way it came into possession of the college authorities. Parker was petted by thousands of persons in Buffalo. Everybody praised him, and it was thought for a time, that his act had saved the President’s life. Senator Mark Hanna, of Ohio, presented Parker with a check for $1,000 in appreciation of his bravery. Parker was well proportioned and was six feet four inches in height. In his earlier days he was employed as a letter carrier in Atlanta, Ga. More than a year ago he came to this city, and the last heard of him before his death was his arrest in West Philadelphia. In speaking of his tussle with Czolgosz, Parker said the assassin fought like a tiger and was one of the most powerful men he had ever tussled with. His brain will be examined by a noted alienist of the city within the next few weeks and it is expected that it will prove one of the most interesting studies ever made in Philadelphia.” His final resting place remains unknown.

Just as Big Ben is the forgotten figure in the McKinley assassination saga, Leon Czolgosz is the least known of all presidential assassins. Prior to his execution Czolgosz met with two priests and said, “No. Damn them. Don’t send them here again. I don’t want them. And don’t you have any praying over me when I’m dead. I don’t want it. I don’t want any of their damned religion.” Czolgosz was electrocuted on October 29, 1901 at Auburn penitentiary. Initially, Czolgosz’s family wanted the body. The warden convinced them that it would be a bad idea, that relic hunters would disturb his grave, or worse, that unscrupulous carnival promoters would want to display the body in traveling sideshows.

Just as Big Ben is the forgotten figure in the McKinley assassination saga, Leon Czolgosz is the least known of all presidential assassins. Prior to his execution Czolgosz met with two priests and said, “No. Damn them. Don’t send them here again. I don’t want them. And don’t you have any praying over me when I’m dead. I don’t want it. I don’t want any of their damned religion.” Czolgosz was electrocuted on October 29, 1901 at Auburn penitentiary. Initially, Czolgosz’s family wanted the body. The warden convinced them that it would be a bad idea, that relic hunters would disturb his grave, or worse, that unscrupulous carnival promoters would want to display the body in traveling sideshows.

His family agreed that the prison should take care of the funeral arrangements by giving the assassin a decent burial within the protection of the prison grounds. When Leon Czolgosz was buried in the Auburn prison cemetery, yards away from where he was executed, unbeknownst to the family, the decision was made to have his body destroyed. The local crematorium refused to undertake the job. So the assassin’s body was placed in a rough pine box and lowered into the ground which had been coated with quicklime. The lid was removed and two barrels of quicklime powder was caked on top of the body. Then sulfuric acid was poured on top of that followed by another two layers of quicklime.

His family agreed that the prison should take care of the funeral arrangements by giving the assassin a decent burial within the protection of the prison grounds. When Leon Czolgosz was buried in the Auburn prison cemetery, yards away from where he was executed, unbeknownst to the family, the decision was made to have his body destroyed. The local crematorium refused to undertake the job. So the assassin’s body was placed in a rough pine box and lowered into the ground which had been coated with quicklime. The lid was removed and two barrels of quicklime powder was caked on top of the body. Then sulfuric acid was poured on top of that followed by another two layers of quicklime.

Their intention was to make the anarchist’s body dematerialize. What the prison officials did not know was that when quicklime (calcium oxide) and sulfuric acid are combined, a chemical reaction occurs which creates an exterior coating best compared to plaster of paris. Since the shell is insoluble in water, the coating acts as a protective layer thus preventing further attack on the corpse by the acid. It is entirely possible that the body of Czolgosz was preserved in perpetuity accidentally.

Their intention was to make the anarchist’s body dematerialize. What the prison officials did not know was that when quicklime (calcium oxide) and sulfuric acid are combined, a chemical reaction occurs which creates an exterior coating best compared to plaster of paris. Since the shell is insoluble in water, the coating acts as a protective layer thus preventing further attack on the corpse by the acid. It is entirely possible that the body of Czolgosz was preserved in perpetuity accidentally.

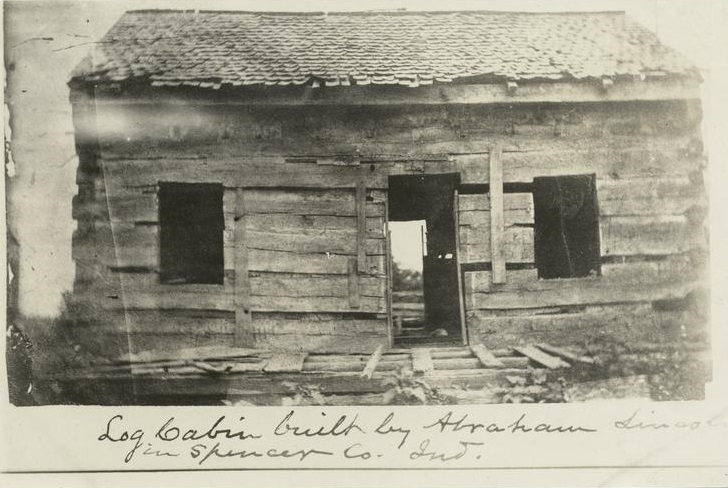

Eventually it was Abraham’s turn to hitch his old mare to the gristmill’s arm. As he tediously walked his horse round and round, he grew impatient at having wasted most of the morning already. He began to apply a hickory switch to the beast’s behind while shouting, “Git up, you old hussy; git up, you old hussy” to keep his horse moving at an accelerated pace. This tactic worked for a short time until the horse had had enough and, just as his young master clucked out the words “Git up”, the horse kicked backwards and hit the boy in the head with a rear hoof. Lincoln was knocked off his feet and into the air, landing some distance away where he came to rest bruised and bloodied. Noah Gordon rushed to the aid of the unconscious young man. Realizing the seriousness of the situation, Gordon picked the boy up and brought him in to his house, placing him on a nearby bed.

Eventually it was Abraham’s turn to hitch his old mare to the gristmill’s arm. As he tediously walked his horse round and round, he grew impatient at having wasted most of the morning already. He began to apply a hickory switch to the beast’s behind while shouting, “Git up, you old hussy; git up, you old hussy” to keep his horse moving at an accelerated pace. This tactic worked for a short time until the horse had had enough and, just as his young master clucked out the words “Git up”, the horse kicked backwards and hit the boy in the head with a rear hoof. Lincoln was knocked off his feet and into the air, landing some distance away where he came to rest bruised and bloodied. Noah Gordon rushed to the aid of the unconscious young man. Realizing the seriousness of the situation, Gordon picked the boy up and brought him in to his house, placing him on a nearby bed. Meanwhile, Dave Turnham, who had come to the mill with Abraham, ran the two miles to get Abraham’s father. Thomas Lincoln rushed to his wagon and lit out to the scene. The elder Lincoln, seeing his son’s grave condition, hauled the injured boy home and put him to bed where the young man remained prone and unconscious all night. Neighbors from the small, close knit community, including mill owner Noah Gordon, gathered at the Lincoln cabin believing Thomas Lincoln’s boy was close to death. The next morning one witness jumped from their seat, pointed and shouted, “Look he’s coming straight back from the dead!” Abraham was shaking and jerking from head to toe when he opened his eyes and finished his cadence from the day before by shouting “You old hussy”.

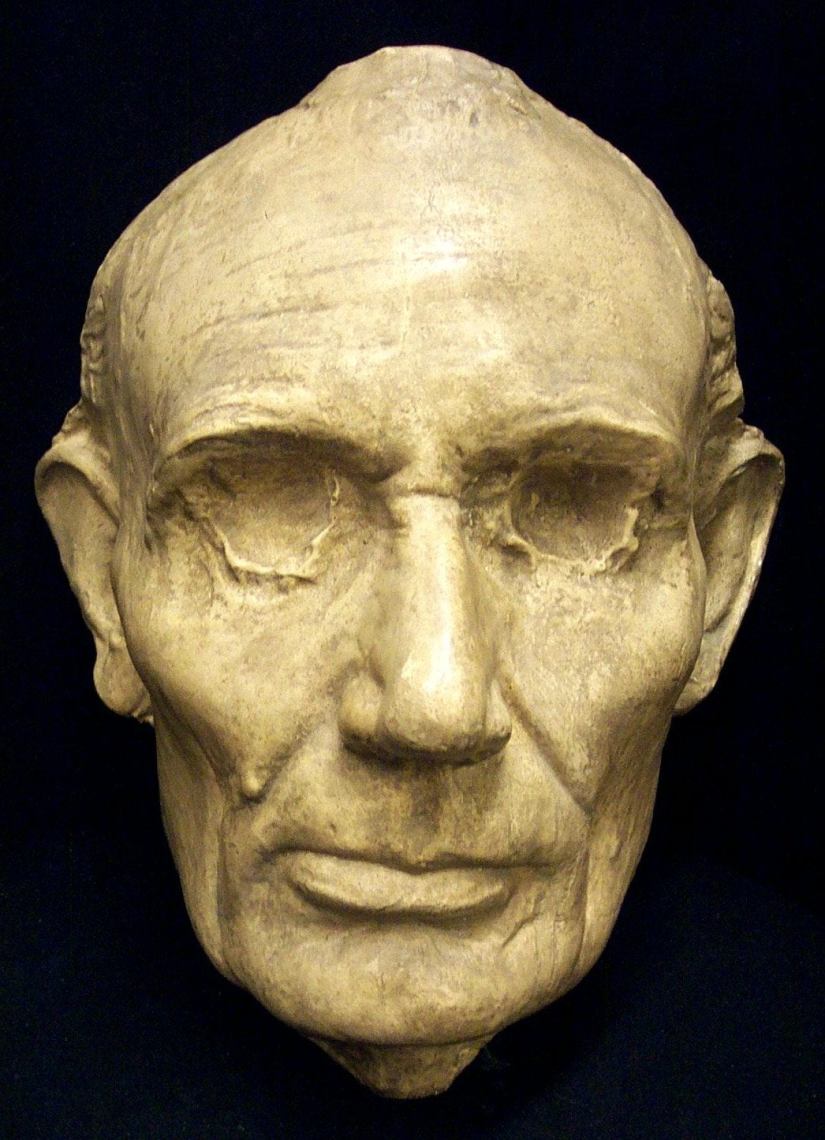

Meanwhile, Dave Turnham, who had come to the mill with Abraham, ran the two miles to get Abraham’s father. Thomas Lincoln rushed to his wagon and lit out to the scene. The elder Lincoln, seeing his son’s grave condition, hauled the injured boy home and put him to bed where the young man remained prone and unconscious all night. Neighbors from the small, close knit community, including mill owner Noah Gordon, gathered at the Lincoln cabin believing Thomas Lincoln’s boy was close to death. The next morning one witness jumped from their seat, pointed and shouted, “Look he’s coming straight back from the dead!” Abraham was shaking and jerking from head to toe when he opened his eyes and finished his cadence from the day before by shouting “You old hussy”. Lincoln’s contemporaries noticed that at times his left eye drifted upward independently of his right eye, a condition doctors diagnosed as “strabismus” but more derisively known as “Lazy Eye”. The resulting affliction results in the eyes failure to properly align with each other when looking straight ahead, particularly when trying to focus on an object. As proof, experts point to the best surviving evidence; two life masks of Lincoln. One a beardless portrait made in April of 1860 and the other, a bearded image made in February of 1865. Laser scans of both masks reveal an unusual degree of facial asymmetry. In short, the left side of Lincoln’s face was much smaller than the right, resulting in the double diagnosis of “hemifacial microsomia” compounded by “strabismus”. The defects join a long list of posthumously diagnosed ailments including smallpox, heart disease, bi-polar disorder and depression that doctors claimed afflicted Lincoln.

Lincoln’s contemporaries noticed that at times his left eye drifted upward independently of his right eye, a condition doctors diagnosed as “strabismus” but more derisively known as “Lazy Eye”. The resulting affliction results in the eyes failure to properly align with each other when looking straight ahead, particularly when trying to focus on an object. As proof, experts point to the best surviving evidence; two life masks of Lincoln. One a beardless portrait made in April of 1860 and the other, a bearded image made in February of 1865. Laser scans of both masks reveal an unusual degree of facial asymmetry. In short, the left side of Lincoln’s face was much smaller than the right, resulting in the double diagnosis of “hemifacial microsomia” compounded by “strabismus”. The defects join a long list of posthumously diagnosed ailments including smallpox, heart disease, bi-polar disorder and depression that doctors claimed afflicted Lincoln. According to a cadre of modern day medical historians, Gardner’s photo is worth a thousand words. Although modern neurologists admit that a positive diagnosis would require a complete examination of the living Lincoln, photographic evidence strongly supports their theory. The mule kick to the forehead undoubtedly fractured the skull at the point of impact, the size and depth of the depression attesting to the incident’s severity. In addition, the nerves behind the left eye were damaged by the violent snapping of the head and neck backward. That whiplash also caused several small hemorrhages in the brainstem resulting in the permanent ocular and facial effects and was likely responsible for Lincoln’s high pitched, rasping voice.

According to a cadre of modern day medical historians, Gardner’s photo is worth a thousand words. Although modern neurologists admit that a positive diagnosis would require a complete examination of the living Lincoln, photographic evidence strongly supports their theory. The mule kick to the forehead undoubtedly fractured the skull at the point of impact, the size and depth of the depression attesting to the incident’s severity. In addition, the nerves behind the left eye were damaged by the violent snapping of the head and neck backward. That whiplash also caused several small hemorrhages in the brainstem resulting in the permanent ocular and facial effects and was likely responsible for Lincoln’s high pitched, rasping voice. Yet another after effect of that boyhood mulekick was noticed by Josiah Crawford, a neighbor from Gentryville, Ind. who employed the boy Lincoln, loaned him books for study. Gentry liked to playfully needle the young railsplitter about the way he “stuck out” his lower lip while in deep concentration. When 35-year-old Lincoln returned to to make a speech in southern Indiana in 1844 for Henry Clay, Crawford noticed Abe’s lower lip still protruded abnormally. When Crawford asked what books he consulted before making the speech, Lincoln replied humorously, “I haven’t any. Sticking out my lip is all I need.”

Yet another after effect of that boyhood mulekick was noticed by Josiah Crawford, a neighbor from Gentryville, Ind. who employed the boy Lincoln, loaned him books for study. Gentry liked to playfully needle the young railsplitter about the way he “stuck out” his lower lip while in deep concentration. When 35-year-old Lincoln returned to to make a speech in southern Indiana in 1844 for Henry Clay, Crawford noticed Abe’s lower lip still protruded abnormally. When Crawford asked what books he consulted before making the speech, Lincoln replied humorously, “I haven’t any. Sticking out my lip is all I need.”

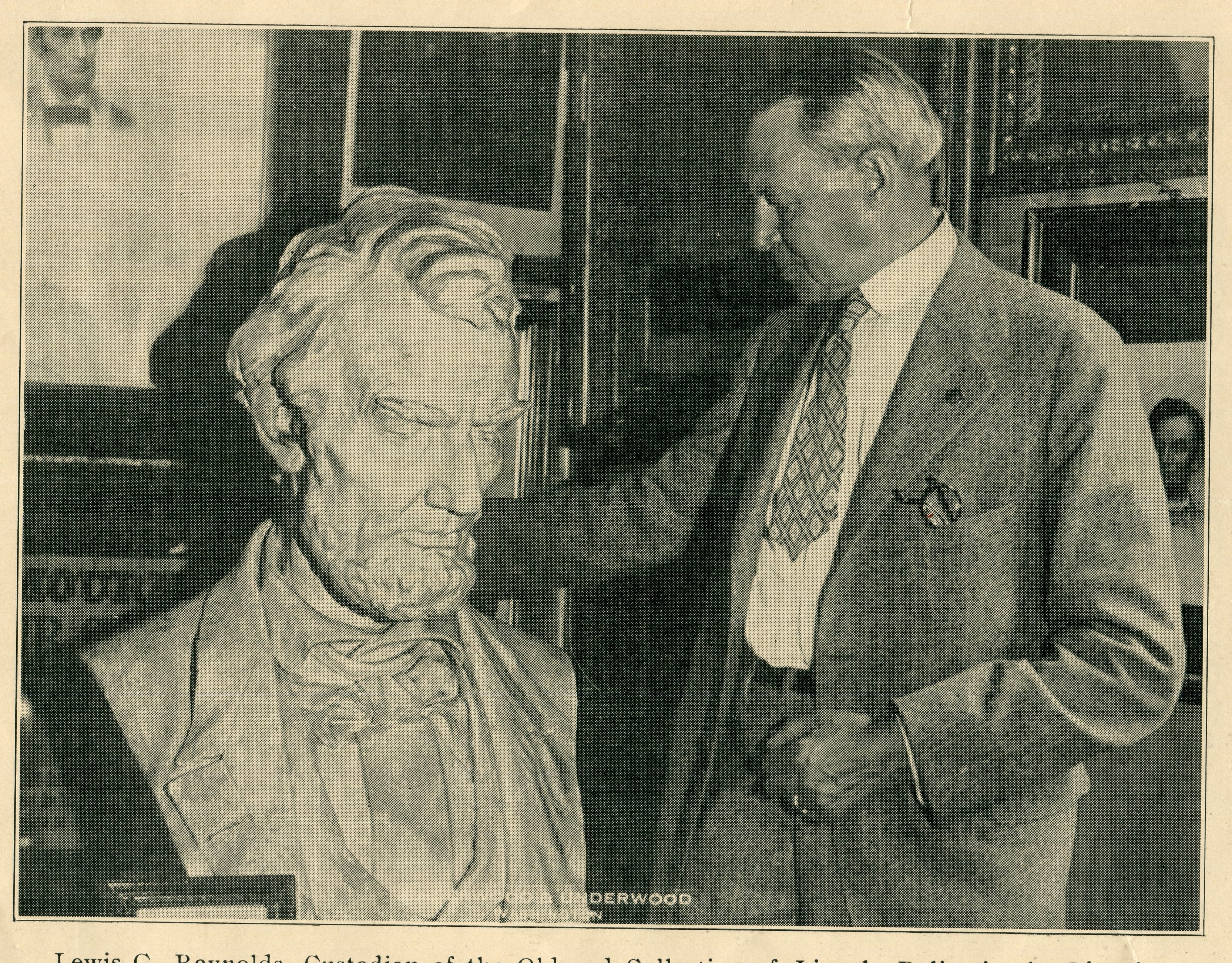

The Reynolds leaflet further reveals,”Father and mother were at Ford’s Theatre the night of the assassination, and although it was late when they returned home, the general excitement of the night had reached our neighborhood. The newsboys shrill cries of “Extra! Extra! President Lincoln Shot” had awakened everybody in the boarding house. I, too, was awake. Young as I was, I realized what dreadful thing had happened, and I lay wide-eyed in my little trundle bed while father and mother related to the others their personal story of the tragedy. Father, accompanied by several of the men guests, went back to the scene and did not return until after the fateful hour of 7:22 the next morning. I remember as clearly as though it were of yesterday, wearing a wide band of black around the sleeve of my bright plaid jacket, and, carried in father’s arms, of passing the somber catafalque in the rotunda of the Capitol, which inclosed (sic) all that was mortal of the beloved Lincoln. A few weeks later I witnessed the Grand Review of the Army – that wonderful spectacle of the returning boys in blue – which took several days in its passing.”

The Reynolds leaflet further reveals,”Father and mother were at Ford’s Theatre the night of the assassination, and although it was late when they returned home, the general excitement of the night had reached our neighborhood. The newsboys shrill cries of “Extra! Extra! President Lincoln Shot” had awakened everybody in the boarding house. I, too, was awake. Young as I was, I realized what dreadful thing had happened, and I lay wide-eyed in my little trundle bed while father and mother related to the others their personal story of the tragedy. Father, accompanied by several of the men guests, went back to the scene and did not return until after the fateful hour of 7:22 the next morning. I remember as clearly as though it were of yesterday, wearing a wide band of black around the sleeve of my bright plaid jacket, and, carried in father’s arms, of passing the somber catafalque in the rotunda of the Capitol, which inclosed (sic) all that was mortal of the beloved Lincoln. A few weeks later I witnessed the Grand Review of the Army – that wonderful spectacle of the returning boys in blue – which took several days in its passing.”

Two decades later, in 1960, the Richmond Palladium-Item newspaper profiled the widow of the former curator, offering new insight. The article is titled: “Local Woman Conducted Tours In House Where Lincoln Died.” It reveals, “Mrs. Reynolds and her husband lived on the second floor of the house at 516 Tenth Street, Washington, DC, at the time Mr. Reynolds was curator of the Oldroyd Lincoln Memorial collection. This was from 1928 through 1936. “I never heard anyone ask Mr. Reynolds a question about Mr. Lincoln he could not answer,” Mrs. Reynolds recalls. Her husband acquired the job as curator when he heard Oldroyd wanted to retire… “I have had visitors say to me doesn’t it give you a creepy feeling?” (sleeping in the house where Lincoln died.) Her answer was always “No.” To the reporter, she said, “I never had a creepy feeling. When I thought about it, it was just a feeling of awe and reverence.” Mr. Reynolds described the collection via radio from the Petersen house several times.“

Two decades later, in 1960, the Richmond Palladium-Item newspaper profiled the widow of the former curator, offering new insight. The article is titled: “Local Woman Conducted Tours In House Where Lincoln Died.” It reveals, “Mrs. Reynolds and her husband lived on the second floor of the house at 516 Tenth Street, Washington, DC, at the time Mr. Reynolds was curator of the Oldroyd Lincoln Memorial collection. This was from 1928 through 1936. “I never heard anyone ask Mr. Reynolds a question about Mr. Lincoln he could not answer,” Mrs. Reynolds recalls. Her husband acquired the job as curator when he heard Oldroyd wanted to retire… “I have had visitors say to me doesn’t it give you a creepy feeling?” (sleeping in the house where Lincoln died.) Her answer was always “No.” To the reporter, she said, “I never had a creepy feeling. When I thought about it, it was just a feeling of awe and reverence.” Mr. Reynolds described the collection via radio from the Petersen house several times.“

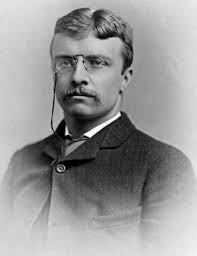

Most Americans remember President William McKinley solely for the way he died. His image a milquetoast chief executive from the age of American Imperialism who was at the helm for the dawn of the 20th century. McKinley’s ordinary appearance belied the fact that he was the last president to have served in the American Civil War and the only one to have started the war as an enlisted soldier. It is long forgotten that McKinley led the nation to victory in the Spanish-American War, protected American industry by raising tariffs, and kept the nation on the gold standard by rejecting free silver. Most notably, his assassination at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York unleashed the central figure who would come to personify the new century; his Vice-President Teddy Roosevelt.

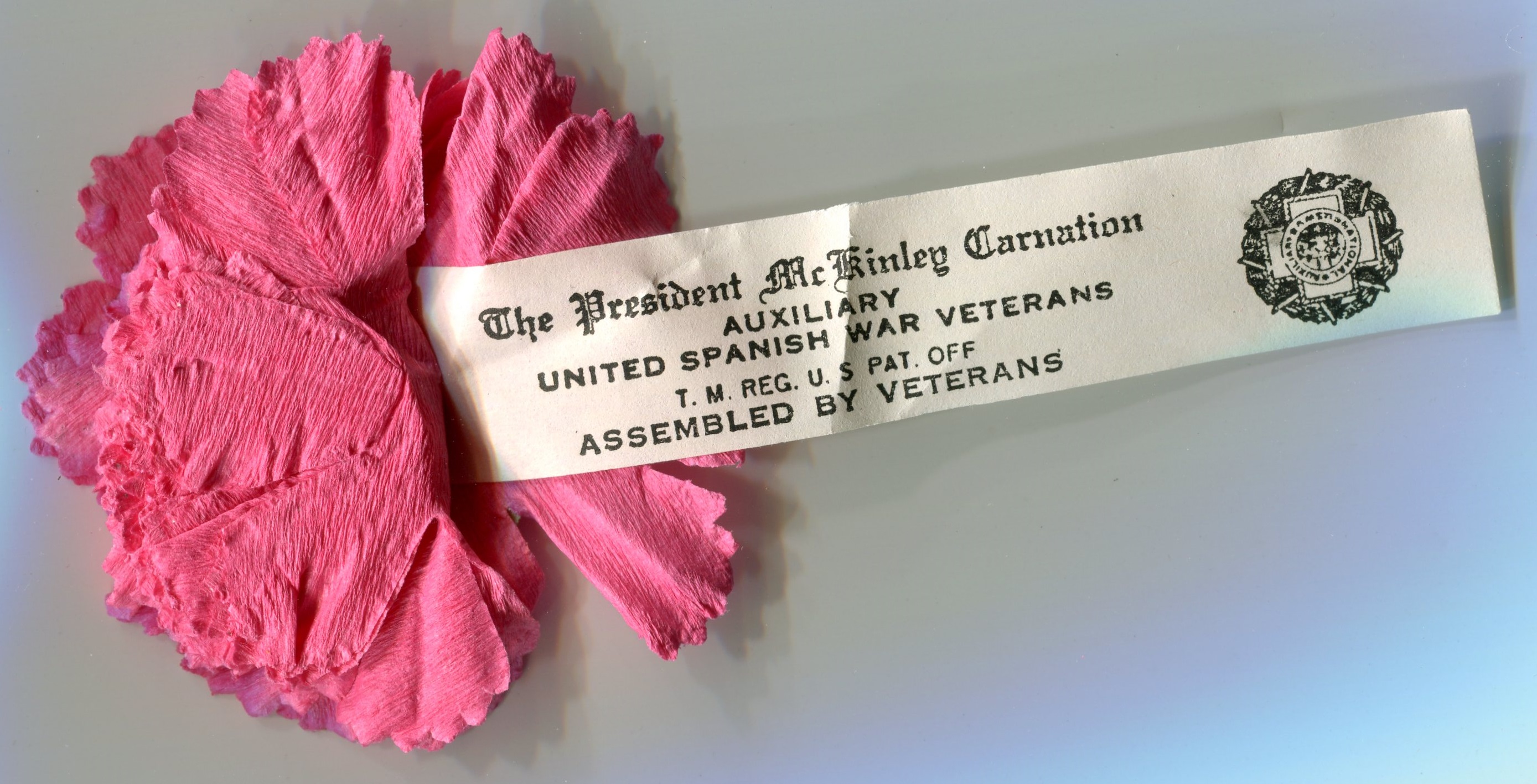

Most Americans remember President William McKinley solely for the way he died. His image a milquetoast chief executive from the age of American Imperialism who was at the helm for the dawn of the 20th century. McKinley’s ordinary appearance belied the fact that he was the last president to have served in the American Civil War and the only one to have started the war as an enlisted soldier. It is long forgotten that McKinley led the nation to victory in the Spanish-American War, protected American industry by raising tariffs, and kept the nation on the gold standard by rejecting free silver. Most notably, his assassination at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York unleashed the central figure who would come to personify the new century; his Vice-President Teddy Roosevelt. McKinley’s favorite flower was a red carnation. He displayed his affection by wearing one of the bright red florets in his lapel every day. The carnation boutonnière soon became McKinley’s personal trademark. As President, bud vases filled with red carnations were conspicuously placed around the White House (known as the “Executive Mansion” back then). Whenever a guest visited the President, McKinley’s custom was to remove the carnation from his lapel and present it to the star-struck visitor. For men, he would often place the souvenir blossom into the lapel himself and suggest that it be given to an absent wife, mother, or child. Afterward, he would replace his boutonnière with another from a nearby vase and repeat the transfer again and again for the rest of the day. McKinley was superstitious about these carnations, believing that they brought good luck to both him and his recipient.

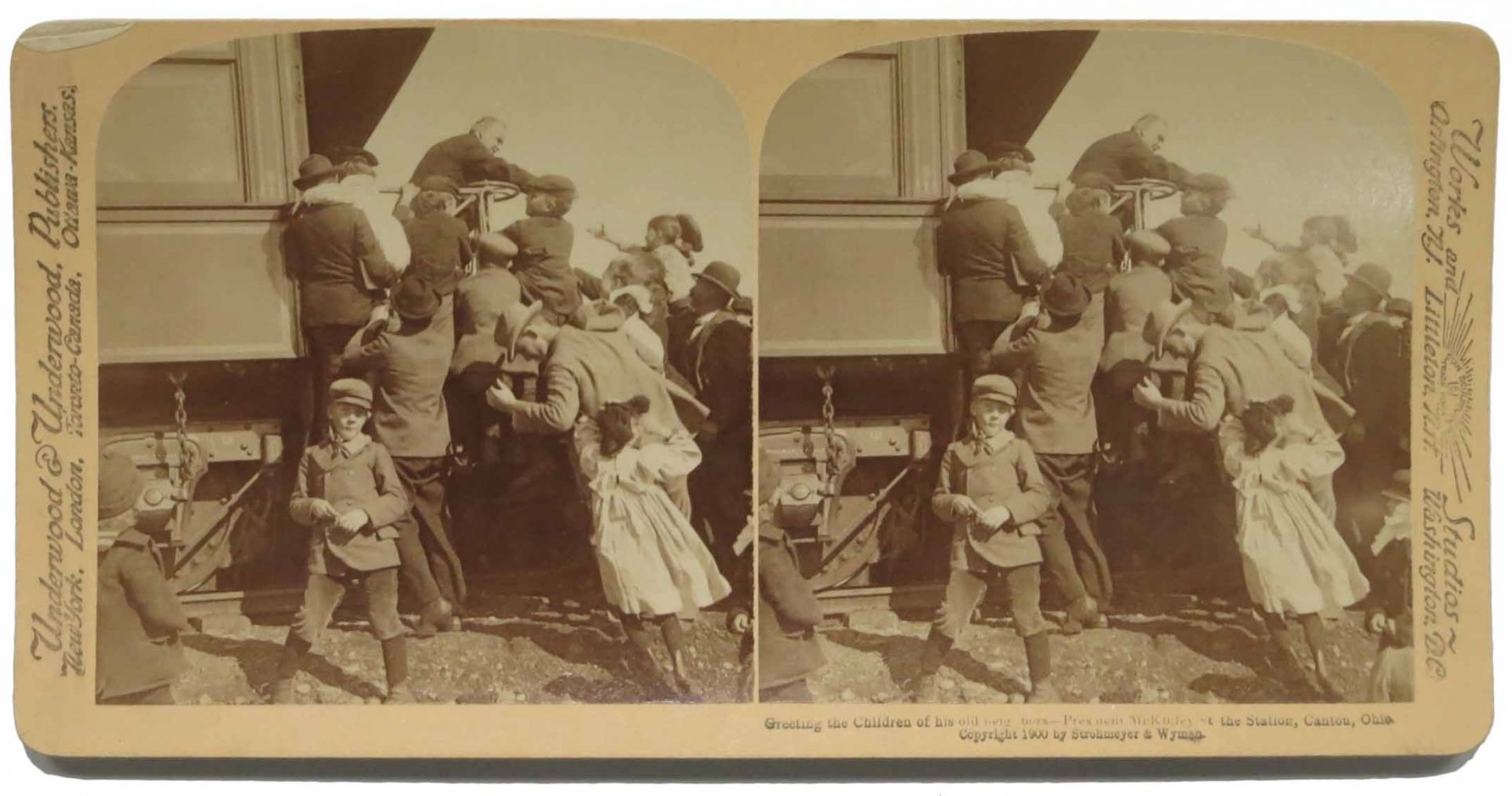

McKinley’s favorite flower was a red carnation. He displayed his affection by wearing one of the bright red florets in his lapel every day. The carnation boutonnière soon became McKinley’s personal trademark. As President, bud vases filled with red carnations were conspicuously placed around the White House (known as the “Executive Mansion” back then). Whenever a guest visited the President, McKinley’s custom was to remove the carnation from his lapel and present it to the star-struck visitor. For men, he would often place the souvenir blossom into the lapel himself and suggest that it be given to an absent wife, mother, or child. Afterward, he would replace his boutonnière with another from a nearby vase and repeat the transfer again and again for the rest of the day. McKinley was superstitious about these carnations, believing that they brought good luck to both him and his recipient. One account alleges that McKinley’s “Genus Dianthus” custom began early in his presidency when an aide brought his two sons to the White House to meet the President. McKinley, who loved children dearly, presented his carnation to the older boy. Seeing the disappointment in the younger boy’s face, the President deftly retrieved a replacement carnation and pinned it on his own lapel. Here the flower remained for a few moments before he removed it and gave to the younger child, explaining “this way you both can have a carnation worn by the President.”

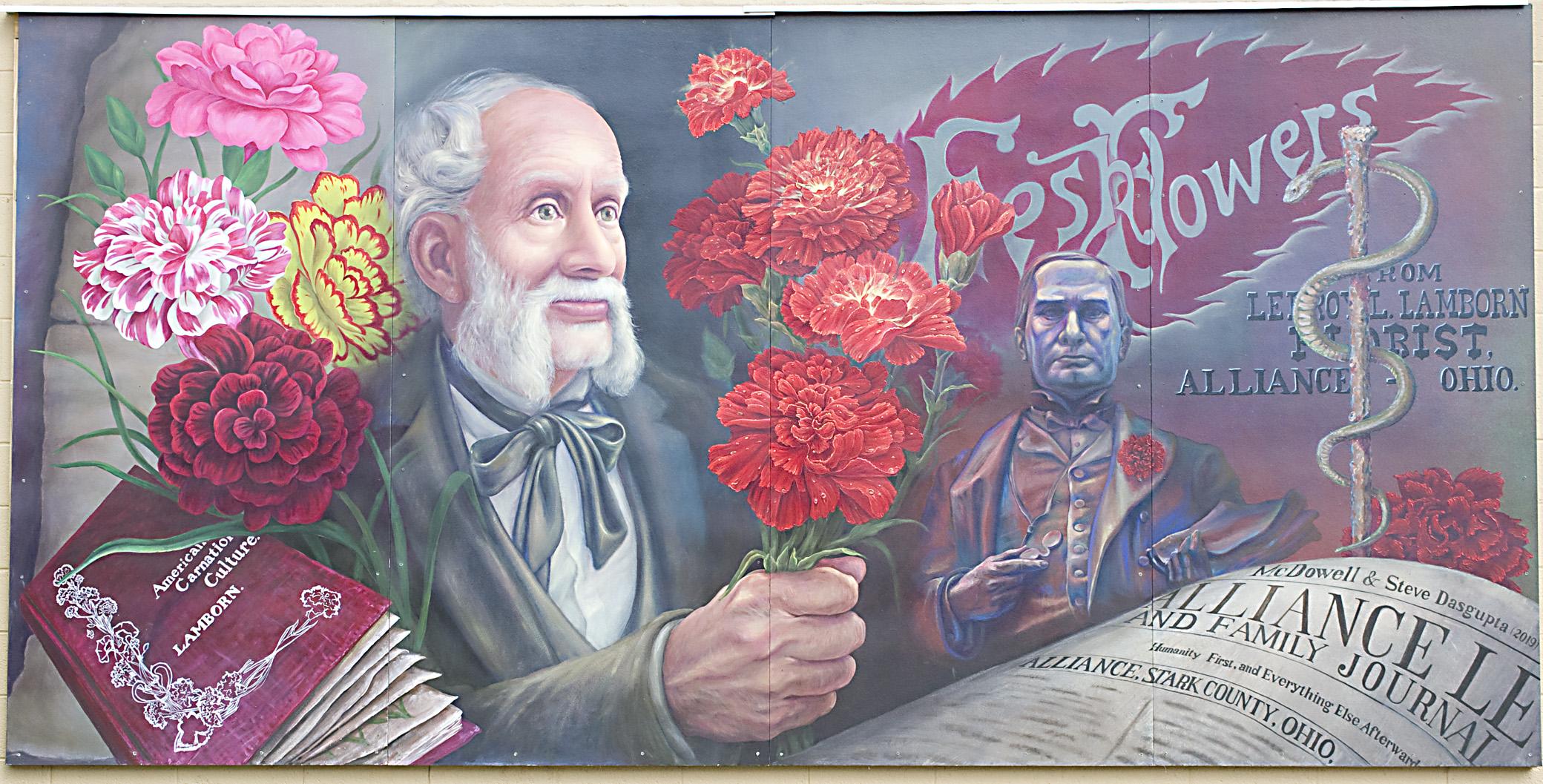

One account alleges that McKinley’s “Genus Dianthus” custom began early in his presidency when an aide brought his two sons to the White House to meet the President. McKinley, who loved children dearly, presented his carnation to the older boy. Seeing the disappointment in the younger boy’s face, the President deftly retrieved a replacement carnation and pinned it on his own lapel. Here the flower remained for a few moments before he removed it and gave to the younger child, explaining “this way you both can have a carnation worn by the President.” However, McKinley’s ubiquitous floral tradition can be traced to the election of 1876, when he was running for a seat in Congress. His opponent, Dr. Levi Lamborn, of Alliance, Ohio, was an accomplished amateur horticulturist famed for developing a strain of vivid scarlet carnations he dubbed “Lamborn Red.” Dr. Lamborn presented McKinley with a “Lamborn Red” boutonniere before their debates. After he won the election, McKinley viewed the red carnation as a good luck charm. He wore one on his lapel regularly and soon began his custom of presenting them to visitors. He wore one during his fourteen years in Congress, his two gubernatorial wins and both 1896 and 1900 presidential campaigns.

However, McKinley’s ubiquitous floral tradition can be traced to the election of 1876, when he was running for a seat in Congress. His opponent, Dr. Levi Lamborn, of Alliance, Ohio, was an accomplished amateur horticulturist famed for developing a strain of vivid scarlet carnations he dubbed “Lamborn Red.” Dr. Lamborn presented McKinley with a “Lamborn Red” boutonniere before their debates. After he won the election, McKinley viewed the red carnation as a good luck charm. He wore one on his lapel regularly and soon began his custom of presenting them to visitors. He wore one during his fourteen years in Congress, his two gubernatorial wins and both 1896 and 1900 presidential campaigns.

After his second inauguration on March 4, 1901, William and Ida McKinley departed on a six-week train trip of the country. The McKinleys were to travel through the South to the Southwest, and then up the Pacific coast and back east again, to conclude with a visit to the Buffalo Exposition on June 13, 1901. However, the First Lady fell ill in California, causing her husband to limit his public events and cancel a series of planned speeches. The First family retreated to Washington for a month and then traveled to their Canton, Ohio home for another two months, delaying the Expo trip until September.

After his second inauguration on March 4, 1901, William and Ida McKinley departed on a six-week train trip of the country. The McKinleys were to travel through the South to the Southwest, and then up the Pacific coast and back east again, to conclude with a visit to the Buffalo Exposition on June 13, 1901. However, the First Lady fell ill in California, causing her husband to limit his public events and cancel a series of planned speeches. The First family retreated to Washington for a month and then traveled to their Canton, Ohio home for another two months, delaying the Expo trip until September.

As McKinley fell backwards into the arms of his aides, members of the crowd immediately attacked Czolgosz. McKinley said, “Go easy on him, boys.” McKinley urged his aides to break the news gently to Ida, and to call off the mob that had set on Czolgosz, thereby saving his assassin’s life. McKinley was taken to the Exposition aid station, where the doctor was unable to locate the second bullet. Ironically, although a newly developed X-ray machine was displayed at the fair, doctors were reluctant to use it on the President because they did not know what side effects. Worse yet, the operating room at the exposition’s emergency hospital did not have any electric lighting, even though the exteriors of many of the buildings were covered with thousands of light bulbs. Amazingly, doctors used a pan to reflect sunlight onto the operating table as they treated McKinley’s wounds.

As McKinley fell backwards into the arms of his aides, members of the crowd immediately attacked Czolgosz. McKinley said, “Go easy on him, boys.” McKinley urged his aides to break the news gently to Ida, and to call off the mob that had set on Czolgosz, thereby saving his assassin’s life. McKinley was taken to the Exposition aid station, where the doctor was unable to locate the second bullet. Ironically, although a newly developed X-ray machine was displayed at the fair, doctors were reluctant to use it on the President because they did not know what side effects. Worse yet, the operating room at the exposition’s emergency hospital did not have any electric lighting, even though the exteriors of many of the buildings were covered with thousands of light bulbs. Amazingly, doctors used a pan to reflect sunlight onto the operating table as they treated McKinley’s wounds. McKinley drifted in and out of consciousness all day. By evening, McKinley himself knew he was dying, “It is useless, gentlemen. I think we ought to have prayer.” Relatives and friends gathered around the deathbed. The First Lady sobbed over him, “I want to go, too. I want to go, too.” Her husband replied, “We are all going, we are all going. God’s will be done, not ours” and with final strength put an arm around her. Some reports claimed that he also sang part of his favorite hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee” while others claim that the First Lady sang it softly to him. At 2:15 a.m. on September 14, President McKinley died. Czolgosz was sentenced to death and executed by electric chair on October 29, 1901.

McKinley drifted in and out of consciousness all day. By evening, McKinley himself knew he was dying, “It is useless, gentlemen. I think we ought to have prayer.” Relatives and friends gathered around the deathbed. The First Lady sobbed over him, “I want to go, too. I want to go, too.” Her husband replied, “We are all going, we are all going. God’s will be done, not ours” and with final strength put an arm around her. Some reports claimed that he also sang part of his favorite hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee” while others claim that the First Lady sang it softly to him. At 2:15 a.m. on September 14, President McKinley died. Czolgosz was sentenced to death and executed by electric chair on October 29, 1901. Loyal readers will recognize my affinity for objects and will not be surprised by the query, “What became of that assassination carnation?” In an article for the Massillon, Ohio Daily Independent newspaper on Sept. 7, 1984, Myrtle Ledger Krass, the 12-year-old-girl to whom the President gave his lucky flower moments before he was killed, reported that the McKinley’s carnation was pressed and kept in the family Bible. Myrtle, at the time a well-known painter living in Largo, Florida, explained how, many years later while moving, “The old Bible had been put away for years, when I took it out to wrap it for moving, it just crumbled in my hand. Just fell away to nothing.”

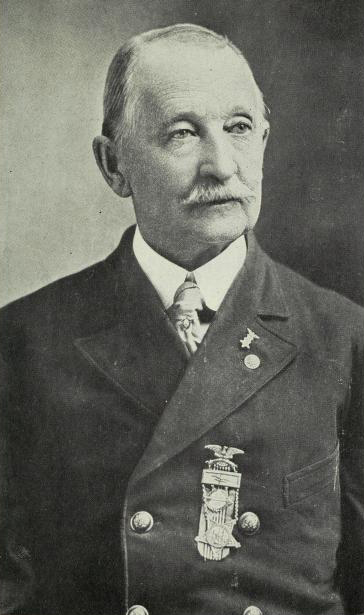

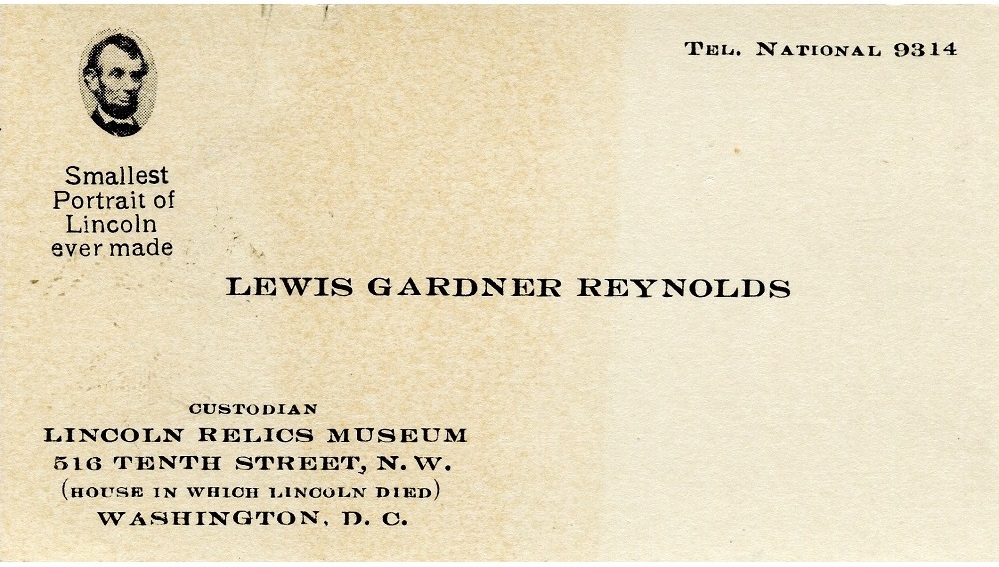

Loyal readers will recognize my affinity for objects and will not be surprised by the query, “What became of that assassination carnation?” In an article for the Massillon, Ohio Daily Independent newspaper on Sept. 7, 1984, Myrtle Ledger Krass, the 12-year-old-girl to whom the President gave his lucky flower moments before he was killed, reported that the McKinley’s carnation was pressed and kept in the family Bible. Myrtle, at the time a well-known painter living in Largo, Florida, explained how, many years later while moving, “The old Bible had been put away for years, when I took it out to wrap it for moving, it just crumbled in my hand. Just fell away to nothing.” In 1902, Lewis Gardner Reynolds (born in 1858 in Bellefontaine, Ohio) found himself in Buffalo on business on the first anniversary of McKinley’s death. While there he found that the mayor of Buffalo had declared the day a legal holiday. Gardner recalled, “without thinking at the time that I was doing something that would become a national custom, I purchased a pink carnation which I placed in the buttonhole of my coat after tying a small piece of black ribbon on it. As I went through Buffalo I explained to questioners the reason for the flower and the black ribbon. Many of those who questioned me followed my example.” On his return to Ohio, he explained to his friend Senator Mark Hannah what he had done in Buffalo. Later, in Cleveland, Reynolds met with Hannah and Governor Myron T. Herrick. Soon plans were made to celebrate Jan. 29, the anniversary of McKinley’s birth, as “Carnation Day.”

In 1902, Lewis Gardner Reynolds (born in 1858 in Bellefontaine, Ohio) found himself in Buffalo on business on the first anniversary of McKinley’s death. While there he found that the mayor of Buffalo had declared the day a legal holiday. Gardner recalled, “without thinking at the time that I was doing something that would become a national custom, I purchased a pink carnation which I placed in the buttonhole of my coat after tying a small piece of black ribbon on it. As I went through Buffalo I explained to questioners the reason for the flower and the black ribbon. Many of those who questioned me followed my example.” On his return to Ohio, he explained to his friend Senator Mark Hannah what he had done in Buffalo. Later, in Cleveland, Reynolds met with Hannah and Governor Myron T. Herrick. Soon plans were made to celebrate Jan. 29, the anniversary of McKinley’s birth, as “Carnation Day.”

Today, the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus continues observing Red Carnation Day every January 29 by installing a small display honoring the assassinated President. Last year, the Statehouse Museum Shop and on-site restaurant offered special discounts to anyone wearing a red carnation or dressed in scarlet on that day. Yes, the sentimental association of the carnation with McKinley’s memory is due to Lewis Gardner Reynolds.

Today, the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus continues observing Red Carnation Day every January 29 by installing a small display honoring the assassinated President. Last year, the Statehouse Museum Shop and on-site restaurant offered special discounts to anyone wearing a red carnation or dressed in scarlet on that day. Yes, the sentimental association of the carnation with McKinley’s memory is due to Lewis Gardner Reynolds.

That Friday, President Richard Nixon refused to honor a subpoena by the Senate Watergate Committee to hand over tape recordings and documents during the impeachment proceedings. It would prove to be the beginning of the end of his Presidency and would lead to his resignation in disgrace eight months later. In Nixon’s hometown of San Clemente, California, the newspaper proclaimed, “President Nixon declined flatly today to produce any of the more than 500 documents subpoenaed by the Senate Watergate committee, branding the request “an overt attempt to intrude into the executive office to a degree that constitutes an unconstitutional usurpation of power.”

That Friday, President Richard Nixon refused to honor a subpoena by the Senate Watergate Committee to hand over tape recordings and documents during the impeachment proceedings. It would prove to be the beginning of the end of his Presidency and would lead to his resignation in disgrace eight months later. In Nixon’s hometown of San Clemente, California, the newspaper proclaimed, “President Nixon declined flatly today to produce any of the more than 500 documents subpoenaed by the Senate Watergate committee, branding the request “an overt attempt to intrude into the executive office to a degree that constitutes an unconstitutional usurpation of power.” In a letter addressed to committee chairman (North Carolina Senator Sam J. Ervin Jr. Democrat), Nixon refused to supply recordings of his Oval Office conversations or any related written materials. The letter arrived on Capitol Hill three hours past the deadline set by the committee to hand over the documents. Speaking to reporters at the Western White House, “La Casa Pacifica” in San Clemente, Deputy Presidential Press Secretary Gerald L. Warren declined to say what his boss’s next move would be, or to comment on Federal Judge John J. Sirica’s threat of contempt-of-court action against Nixon.

In a letter addressed to committee chairman (North Carolina Senator Sam J. Ervin Jr. Democrat), Nixon refused to supply recordings of his Oval Office conversations or any related written materials. The letter arrived on Capitol Hill three hours past the deadline set by the committee to hand over the documents. Speaking to reporters at the Western White House, “La Casa Pacifica” in San Clemente, Deputy Presidential Press Secretary Gerald L. Warren declined to say what his boss’s next move would be, or to comment on Federal Judge John J. Sirica’s threat of contempt-of-court action against Nixon.

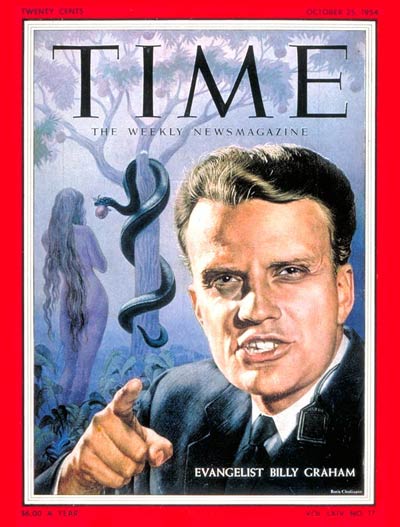

Graham instead remained more general in his remarks, even eschewing humorous suggestions by his inner circle that he preach on tithing in light of recent disclosures that Nixon reported less than $14,000 in total charitable contributions while reporting nearly $1 million over the past four years. The closest the evangelist came to the alleged scandal came when he spoke out on social justice. “We must remake the unjust structures that have taken advantage of the powerless and broken the hearts of the poor and dispossessed,” he asserted. But, he cautioned, “we all admit that we need some sweeping social reforms—and in true repentance we must determine to do something about it—our greatest need is a change in the heart.”

Graham instead remained more general in his remarks, even eschewing humorous suggestions by his inner circle that he preach on tithing in light of recent disclosures that Nixon reported less than $14,000 in total charitable contributions while reporting nearly $1 million over the past four years. The closest the evangelist came to the alleged scandal came when he spoke out on social justice. “We must remake the unjust structures that have taken advantage of the powerless and broken the hearts of the poor and dispossessed,” he asserted. But, he cautioned, “we all admit that we need some sweeping social reforms—and in true repentance we must determine to do something about it—our greatest need is a change in the heart.”