Original publish date: June 7, 2013

Original publish date: June 7, 2013

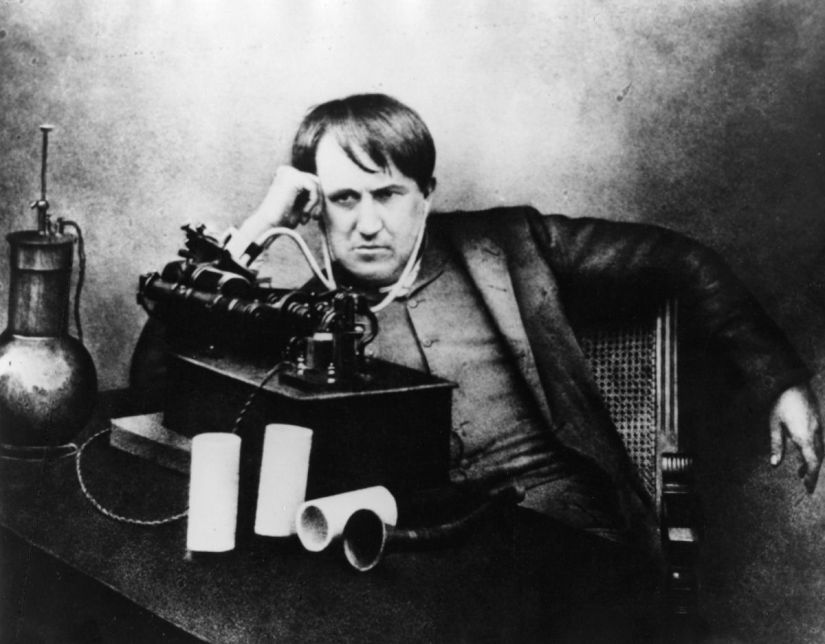

The most famous and prolific inventor of all time, Thomas Alva Edison died over 85 years ago. His tremendous influence on modern life remains unchallenged by any other American, living or dead. Edison’s inventions include the light bulb, the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and vast improvements on the telegraph and telephone. In his 84 years, he acquired an astounding 1,093 patents, a record that eclipses all other inventors. It is a tribute to his genius as an inventor, businessman, and promoter that many believe we owe our way of life to his ideas. But, did you know that what Edison himself considered his first invention was created right here in Indianapolis?

Thomas Alva Edison was born on February 11, 1847, in Milan, Ohio. Known as “Al” in his youth, Edison was the youngest, and sickliest, of seven children, only four of which survived to adulthood. In search of a better life for his family, Edison’s father Sam moved to Port Huron, Michigan, in 1854, where he worked in the lumber business.

“Al” was a poor student fascinated with mechanical things and chemical experiments instead of book learning. When a schoolmaster called Edison “addled,” his furious mother took him out of the school and began to home school the young inventor. Edison said many years later, “My mother was the making of me. She was so true, so sure of me, and I felt I had some one to live for, some one I must not disappoint.”

The home schooling schedule made his life more flexible and, like most boys of his day, Edison began working at the age of 11. His first job was helping in the family garden, but as “hoeing corn in a hot sun is unattractive,” he found other work when the opportunity arose. That opportunity came in late 1859 when the Grand Trunk Railroad was extended through Port Huron to Detroit. Edison talked his way into a job as a “candy butcher,” selling candy, newspapers, and magazines to the passengers. In that position he soon showed an entrepreneurial flair. While he was away working on the train, he employed boys to sell vegetables and magazines in Port Huron for him. With that money, he bought a printing press, which he used to start up the Grand Trunk Herald, the first newspaper published on a train. He wrote the articles and printed and sold the newspapers to passengers on the train. He spent his free time reading scientific books and technical manuals, most left behind by the passengers on the trains. In fact, passengers would often leave their reading materials behind and Al would resell them to the next group of travelers over-and-over again.

During layovers in the “Motor City”, Edison continued his education by visiting the Detroit Public Library to consult science books before returning to the train to perform chemistry experiments in the baggage car. That is, until an accidental fire forced him to stop his on board experiments. In 1859 12-year-old Edison lost almost all his hearing. Several theories have been advanced as to what caused his hearing loss. Some attribute it to the aftereffects of scarlet fever contracted as a child. Edison himself blamed it on a conductor who lifted the lad by his ears after that fire in the baggage car. However, he never let his disability discourage him. Instead, since it made it easier for him to concentrate on his experiments and research, he treated it as an asset.

No doubt his hearing loss caused Edison to retreat more into reading and personal solitude. Along the way, he picked up the rudiments of telegraphy. His first big break came quite by accident, literally. In 1862, 15-year-old Edison rescued the toddler son of telegraph operator James MacKenzie from the path of a rolling freight car. MacKenzie rewarded him by giving him lessons. After practicing intensively all summer, Edison took a part-time telegraph job in Port Huron.

The Civil War was raging, and when the battle of Shiloh was reported in the Detroit Free Press in early April 1862, Edison talked the editor into giving him extra copies on credit and then telegraphed the headlines ahead to the train’s scheduled stops. The crowds were so large and the demand for the papers so great that he steadily increased the price at each station, selling all the papers at a handsome profit. It is clear that young Al learned a valuable lesson about the power of the telegraph and the press. He learned quickly that knowledge was power and power was money. By the time he was sixteen, Edison was proficient enough to work as a telegrapher full time.

Within a year Edison had embarked on a four-year stint as an itinerant telegrapher, a path followed by many ambitious, technically oriented young men. During those years he advanced to the front rank of telegraphers, becoming an expert receiver known for his clear, rapid handwriting. His proficiency elevated Edison to the upper echelon of elite press-wire operators, the men who handled the lengthy, important news dispatches. A highly esteemed, much desired position during the Civil War. Although still a teenager, he mixed and mingled with much older journalists and editors, frequenting their offices and engaging in their conversations that would often last into the wee hours of the morning. Some of his fellow operators would become newspaper reporters and Al’s close association with them them would, in time, help push Edison into the public eye.

Edison worked in many of the larger cities of the Midwest, then considered to be the epicenter of cutting edge technical advances in the United States. Like all operators, Edison had to maintain his instruments and the batteries that powered the lines. He studied them and thought about ways to improve them, experimenting with discarded, outdated and broken instruments. He purchased a small lathe and some other tools. For two months in early 1864, Edison had become a “tramp telegrapher”, the term used to describe a young “gun for hire” telegraph operator in search of the highest bidder. He worked in Fort Wayne before moving to Indianapolis in the Fall-Winter of 1864.

For a few months in 1864, the Indianapolis Union Station Depot was the place of employment for the young inventor. Thomas Edison arrived in the Hoosier Capitol City as a seventeen-and-a-half year old second-class telegraph operator for Western Union. He had bounced along, moving through larger and larger cities, using his telegraphing jobs mostly as laboratories for his experiments. He usually left these jobs in a hurry after being dismissed when the budding inventor became distracted and failed to send and receive messages properly. The fact that he had no trouble landing jobs in new cities speaks to the demand for telegraphers during wartime.

The telegraph revolutionized communications in the United States and the job of telegraph operator became one of the highest paid new professions. Young Edison imagined a life of glamorous freedom and excitement. In truth, most of the men who actually made their living this way, although highly skilled, were undisciplined with a variety of problems, unhappy home lives and physical detriments, usually alcoholism.

Edison, on the other hand, was greatly helped by his experience as a telegrapher. He used the long stretches of solitude and inactivity between messages to think and tinker with his experiments. Not unlike the modern day computer programmer, the telegraph operator’s job involved challenges, problem solving, and innovation. And in Indianapolis, Edison was first introduced to Western Union, a company whose ruthless bargaining, price cuts, and slash-and-burn business tactics eventually made them the top telegraph service in the U.S. Edison picked up many successful business practices from Western Union and, in time, would become known for his own ruthless tactics.

It was at Union Station that he developed his first invention, which he called the “automatic repeater telegraph”, a device used to record incoming telegraph signals and replay them at any desired rate. This allowed him to transcribe the often rapid-fire messages sent via the news wires. This skill meant a higher pay grade for him.

The legend surrounding Edison’s end of tenure at Indianapolis Union Station is told in many forms and fashions, making it hard to separate fact from fiction. A thumbnail version might go like this: It was November 8, 1864. Abraham Lincoln was being challenged for a second term by the flamboyant Union General whom Lincoln had hired, and fired, twice during the Civil War, George McClellan, a Democrat. The outcome was far from certain and northerners perched on the edge of their seats waiting to hear the results of this important wartime election. State-by-state the votes were counted and the telegraph wires were hot with returns.

Young Edison thought this would be the perfect time to unwrap, uncoil and unleash his new invention, which he named the “Morse repeater.” The invention consisted of two separate telegraph machines that Al had “jerry-rigged” together, one to transcribe the message and the other to save it. The device slowed down the incoming messages so transcribing operators could process the content more precisely. The machine worked fine, at first. Things quickly broke down and soon, quite literally, sparks began to fly. Seems the results were coming in too fast for even two machines to keep track of. Edison’s boss was infuriated by what he viewed as yet another Cockamamie gadget and reportedly fired the young inventor on the spot. Edison packed up his supplies and quickly moved to Cincinnati where he soon developed a more successful data storage device. Eventually, this device would become known by all as the phonograph.

At one time, Union Station once had a plaque somewhere inside it’s walls honoring Edison’s brief service in our city. But I have been unable to confirm that it still exists. Seems that the plaque, like Edison’s time in the Circle City, has been lost and forgotten.

Original publish date: September 11, 2015

Original publish date: September 11, 2015 Original publish date: September 10, 2015

Original publish date: September 10, 2015 Original publish date: February 27, 2017

Original publish date: February 27, 2017 Original publish date: August 7, 2014

Original publish date: August 7, 2014