Original publish date July 18, 2024. https://weeklyview.net/2024/07/18/charlotte-corday/

This 24-hour news cycle world can be exhausting. As I write this article, we stand at 120 days and counting until our next Presidential election. We are constantly reminded that this will be the most important election in the history of our country and that the end of Democracy is on the line. Since I spend most of my time buried in history of one sort or another, a phrase from the ancients runs on a loop in my head; “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.” My idiomatic paraphrase is a Biblical verse: Ecclesiastes 1:9, “The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.”

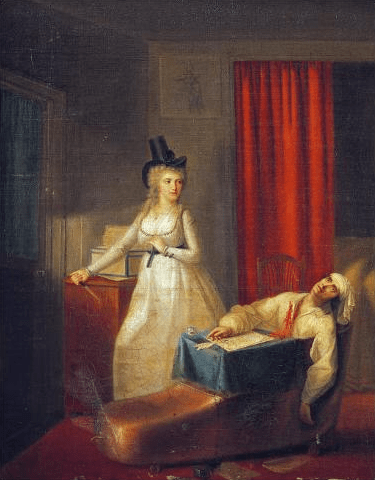

This is the story of Charlotte Corday. It is complicated, shocking, and gory, and does not end well. Her act is immortalized in one of the most famous images from the French Revolution: The Death of Marat, a 1793 painting by Jacques-Louis David. The painting depicts Jean-Paul Marat lying dead in his bathtub after his assassination by Corday on July 13, 1793. It is considered a masterpiece of the highest order and the first modernist work to express just how bad politics can be. The original painting is at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium with a replica on display at the Louvre.

Marie-Anne Charlotte de Corday d’Armont (July 27, 1768 – 17 July 1793) was born to an aristocratic family in Normandy, France. Corday held Marat responsible for the September Massacres of 1792, a series of executions of prisoners in Paris during the French Revolution. Over 1600 people, most of whom were non-violent political prisoners, were dragged from their cells and killed by guillotine at the hands of the “Committee of Surveillance of the Commune” led by the Montagnards, who advocated a more radical approach to the revolution. As The French Revolution radicalized further and headed towards terror, Corday began to sympathize with the Girondins. The Girondins supported democratic reforms and a strong legislative branch at the expense of much weaker executive and judiciary branches. She regarded the Girondins as a movement that would ultimately save France and that the Revolution was in jeopardy due to the radical course taken by Marat and the Montagnards.

On July 13, 1793, Corday traveled to Paris to assassinate Marat. He was not hard to find. Marat was suffering from a debilitating skin disease that left him nearly constantly confined to a bathtub to ease his suffering. Marat had always been a sickly man whom contemporaries described as “short in stature, deformed in person, and hideous in face.” The nature of his skin disease has been debated for centuries, some claimed it was syphilis, though most experts have identified it as “Dermatitis herpetiformis” a chronic, intensely itchy, blistering skin manifestation commonly known as celiac disease, a rash affecting about 10 percent of the population. Marat’s condition, which he had been suffering from for three years, was exacerbated by extreme weight loss, emaciation, and diminished strength. Marat stewed in a soup of various minerals and medicines with a bandana soaked in vinegar wrapped around his head. Marat sat upon a linen sheet for modesty, with the dry corners covering his back and bare shoulders, a board straddled the tub from rim to rim which served as a writing desk.

Corday is described on her passport as “five feet and one inch…curly auburn hair, eyes gray, forehead high, mouth medium size, chin dimpled, and an oval face”. Based solely on her appearance, Corday was the unlikeliest of assassins. On July 9, 1793, Corday arrived in Paris and took a room at the Hôtel de Providence. She bought a kitchen knife with a 6-inch blade. During the next few days, she wrote a detailed manifesto explaining her motives for assassinating Marat. At noon on July 13, she arrived at Marat’s home claiming to know about a planned Girondist uprising but was turned away. She returned that evening and was admitted. Their interview lasted fifteen minutes. From his bathtub, Marat wrote down the names of the Girondins as Corday crept ever closer to him. As he busily wrote out the list, Marat said, “Their heads will fall within a fortnight.”

Now within striking distance, Corday pulled the knife from her corset and plunged it deep into his chest, just under his right clavicle, opening the brachiocephalic artery, close to the heart. Marat, still clutching the list of names, slumped into the tub as he called out his last words: “Aidez-moi, ma chère amie!” (“Help me, my dear friend!”). The wound was fatal. In response to Marat’s cries, his wife Simonne Evrard, and two others rushed into the room and seized Corday. Two neighbors, a military surgeon and a dentist, attempted to revive Marat to no avail. Officials arrived to interrogate Corday and to calm a hysterical crowd who appeared ready to lynch her.

Corday’s manifesto claimed: “I have avenged many innocent victims, I have prevented many other disasters. The people, one day disillusioned, will rejoice in being delivered from a tyrant…I rejoice in my fate, the cause is good…I alone conceived the plan and executed it. Crime is shame, not the scaffold!” Corday credited her single-blow knifing of Marat not to skill or practice but to luck. Arrested on the spot, she was tried and convicted by the Revolutionary Tribunal and sentenced to death by guillotine on the Place de la Révolution. On July 17, 1793, four days after Marat was killed, Corday was led to the guillotine via the tumbril, an open cart used to transport its load of condemned prisoners to the guillotine amid the shouts and jeers of bystanders. Corday stood calmly facing the crowd, suddenly, the heavens opened the thousands of curious on-lookers were drenched by a sudden summer rainfall. Corday never flinched.

Corday strode confidently to the guillotine, curtseyed to the crowd, leaned against the Bascule, and was lowered face down horizontally, her head placed into the Lunette. The Declic (handle) was pulled by the hooded executioner, releasing the heavy Mouton (weight) and blade from the crossbar. A silent swish swept the crowd as Corday’s head tumbled into the basket below. The Bascule, a sort of table, was hinged to make it easier to push the headless body into a larger side basket immediately after the execution. Moments after Corday’s decapitation, a carpenter named Legros leaped from the crowd and lifted her head from the basket. He turned towards the crowd and slapped it on the cheek. Horrified witnesses reported an expression of “unequivocal indignation” on her face when her cheek was slapped and that “Charlotte Corday’s severed head blushed under the executioner’s slap.” Ever since, the incident has fueled the suggestion that victims of the guillotine retain consciousness for a short while after decapitation. For that offense, Legros the carpenter was imprisoned for three months. To make matters worse, believing that there had to be a man sharing her bed who masterminded the assassination plan, officials had her body autopsied after her death to determine if she was a virgin. To their dismay, their non-scientific examination revealed that she was a virgin. Her body was buried in the Madeleine Cemetery, alongside the decapitated corpses of of King Louis XVI, Queen Marie Antoinette, and three thousand other guillotine victims. Legend claims that Corday’s skull was saved and passed from Parisian to Parisian (friend and foe alike) for generations after her execution.

Corday’s crime did not have the expected outcome and Marat’s assassination did not stop the reign of Terror. Instead, Marat became a martyr. Although the killing of Marat was considered vile, there is no doubt that the murder changed the political role and position of women during the French Revolution. Corday’s action aided in restructuring the private versus public role of women in society at the time. The idea of women as second-class citizens was challenged, and Corday was considered a hero. As the revolution progressed, the Girondins became progressively more opposed to the radical, violent views of the Montagnards espoused by Marat, Robespierre, and others.

However, Corday’s critics quickly elevated Marat to the level of the immortals. His heart was embalmed separately and placed in an urn on an altar erected to his memory. His remains were transferred to the Panthéon where his near messianic role in the Revolution was gaslighted in a eulogy delivered by the Marquis de Sade, who compared Marat to Jesus Christ and idealized him as a man who loved only the people of France. Marat was transformed into a quasi-saint, his bust often replacing crucifixes in the churches of Paris. After the ousting of Maximilien Robespierre a year later, Marat’s reputation plummeted. His busts were knocked off their pedestals, carried away, and dragged through the streets by local children to the chants of ‘Marat, voilà ton Panthéon!’ (Marat, here is your Panthéon) before being dumped into the sewers. The few remaining statues of Marat were melted down during the Nazi occupation of Paris in World War II. Strangely, he continued to be held in high regard in the Soviet Union with many citizens, streets, and even a battleship sharing the name Marat.

Europeans remain split on the legacy of Corday. Some place her alongside Joan of Arc, the patron saint of France, who died 350 years prior, and others dismiss her as an idealistic radical. Corday lives on in popular memory through numerous works of art, poetry, plays, and literature including works by Percy Bysshe Shelley and Oscar Wilde, and her story is referenced variously in Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm and Les Misérables. Marat’s wife peddled his bathtub to the highest bidder but not very successfully. Reportedly, interested parties included Madame Tussaud’s wax museum and P.T. Barnum, but it ultimately landed in the Musée Grévin, a Paris wax museum, where it remains today. The tub is in the shape of an old-fashioned high-buttoned shoe with a copper lining. However, the most tangible reminder of Marat’s death is Jacques-Louis David’s painting. David was not only the painter but also the man who organized Marat’s funeral. Marat’s disorder accelerated decomposition, making any realistic depiction of the scene impossible. The result was that David’s work beautified the skin that in reality had been discolored and scabbed from his chronic skin disease. The resulting painting was widely criticized as glorifying Marat’s death.

As for Corday’s reputation, history recalls her as the “Angel of Assassination” and lauds her as an early pioneer in the annals of women’s rights. After the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, the April 29, 1865, Harper’s Weekly mentioned Corday in a series of articles analyzing the assassination as the “one assassin whom history mentions with toleration and even applause”, but goes on to conclude that her assassination of Marat was a mistake in that she became Marat’s last victim rather than vindicating his thousands of victims. Proving that violence in the interest of “small d” democracy is, was, and always will be, futile and unacceptable.

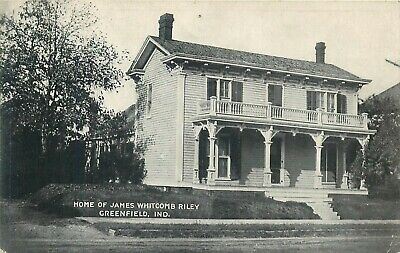

Although Lincoln and Riley died a half-century apart, the men had much in common. The two were considered the state’s most famous Hoosiers (that is until John Dillinger died in 1934) and their names were often linked in speeches, newspaper articles, books and periodicals in the first fifty years of the 20th century. One of my favorite quotes found while searching the virtual stacks of old newspapers comes from the July 20, 1941 Manhattan Kansas Morning Chronicle: “If you want to succeed in life, you might run a better chance if you live in a house with green shutters. Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain and James Whitcomb Riley all lived in such houses.” Lincoln and Riley epitomized everything that was good about being a Hoosier, right down to the color of their green window shutters.

Although Lincoln and Riley died a half-century apart, the men had much in common. The two were considered the state’s most famous Hoosiers (that is until John Dillinger died in 1934) and their names were often linked in speeches, newspaper articles, books and periodicals in the first fifty years of the 20th century. One of my favorite quotes found while searching the virtual stacks of old newspapers comes from the July 20, 1941 Manhattan Kansas Morning Chronicle: “If you want to succeed in life, you might run a better chance if you live in a house with green shutters. Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain and James Whitcomb Riley all lived in such houses.” Lincoln and Riley epitomized everything that was good about being a Hoosier, right down to the color of their green window shutters.

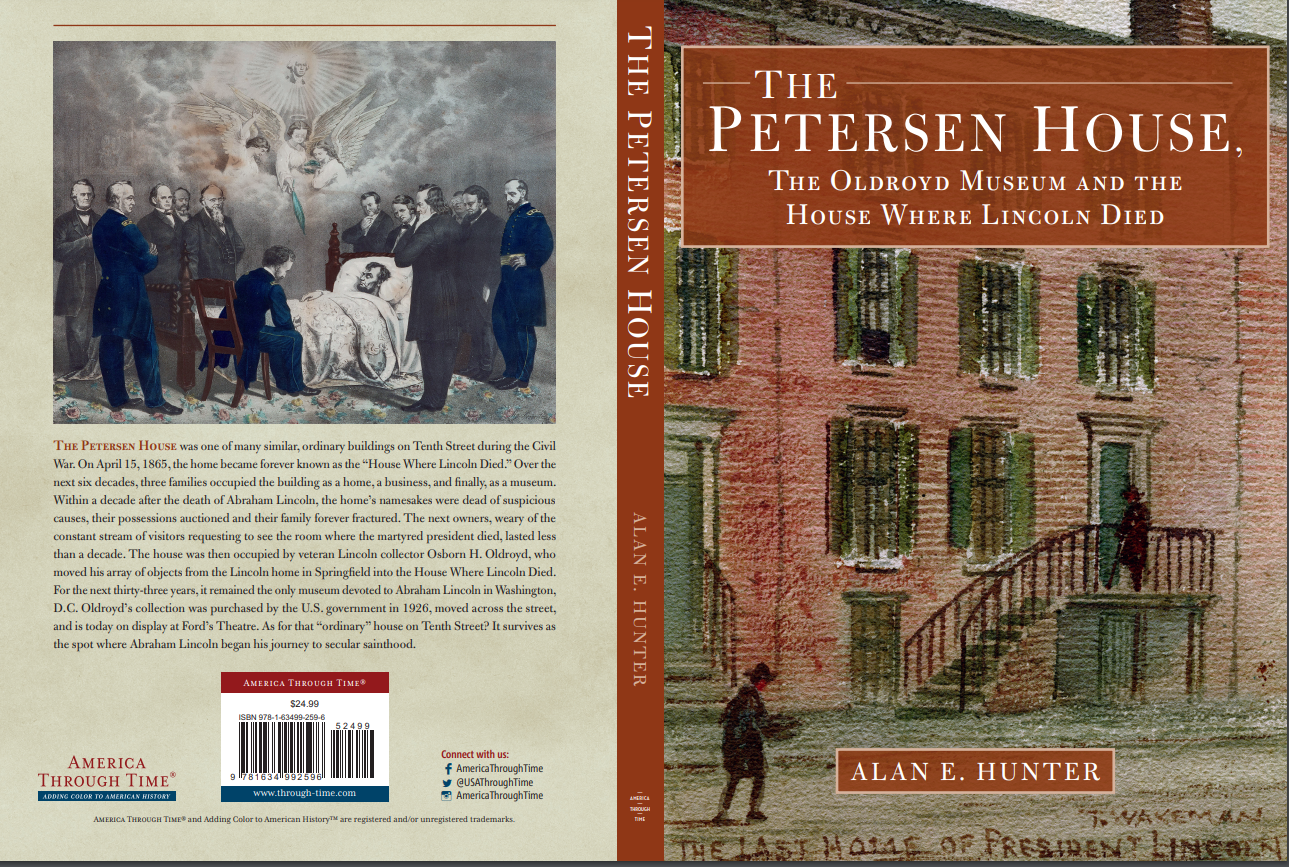

Oldroyd, a thrice-wounded Civil War veteran, collector, curator and author, is perhaps the father of the house museum in America. One of Oldroyd’s books, a compilation of poems entitled, “The Poets’ Lincoln— Tributes In Verse To The Martyred President”, was published in 1915. James Whitcomb Riley’s poem, A Peaceful Life with the name “Lincoln” in parenthesis as a sub-title can be found there on page 31. In Oldroyd’s version, the first line differs from Riley’s original version. Riley’s handwritten original (found today in the archives of the Lilly Library on the Bloomington campus of Indiana University) begins: “Peaceful Life:-toil, duty, rest-“. Oldroyd’s book version begins; “A peaceful life —just toil and rest—.” Interestingly, the Oldroyd version has become the standard. And there you have it. Oldroyd’s influence is subtle, his name largely unknown, yet he stays with us to this day.

Oldroyd, a thrice-wounded Civil War veteran, collector, curator and author, is perhaps the father of the house museum in America. One of Oldroyd’s books, a compilation of poems entitled, “The Poets’ Lincoln— Tributes In Verse To The Martyred President”, was published in 1915. James Whitcomb Riley’s poem, A Peaceful Life with the name “Lincoln” in parenthesis as a sub-title can be found there on page 31. In Oldroyd’s version, the first line differs from Riley’s original version. Riley’s handwritten original (found today in the archives of the Lilly Library on the Bloomington campus of Indiana University) begins: “Peaceful Life:-toil, duty, rest-“. Oldroyd’s book version begins; “A peaceful life —just toil and rest—.” Interestingly, the Oldroyd version has become the standard. And there you have it. Oldroyd’s influence is subtle, his name largely unknown, yet he stays with us to this day.

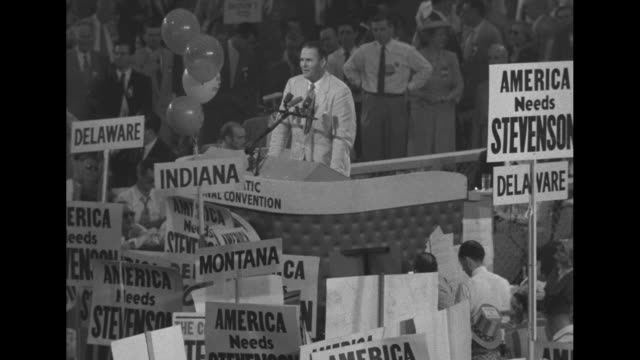

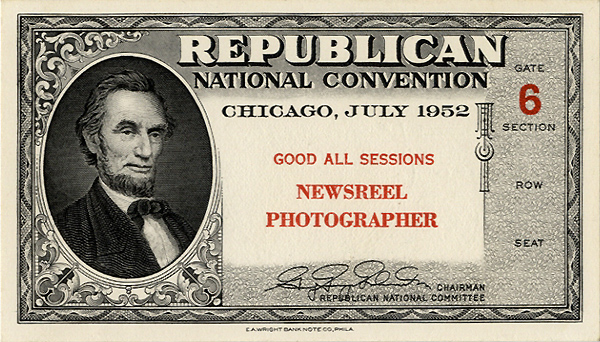

The letter continues, ” Gov. Battle has a brother living in Charleston, who goes to our church, + Tom knows him quite well, + we have been in their home, so we were especially interested in what he had to say. We thought the Louisiana Governor was crying, – did you? But I’m a telling you, the more I see of the southern states vs. the northern states, the prouder I am of being a Southerner!” Virginia Governor John Battle, of whom the letter speaks, was a Delegate to the DNC in 1952. When the Virginia delegation was threatened with expulsion at the convention for refusing to sign a loyalty oath (to whomever the party nominated), Battle delivered a speech to the convention preventing their expulsion.

The letter continues, ” Gov. Battle has a brother living in Charleston, who goes to our church, + Tom knows him quite well, + we have been in their home, so we were especially interested in what he had to say. We thought the Louisiana Governor was crying, – did you? But I’m a telling you, the more I see of the southern states vs. the northern states, the prouder I am of being a Southerner!” Virginia Governor John Battle, of whom the letter speaks, was a Delegate to the DNC in 1952. When the Virginia delegation was threatened with expulsion at the convention for refusing to sign a loyalty oath (to whomever the party nominated), Battle delivered a speech to the convention preventing their expulsion.