Here is the radio show companion to my March 13th & 20th and June 19, 2025 articles in the Weekly View newspaper, all of which are available to read on this site.

Here is the radio show companion to my March 13th & 20th and June 19, 2025 articles in the Weekly View newspaper, all of which are available to read on this site.

Original publish date May 15, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/05/15/foul-ball/

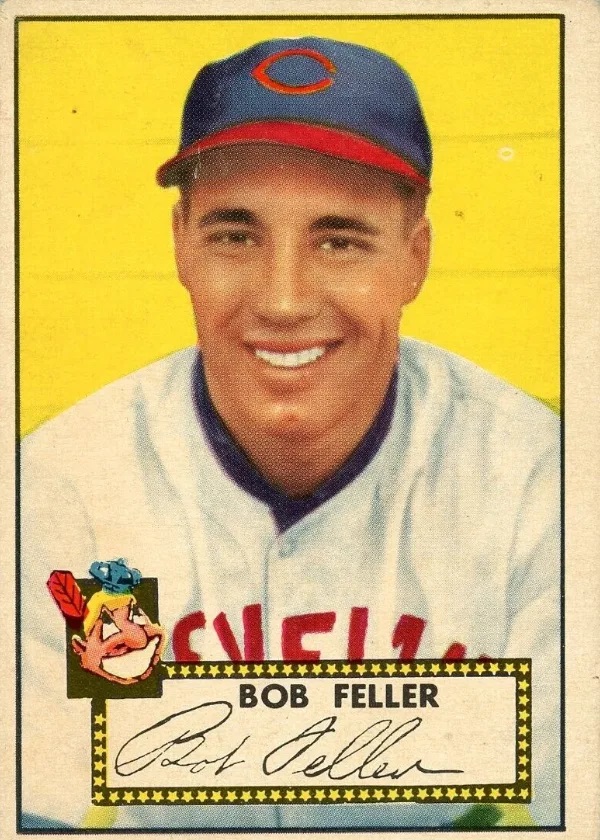

Last week, I ran a story about Cleveland Indians phenom Bob Feller’s pitched foul ball that hit and injured his mother during a game against the White Sox at old Comiskey Park in Chicago. That got me thinking about other foul ball stories and legends I’d heard about. Growing up, I spent a lot of time at old Bush Stadium on 16th Street in Indy. My dad, Robert Eugene Hunter, a 1954 Arsenal Tech grad, had worked there as a kid selling Cracker Jack/popcorn in the stands during the Victory Field years. He recalled with pleasure seeing Babe Ruth in person there and could name his favorites from those great Pittsburgh Pirates farm club teams from the late 1940s/early 1950s. I can’t tell you how many RCA Nights at Bush Stadium he took me to back in the 1970s during the team’s affiliation with the Cincinnati Reds Big Red Machine. During those outings, nothing was more exciting than chasing foul balls.

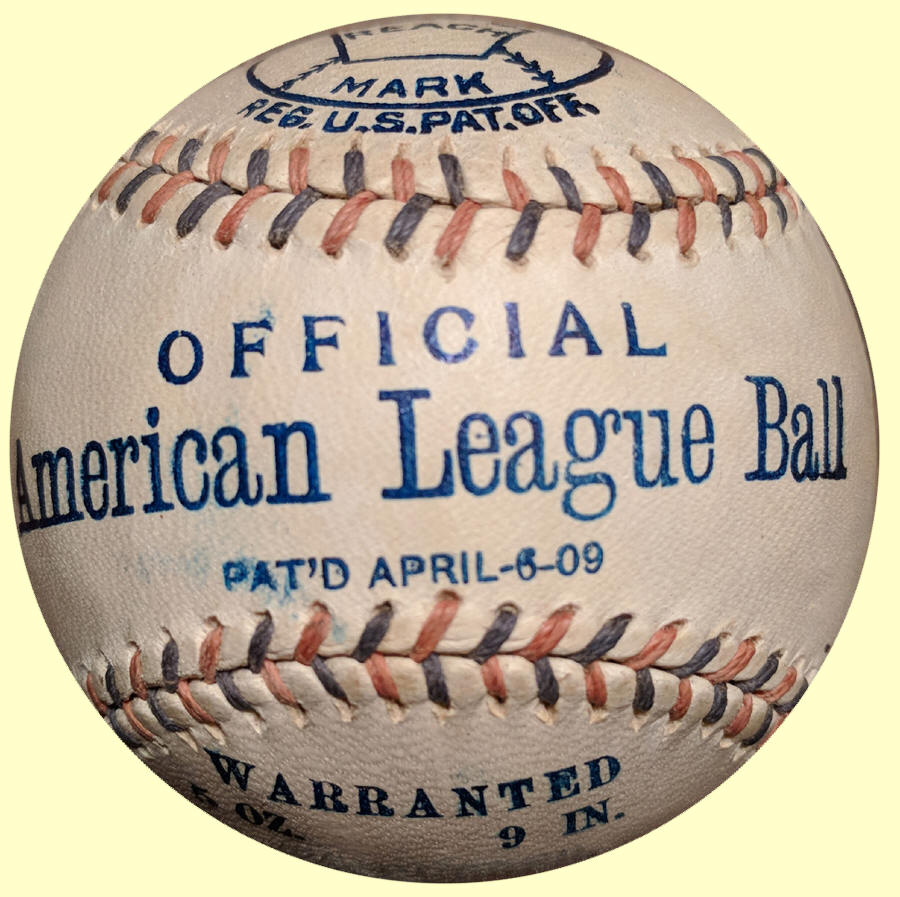

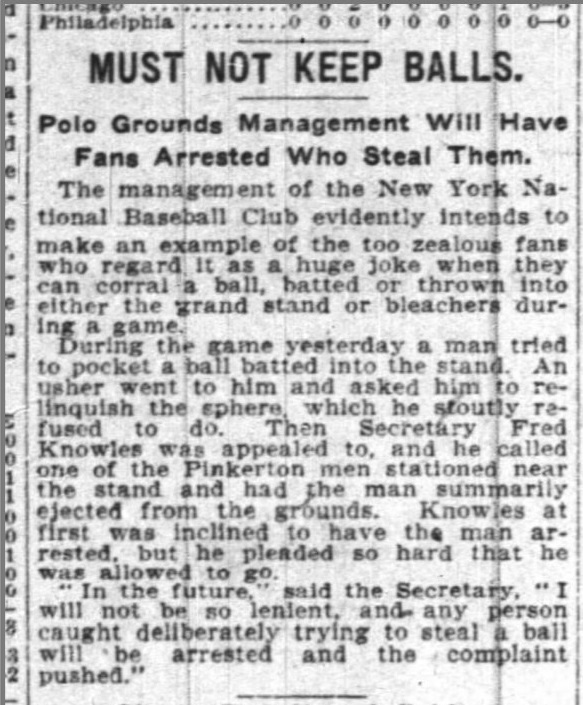

Not all foul balls are fun adventures, though; some are crazy, and others are just plain scary. Growing up, I loved reading about the exploits of those players who played before World War I. Back in those days, baseballs were considered team property and quite expensive. Fans were expected to return any ball hit into the stands (including homeruns), and balls hit out of the stadium were meticulously retrieved. In 1901, the National League rules committee, as a way of cutting costs, suggested fining batters for excessively fouling off pitches. Beginning in 1904, per a newly created league rule, teams posted employees in the stands whose sole job was to retrieve foul balls caught by the fans. Fans had a keen sense of humor, though, and they would often hide them from the “goons” or frustrate the hapless employees by throwing them from row to row. Sometimes, the games of keep-away in the stands were more fun to watch than the ones on the field. But those early WWI stories mostly involved the exploits of the players, not the fans. There were some characters in the league back then. Some of them are long forgotten and some made the Baseball Hall of Fame.

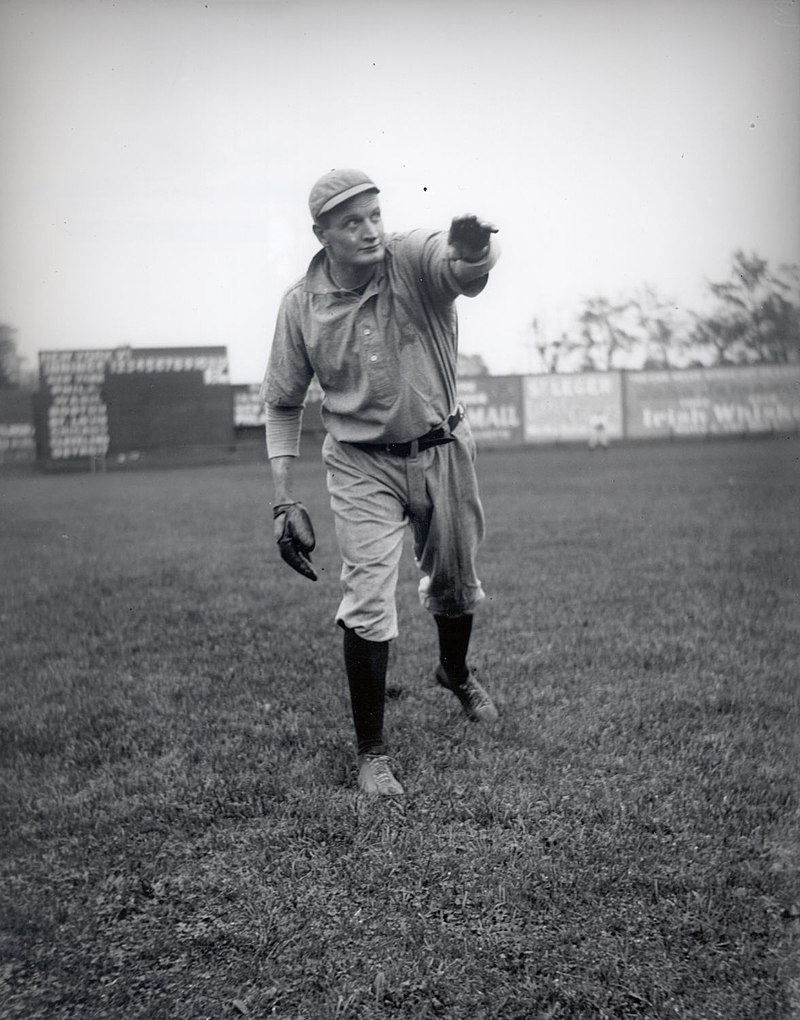

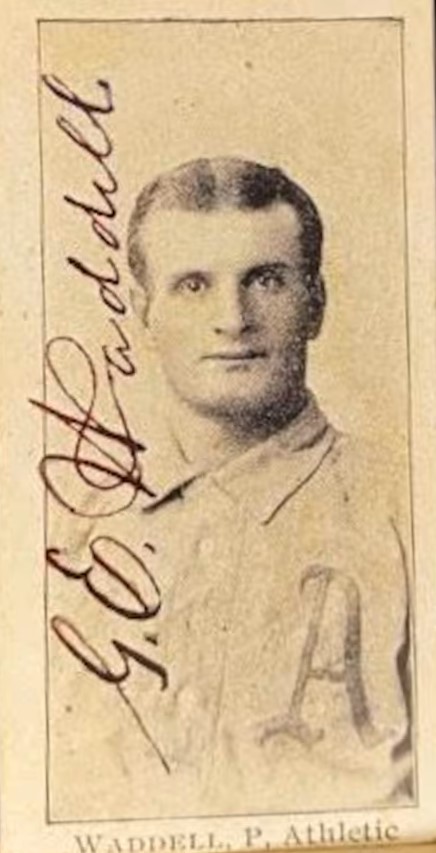

One of my favorite players from that hardball era was a square-jawed eccentric left-handed pitcher from the oil town of Bradford, Pa. named George Edward “Rube” Waddell (1876-1914). Rube played for 5 teams in 13 years. His lifetime 193-143 record, 2,316 strikeouts, and 2.16 ERA landed him in the Hall of Fame. And if there were a hall of fame for flakes in baseball, Rube would have been a first-ballot electee. If a plane flew above the field, Rube would stop in the middle of a game. If Rube heard the siren of a firetruck, he’d drop his glove and chase it. He once left in the middle of a game to go fishing. Opposing fans knew that Rube was easily distracted so they brought puppies to the game and held them up in the stands to throw him off. Rival teams brought puppies into the dugout for the same reason, knowing that Rube would drop his glove and run over to play with them every time. Shiny objects seemed to put Rube in a trance. His eccentric behavior led to constant battles with his managers and scuffles with bad-tempered teammates. Even though he was a standout pitcher, Rube’s foulball stories came off his bat, not out of his hand.

On August 11, 1903, the Philadelphia Athletics were visiting the Red Sox. In the seventh inning, Rube Waddell was at the plate. Waddell lifted a foul ball over the right field bleachers that landed on the roof of a Boston baked bean cannery next door. The ball rolled to a stop and became wedged in the factory’s steam whistle, which caused it to go off. It wasn’t quitting time yet, but the workers abandoned their posts, thinking it was an emergency. The employee exodus caused a giant caldron full of beans to boil over and explode. Suddenly, the ballpark was showered by scalding hot beans. Nine days before, on August 2, another foul ball off the bat of Waddell hit a spectator, supposedly igniting a box of matches in the fan’s pocket and ultimately setting the poor guy’s suit on fire and causing an uproar.

Waddell’s 1903 E107 Card.

Still, a foul ball hit by the aptly named George Burns of the Tigers in 1915 is worth mentioning in the same breath. His “scorching” foul liner struck an unlucky fan in the area of his chest pocket, where he was carrying a box of matches. The ball ignited the matches, and a soda vendor had to come to the rescue, dousing the flaming fan with bubbly to put out the fire.

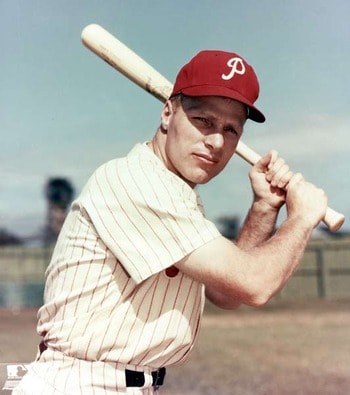

Richie Ashburn figures in many of the best foul ball stories in baseball lore. A contact hitter, Ashburn had the ability to foul off many consecutive pitches till he found one he liked. On one occasion, he fouled off fourteen consecutive pitches against Corky Valentine of the Reds. Another time, he victimized Sal “The Barber” Maglie for “18 or 19″ fouls in one at-bat. ”After a while,” said Ashburn, “he just started laughing. That was the only time I ever saw Maglie laugh on a baseball field.” Ashburn’s bat control was such that one day he asked teammates to pinpoint a particularly offensive heckler seated five or six rows back. The next time up, Ashburn nailed the fan in the chest. On another occasion, Ashburn unintentionally injured a female fan who was the wife of a Philadelphia newspaper sports editor. Play stopped as she was given medical aid. Action resumed as the stretcher wheeled her down the main concourse, and, unbelievably, Ashburn’s next foul hit her again. Thankfully, she escaped with minor injuries.

Another notable foul ball hitter was Luke Appling, the Hall of Fame shortstop with a career batting average of .310. As the story goes, Appling once asked White Sox management for a couple of dozen baseballs, so he could autograph them and donate them to charity. Management balked, citing a cost of several dollars per baseball. Appling bought the balls from his team, then went out that day and fouled off a couple dozen balls, after which he tipped his hat toward the owner’s box. He never had to pay for charity balls again, the legend goes.

Another great foul ball story involves Pepper Martin and Joe Medwick of the St. Louis Cardinals famous Gas House Gang teams of the mid-1930s. With Martin at bat, Medwick took off from first base, intending to take third on the hit-and-run. Martin fouled the ball into the stands, and Reds catcher Gilly Campbell reflexively reached back to home plate umpire Ziggy Sears for a new ball. Then, just for fun, Campbell launched the ball down to third, where Sears, forgetting that a foul had just been hit and that he had given Campbell a new ball, called Medwick out. The Cardinals were furious, but not wanting to admit his error, Sears refused to reverse his call, and Medwick was thrown out-on a foul ball!

The great Cal Ripken Jr. made life imitate art with a foul ball in 1998. In the movie The Natural, Roy Hobbs lofts a foul ball at sportswriter Max Mercy, as Mercy sits in the stands drawing a critical cartoon of the slumping Hobbs. Baltimore Sun columnist Ken Rosenthal faced a similar wrath of the baseball gods after he wrote a column in 1998 suggesting that it might be time for Ripken to voluntarily end his streak, at that point several hundred games beyond Lou Gehrig’s old record, for the good of the team. Ripken responded by hitting a foul ball into the press box, which smashed Rosenthal’s laptop computer, ending its career. When told of his foul ball’s trajectory, Ripken responded with one word: “Sweet.”

Another sweet story involves a father and son combination. In 1999, Bill Donovan was watching his son Todd play center field for the Idaho Falls Braves of the Pioneer League. Todd made a nice diving catch and threw the ball back into the second baseman, who returned it to the pitcher. On the next pitch, a foul ball sailed into the outstretched hands of the elder Donovan. “I was like a kid when I caught it,” said the proud papa. “It made me wonder when was the last time that a father and son caught the same ball on consecutive pitches.”

One day in 1921, New York Giants fan Reuben Berman had the good fortune to catch a foul ball, or so he thought. When the ushers arrived moments later to retrieve the ball, Reuben refused to give it up, instead tossing it several rows back to another group of fans. The angered usher removed Berman from his seat, took him to the Giants’ offices, and verbally chastised him before depositing him in the street outside the Polo Grounds. An angry and humiliated Berman sued the Giants for mental and physical distress and won, leading the Giants, and eventually other teams, to change their policy of demanding foul balls be returned. The decision has come to be known as “Reuben’s Rule.”

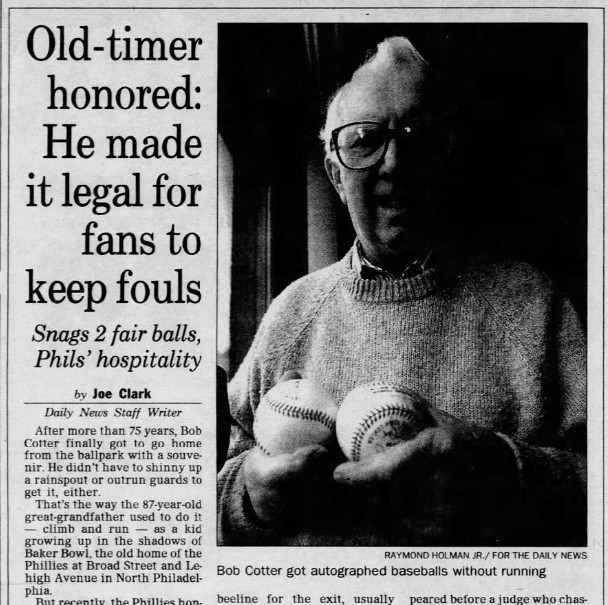

While Berman’s case was influential, the influence had not spread as far as Philadelphia by 1922, when 11-year-old fan Robert Cotter was nabbed by security guards after refusing to return a foul ball at a Phillies game. The guards turned him over to police, who put the little tyke in jail overnight. When he faced a judge the next day, young Cotter was granted his freedom, the judge ruling, “Such an act on the part of a boy is merely proof that he is following his most natural impulses. It is a thing I would do myself.” The tide eventually changed for good, and the practice of fans keeping foul balls became entrenched. World War II was another time when patriotic fans and owners worked together to funnel the fouls off to servicemen. A ball in the Hall of Fame’s collection is even stamped “From a Polo Grounds Baseball Fan,” one of the more than 80,000 pieces of baseball equipment donated to the war effort by baseball by June 1942.

One of those baseballs may well have been involved in one of the strangest of all foul ball stories. In a military communique datelined “somewhere in the South Pacific,” the story is told of a foul ball hit by Marine Private First Class George Benson Jr., which eventually traveled 15 miles. Benson’s batting practice foul looped up about 40 feet in the air, where it smashed through the windshield of a landing plane. The ball hit the pilot in the face, fracturing his jaw and knocking him unconscious. A passenger, Marine Corporal Robert J. Holm, muttering a prayer, pulled back on the throttle and prevented the plane from crashing, though he had never flown before. The pilot recovered momentarily and brought the plane to a landing at the next airstrip, 15 miles away.

In 1996, at the age of 71, former President Jimmy Carter made a barehanded catch of a foul ball hit by San Diego’s Ken Caminiti, while attending a Braves game. “He showed good hands,” said Braves catcher Javy Lopez.

With foul balls by this time an undeniable right for fans at the ballpark, what are your actual chances of catching a foul ball at a game? Well, to start with, the average baseball is in play for six pitches these days, which makes it sound as though there will be many chances to catch a foul ball in each game. While comprehensive statistics are not available, various newspapers have sponsored studies which, uncannily, seem quite often to come down to 22 or 23 fouls into the stands per game.

That seems like a healthy number until you look at average major league attendance at games. In the year 2000, the average game was attended by 29,938 fans. With 23 fouls per game, that works out to a 1 in 1,302 chance of catching a foul ball. With numbers like that, no wonder it feels so special to catch a foul ball. Nevertheless, those who yearn to catch a foul ball can improve their chances. I have listed some tips to help you bring home that elusive foul ball. Good luck!

Original Publish Date March 6, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/03/06/osborn-h-oldroyds-greatest-fear/

My wife and I recently traveled to Springfield, Illinois for a book release event (actually two books). One book on Springfield’s greatest living Lincoln historian, Dr. Wayne C. “Doc” Temple, and the other on my muse for the past fifteen years, Osborn H. Oldroyd. I have fairly worn out my family, friends, and readers with the exploits of Oldroyd over the years. He has been the subject of two of my books and a bevy of my articles. Oldroyd was the first great Lincoln collector. He exhibited his collection in Lincoln’s Springfield home and then in the House Where Lincoln Died in Washington DC from 1883 to 1926. Oldroyd’s collection survives and forms much of the objects in Ford’s Theatre today.

For this trip, we traveled up from the south to Springfield through parts of northwest Kentucky and southeast Missouri. What struck us most were the conditions of the small towns we drove through. Today many of these little burgs and boroughs are in sad shape, littered by once majestic brick buildings featuring the names of the merchants that built them above the doorways, eaves, and peaks of their frontispieces in a valiant last stand. Most had boarded-up windows and doors and some with ghost signs of products and services that disappeared generations ago.

They are tightly packed and many share common walls. We were amazed how many of them have caved-in or worse, burnt down. The caved-in buildings are the work of Father Time and Mother Nature, but the burnt ones look as if the fires were extinguished just recently. My wife deduces that these are likely the result of the many meth labs that blight these long-forgotten, empty buildings. Indeed, a little research reveals that these rural areas do lead the league in these hastily constructed, outlaw drug factories.

Of course, that got me thinking about Oldroyd’s museum. Oldroyd lobbied for decades to have his collection purchased by the U.S. government and preserved for future generations to explore. The Feds eventually purchased it in 1926 for $50,000 (around $900,000 today). For over half a century while assembling his collection, Oldroyd had one great fear: Fire. Visiting the House Where Lincoln Died today, the building remains unique in size and architecture compared to those around it. In Oldroyd’s day, smoking cigars, pipes, and cigarettes indoors was as prevalent as carrying cell phones and water bottles are today. The threat of fire was very real for Oldroyd.

The March 20, 1903, Huntington Indiana Weekly Herald ran an article titled “A Visit to the Lincoln Museum in Washington City.” After describing the relics in the collection, columnist H.S. Butler states, “It is hoped the next Congress will purchase this collection and care for it. Mr. Oldroyd is not a man of means such as would enable him to do all he would like, and it seems to me a little short of criminal to expose such valuable relics, impossible to replace, to the great risk of fire. I understand Congressman [Charles] Landis, of Indiana, is trying to get the collection stored in the new Congressional Library, in itself the handsomest structure, interiorly, in Washington. I hope that his brother, the congressman from the Eleventh District [Frederick Landis], will lend his influence to Senators [Charles] Fairbanks and [Albert] Beveridge to urge forward the same end.”

Fifteen years later, the Topeka State Journal described an event that fueled Oldroyd’s concern. “May 21 [1918]-a few days ago the Negro cook in the kitchen of a dairy lunch spilled some fat on the fire and the resulting blaze was extinguished with some difficulty. The unique feature of this trifling accident was that, had the blaze gotten beyond control, it would probably have destroyed a neighboring house in which is the greatest collection in the world of relics, manuscripts, and books bearing upon the life and death of Abraham Lincoln…Sixty feet away from the room in which Lincoln died are three kitchens of restaurants and a hotel. More than one recent fire scare has caused alarm over the danger that threatens these relics.”

The February 11, 1922, Dearborn [Michigan] Independent reported, “A vagrant spark, a carelessly tossed cigarette or cigar stub, an exposed electric wire might at any time mean the destruction of the collection and the building which, of course, is itself a sacred bit of Lincolniana.” The January 21, 1924, Daily Advocate of Belleville, Ill. reported “The collection is contained in a small and overcrowded room of the house opposite Ford’s Theatre, with two restaurants across a narrow alleyway constituting a constant fire menace…it is likely that the U.S. Government will request that the Illinois Historical Society return the bed in which Lincoln died, that it may again be placed in the room it occupied on that fateful night and the entire setting restored.” Due to that unresolved fire threat the bed was never returned and is today on display at the Chicago History Museum. A 1924 Christmas day article in the Washington Standard 1924 described, “There are a number of restaurants in the block at the rear, and once an oil supply house did business close at hand. On two occasions there have been fires in the neighborhood.”

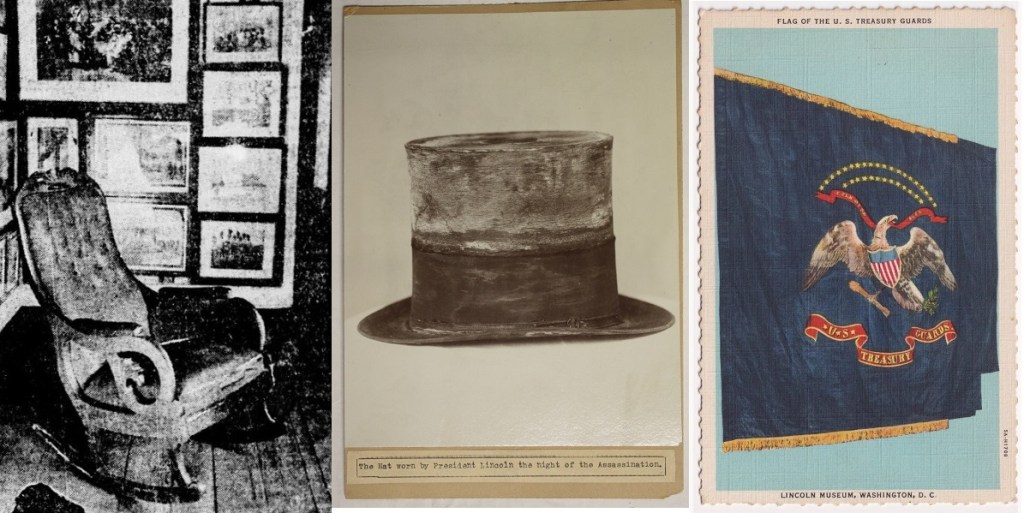

The July 6, 1926, Indianapolis News speculated, “The government will add to the collection the high silk hat Lincoln wore to the theatre that fatal night, the chair in which he sat in the presidential box, and the flag in which Booth’s foot caught. The flag now hangs in the treasury, while the hat and chair are in storage. These articles formerly were in the Oldroyd collection, but after a fire in the neighborhood some years ago, officials of the government took them back, fearing that they might be destroyed.” The February 18, 1927, Greenfield [Indiana] Reporter stated, “The plan proposed by Senator Watson, of Indiana, and Rep. Rathbone of Illinois, is to remodel the building to protect it against the danger of fire and the ravages of age. They would…place in it the famous Oldroyd collection of Lincoln relics.” Fire remained a nightmare for Oldroyd right up to the day he died on October 8, 1930.

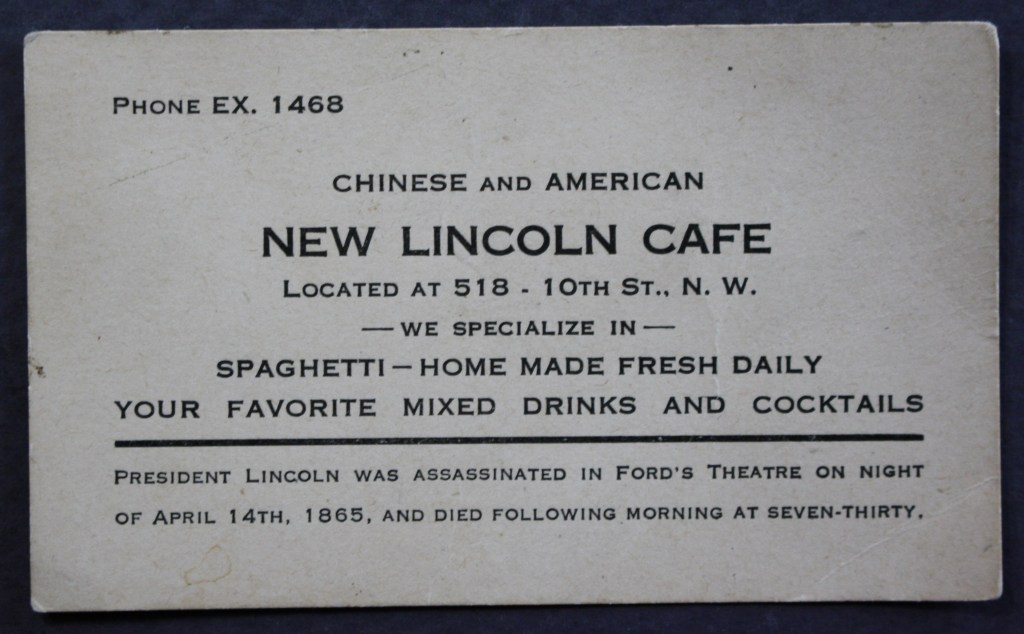

Ironically, after that book signing I found myself browsing the bookstore. I found there a 2 1/2” x 4” business card from the New Lincoln Cafe in the adjoining building to the north of Oldroyd’s Museum (at 516 10th St. NW). Putting aside the fact that I have a personal affinity for old business cards, the item called out to me and made me wonder about the businesses that had been neighbors to this hallowed spot over the generations.

The card reads: “Chinese and American New Lincoln Cafe. Located at 518 10th St., N.W. Phone EX. 1468. We Specialize In Spaghetti-Home Made Fresh Daily. Your Favorite Mixed Drinks And Cocktails. President Lincoln Was Assassinated In Ford’s Theatre On Night Of April 14th, 1865, And Died Following Morning At Seven-Thirty.” A check of the records indicates that this restaurant remained next to the museum from the late 1930s to the early 1960s. This was just one of the businesses to call that space home over the generations.

Located in the Penn Quarter section of DC, the building was built sometime between 1865 to 1873. It envelopes the entire north side and part of the northwest back of the HWLD. It is 4 stories tall and features 11,904 square feet of retail space. One of the earliest storefronts to appear there was Dundore’s Employment Bureau which served D.C. during the 1870-90s. Ironically, when Dundore’s moved three blocks south to 717 M Street NW, the agency regularly advertised jobs at businesses occupying their old address for generations to come. Above the Dundore agency was Mrs. A. Whiting’s Millinery, which created specialty hats for women. The Washington Evening Star touted Mrs. Whiting’s “Millinery Steam Dyeing and Scouring” business for their “Imported Hats and Bonnets”. A 3rd-floor hand-painted sign on the bricks of the building advertising Whiting’s remained for years after the business vacated the premises, creating a “ghost sign” visible for many years as it slowly faded from view.

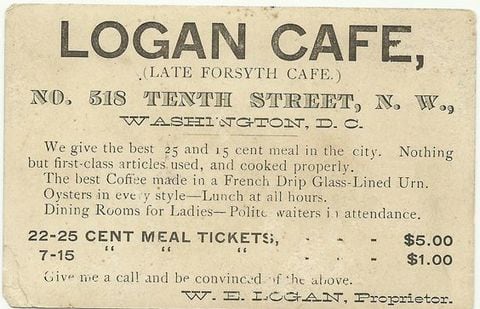

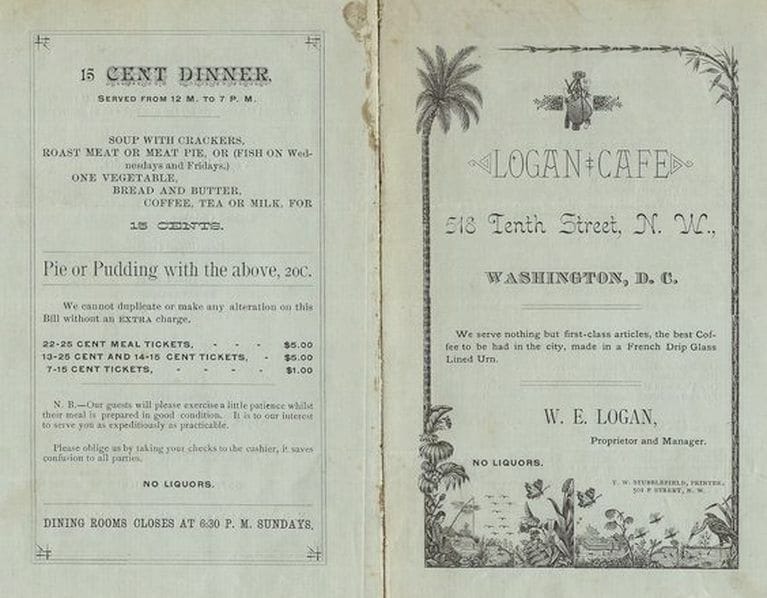

The Forsyth Cafe seems to have been the first bistro to pop up next to the Oldroyd Museum. In late February/March 1885 (in the leadup to Grover Cleveland’s first Presidential Inauguration), DC’s Critic and Record newspaper’s ad for the cafe decries, “Yes, One Dollar is cheap for the Inauguration supper, but what about those excellent meals at the Forsythe Cafe for 15 Cents?” The Forsyth continued to advertise their meals from 15 to 50 cents but by late 1886, they were gone, replaced by the Logan Cafe. The Logan offered 15 and 25-cent breakfasts, “Big” 10-cent lunches, and elaborate 4-course dinners of Roast beef, stuffed veal, lamb stew, & oysters. Proprietor W.E. Logan’s claim to fame was “the best coffee to be had in the city, made in French-drip Glass-Lined Urn” and “Special Dining Rooms for Ladies-Polite waiters in attendance” and his menus warned “No Liquors” served.

The June 4, 1887, Critic and Record reported on a “friendly scuffle” at the Logan between two “colored” employees when cook Charles Sail tripped waiter William Butler who hit his head on the edge of a table and died the next morning at Freedman’s Hospital. The men were described as best friends and the death was deemed an accident. By late 1887, the Logan disappears from the newspapers. From 1897 to 1897, the building was home to the Yale Laundry. The Jan. 7, 1897, DC Times Herald reported on an event that likely added to Oldroyd’s anxiety. The article, titled “Laundry is Looted” details a break-in next door to the museum during which a couple of safecrackers got away with $85 cash including an 1883 $5 gold piece.

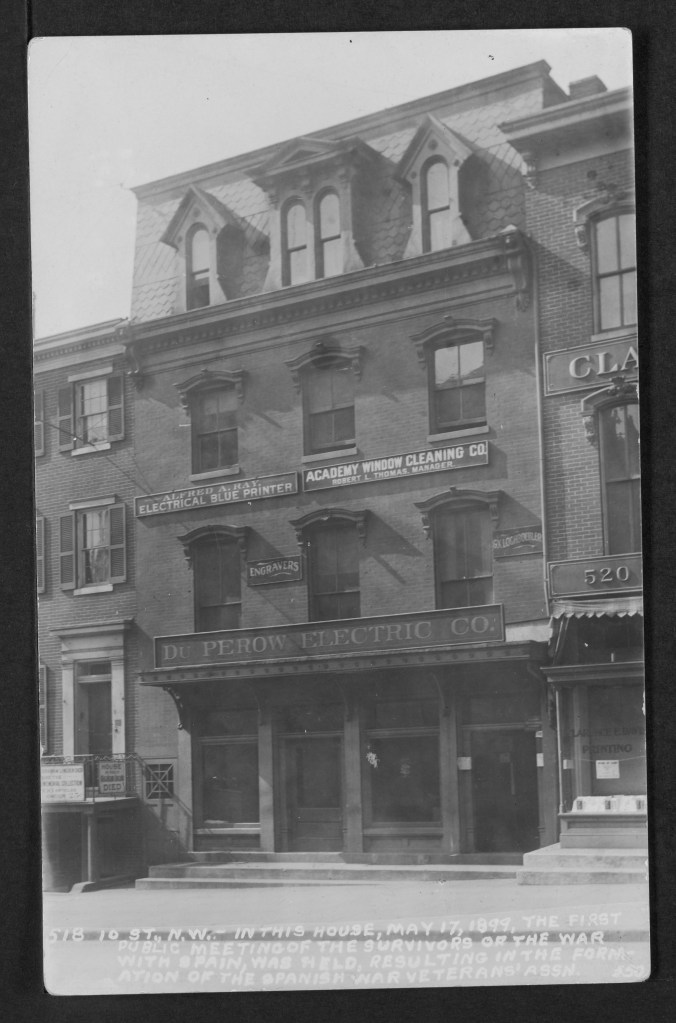

A real photo postcard in the collection of the District of Columbia Public Library pictures the building during Yale Laundry’s tenure captioned, “In this house the first public meeting of the survivors of the war with Spain, was held on May 17, 1899, resulting in the formation of the Spanish War Veterans’ Association.” The Dec. 1, 1900, Washington Star notes the addition of Harry Clemons Miller’s “Teacher of Piano” Studio and by 1903, the “Yale Steam Laundry” appeared in the DC newspapers at the address.

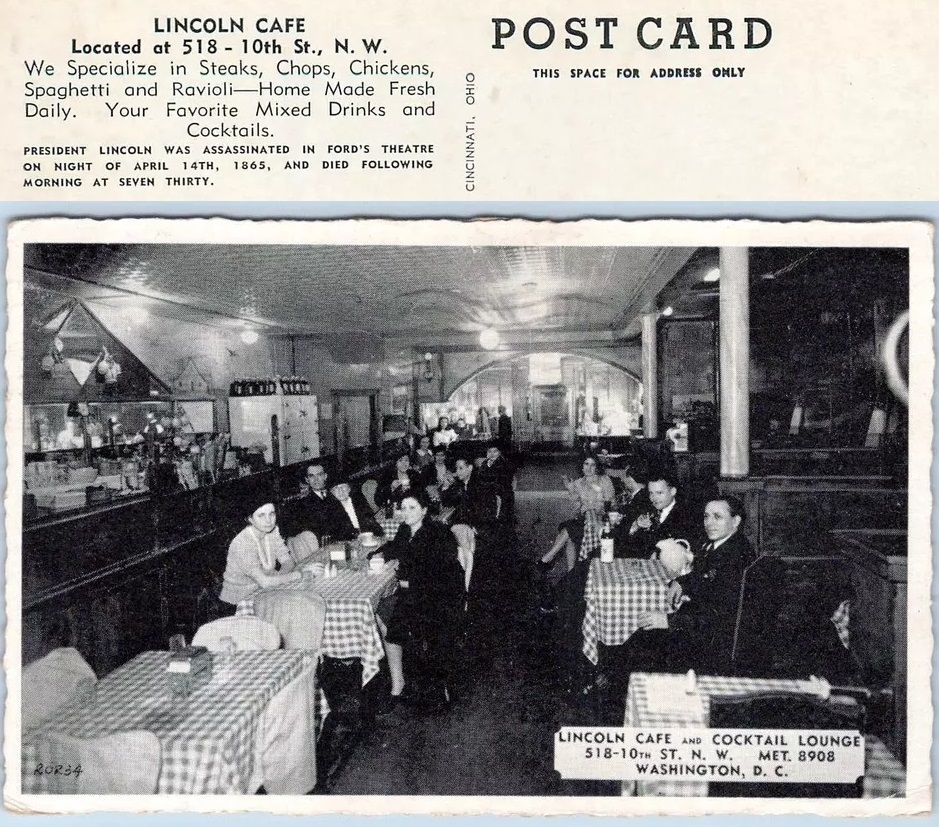

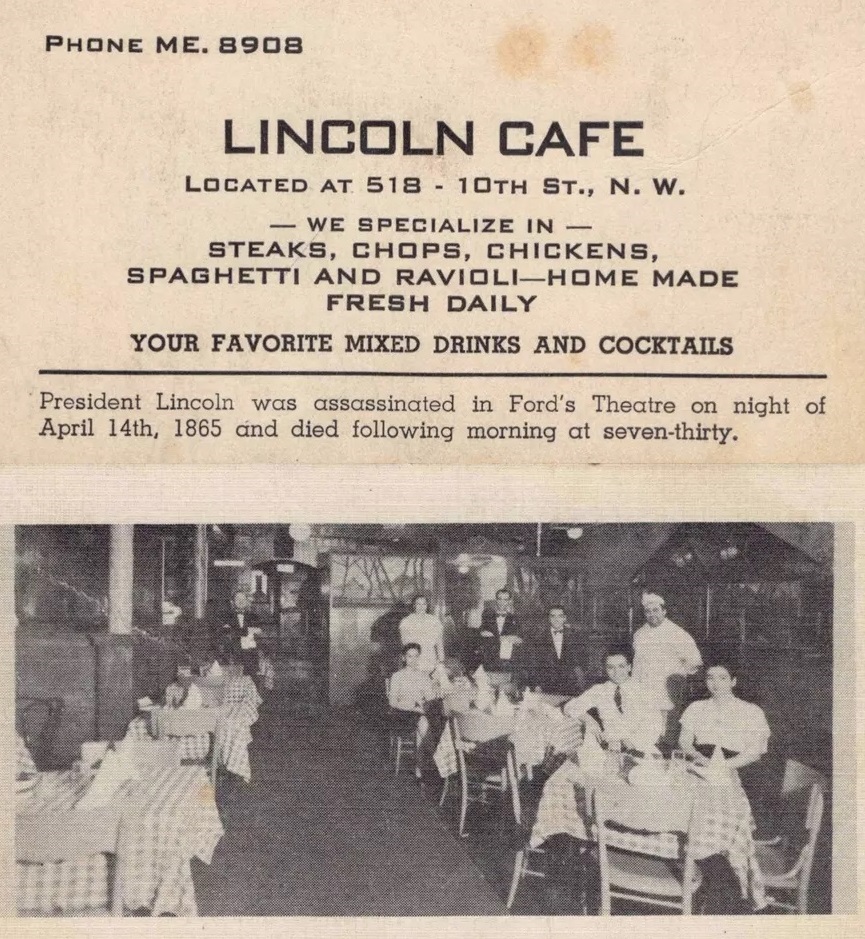

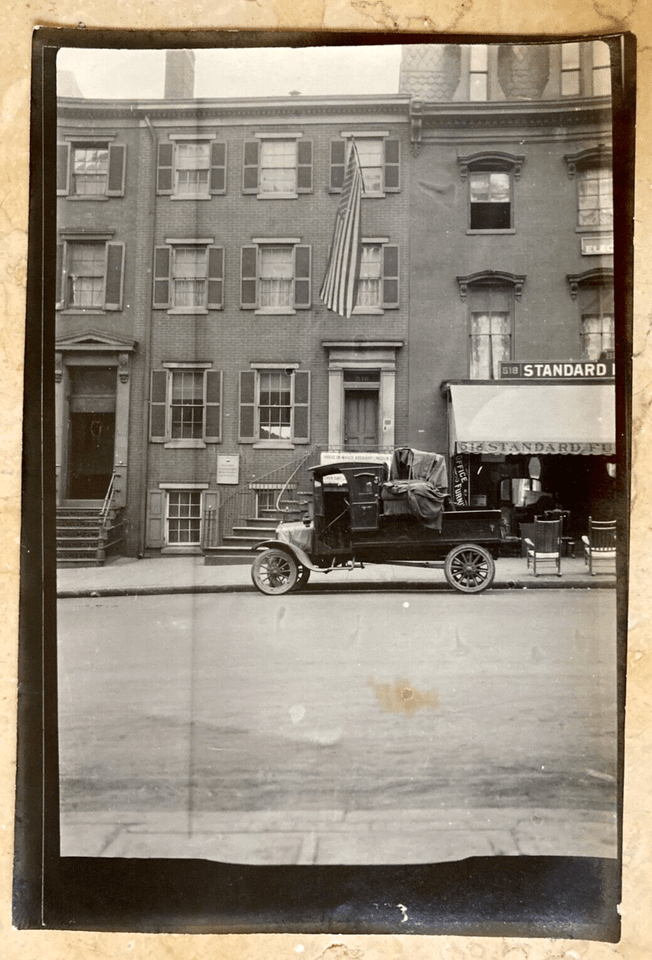

In 1909, Du Perow Electric Co. (AKA as “Du Pe”) and partner Alfred A. Ray “Electrical Blueprints” occupied the building. A window cleaning company occupied room # 9 and a leather goods store was located there during this same period. By 1912, the storefront was occupied by the Standard Furniture Co. At least one photo survives presenting an amusing scene of a furniture truck blocking the entrance to Oldroyd’s museum. Amusing to the viewer today but most assuredly not to the museum curator back in the day. Eventually, the restaurants, bars, and cafes that worried Oldroyd began to come and go, among them, the Lincoln Cafe & Cocktail Lounge, whose sign was dominated by the words “Beer Wine.” It appears that during the 1920-50s, a Pontiac, DeSoto, Plymouth Motor Car dealer known as “News & Company” kept an office in the building, with the car lot and gas station across the street.

Old-timers remember a long-term tenant known as “Abe Lincoln Candies” that occupied the space from the 1950-70s. Other recent tenants included Abe’s Cafe & Gift Shop, Bistro d’Oc and Wine Bar, Jemal’s 10th Street Bistro, Mike Baker’s 10th St Grill, and the I Love DC gift store, and last year, The Inauguration-Make America Great Again Store, who one Yelp reviewer complained was crowded with outdated, sketchy clothing and that “they make u give them a good review before they give u a refund kinda scummy.”

As for the building on the opposite side of Oldroyd’s museum at 514 Tenth St. NW, it remained a residence until 1922 when a $55,000, 10-story concrete & steel building with steam heat and a flat slag roof was built. Designed by architect Charles Gregg and built by Joseph Gant, the sky-scraper, known as the Lincoln Building, dwarfed the Oldroyd Museum. It was home to several businesses, including the Electrical Center (selling General Electric TVs, radios, and appliances) and the Garrison Toy & Novelty Co, its modern construction alleviated any concern of fire.

It must be noted that many great collections of Lincolniana fell victim to fire in the century and a half after Lincoln’s death. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 consumed many Lincoln objects, documents, and personal furniture that had been removed from the Springfield home after the President’s departure to Washington DC. On June 15, 1906, Major William Harrison Lambert (1842-1912), recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor and one of the Lincoln “Big Five” collectors, lost much of his collection in a fire at his West Johnson St. home in Germantown, Pa. Among the items lost were a bookcase, table, and chair from Lincoln’s Springfield law office and the chairs from Lincoln’s White House library. The threat of fire was a constant waking nightmare in Oldroyd’s life. While he did his best to control what went on inside his museum, he had no control over what happened outside. His life’s work of collecting precious Lincoln objects, over 3,500 at last count, could be gone in the flash of a pan.

ADDITIONAL IMAGES.

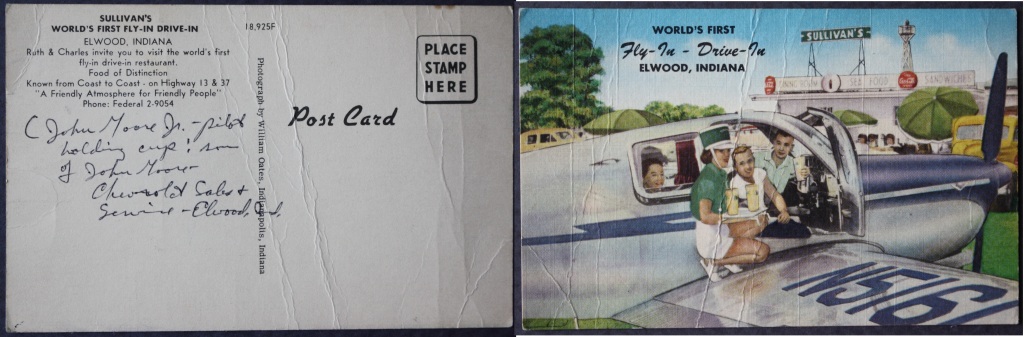

Original publish date March 24, 2022. https://weeklyview.net/2022/03/24/elwoods-airport-restaurant-the-worlds-only-fly-in-drive-in/

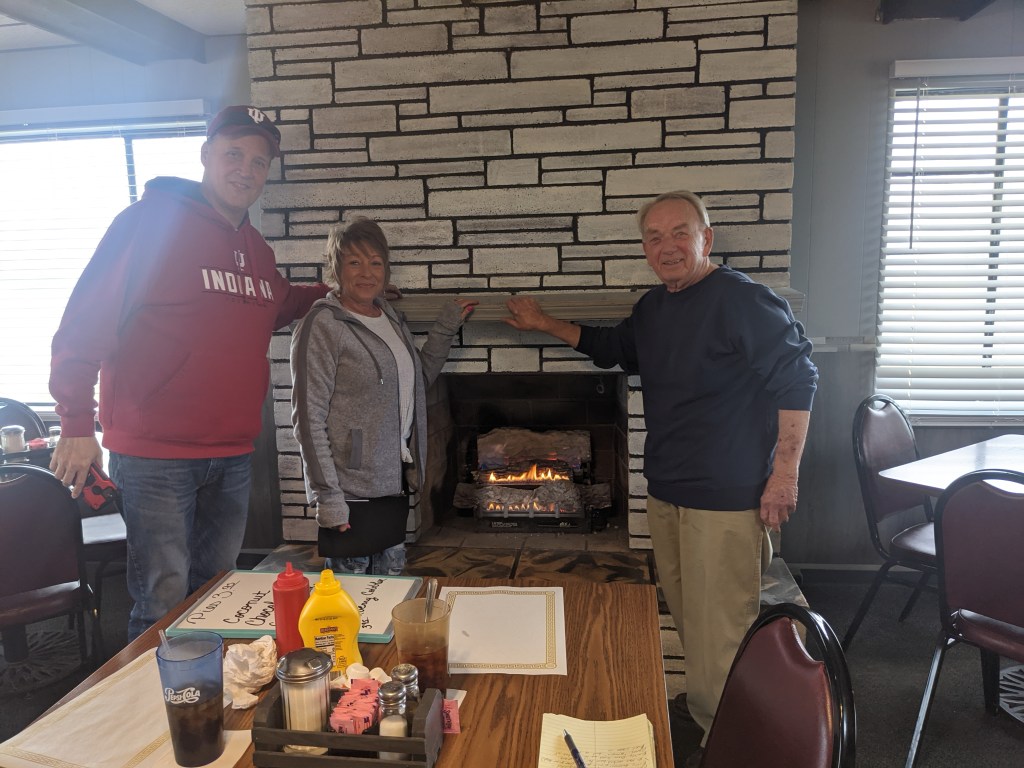

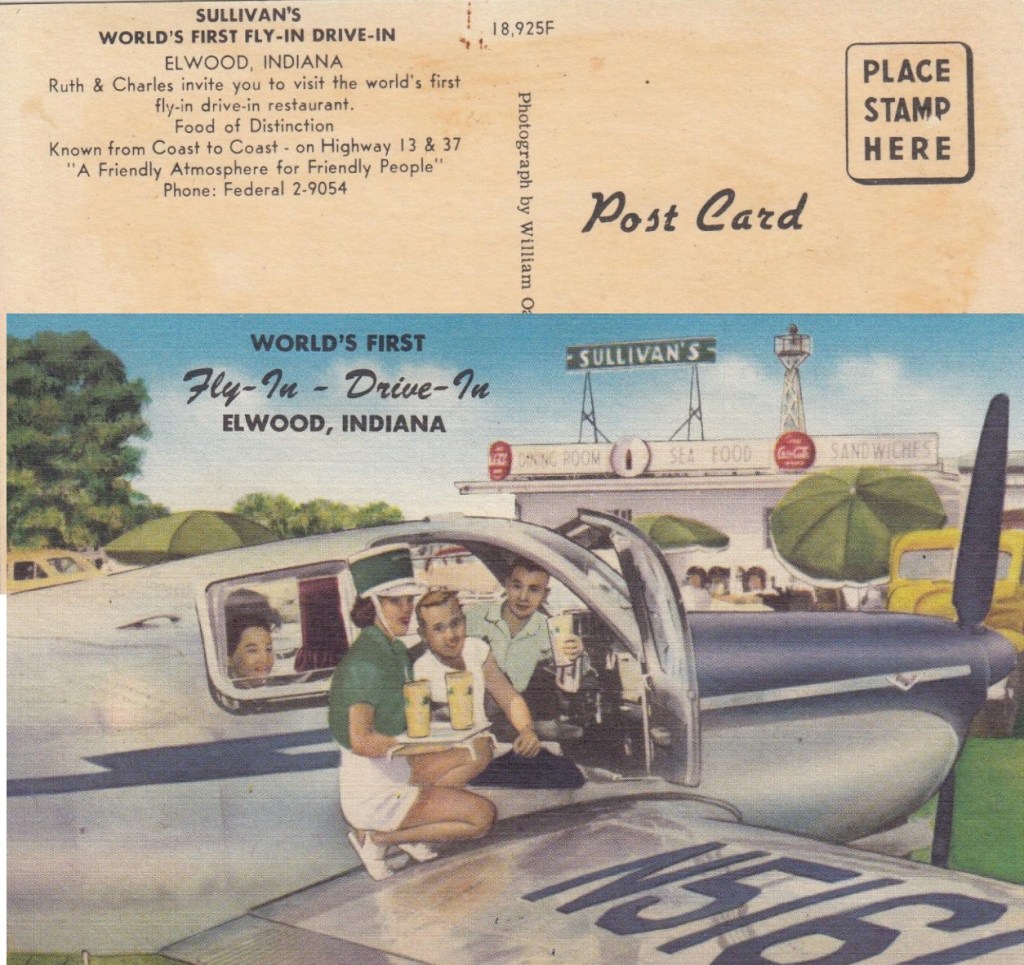

A couple of weeks ago, my wife Rhonda and I drove about 40 miles north of Irvington to Elwood to visit the world’s first (and only) fly-in drive-in restaurant. Resting just northeast of the intersection of Indiana 37 and 13, the Airport Restaurant is located at 10130 State Road 37 on what was once the Elwood Airport. The planes are long gone, and diners no longer rub elbows with pilots, but the Airport Restaurant is still the place where all the locals eat.

The airport was founded just after World War II by Elwood residents Don and Georgia Orbaugh. It featured two grass runways, measuring 2,243 feet and 2,076 feet. The sod landing strips accommodated single-engine planes and their specialty was known as the $100 hamburger. The restaurant did not charge $100 for burgers, but for pilots, that’s what they became. “By the time you get in your airplane, fill it up with gas, and fly a 100 miles, it’s a $100 hamburger,” the old pilot’s joke went. Don and Georgia Orbaugh owned and operated the airport for 56 years before it passed to daughters Ann Brewer and Donna Ewing.

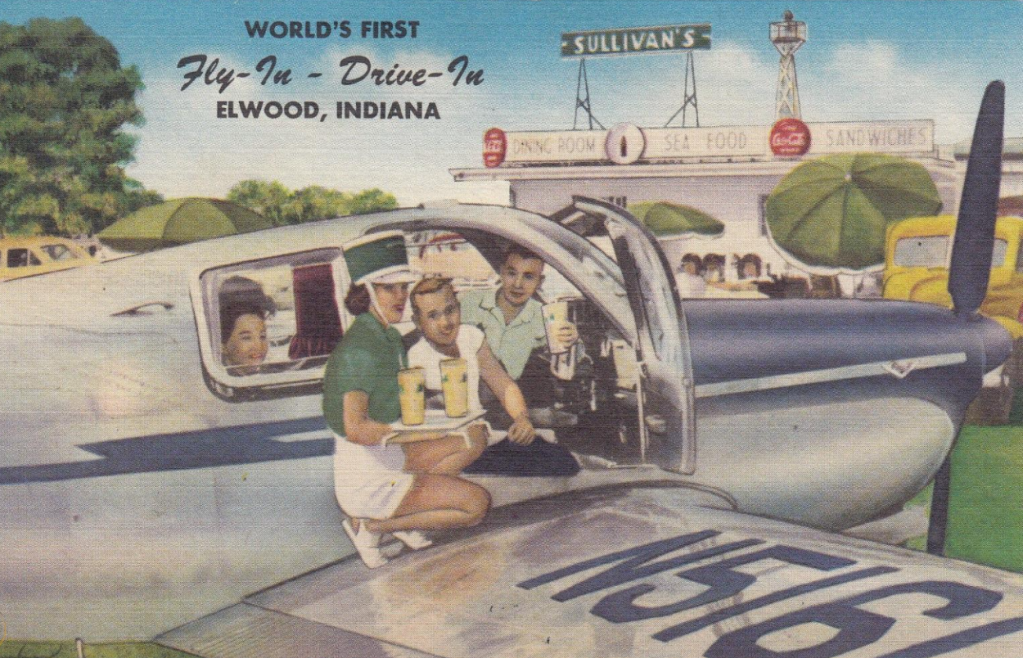

In 1952, “Sullivan’s Airport Restaurant” gained statewide attention when it opened an ice cream shack staffed by pretty young carhops. By 1953, a dining room was added to the shack, and young girls wearing tiny green uniforms with boxy marching band hats served curbside customers in their cars and pilots in their planes. Truth be told, the airport was really a “touch-and-go” facility where pilots practiced their landings and takeoffs. Most pilots only flew into the airport to visit the restaurant and ogle the carhops. By the end of the 50s, the novelty was over. There are a few photos (and at least one postcard) surviving of the Airport Restaurant during its heyday. The photos show the young waitresses in their carhop uniforms and the postcard pictures one of them standing on the wing of an airplane serving food to the pilots inside the cockpit.

Al Swineforth, the current owner of the Airport Restaurant, has a long history in the restaurant business. “I moved to Elwood in 1970. I was a General Manager for Darden Foods in Anderson for 22 years when I retired,” he stated. For those who don’t know, Darden’s family of restaurants features some of the most recognizable and successful brands in full-service dining — Olive Garden, LongHorn Steakhouse, and Cheddar’s to name a few — serving more than 320 million guests annually in over 1,800 restaurants located across North America. Al smiled wryly, then said, “The day I retired, I was driving north on 13 when I stopped at 37 and saw the old Wheeler’s truck stop. I stayed retired for a total of four hours.”

Anyone who has ever driven through northern Hamilton County on State Road 37 knows the old “Wheelers” building. The truck stop opened in 1940 as “Scotty’s Inn.” This was back when SR 37 was the main route between Fort Wayne and Indy, so Scotty’s became a well-known stop for truckers, local farmers, and travelers alike. It featured gas pumps, a restaurant on the main floor, and “tourist rooms” upstairs. Swineforth reopened the restaurant after it sat derelict for many years following a devastating kitchen fire in the 1970s.

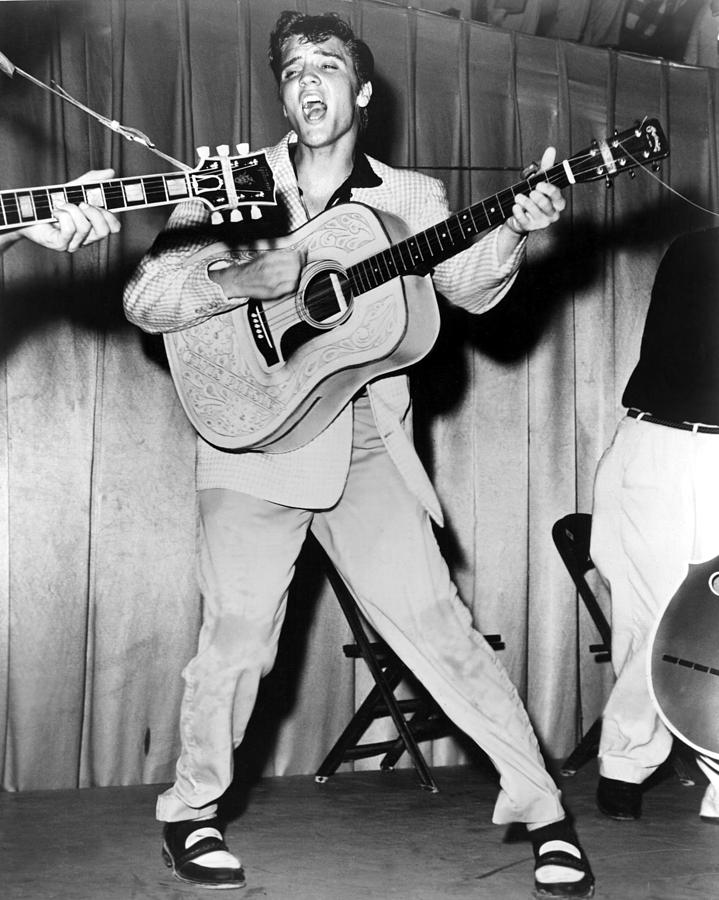

Swineforth recalled that the place was a mess when he took it over. “Oh the stories that building could tell,” he said. “Those rooms upstairs were rented to truckers by the hour,” he whispered with a wink. “You know, Elvis Presley came through there once back in the 1950s.” Swineforth ran his restaurant from 1993 to 1999 before the ancient infrastructure finally forced him to shut it down. The building remained vacant for nearly two decades before it reopened in 2018 as Mercantile 37.

After Swineforth closed his restaurant at the old Wheelers, he landed in Elwood. “I rent the building from the Orbaugh daughters. I own the name and everything within these walls, but the 74-acre airport property remains in the Orbaugh family,” Al noted. “Every Governor since Otis Bowen has stopped in here. Well, except Evan Bayh, he was never here. Mike Pence came in here all the time before he became Vice-President.” Al said, “He used to hold meetings right over there at that corner table.” Swineforth recalls one Governor’s visit in particular. “Frank O’Bannon came in here once for a meet-and-greet. We were running planes then and there were a couple of pilots in here. The Governor’s bodyguards went out and pulled the car up to leave and while they were gone the Governor said that he’d really like to take a plane ride. Pilot John Ward told him his plane was right outside and the Governor took off out the back door and was circling the runways within minutes.” Al closed by saying, “When those bodyguards came back in to get him, you should have seen the looks on their faces when I pointed to the sky and told them ‘there he goes.’ You couldn’t get away with that nowadays.”

The airport closed for good on September 1, 2008. The former runways were leased to a local farmer, who has since planted them in crops. Statistics from the previous year showed that the airport had 2,604 general aviation aircraft operations, an average of 217 per month. When I asked him how it affected his business, Al replied, “I lost $100,000 overnight.” That wasn’t the only calamity Swineforth had to weather. Like most restaurants, the COVID-19 pandemic nearly devastated the Airport Restaurant. “We never closed during COVID,” he stated. “Oh we shuttered the dining room but we were open for curbside and delivery.” It might surprise some to learn that Swineforth thinks the pandemic actually helped his business. “The community really came through for us. I think they appreciated that we never closed. Our business picked up after we reopened.”

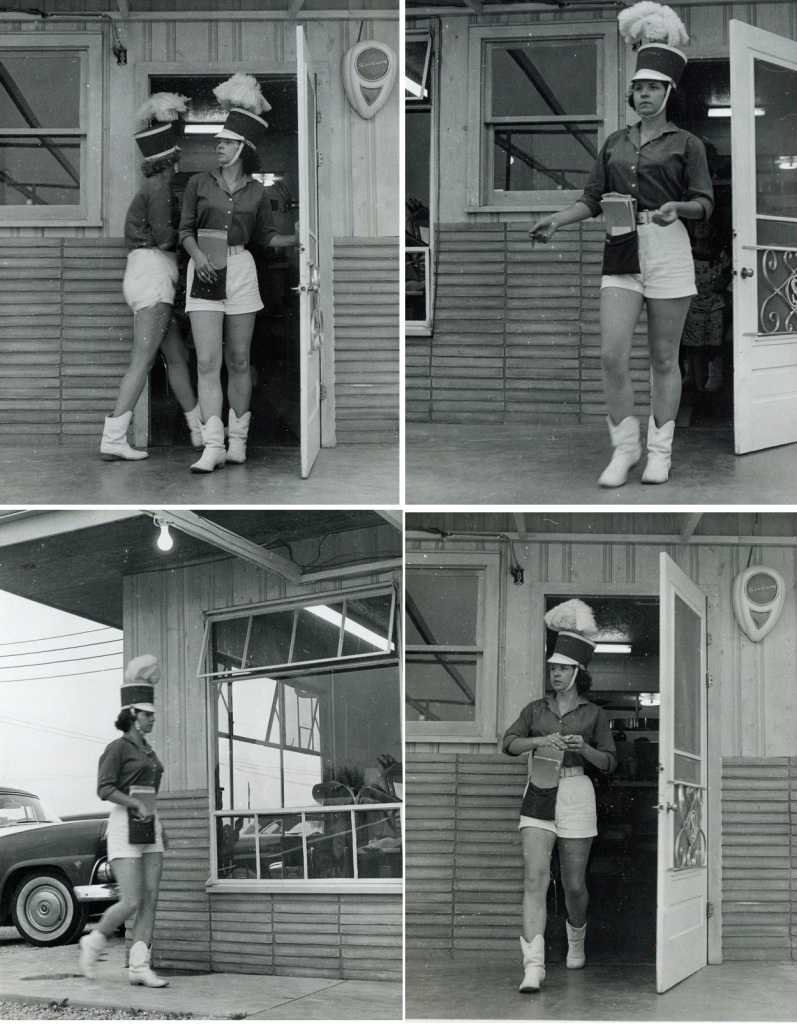

I visited the Airport Restaurant on a weekday and was immediately greeted by owner Al Swineforth. Al insisted that we have lunch before we sat down to chat, his treat. We were seated in the dining room right next to the fireplace. Our waitress Holly Fettig greeted us warmly and informed us that she had worked there since she was 18 years old. “My mom worked here for a few years before I started,” Holly said. “I’ve been here for over 25 years now.” I question that statement because she looks like she would still get carded in any bar she found herself in today.

The menu is full of so many different dishes that it is hard to zero in on any one particular selection. The restaurant fare runs the gamut from Hoosier staples like grilled tenderloins, onion rings, fried green tomatoes, and double-decker hamburgers to steak, chicken and noodles, or fish dinners. Holly informed us that they are “famous for our elk burgers.” Rhonda had broccoli cheddar soup and a grilled ham & cheese sandwich and I opted for a giant hamburger, fries, and chili. Next time, I’m trying that elk burger. We were not disappointed. The restaurant serves breakfast, lunch, and dinner with homemade pies also available.

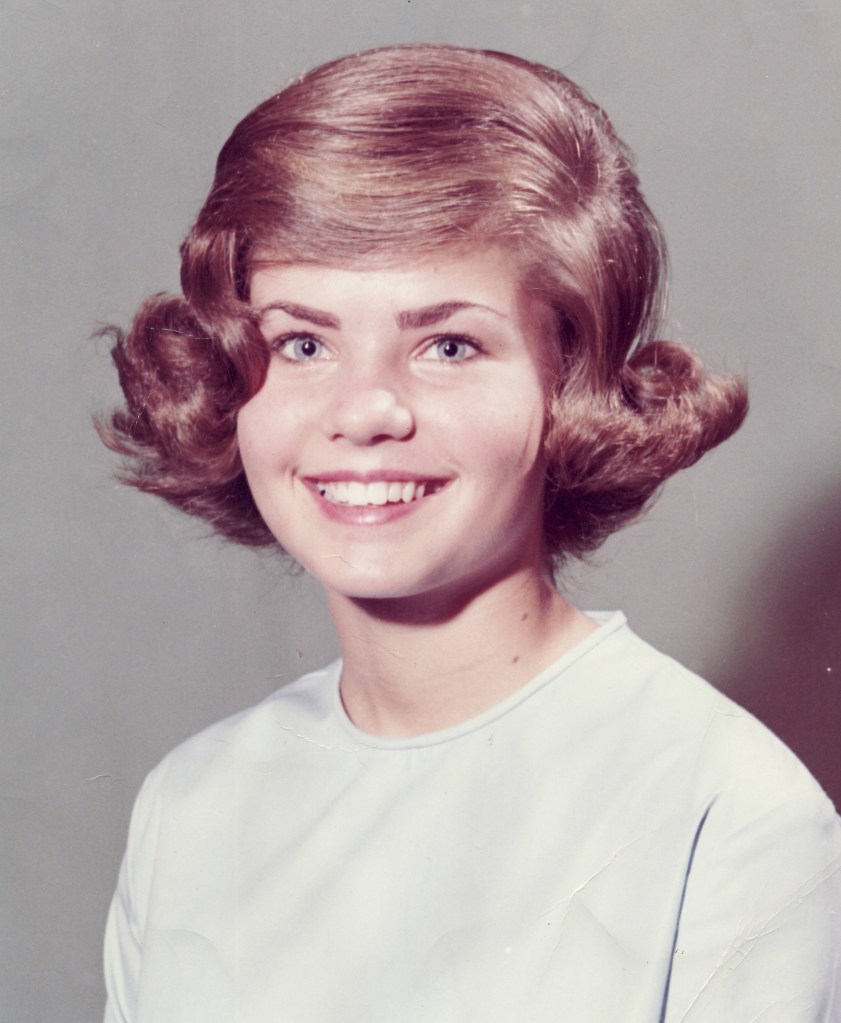

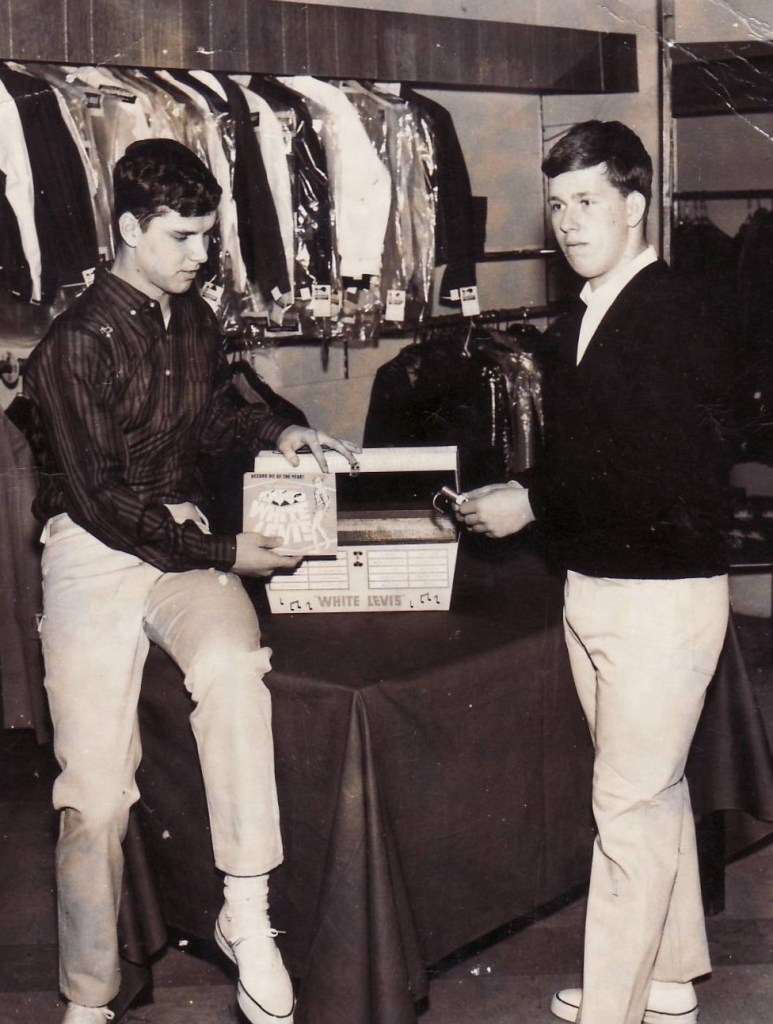

After lunch, we sat down with Al and Holly and explained the reason for our visit. Turns out that the restaurant has a family connection. My mother-in-law, Kathy Hudson, worked at the restaurant in 1968 at a time when it was being managed by my wife’s great-grandfather, Virgil Edgar Musick. Rhonda’s dad, Ron Musick, has told us for years about his grandfather and his restaurant and recalled helping with the bookkeeping when he was in high school. “The restaurant was called Musick’s Airport Restaurant back then. Granddad was a musician. He played slide guitar in a band along with running the restaurant.” Ronnie said, “Seemed like he was playing on the radio every weekend on WOWO up in Fort Wayne. He backed up some pretty big-name musicians in his day.”

Kathy told us that she was working as a waitress there when Bobby Kennedy’s campaign flew into Elwood in May of 1968. “I don’t remember Bobby being there, but his advance guys were there, all dressed up in suits and dark sunglasses. They asked me if I wanted to go for an airplane ride and I told them, ‘Well, only if my husband can come along.’ The advance men told her, ‘Sure, he can sit on the wing.’ Did I mention that Kathy, former homecoming queen at Anderson Highland High School back in 1964, is quite the looker? The fireplace table was important because Rhonda’s only memory of the restaurant centers around a photo of her and grandmother Nina Pace standing in front of it. Rhonda told Al, “But I remember it as red brick, not white.” Al explained, “Yes it was red but we painted it white when we remodeled the place several years ago.”

The planes don’t come here anymore and the runways were plowed over years ago. However, evidence of the airport survives in the many pictures of planes, parked on the grassy runways, taken back in the 1960s and 70s that now line the walls of the restaurant. My father-in-law, Keith Hudson, remembered tooling around Elwood back when it was a working airport. “We used to cut through here by driving up the runway back then. I still eat there from time to time.” When I mentioned Hud’s name to Al, he said, “Oh yeah, I know Keith from Bernie’s bar in Frankton.” Turns out that before he ran the Airport Restaurant, Virgil Musick ran the 128-club in Frankton. Seems like Al Swineforth knows everyone in Madison County. And as for those shortcuts through a working airport runway, don’t worry Hud, I think the statute of limitations has run on that by now.