Original publish date: September 19, 2019

Over the past decade there has been a subtle yet perceptible shift in historical genre on the Internet (particularly on Facebook) known as the “Then and Now” movement. If you are a fan of historical photography, or of the time and space continuum theory, then no doubt you have noticed these images. They consist of a blended pair of photographs, usually landscapes or buildings, one old, one new, both morphed into a single image for comparison. They are eerie reminders of a shared place and time probably best described by William Faulkner in his classic Requiem for a Nun as “The past is never dead. It’s not even the past.” If, like me, you’re a fan of this genre you need to thank one man: William A. Frassanito of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Mr. Frassanito first popularized the “then and now” movement in his groundbreaking book “Gettysburg. A Journey in Time“. He followed up that classic with two similar books on Antietam, another on Grant and Lee in Virginia and three more on Gettysburg, including his seminal study of Early Photography at Gettysburg. Mr. Frassanito was among the first to conduct a historical comparison based on identifying topographical elements found in archival photographs that remain consistent on the landscape today. Bill’s work sent a shockwave through the historical community that resonates to this day.

I interviewed Mr. Frassanito at the Adams County Historical Society research center (368 Springs Avenue Gettysburg) a couple times during the past few months. I was in Gettysburg looking for information on Osborn Oldroyd, whose father was a one time Adams County resident and former owner of a textile mill in the county. Most of my readers will recognize the Oldroyd name as a near constant in this writer’s work.  Needless to say, I was pleased with my visit to and pleasantly reminded how invaluable places and people like these are to the preservation and education of history. After the ACHS helped fill in some blanks in my research, I turned my attention to author Bill Frassanito. He is intensely private, yet unassuming and modest in demeanor. Although an author by trade and historian by nature, Mr. Frassanito has the soul of a teacher.

Needless to say, I was pleased with my visit to and pleasantly reminded how invaluable places and people like these are to the preservation and education of history. After the ACHS helped fill in some blanks in my research, I turned my attention to author Bill Frassanito. He is intensely private, yet unassuming and modest in demeanor. Although an author by trade and historian by nature, Mr. Frassanito has the soul of a teacher.

When I asked Mr. Frassanito how he developed the concept fot the modern “then and now” movement so prevalent on the Internet nowadays, he modestly answers, “I’ve always been fascinated by the concept of time and that today is tomorrow’s history. What I tried to do in the use of ‘then and now’ was to have the reader experience the photograph, but it’s not just the ‘then and now’, it’s the maps that allow people to go and stand on the spot and experience what the photographer experienced. So it’s a total picture used in a systematic fashion book after book after book. I didn’t invent the concept, but I took it to a level that was completely unprecedented. When my ‘journey’ book came out in 1975, there were about a dozen modern books on the battle of Gettysburg available. Now there are zillions on every aspect of the battle.”

When asked if there are any more books on the horizon, Bill answers, “My first book came out when I was 28 in 1975 and the last came out in ’97 and I’m through writing. I’ve done everything I’ve wanted to do. I was much sharper 20 years ago than I am now. I’m especially pleased that part of my legacy are people like Garry Adleman and Tim Smith, and they constantly mention my work, so I do have a legacy. I’m not going to be around forever but I do know that 100 years from now there will be a group of people that are very familiar with the role my pioneering work played, so the average person probably won’t know about me but the experts will know indefinitely. I laid the foundation so when new stuff surfaces they will know how to fit it in.”

When asked what first drew him to Gettysburg, he explains, “My first trip to Gettysburg was in 1956 when I was nine years old, and I was just awed by all the monuments, cannons and stuff. I started my research when I was a kid and much of the research for Journey in Time was done when I worked it into a Masters thesis (he is a proud Gettysburg College alum). “When you went to Gettysburg College, I was the high school class of ’64, college class of ’68, at that time all the male students had to take either phys ed or ROTC for two years, after that you made the decision whether you continued on to advanced ROTC, then you were a part of the Army and you got paid. From there you are committed to, after graduation, serving for two years as a second lieutenant, then on to grad school.”

When asked what first drew him to Gettysburg, he explains, “My first trip to Gettysburg was in 1956 when I was nine years old, and I was just awed by all the monuments, cannons and stuff. I started my research when I was a kid and much of the research for Journey in Time was done when I worked it into a Masters thesis (he is a proud Gettysburg College alum). “When you went to Gettysburg College, I was the high school class of ’64, college class of ’68, at that time all the male students had to take either phys ed or ROTC for two years, after that you made the decision whether you continued on to advanced ROTC, then you were a part of the Army and you got paid. From there you are committed to, after graduation, serving for two years as a second lieutenant, then on to grad school.”

Frassanito continues, “I was accepted to Gettysburg College my senior year in high school. I went to high school in Long Island. I spent a weekend at the college as a senior. I had some time off and I visited the Red Patch Antique Shop and I asked if they had any old photos and he (the shop owner) brought out a basket full of cased images. Among the photos was an outdoor daguerreotype, which is very rare. I opened up this quarter plate daguerreotype, it was a farmer sitting on a bench with a horse in front of the barn. I asked how much and he said a $1.50, which doesn’t sound like much, but it was worth more back then. On the inside of the case was the name of the photographer, “G.J. Goodrich York, Pa.” Years later I discovered that Glenalvin J. Goodrich was one of the few black photographers in Pennsylvania. But because of the battle, he moved to Michigan.”

Glenalvin, son of former-slave, opened his first photo studio at the age of 18 in 1847 and later operated his studio out of the Goodridge residence on East Philadelphia Street. Mr. Frassanito has already allowed the daguerreotype to be used in two different books asking only that credit for the photo be given to the Frassanito collection. “Just last year I was contacted by someone who wanted to purchase the daguerreotype and I said I’m sorry it’s not for sale, I have personal attachment to it. His offer kept going up and up and up. His last offer was $10,000. And I told him, no it’s not for sale, I’m sorry. It’s going to go to the Adams County Historical Society. Now, when it is at the Adams County Historical Society, since it’s not Adams County related, if they wanted to make a deal with the York County historical Society, I would have no problem because technically that would be, probably, the most appropriate place.”

Bill’s collecting interests are not solely confined to Gettysburg. “All of my stuff is going to the Adams County Historical Society. It will be called the Frassanito collection. Including all my stuff that goes beyond Gettysburg and Adams County. My interest in military history includes World War I and Franco Prussian war, it’s very expansive.” Mr. Frassanito’s interest in all things military came when he saw the 1956 movie “War and Peace” starring Audrey Hepburn and Henry Fonda and, he states, “from that time on I’ve been fascinated by Russian history including the Crimean War” (October 1853 to February 1856 in which the Russian Empire lost to an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, Britain and Sardinia).

Bill’s collecting interests are not solely confined to Gettysburg. “All of my stuff is going to the Adams County Historical Society. It will be called the Frassanito collection. Including all my stuff that goes beyond Gettysburg and Adams County. My interest in military history includes World War I and Franco Prussian war, it’s very expansive.” Mr. Frassanito’s interest in all things military came when he saw the 1956 movie “War and Peace” starring Audrey Hepburn and Henry Fonda and, he states, “from that time on I’ve been fascinated by Russian history including the Crimean War” (October 1853 to February 1856 in which the Russian Empire lost to an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, Britain and Sardinia).

“It was 1968, my senior year, my parents came to visit me from Long Island. We rode around the countryside and stopped at an antique shop in New Oxford. I asked my standard question, do you have any old photographs? The shopowner brought out this brown paper bag full of old photos removed from photo albums. Apparently he would sell the empty albums. There were 130 Carte de Visites, I asked how much and he said a dollar.” Among those CDV’s was a rare photo of an identified Franco-Prussian soldier. But more importantly was the discovery of two photos from a New York City gallery. One signed on front “G.G. Sickles”, the other “Susan M. Sickles.” Frassanito thought no more about the photos until years later when he discovered that these were the parents of the famous Gettysburg General Dan Sickles, who lost a leg in the Peach Orchard during the battle of Gettysburg. “I eventually made a connection with the Sickles family and learned that they had no photographs of these relatives.” says Frassanito, “Turns out I have the only photos. They were just stuck in this old brown paper bag.” he says with a chuckle.

Bill then details a chance meeting he had with Pres. Dwight D Eisenhower while serving in advanced ROTC as a junior at Gettysburg College. “As fate would have it, they lined us up by size, and as I was the shortest cadet in the unit, I was positioned at the far left of the line, which turned out to be the sweet spot where all the cameras and newspapermen were positioned. Much to my surprise, Ike stopped in front of me and we had a short conversation while the cameras clicked away. It was not a substantive talk and you could of knocked me over with a feather.” That photo can be found in Mr. Frassanito’s updated Gettysburg Bicentennial Album book available for sale at the Adams County Historical Society.

“I’m the definition of a baby boomer.” Bill reveals, “The war ended in ’45 and the millions of serviceman came home and the boom started in ’46. My pop was in the Navy and he got back from the Pacific in December of ’45 and I arrived exactly 9 months later to join my older brother and my parents. I was born in September 1946. The neat piece of trivia of here is that three months before I was born in June 1946, President Donald Trump was born. Two months before I was born in July 1946 President George W. Bush was born. And one month before I was born in August 1946, President Bill Clinton was born. It’s the first time in American history that we have three presidents not only born in the same year, but born in successive months.” Then, Bill says with a wink, “June, July and August and I’m September, so I’m technically the next president. But I haven’t made my final decision yet.”

Bill continued, “I fortunately survived Vietnam and I put it (his book research) all together when I got out of the Army. I tried to get a job in the museum field but the book took off when I signed with one of the top publishers, Charles Scribner’s. It was later picked up for the Book-of-the-Month club. That became the first of seven books on Civil War photography. I spent eight years and eight months on that project.” One of Bill’s most important discoveries was the “Slaughter Pen” near Devil’s Den. Bill’s book included detailed maps. Bill explains, “The whole purpose of the book was to enable people to re-experience standing where the photographer was. One of the questions I often get is why I don’t update the modern photographs. I’ll never do that as I see them as sort of a time capsule in themselves and I want people to know what the battlefield looked like when I spent five years looking for these spots.”

Bill continued, “I fortunately survived Vietnam and I put it (his book research) all together when I got out of the Army. I tried to get a job in the museum field but the book took off when I signed with one of the top publishers, Charles Scribner’s. It was later picked up for the Book-of-the-Month club. That became the first of seven books on Civil War photography. I spent eight years and eight months on that project.” One of Bill’s most important discoveries was the “Slaughter Pen” near Devil’s Den. Bill’s book included detailed maps. Bill explains, “The whole purpose of the book was to enable people to re-experience standing where the photographer was. One of the questions I often get is why I don’t update the modern photographs. I’ll never do that as I see them as sort of a time capsule in themselves and I want people to know what the battlefield looked like when I spent five years looking for these spots.”

Another of Mr. Frassanito’s photographic discoveries was to identify the family of General John Reynolds pictured in Devil’s Den on the battlefield. When asked if there have been any more discoveries of historical photography at Gettysburg, Bill states, “As far as early photography of Gettysburg is concerned, the last major discovery were those photos of the posed soldiers in Devil’s Den (made by Frassanito). The hunt for the “Harvest of Death” is still going on. Those are the photos of the union dead. I established that these two camera angles showed the same group of bodies looking at a different direction.” Mr. Frassanito has not been able to pinpoint the exact location for this famous photograph, although many others have approached him with locational suggestions over the years.

Frassanito notes that the publication of that photo started a search that is still going on 44 years later. There have been two dozen sites that have been suggested as the site of the photograph. “When people make their discoveries it becomes a religious experience. Every one of those sites has major problems. As far as I’m concerned I don’t want to see a faulty location declared the site and have the search end. That’s the biggest mystery for Civil War photography at Gettysburg. And I’m hoping that one day a pristine 1863 version of the original stereoview or negative surfaces.”

Frassanito notes that the publication of that photo started a search that is still going on 44 years later. There have been two dozen sites that have been suggested as the site of the photograph. “When people make their discoveries it becomes a religious experience. Every one of those sites has major problems. As far as I’m concerned I don’t want to see a faulty location declared the site and have the search end. That’s the biggest mystery for Civil War photography at Gettysburg. And I’m hoping that one day a pristine 1863 version of the original stereoview or negative surfaces.”

Previous to my April visit, I shared, as part of my research at the Adams County Historical Society, the fact that I had just come from researching at the Smithsonian, the Library of Congress and the House Where Lincoln Died. While in Washington, my steward for the day was a young woman named Janet Folkerts who had just learned that she was now the curator in charge of the Vietnam War Memorial wall museum. I was aware that Bill had served (with distinction) during the Vietnam War, so I asked him about his service. He detailed his term of service in Vietnam and shared his story about the wall.

Bill was discharged in August of 1971 and upon returning to Gettysburg in November, Bill began taking all of his “modern” photographs used in his groundbreaking book. “I was there (Vietnam) in ’70 and ’71. I was assigned to the 525 military intelligence group in Saigon. I worked at MACV (aka ‘Mac-Vee’) headquarters (Military Assistance Command, Vietnam) which was the nerve center for all of Indochina. I worked at the highest level of military intelligence, so we knew what was really going on. We knew that the war was a lost cause once the US troops left. We had very little faith in the South Vietnamese, there was corruption from the top down. So anyway, I worked in the safest place in Vietnam.” However, once Bill’s work shift was over and he departed, he was on his own.

“I lived about 2 miles away in kind of a slum area of Saigon, it was a hotel we rented from the Vietnamese called Horn Hall. On the main floor was a narrow lobby, and there were two shifts requiring a duty officer, you had to spend six hours just sitting there. You had a pistol and if anything happened, you were in charge. One of the shifts was midnight to six. On the 16th of December 1970 I was assigned night duty at MACV headquarters so my name was removed from the night duty at Horne Hall. Later, we got a phone call that a bomb had gone off that night at Horne Hall and the Lieutenant on duty was instantly killed. And I realized that had I been sitting there, all of my discoveries would have gone with me. And these classic photos of the 24th Michigan and 1st Minnesota would still be misidentified.”

“I lived about 2 miles away in kind of a slum area of Saigon, it was a hotel we rented from the Vietnamese called Horn Hall. On the main floor was a narrow lobby, and there were two shifts requiring a duty officer, you had to spend six hours just sitting there. You had a pistol and if anything happened, you were in charge. One of the shifts was midnight to six. On the 16th of December 1970 I was assigned night duty at MACV headquarters so my name was removed from the night duty at Horne Hall. Later, we got a phone call that a bomb had gone off that night at Horne Hall and the Lieutenant on duty was instantly killed. And I realized that had I been sitting there, all of my discoveries would have gone with me. And these classic photos of the 24th Michigan and 1st Minnesota would still be misidentified.”

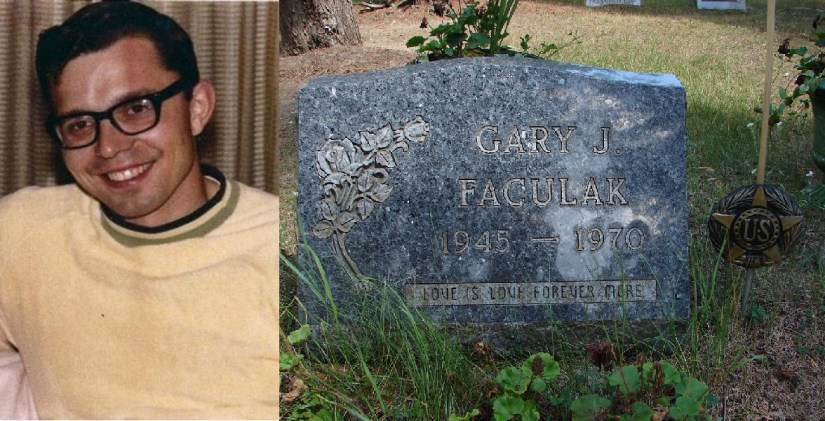

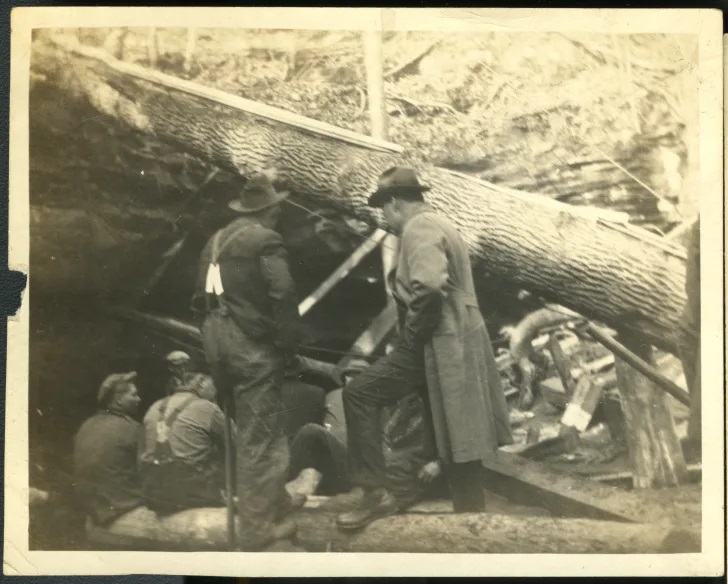

At this point, Bill slides over to the computer and, in somewhat surreal fashion, Googles his own name to find the photo online showing the devastation that may have been his own fate. “It was a 35 pound satchel charge and that’s the seat I could’ve been sitting in. It blew out both walls of this narrow hall and that’s where they found the body of the Lieutenant.” I asked if he knew the Lieutenant, “No, I socialized with the people I worked with, but the officers quarters (where the bomb exploded) you just slept there basically. I knew my roommate but I didn’t know the name of the Lieutenant and I didn’t want it bouncing around in my head for the rest of my life so I made no effort to remember it. Years later, I visited the wall down in Washington and I found out that the 58,000+ names are in chronological order. So I was curious to see, if I had died, where my name would be. There was only one 1st Lieutenant killed in military region three on the night of December 16th, so I found the spot and wrote the name of the officer down. I started wondering what it would have been like for people visiting the wall to see my name there.”

Unsurprisingly, Bill researched the soldier (Gary J. Faculak) and contacted his family to learn more about the man; his hopes, aspirations and goals. Turns out the dead soldier was from Boyne City, Michigan and aspired to own a tour boat and lead tours on Lake Charlevoix (Michigan’s third largest lake) when he got out of the Army. Lt. Faculak is buried in Maple Lawn cemetery in Boyne City. Ironically, the cemetery made headlines in May of 2011 when two special Civil War veterans were honored not far from Lt. Faculak’s grave, thanks to the Robert Finch Camp No. 14 of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War. Two Native American Indian sharpshooters (John Jacko and William Isaacs), buried a century ago in unmarked graves, finally received their long overdue headstones. Both soldiers were members of Co. K of the Michigan 1st Sharpshooters, the only all-Indian unit in the Union Army east of the Mississippi. Both men were also members of the G.A.R.

What’s more, Bill learned that he was not the only one to narrowly escape death that day. Turns out another young officer (Van Buchanan) had switched shifts with Lt. Faculak that night. “If it hadn’t been for the Internet, I would never have been able to make the connection,” says Bill. Well, Mr. Frassanito, if it hadn’t been for your dogged detective work for a group of dusty, old, mislabeled, long-forgotten photographs, we would have never made the connection either. Well done, soldier, well done.

Our tour guide explains, “The house had been in the Peter Baker family since 1847.” As a youngster, Dean listened to stories under the old tree that is still there near the house. He continues, “This is where the original guides used to gather under the tree and smoke cigars and drink a little whiskey. The Baker boys were bachelors and always had time to tell stories.” Dean has an encyclopedic knowledge of the battle, but also has personal stories told to him by the legendary figures of this battlefield town. As a youngster, Dean recalls visits by “Pappy Rosensteel who had a huge collection of battlefield relics that he took me to on many occasions.” George D. Rosensteel (1884-1971) had a fantastic lifetime collection of battle relics and displays, including the interpretive Battle of Gettysburg map, acquired by the National Park Service for use in the Gettysburg National Military Park museum and visitor center from 1974-2008. “But they didn’t get it all,” Dean says, “They didn’t get it all.”

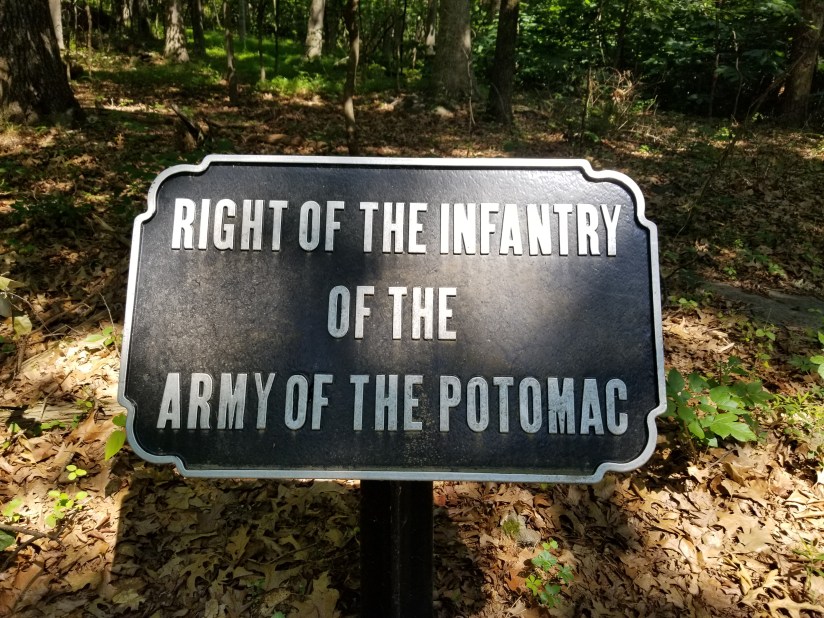

Our tour guide explains, “The house had been in the Peter Baker family since 1847.” As a youngster, Dean listened to stories under the old tree that is still there near the house. He continues, “This is where the original guides used to gather under the tree and smoke cigars and drink a little whiskey. The Baker boys were bachelors and always had time to tell stories.” Dean has an encyclopedic knowledge of the battle, but also has personal stories told to him by the legendary figures of this battlefield town. As a youngster, Dean recalls visits by “Pappy Rosensteel who had a huge collection of battlefield relics that he took me to on many occasions.” George D. Rosensteel (1884-1971) had a fantastic lifetime collection of battle relics and displays, including the interpretive Battle of Gettysburg map, acquired by the National Park Service for use in the Gettysburg National Military Park museum and visitor center from 1974-2008. “But they didn’t get it all,” Dean says, “They didn’t get it all.” We are standing at the base of Wolf Hill near Rock Creek on the far right of the Union Army infantry line; the sounds of traffic whizzing by us on the Baltimore Pike, but it feels like we have traveled back in time. Dean leads us up the slope, we walk about a football field’s length away as he stops in some shady spot, relights his pipe, and explains about cattle grazing in the woods or points out where soldiers were once temporarily buried. This amazing octogenarian halts often, not for his sake but for ours. He climbs these slopes with the agility of a man half his age. He is not winded, but we are.

We are standing at the base of Wolf Hill near Rock Creek on the far right of the Union Army infantry line; the sounds of traffic whizzing by us on the Baltimore Pike, but it feels like we have traveled back in time. Dean leads us up the slope, we walk about a football field’s length away as he stops in some shady spot, relights his pipe, and explains about cattle grazing in the woods or points out where soldiers were once temporarily buried. This amazing octogenarian halts often, not for his sake but for ours. He climbs these slopes with the agility of a man half his age. He is not winded, but we are. As we reach the entrance to Lost Avenue, Dean explains with a sweep of his hand, “This was an orchard at the time of the battle, the bodies of many soldiers were buried in rows right over there.” Former resident Cora Baker’s (1890-1977) grandmother told how, after the battle as the bodies were picked up for reburial, “the grass just quivered with lice and bugs where they laid and when the soldiers would roll up their bedrolls in the morning, the grass was alive with lice and bugs from the bodies of the living soldiers as well.”

As we reach the entrance to Lost Avenue, Dean explains with a sweep of his hand, “This was an orchard at the time of the battle, the bodies of many soldiers were buried in rows right over there.” Former resident Cora Baker’s (1890-1977) grandmother told how, after the battle as the bodies were picked up for reburial, “the grass just quivered with lice and bugs where they laid and when the soldiers would roll up their bedrolls in the morning, the grass was alive with lice and bugs from the bodies of the living soldiers as well.” Upon entering Lost Avenue, Dean explains that General Neill was sent here to guard the rear flank of the Union Army and, most importantly, to protect the Baltimore Pike. Dean states, “When I was a boy I used to visit Lost Avenue with Arthur Baker (1893-1970), who as a lad had walked the fields with the old soldiers that visited the property and actually fought over this ground. Arthur would go and grab a bayonet, left here after the battle, from one of the farm buildings. He’d attach it to his walking stick, hide behind the stone wall and charge out screaming the Rebel Yell.”

Upon entering Lost Avenue, Dean explains that General Neill was sent here to guard the rear flank of the Union Army and, most importantly, to protect the Baltimore Pike. Dean states, “When I was a boy I used to visit Lost Avenue with Arthur Baker (1893-1970), who as a lad had walked the fields with the old soldiers that visited the property and actually fought over this ground. Arthur would go and grab a bayonet, left here after the battle, from one of the farm buildings. He’d attach it to his walking stick, hide behind the stone wall and charge out screaming the Rebel Yell.” Dean maintains the avenue. “The park service never comes out here. Most of the guides have never been out here. The only one I’ve ever seen up here was Barb Adams.” Lost Avenue is the last section of the battlefield that looks exactly as it did when the soldiers fought, and died, here. Dean further explains, “Monuments were set on grass lined strips with no thought of ever paving them. The roads you know now were paved much later. Lost Avenue is the last “pristine section” of unpaved roadway. The 40 foot wide strip is lined by the original stone fence that the 2nd Virginians & 1st North Carolinians fought behind. It was made of field stones picked up by farmers over the years and predates the battle. The second stone wall, the 1895 section, was built later after Sickles took over.”

Dean maintains the avenue. “The park service never comes out here. Most of the guides have never been out here. The only one I’ve ever seen up here was Barb Adams.” Lost Avenue is the last section of the battlefield that looks exactly as it did when the soldiers fought, and died, here. Dean further explains, “Monuments were set on grass lined strips with no thought of ever paving them. The roads you know now were paved much later. Lost Avenue is the last “pristine section” of unpaved roadway. The 40 foot wide strip is lined by the original stone fence that the 2nd Virginians & 1st North Carolinians fought behind. It was made of field stones picked up by farmers over the years and predates the battle. The second stone wall, the 1895 section, was built later after Sickles took over.”

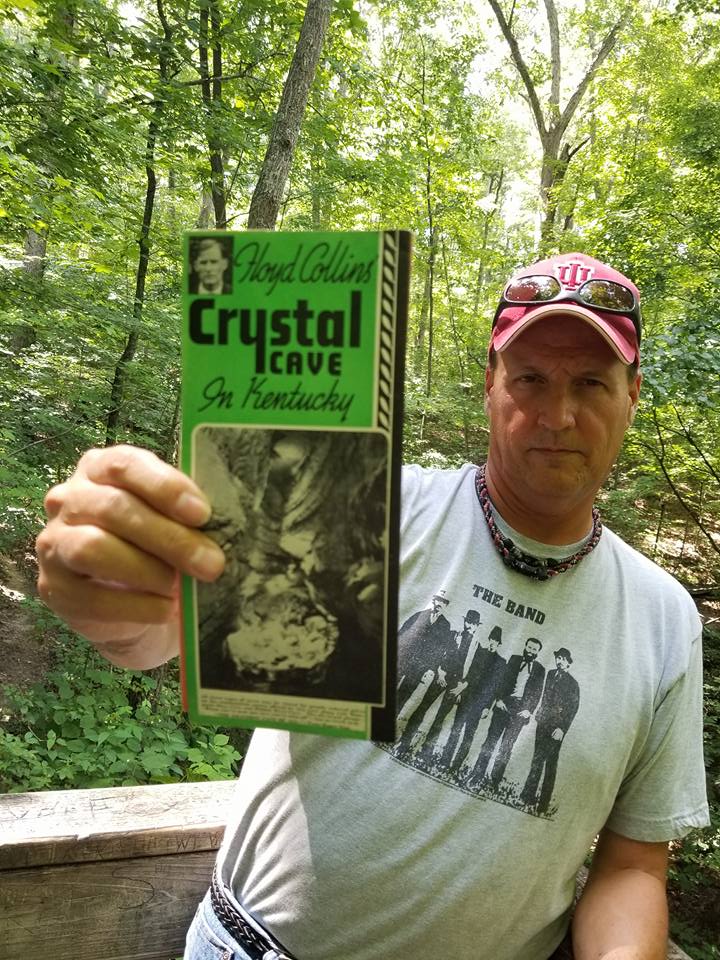

As springtime returned to the Kentucky hills, the Collins family melted back into their rocky, hillside farm; no richer from the limelight. After the crowds departed, locals saw old man Lee scouring the rescue site for glass bottles to return for deposit. Two years later, in 1927, a struggling Lee Collins sold Crystal Cave to a dentist named Dr. Harry B. Thomas. The sale included White Crystal cave and the burial site of Floyd Collins. Lee’s $10,000 deal with Dr. Thomas included a morbid clause: that his son’s body could be exhumed and displayed in a glass-covered coffin inside the cavern. The enterprising country doctor quickly dug the dead man up and placed Floyd’s encased body on display in Crystal Cave. The gimmick worked and, much to the horror of Floyd’s friends and the Collins family, tourists flocked to Crystal Cave to view the embalmed body of the man now known as the “Greatest Cave Explorer Ever Known.”

As springtime returned to the Kentucky hills, the Collins family melted back into their rocky, hillside farm; no richer from the limelight. After the crowds departed, locals saw old man Lee scouring the rescue site for glass bottles to return for deposit. Two years later, in 1927, a struggling Lee Collins sold Crystal Cave to a dentist named Dr. Harry B. Thomas. The sale included White Crystal cave and the burial site of Floyd Collins. Lee’s $10,000 deal with Dr. Thomas included a morbid clause: that his son’s body could be exhumed and displayed in a glass-covered coffin inside the cavern. The enterprising country doctor quickly dug the dead man up and placed Floyd’s encased body on display in Crystal Cave. The gimmick worked and, much to the horror of Floyd’s friends and the Collins family, tourists flocked to Crystal Cave to view the embalmed body of the man now known as the “Greatest Cave Explorer Ever Known.”

Sometime in the wee hours of March 18-19, 1929, Floyd’s body was stolen. The grave robbers “rescued” Collins’s corpse with the intentions of chucking him into the Green River, but Floyd’s body got tangled in the heavy underbrush and Dr. Thomas recovered the remains from a nearby field, minus his injured left leg. The remains were re-interned in a chained casket and placed in a secluded portion of Crystal Cave dubbed the “Grand Canyon”. A half-a-year later, the Great Depression blanketed the country and Floyd Collins’ saga was now a forgotten footnote. Times in Cave City got tough. Tourism plummeted-the same limelight that drew tourists innumerable to the Kentucky cave region now caused visitors to avoid it. As tourism dollars dried up, the sleazy tricks of local cave owners intensified. That feeling pervades Cave City today.

Sometime in the wee hours of March 18-19, 1929, Floyd’s body was stolen. The grave robbers “rescued” Collins’s corpse with the intentions of chucking him into the Green River, but Floyd’s body got tangled in the heavy underbrush and Dr. Thomas recovered the remains from a nearby field, minus his injured left leg. The remains were re-interned in a chained casket and placed in a secluded portion of Crystal Cave dubbed the “Grand Canyon”. A half-a-year later, the Great Depression blanketed the country and Floyd Collins’ saga was now a forgotten footnote. Times in Cave City got tough. Tourism plummeted-the same limelight that drew tourists innumerable to the Kentucky cave region now caused visitors to avoid it. As tourism dollars dried up, the sleazy tricks of local cave owners intensified. That feeling pervades Cave City today.

However, Paula’s younger sister Gail, (a Harvard graduate and architect who lives in Oakland, CA) caught the Collins’ family fever and is a caver. Paula explains, “she got the spelunking gene – she and her husband belonged to a Spelunking Club when she was in her 20s.” Gail states, “Floyd Collins was in a forbidden “sandstone” cave which is the most fragile of rocks. I only went into Limestone caves which are more stable. The biggest concern about spelunking in Indiana & Kentucky is flash flooding. We only did caving during the dry months and mostly winter, when the ground is frozen for 5-8 weeks at a time. I spent New Yea’s Eve in a cave with Chuck (her husband) and our Spelunking group one year. One of my last spelunking adventures I was pulled out of a very wet cave entry, by a caving buddy, 6’6″, 250 lb former Marine, because the makeshift tree trunk ladder was missing two rungs. He reached into the hole and used one arm to hoist me out. A harrowing adventure indeed.” Seems that Gail narrowly escaped the fate of her long lost cousin Floyd.

However, Paula’s younger sister Gail, (a Harvard graduate and architect who lives in Oakland, CA) caught the Collins’ family fever and is a caver. Paula explains, “she got the spelunking gene – she and her husband belonged to a Spelunking Club when she was in her 20s.” Gail states, “Floyd Collins was in a forbidden “sandstone” cave which is the most fragile of rocks. I only went into Limestone caves which are more stable. The biggest concern about spelunking in Indiana & Kentucky is flash flooding. We only did caving during the dry months and mostly winter, when the ground is frozen for 5-8 weeks at a time. I spent New Yea’s Eve in a cave with Chuck (her husband) and our Spelunking group one year. One of my last spelunking adventures I was pulled out of a very wet cave entry, by a caving buddy, 6’6″, 250 lb former Marine, because the makeshift tree trunk ladder was missing two rungs. He reached into the hole and used one arm to hoist me out. A harrowing adventure indeed.” Seems that Gail narrowly escaped the fate of her long lost cousin Floyd.

An enterprising local scientist jerry-rigged a wire to a lightbulb that was sent down to not only illuminate the hole, but also to keep Floyd warm. An amplifier on the other end was closely monitored by technicians hunched over an electronic box under the tarp. A cross between a telegraph and a stethoscope, it detected vibrations whenever Collins moved and was viewed as a desperate lifeline. The amplifier crackled 20 times per minute, which the scientist claimed as proof positive that Collins was still alive and breathing. Alive and breathing, but still trapped.

An enterprising local scientist jerry-rigged a wire to a lightbulb that was sent down to not only illuminate the hole, but also to keep Floyd warm. An amplifier on the other end was closely monitored by technicians hunched over an electronic box under the tarp. A cross between a telegraph and a stethoscope, it detected vibrations whenever Collins moved and was viewed as a desperate lifeline. The amplifier crackled 20 times per minute, which the scientist claimed as proof positive that Collins was still alive and breathing. Alive and breathing, but still trapped.

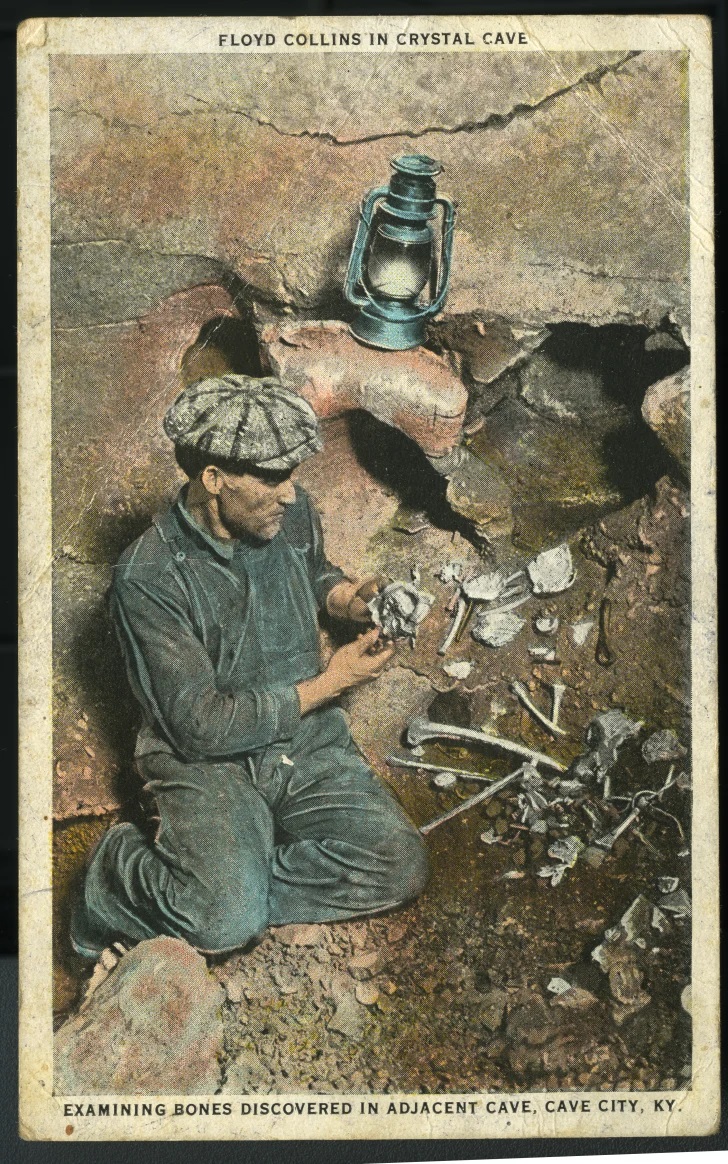

Floyd Collins is one of those people. Collins was long, lean, logical and legendary. He remains history’s most famous spelunker. Not only because of the way he lived, but also because of the way he died. William Floyd Collins was born on July 20, 1887 in Auburn, Kentucky. He was the third child of Leonidas Collins and Martha Jane Burnett. Collins had five brothers and two sisters, including another brother named Floyd. Which was not uncommon for the time as frontier families often feared that a child might not survive to adulthood.

Floyd Collins is one of those people. Collins was long, lean, logical and legendary. He remains history’s most famous spelunker. Not only because of the way he lived, but also because of the way he died. William Floyd Collins was born on July 20, 1887 in Auburn, Kentucky. He was the third child of Leonidas Collins and Martha Jane Burnett. Collins had five brothers and two sisters, including another brother named Floyd. Which was not uncommon for the time as frontier families often feared that a child might not survive to adulthood. The biggest business in the area was Mammoth Cave, but there were others: Great Onyx Cave, Colossal Cavern, Great Crystal Cave, Dorsey Cave, Salt Cave, Indian Cave, Parlor Cave, Diamond Cave, and Doyles Cave. These holes were all owned and operated by men who charged admission to the visiting tourists who were more than happy to pay for the privilege. At the center of it all was Cave City. Here was the depot that brought wealthy visitors in on the hour, all hungry for adventure. And Cave City residents were more than happy to assist these gullible visitors by relieving them of their cash. As we will see later in this article, not much has changed in 200 years.

The biggest business in the area was Mammoth Cave, but there were others: Great Onyx Cave, Colossal Cavern, Great Crystal Cave, Dorsey Cave, Salt Cave, Indian Cave, Parlor Cave, Diamond Cave, and Doyles Cave. These holes were all owned and operated by men who charged admission to the visiting tourists who were more than happy to pay for the privilege. At the center of it all was Cave City. Here was the depot that brought wealthy visitors in on the hour, all hungry for adventure. And Cave City residents were more than happy to assist these gullible visitors by relieving them of their cash. As we will see later in this article, not much has changed in 200 years.

Collins first tasted celebrity when he discovered Crystal Cave in 1917 when he discovered Crystal Cave (now part of the Flint Ridge Cave System of the Mammoth Cave National Park). Twenty-seven year old Collins had chased a ground hog down a hole on his father’s farm. The hole turned out to be a passage to a large cavern Floyd called “White Crystal Cave”. He owned one half and his father owned the other. They went into business, selling options on the cave to a neighbor named Johnny Gerald who’d made a little money buying and selling tobacco. Johnny and Floyd took turns; one of them stood on the side of the road and tried to talk the tourists inside; the other guided them through the cave’s.

Collins first tasted celebrity when he discovered Crystal Cave in 1917 when he discovered Crystal Cave (now part of the Flint Ridge Cave System of the Mammoth Cave National Park). Twenty-seven year old Collins had chased a ground hog down a hole on his father’s farm. The hole turned out to be a passage to a large cavern Floyd called “White Crystal Cave”. He owned one half and his father owned the other. They went into business, selling options on the cave to a neighbor named Johnny Gerald who’d made a little money buying and selling tobacco. Johnny and Floyd took turns; one of them stood on the side of the road and tried to talk the tourists inside; the other guided them through the cave’s. Soon the Collins family found themselves smack dab in the middle of the “Cave Wars” of the early 1920s, where Central Kentucky cave owners and explorers entered into a bitter competition to exploit the bounty of caves for commercial profit. Trouble was, Crystal Cave was the last cave on the road from Cave City. By the time tourists discovered it, they were out of money and interest. During the Cave War years, cave owners competed bitterly among each other in order to bring in visitors. The most common tactic was to deploy a man, referred to as a “capper”, who would suddenly rush out of the bushes, hop onto your car’s running board along the rugged road out to Mammoth to excitedly inform you that Mammoth had collapsed or was under quarantine from Consumption (now known as Tuberculosis) and would persuade you to visit their cave instead.

Soon the Collins family found themselves smack dab in the middle of the “Cave Wars” of the early 1920s, where Central Kentucky cave owners and explorers entered into a bitter competition to exploit the bounty of caves for commercial profit. Trouble was, Crystal Cave was the last cave on the road from Cave City. By the time tourists discovered it, they were out of money and interest. During the Cave War years, cave owners competed bitterly among each other in order to bring in visitors. The most common tactic was to deploy a man, referred to as a “capper”, who would suddenly rush out of the bushes, hop onto your car’s running board along the rugged road out to Mammoth to excitedly inform you that Mammoth had collapsed or was under quarantine from Consumption (now known as Tuberculosis) and would persuade you to visit their cave instead.

Floyd was encased under a 4′ x 4′ square, two ton block of solid limestone ceiling, the sidewalls of the tunnel were composed of loose stones, pebbles, sand and mud. Floyd was careful to avoid bumping or displacing anything likely to cause a collapse. Collins made it through, muddy, soaked and sweating, after leaving his securely attached rope for a future trip into the 60-foot precipice he had yet to see. He wriggled head first back into the tight gravelly crevice leading to the steep, serpentine chute he’d just come in by. Pushing the kerosene lantern ahead of him as far as he could, he would then twist and squirm, shrugging ahead inch by inch till reaching the lantern before repeating the pattern by pushing ahead. Suddenly, Floyd’s lantern fell over, broke and went out.

Floyd was encased under a 4′ x 4′ square, two ton block of solid limestone ceiling, the sidewalls of the tunnel were composed of loose stones, pebbles, sand and mud. Floyd was careful to avoid bumping or displacing anything likely to cause a collapse. Collins made it through, muddy, soaked and sweating, after leaving his securely attached rope for a future trip into the 60-foot precipice he had yet to see. He wriggled head first back into the tight gravelly crevice leading to the steep, serpentine chute he’d just come in by. Pushing the kerosene lantern ahead of him as far as he could, he would then twist and squirm, shrugging ahead inch by inch till reaching the lantern before repeating the pattern by pushing ahead. Suddenly, Floyd’s lantern fell over, broke and went out.