Original publish date: July 23, 2020

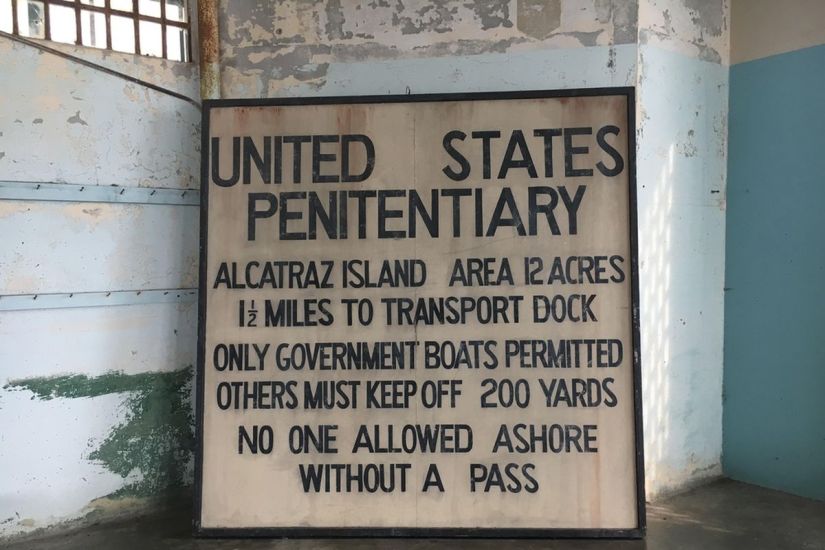

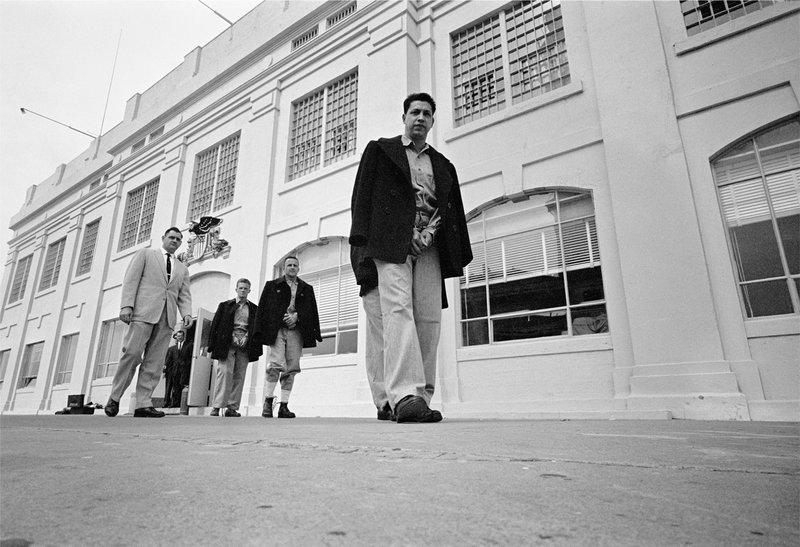

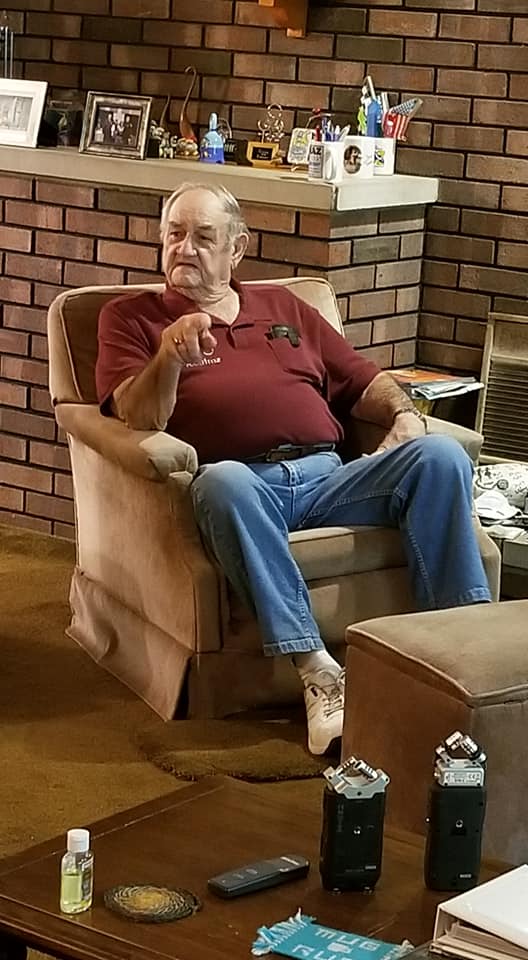

Jim Albright was on duty the night the most famous escape from Alcatraz took place. On June 11, 1962, Frank Morris, Clarence Anglin and his brother John escaped through a hole in the back of their cells, the details of which were chronicled in Clint Eastwood’s 1979 film, “Escape From Alcatraz.” Albright recalled the escape in his 2008 book, “Last Guard Out. A Riveting Account By The Last Guard To Leave Alcatraz” (available at Amazon), “The movie showed them escaping off Broadway and that is not correct. In real life they escaped off Seedy Avenue (outside of B Block).” Jim also points out that the movie showed Eastwood stealing a pair of fingernail clippers off the Warden’s desk, “This would not have been necessary as each inmate was issued a pair when they first arrive at the prison.”

On the night of the escape, Jim recalled, “I had been over in town playing ball and I stepped in a gopher hole and twisted my knee, so they give me some crutches. The next morning (after the escape was discovered), I’m crutching up the hill when I run into the Lieutenant and he says ‘we got some missing’ and orders me to watch the back of the cell house.” Later, Jim went inside the cellhouse to “see what was going on.” He looked in Anglin’s cell and saw the false head. “They got dummy heads up there now that look like I made them. The dummy head I saw that morning looked very real. They did a good job, in fact, when I saw it I thought I had the wrong cell, it looked that real.”

Also in his book, Jim vividly remembers the events leading up to the bustout (“I told them those blankets should not be there”), the escape (“After the escape I was placed on roof detail after night fell, with a pistol and flashlight. I couldn’t flash very often because of limited mobility with crutches.”) and the aftermath (“The inmates had a field day teasing, laughing, comments, etc., toward the guards in the immediate time after the escape.”). “John Anglin was the older brother and John worked for me in the clothing room, so I knew John real well,” Jim believes, “I strongly feel the Anglin brothers probably killed (Frank) Morris to lesson the weight of the raft, and they in turn drowned and washed out to sea…I think about it even after all these years and realize that I too was a part of all of this.” The after effects are still visible. Several times during the story, Jim would stop, shake his head, and say “Them damn blankets.”

Likewise, Cathy recalls the escape from her unique perspective. “I was downstairs with the kids visiting with Betty Miller and we heard this alarm go off. Well, that means you don’t leave where you’re at and I’m down there and I’ve got two kids in diapers and didn’t have any extra diapers so we used towels for diapers until I could go. They searched Betty’s place and then they searched my apartment. But as far as being afraid, I never was, I really felt safer there than I did some other places.”

When I asked Jim about the current trend of tearing down monuments, he recalled the Native American Indian occupation of Alcatraz that took place from 1969 to 1971, years after the Albrights’ left the island. “When the original water tower was replaced after it was rusting away and pieces were falling off of it, they hired a guy, a former kid named Tom Reeves, Jr. who was teenager living on the island when I was there, his dad worked in the hospital as an MTA, his stepmom worked in town as a nurse.” the old guard chuckles as a memory bubbles up, “Tom had a little scheme going when he was in high school, everybody wanted to go to Alcatraz. All of his buddies, everybody in the school wanted to go to Alcatraz. Tom would say ‘I will take you to Alcatraz for two bucks’ so he’d get 3 or 4 guys, get two bucks a piece, bring ’em over and show ’em the island and take ’em back. The Warden found out about it and he wasn’t happy.”

After the laughter died down, Jim continued, “Tom grew up and became an engineer. He has an office in San Francisco, Seattle and somewhere in Hawaii, he was that big. So he engineered the repair of that water tower to make it look just as it did when we were there so that it would hold up. And it looked like new. And then they went and put Indian Graffiti back on it. And I asked (National Park Service Ranger) John Cantwell why they did that and Cantwell’s answer was, ‘Jim, love it or hate it, that is part of our history.'” Jim points out that Reeves, Jr. and his company restored the water tower and helped preserve several of the decaying buildings, including the steel tie-rods used to shore up the Warden’s House that was burnt during the Indian occupation, “at no charge, he did all that for free, he didn’t charge ’em a dime.” Jim and the Alcatraz alumni association wanted to place a plaque near the water tower thanking Reeves, Jr., as a former resident and benefactor, but the Park Service wouldn’t let them.

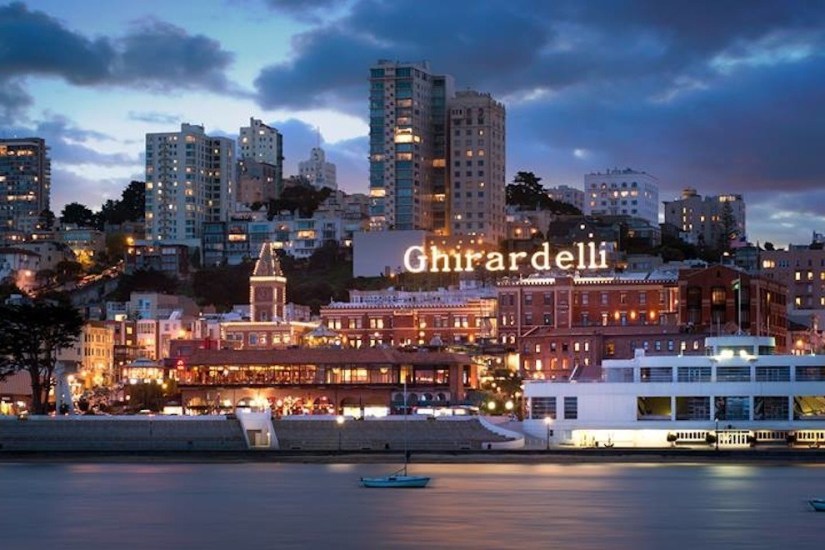

Jim’s recollections about his time on the island are limitless, he can affirm or deny legends about the island with ease. He relates details as if they happened yesterday. “The best cell placement on the island was the second tier because you could look out to see and hear San Francisco. On New Years especially, you could hear the parties and watch the party boats go past. When I was there, Ghiardelli Chocolate factory was still operational and you could smell that chocolate cooking when the breeze was just right.” He continues, “Al, you’ll like this, when I was in the tower, if one of those boats got too close to the island, I’d warn them with a bullhorn and if they didn’t listen, I could fire a shot across their bow. They moved then,” says the veteran guard. The prisoners were aware of the rumor that the island was patrolled by sharks, “Well the prisoners heard the rumor that the guards went down and caught all the sharks and cut the left fin off to make them swim in a circle around the island and we guards didn’t do anything to change their mind.”

Jim’s recollections about his time on the island are limitless, he can affirm or deny legends about the island with ease. He relates details as if they happened yesterday. “The best cell placement on the island was the second tier because you could look out to see and hear San Francisco. On New Years especially, you could hear the parties and watch the party boats go past. When I was there, Ghiardelli Chocolate factory was still operational and you could smell that chocolate cooking when the breeze was just right.” He continues, “Al, you’ll like this, when I was in the tower, if one of those boats got too close to the island, I’d warn them with a bullhorn and if they didn’t listen, I could fire a shot across their bow. They moved then,” says the veteran guard. The prisoners were aware of the rumor that the island was patrolled by sharks, “Well the prisoners heard the rumor that the guards went down and caught all the sharks and cut the left fin off to make them swim in a circle around the island and we guards didn’t do anything to change their mind.”

Jim recalls patrolling the perimeter of the island and occasionally finding relics left over by military personnel during the time Alcatraz was in operation as a military fort guarding the bay from the Civil War up into World War II. Jim would see the old tokens gleaming in the moonlite at water’s edge, “I found script, I guess you’d call it. I think I’ve still got a dime, a fifty cent piece and a quarter around here somewhere.” He continues, “the guys would fish, there was a bout a half a dozen of them, down below the industries building. When you were dock and patrolman, there was a list, when you walked into the dock office, and when you saw the stripe bass running, you looked on that list and you’d call those guys who wanted to fish, anytime day or night, and you could make another round and when yo came back there could be anywhere from ten to thirty guys down there fishing. They made a Formica chute where they’d filet them right there on the spot and give the scraps to the seagulls. Quite often, you could help yourself to as many filets as you wanted. The head chef loved it cause they’d catch enough to feed the whole main line of prisoners.” I asked Jim if he ate the same meals the convicts ate. “When I first started there, I went thru the line and took my food back to a table in the kitchen. then they built us an officer’s dining room upstairs. The food was good.” Jim says the Alcatraz convicts, “had the best food in the prison service. Good food keeps trouble down.”

Jim recalls patrolling the perimeter of the island and occasionally finding relics left over by military personnel during the time Alcatraz was in operation as a military fort guarding the bay from the Civil War up into World War II. Jim would see the old tokens gleaming in the moonlite at water’s edge, “I found script, I guess you’d call it. I think I’ve still got a dime, a fifty cent piece and a quarter around here somewhere.” He continues, “the guys would fish, there was a bout a half a dozen of them, down below the industries building. When you were dock and patrolman, there was a list, when you walked into the dock office, and when you saw the stripe bass running, you looked on that list and you’d call those guys who wanted to fish, anytime day or night, and you could make another round and when yo came back there could be anywhere from ten to thirty guys down there fishing. They made a Formica chute where they’d filet them right there on the spot and give the scraps to the seagulls. Quite often, you could help yourself to as many filets as you wanted. The head chef loved it cause they’d catch enough to feed the whole main line of prisoners.” I asked Jim if he ate the same meals the convicts ate. “When I first started there, I went thru the line and took my food back to a table in the kitchen. then they built us an officer’s dining room upstairs. The food was good.” Jim says the Alcatraz convicts, “had the best food in the prison service. Good food keeps trouble down.”

Cathy chuckles as she recalls Blackie Audett (a longtime convict who worked in the kitchen). “Whenever I baked cookies, I’d lay them out on the window sill to cool. Every time I baked cookies, there would be 3 or 4 officers, I counted 10 one time, that would knock on the door and say, ‘Hey you’re making cookies, I want a few.’ And I asked Jim how did they know? Well, come to find out, that Blackie Audett could look out of that dining room window into my kitchen and see my cookies. Well, that scared the heck out of me. I wondered if he can see in the kitchen window, can he see into the living room window or the bedroom window.” Jim, forever on guard, says, “Yeah, Blackie was there (incarcerated) three times.” Jim also confirms another bit of trivia from Clint Eastwood’s movie, “We had a guy named Ianelli. He was a weightlifter and he had muscles on top of his muscles. I always shook him down extra special and teased him that he was getting lax. They called him Wolf.” Albright confirms that Wolf was a sexual predator as portrayed in the movie and recalled that Wolf was after a young inmate named Robbins who worked back in the “dishtray room”. Jim recalls Wolf was after “Robbie”. “One day Robbie got a pipe and came up behind Wolf hit in the back of the head and damn near killed him. If he (Wolf) had not been in such good shape he would have died. He was sent to our hospital upstairs and brought him about a third of the way back before they shipped him to our medical hospital in Springfield, Missouri. I don’t know if he’s still alive or not but he sure was never the same.”

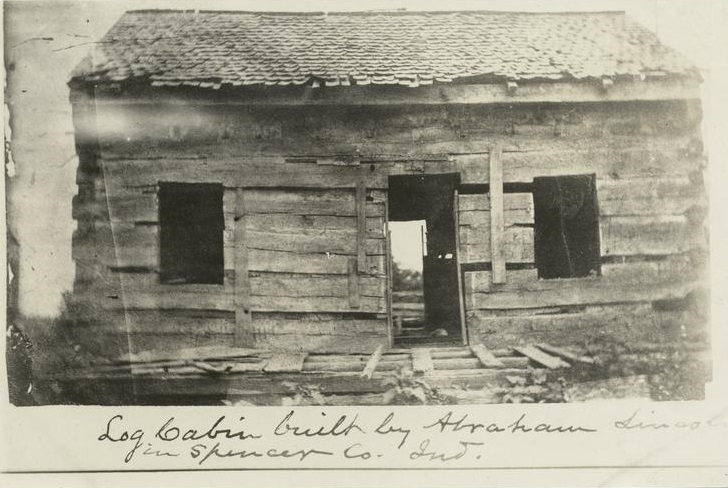

Eventually it was Abraham’s turn to hitch his old mare to the gristmill’s arm. As he tediously walked his horse round and round, he grew impatient at having wasted most of the morning already. He began to apply a hickory switch to the beast’s behind while shouting, “Git up, you old hussy; git up, you old hussy” to keep his horse moving at an accelerated pace. This tactic worked for a short time until the horse had had enough and, just as his young master clucked out the words “Git up”, the horse kicked backwards and hit the boy in the head with a rear hoof. Lincoln was knocked off his feet and into the air, landing some distance away where he came to rest bruised and bloodied. Noah Gordon rushed to the aid of the unconscious young man. Realizing the seriousness of the situation, Gordon picked the boy up and brought him in to his house, placing him on a nearby bed.

Eventually it was Abraham’s turn to hitch his old mare to the gristmill’s arm. As he tediously walked his horse round and round, he grew impatient at having wasted most of the morning already. He began to apply a hickory switch to the beast’s behind while shouting, “Git up, you old hussy; git up, you old hussy” to keep his horse moving at an accelerated pace. This tactic worked for a short time until the horse had had enough and, just as his young master clucked out the words “Git up”, the horse kicked backwards and hit the boy in the head with a rear hoof. Lincoln was knocked off his feet and into the air, landing some distance away where he came to rest bruised and bloodied. Noah Gordon rushed to the aid of the unconscious young man. Realizing the seriousness of the situation, Gordon picked the boy up and brought him in to his house, placing him on a nearby bed. Meanwhile, Dave Turnham, who had come to the mill with Abraham, ran the two miles to get Abraham’s father. Thomas Lincoln rushed to his wagon and lit out to the scene. The elder Lincoln, seeing his son’s grave condition, hauled the injured boy home and put him to bed where the young man remained prone and unconscious all night. Neighbors from the small, close knit community, including mill owner Noah Gordon, gathered at the Lincoln cabin believing Thomas Lincoln’s boy was close to death. The next morning one witness jumped from their seat, pointed and shouted, “Look he’s coming straight back from the dead!” Abraham was shaking and jerking from head to toe when he opened his eyes and finished his cadence from the day before by shouting “You old hussy”.

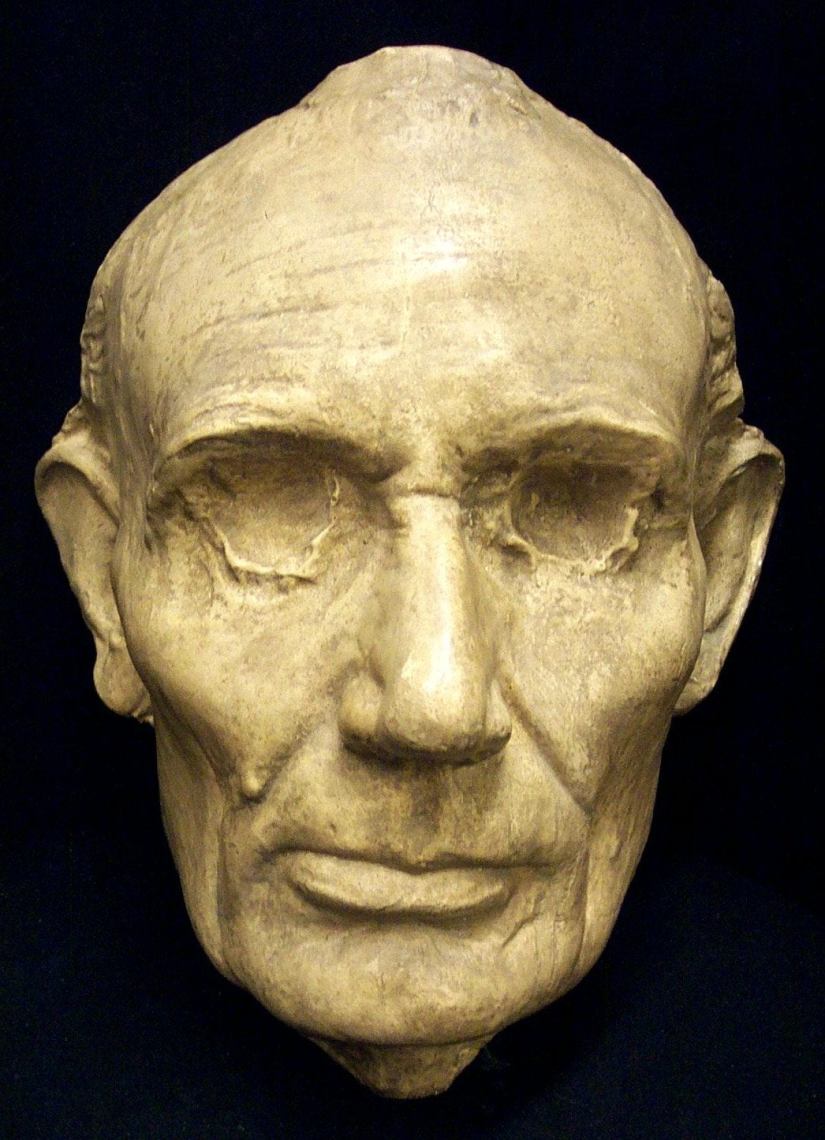

Meanwhile, Dave Turnham, who had come to the mill with Abraham, ran the two miles to get Abraham’s father. Thomas Lincoln rushed to his wagon and lit out to the scene. The elder Lincoln, seeing his son’s grave condition, hauled the injured boy home and put him to bed where the young man remained prone and unconscious all night. Neighbors from the small, close knit community, including mill owner Noah Gordon, gathered at the Lincoln cabin believing Thomas Lincoln’s boy was close to death. The next morning one witness jumped from their seat, pointed and shouted, “Look he’s coming straight back from the dead!” Abraham was shaking and jerking from head to toe when he opened his eyes and finished his cadence from the day before by shouting “You old hussy”. Lincoln’s contemporaries noticed that at times his left eye drifted upward independently of his right eye, a condition doctors diagnosed as “strabismus” but more derisively known as “Lazy Eye”. The resulting affliction results in the eyes failure to properly align with each other when looking straight ahead, particularly when trying to focus on an object. As proof, experts point to the best surviving evidence; two life masks of Lincoln. One a beardless portrait made in April of 1860 and the other, a bearded image made in February of 1865. Laser scans of both masks reveal an unusual degree of facial asymmetry. In short, the left side of Lincoln’s face was much smaller than the right, resulting in the double diagnosis of “hemifacial microsomia” compounded by “strabismus”. The defects join a long list of posthumously diagnosed ailments including smallpox, heart disease, bi-polar disorder and depression that doctors claimed afflicted Lincoln.

Lincoln’s contemporaries noticed that at times his left eye drifted upward independently of his right eye, a condition doctors diagnosed as “strabismus” but more derisively known as “Lazy Eye”. The resulting affliction results in the eyes failure to properly align with each other when looking straight ahead, particularly when trying to focus on an object. As proof, experts point to the best surviving evidence; two life masks of Lincoln. One a beardless portrait made in April of 1860 and the other, a bearded image made in February of 1865. Laser scans of both masks reveal an unusual degree of facial asymmetry. In short, the left side of Lincoln’s face was much smaller than the right, resulting in the double diagnosis of “hemifacial microsomia” compounded by “strabismus”. The defects join a long list of posthumously diagnosed ailments including smallpox, heart disease, bi-polar disorder and depression that doctors claimed afflicted Lincoln. According to a cadre of modern day medical historians, Gardner’s photo is worth a thousand words. Although modern neurologists admit that a positive diagnosis would require a complete examination of the living Lincoln, photographic evidence strongly supports their theory. The mule kick to the forehead undoubtedly fractured the skull at the point of impact, the size and depth of the depression attesting to the incident’s severity. In addition, the nerves behind the left eye were damaged by the violent snapping of the head and neck backward. That whiplash also caused several small hemorrhages in the brainstem resulting in the permanent ocular and facial effects and was likely responsible for Lincoln’s high pitched, rasping voice.

According to a cadre of modern day medical historians, Gardner’s photo is worth a thousand words. Although modern neurologists admit that a positive diagnosis would require a complete examination of the living Lincoln, photographic evidence strongly supports their theory. The mule kick to the forehead undoubtedly fractured the skull at the point of impact, the size and depth of the depression attesting to the incident’s severity. In addition, the nerves behind the left eye were damaged by the violent snapping of the head and neck backward. That whiplash also caused several small hemorrhages in the brainstem resulting in the permanent ocular and facial effects and was likely responsible for Lincoln’s high pitched, rasping voice. Yet another after effect of that boyhood mulekick was noticed by Josiah Crawford, a neighbor from Gentryville, Ind. who employed the boy Lincoln, loaned him books for study. Gentry liked to playfully needle the young railsplitter about the way he “stuck out” his lower lip while in deep concentration. When 35-year-old Lincoln returned to to make a speech in southern Indiana in 1844 for Henry Clay, Crawford noticed Abe’s lower lip still protruded abnormally. When Crawford asked what books he consulted before making the speech, Lincoln replied humorously, “I haven’t any. Sticking out my lip is all I need.”

Yet another after effect of that boyhood mulekick was noticed by Josiah Crawford, a neighbor from Gentryville, Ind. who employed the boy Lincoln, loaned him books for study. Gentry liked to playfully needle the young railsplitter about the way he “stuck out” his lower lip while in deep concentration. When 35-year-old Lincoln returned to to make a speech in southern Indiana in 1844 for Henry Clay, Crawford noticed Abe’s lower lip still protruded abnormally. When Crawford asked what books he consulted before making the speech, Lincoln replied humorously, “I haven’t any. Sticking out my lip is all I need.”

The Reynolds leaflet further reveals,”Father and mother were at Ford’s Theatre the night of the assassination, and although it was late when they returned home, the general excitement of the night had reached our neighborhood. The newsboys shrill cries of “Extra! Extra! President Lincoln Shot” had awakened everybody in the boarding house. I, too, was awake. Young as I was, I realized what dreadful thing had happened, and I lay wide-eyed in my little trundle bed while father and mother related to the others their personal story of the tragedy. Father, accompanied by several of the men guests, went back to the scene and did not return until after the fateful hour of 7:22 the next morning. I remember as clearly as though it were of yesterday, wearing a wide band of black around the sleeve of my bright plaid jacket, and, carried in father’s arms, of passing the somber catafalque in the rotunda of the Capitol, which inclosed (sic) all that was mortal of the beloved Lincoln. A few weeks later I witnessed the Grand Review of the Army – that wonderful spectacle of the returning boys in blue – which took several days in its passing.”

The Reynolds leaflet further reveals,”Father and mother were at Ford’s Theatre the night of the assassination, and although it was late when they returned home, the general excitement of the night had reached our neighborhood. The newsboys shrill cries of “Extra! Extra! President Lincoln Shot” had awakened everybody in the boarding house. I, too, was awake. Young as I was, I realized what dreadful thing had happened, and I lay wide-eyed in my little trundle bed while father and mother related to the others their personal story of the tragedy. Father, accompanied by several of the men guests, went back to the scene and did not return until after the fateful hour of 7:22 the next morning. I remember as clearly as though it were of yesterday, wearing a wide band of black around the sleeve of my bright plaid jacket, and, carried in father’s arms, of passing the somber catafalque in the rotunda of the Capitol, which inclosed (sic) all that was mortal of the beloved Lincoln. A few weeks later I witnessed the Grand Review of the Army – that wonderful spectacle of the returning boys in blue – which took several days in its passing.”

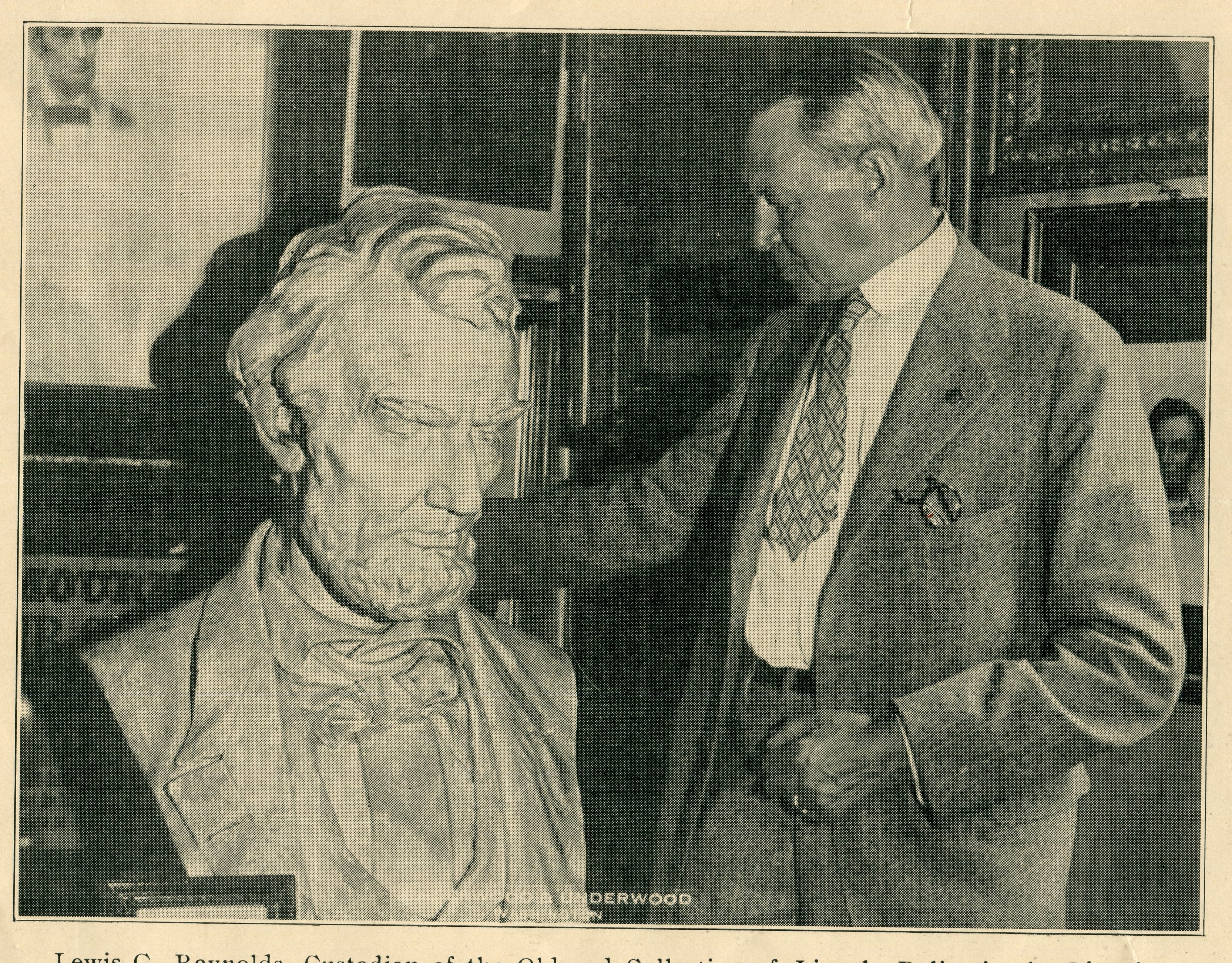

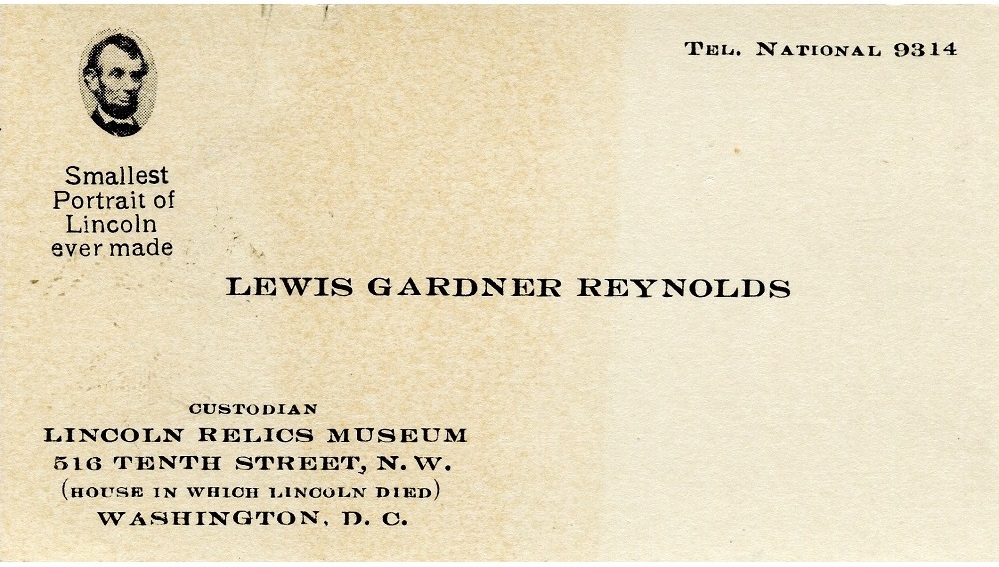

Two decades later, in 1960, the Richmond Palladium-Item newspaper profiled the widow of the former curator, offering new insight. The article is titled: “Local Woman Conducted Tours In House Where Lincoln Died.” It reveals, “Mrs. Reynolds and her husband lived on the second floor of the house at 516 Tenth Street, Washington, DC, at the time Mr. Reynolds was curator of the Oldroyd Lincoln Memorial collection. This was from 1928 through 1936. “I never heard anyone ask Mr. Reynolds a question about Mr. Lincoln he could not answer,” Mrs. Reynolds recalls. Her husband acquired the job as curator when he heard Oldroyd wanted to retire… “I have had visitors say to me doesn’t it give you a creepy feeling?” (sleeping in the house where Lincoln died.) Her answer was always “No.” To the reporter, she said, “I never had a creepy feeling. When I thought about it, it was just a feeling of awe and reverence.” Mr. Reynolds described the collection via radio from the Petersen house several times.“

Two decades later, in 1960, the Richmond Palladium-Item newspaper profiled the widow of the former curator, offering new insight. The article is titled: “Local Woman Conducted Tours In House Where Lincoln Died.” It reveals, “Mrs. Reynolds and her husband lived on the second floor of the house at 516 Tenth Street, Washington, DC, at the time Mr. Reynolds was curator of the Oldroyd Lincoln Memorial collection. This was from 1928 through 1936. “I never heard anyone ask Mr. Reynolds a question about Mr. Lincoln he could not answer,” Mrs. Reynolds recalls. Her husband acquired the job as curator when he heard Oldroyd wanted to retire… “I have had visitors say to me doesn’t it give you a creepy feeling?” (sleeping in the house where Lincoln died.) Her answer was always “No.” To the reporter, she said, “I never had a creepy feeling. When I thought about it, it was just a feeling of awe and reverence.” Mr. Reynolds described the collection via radio from the Petersen house several times.“