Original publish date: December 18, 2016

Original publish date: December 18, 2016

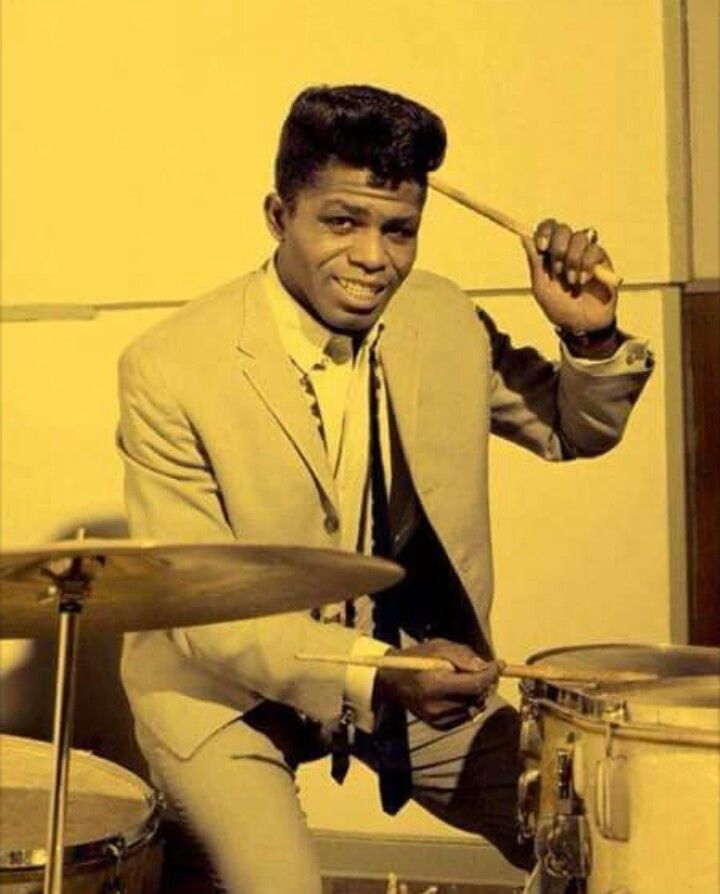

James Brown is remembered as the “Godfather of Soul” for his many contributions to music made during a six-decades-long career. Brown’s influence is a little more complicated than that. Truth is, not only was Brown a music legend, he was a civil rights pioneer. For a time in the 1960s, Brown was among the most important voices in the black empowerment movement. Not only did he change the culture in terms of music but also in terms of civil rights. Everything we now know about funk and hip-hop we learned from James Brown.

During the sixties, Brown’s music served as message of black empowerment and helped keep the peace during that tumultuous decade. Brown embraced the civil rights movement with the same energy and dynamism he devoted to his performances. In 1966, the song “Don’t Be a Drop-Out” urged black children not to neglect their education. In the same year, he flew down to Mississippi to visit wounded civil rights activist James Meredith, shot during his “March Against Fear.”

During that period Brown often provided nighttime performances to ease tensions when the Civil Rights Movement leadership was fracturing and threatening to break apart. As the civil rights leaders were embroiled in internal conflict, Martin Luther King, Jr. famously said, ‘You guys can stay here and argue if you want to, I’m going to go watch James Brown.” Brown recorded hits like “Say it Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)” and “I Don’t Want Nobody to Give Me Nothing (Open Up the Door and I’ll Get it Myself)” that embodied the positive spirit of the Civil Rights Movement in a way speeches, protests and marches never could. Brown later attested those songs “cost me a lot of my crossover audience,” but they shined the light on African-American nationalism and became unifying anthems of the age.

By 1968, James Brown was much more than an important musician; he was an African-American icon. He often spoke publicly about the pointlessness of rioting. In February 1968, Soul Brother No. 1 informed Black Panther leader H. Rap Brown, “I’m not going to tell anybody to pick up a gun.” Brown often canceled his shows to perform benefit concerts for black political organizations like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). In 1968, he initiated “Operation Black Pride,” and, dressing as Santa Claus, presented 3,000 certificates for free Christmas dinners in New York City’s poorest black neighborhoods. He also started buying radio stations.

By 1968, James Brown was much more than an important musician; he was an African-American icon. He often spoke publicly about the pointlessness of rioting. In February 1968, Soul Brother No. 1 informed Black Panther leader H. Rap Brown, “I’m not going to tell anybody to pick up a gun.” Brown often canceled his shows to perform benefit concerts for black political organizations like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). In 1968, he initiated “Operation Black Pride,” and, dressing as Santa Claus, presented 3,000 certificates for free Christmas dinners in New York City’s poorest black neighborhoods. He also started buying radio stations.

On April 5, 1968, African Americans rioted in 110 cities following Dr. King’s assassination the day before. Like Robert F. Kennedy’s speech in Indianapolis the night of the assassination, James Brown hosted a free citywide concert at Boston Gardens aimed at avoiding another racially-charged riot. In the midst of that famous beantown concert, with Boston on the verge of going up in flames, Brown said, ‘I used to shine shoes outside a radio station. Now I own that radio station. That’s black power.’” Many Bostonians credit James Brown for keeping the peace in their city by the sheer force of his music and personal charisma.

However, there was a moment during the show when tensions could have boiled over. As a handful of young black male fans tried to climb on stage, white Boston policemen began forcefully pushing them back. Sensing the volatility of the moment, Brown urged the cops to back away from the stage, then addressed the crowd. “Wait a minute, wait a minute now WAIT!” Brown said. “Step down now, be a gentleman. Now I asked the police to step back, because I think I can get some respect from my own people.” Brown successfully restored order and continued the successful peacekeeping concert in honor of the slain Dr. King.

In 1969, Look Magazine called Brown “the most important black man in America.” In May 1968, President Lyndon Johnson invited Brown to the White House. The following month, the government sponsored him to perform for the troops in Vietnam. James Brown’s life and activism significantly influenced blacks in general, but some of his songs reflect the need for change that was so much a part of the Movement. James Brown used concerts as platforms to spread the philosophy of nonviolence and to bring attention to civil rights organizations. Brown’s music helped promote black consciousness and peace. It also inspired a generation of musicians. Indiana’s own John Mellencamp is probably the best example. Mellencamp has repeatedly acknowledged the influence of James Brown and it shows in his music.

James Brown had three noteworthy phases in his career: from 1962–66 he was ‘Mr. Dynamite”, from 1967–70 he was “Soul Brother No. 1” and from 1970 and beyond he was the “Godfather of Soul”. Sadly, casual fans remember James Brown for three things: his 1985 Rocky IV anthem “Living in America”, his brushes with the law and his hair. The Rocky song is a classic and his cameo in the film allowed viewers a glimpse of the legend that was James Brown. His brushes with the law always seemed a bit overblown to me. After all, he WAS James Brown. His hair, well that’s another story altogether.

There are countless stories about entertainer contract riders. The Beatles demanded a black and white television set and a few Coca-Colas, Elvis demanded 10 soft drinks and 4 cups of water, Van Halen’s rider included requests for “one large tube K-Y Jelly” and “M&Ms- BUT ABSOLUTELY NO BROWN ONES”, Eminem demands 2 cases of Mountain Dew and an assortment of Taco Bell food and Iggy Pop demanded that seven dwarfs greet him in his dressing room (Iggy Pop fans are not surprised).

James Brown’s contract called for a steam iron, ironing board, deli tray with assorted meats and cheeses, coffee, tea, soft drinks (Coke products), Gatorade, champagne (Cristal or Dom), 1 electric golf cart and a hooded hair dryer. Yes, one of those table-model hair dryers like our moms and grandmothers used at the local hair salon. The ones that fit completely over the head like a space helmet. That glorious hair didn’t make itself people. It took hours of painstaking hair engineering to create that unnatural helmet of hair. Plenty of chemicals, hair straightening techniques and, most importantly, a professional-grade rigid hooded hair dryer.

Except for a brief period during the mid-1960s when Brown wore his hair in a traditional afro as a temporary form of protest, for most of his career, James Brown had his hair “marceled” aka straightened or conked. The conk (derived from congolene, a hair straightener gel made from lye) was a hairstyle popular among African-American men. This hairstyle transformed naturally “kinky” hair by chemically straightening it with a relaxer (sometimes the pure corrosive chemical lye), so that the newly straightened hair could be styled in specific ways.

Except for a brief period during the mid-1960s when Brown wore his hair in a traditional afro as a temporary form of protest, for most of his career, James Brown had his hair “marceled” aka straightened or conked. The conk (derived from congolene, a hair straightener gel made from lye) was a hairstyle popular among African-American men. This hairstyle transformed naturally “kinky” hair by chemically straightening it with a relaxer (sometimes the pure corrosive chemical lye), so that the newly straightened hair could be styled in specific ways.

Often, the relaxer was made at home, by mixing lye, eggs, and potatoes, the applier having to wear gloves and the receiver’s head having to be rinsed thoroughly after application to avoid chemical burns. Conks were most often styled as large pompadours although others chose to simply slick their hair back to lie flat on their heads. Conks took a lot of work to maintain: a man often had to wear a do-rag of some sort at home, to prevent sweat or other agents from causing his hair to revert to its natural state prematurely. Also, the style required repeated application of relaxers; as new hair grew in, it too had to be chemically straightened.

In the African American Community of the early 20th century, the conk hairstyle served as a rite of passage from adolescence into adulthood for males. Because of the pain involved in the process, and the possibility of chemical burns and permanent scarring, the conk represented masculinity and virility.

Chuck Berry, Louis Jordan, Little Richard, James Brown, and The Temptations, were well known for sporting the conk hairstyle. The style fell out of popularity when the Black Power movement took hold, and the Afro became the symbol of African pride. Malcolm X, although a conk enthusiast in his youth, condemned the hairstyle as black self-degradation in his autobiography. He decried the conk’s implications about the superiority of a more “white” appearance. The conk is all but extinct as a hairstyle among African-American men today, although more mildly relaxed hairstyles such as the Jheri curl and the S-curl were popular during the 1980s and 1990s.

On December 23, 2006, Brown arrived at his dentist’s office in Atlanta, Georgia for dental implant work. Brown’s dentist observed that he looked “very bad … weak and dazed.” Instead of performing the work, the dentist advised Brown to see a doctor right away about his medical condition. Brown went to the hospital the next day and was admitted for observation and treatment. Brown had been struggling with a noisy cough since returning from a November trip to Europe. The singer had a history of never complaining about being sick and often performed while ill. Brown had to cancel upcoming concerts in Waterbury, Connecticut and Englewood, New Jersey but was confident he would recover in time for scheduled New Year’s Eve shows at the Count Basie Theatre in New Jersey, the B. B. King Blues Club in New York and performing a song live on CNN for the Anderson Cooper New Year’s Eve special. Brown wasn’t called the hardest working man in show business for nothing.

Brown remained hospitalized and his condition worsened throughout the day. On Christmas Day, 2006, Brown died at approximately 1:45 am at age 73. The official cause was congestive heart failure, resulting from complications of pneumonia. Brown’s last words were, “I’m going away tonight,” before taking taking three long, quiet breaths before dying.

James Brown wore his hair in a conk pompadour until the day he died. After Brown’s death, a public memorial service was held at the Apollo Theater in New York City and another at the James Brown Arena in Augusta, Georgia. Brown’s memorial ceremonies were elaborate, complete with costume changes for the deceased and videos featuring him in concert. His body, placed in a Promethean casket—bronze polished to a golden shine—was driven through the streets of New York to the Apollo Theater in a white, glass-encased horse-drawn carriage.

While plans were being made for the funeral, Brown’s family was contacted by Michael Jackson, a lifetime fan and friend. Michael had flown in from Bahrain, where he was living following his 2005 child molestation trial, and he asked to see the Godfather of Soul one last time. Reverend Al Sharpton, who officiated at Brown’s funeral, recalled, “I got a call from the mortician and he asked me if it was alright if Michael Jackson could come by the funeral home and see James Brown’s body. I said, ‘But Michael’s in Bahrain’. And he said, ‘No, he’s here’. A couple of hours later, I called and the mortician said, ‘He just left. He was here (for) about an hour and he was re-combing Mr. Brown’s hair. He felt that I had combed the hair wrong. People didn’t realize he was really into James and he actually styled his hair the way it was buried.”

Sharpton was insistent on making sure Michael stayed in town long enough to rightfully pay respects to the music legend, legal questions notwithstanding. Sharpton added, “I think his plan was to come in the middle of the night, see the body – because James Brown was his idol – and he was going to leave. No one had really seen him since the trial… but we convinced him to stay for the funeral. I told him, ‘Michael, you gotta stay. You’ve gotta re-emerge one day in public.” So in short, the King of Pop was the last person to attend to the Godfather of Soul. Michael would follow his idol to the grave less than three years later.

Original publish date: June 26, 2014

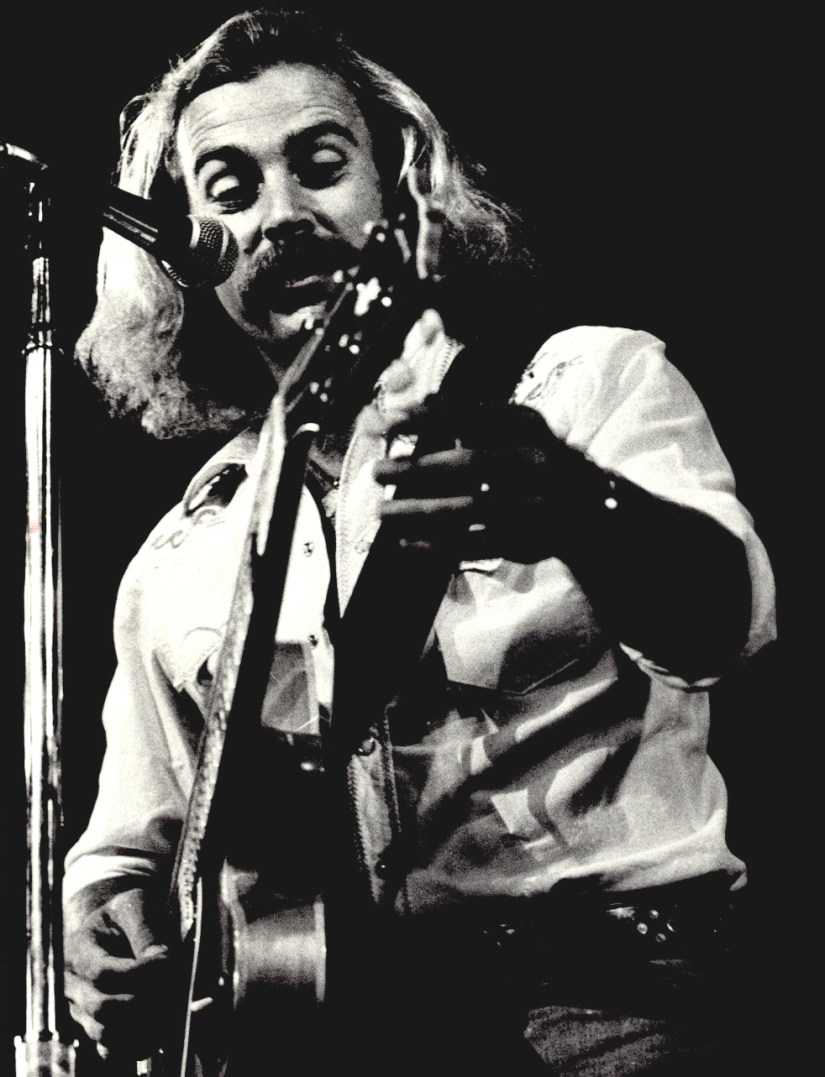

Original publish date: June 26, 2014 Buffett himself tells the story on his fan website, in a 1975 interview for Rolling Stone and in his own biography. “We’re there dining and dancing. Sammy Creason (Drummer) was with me (other accounts say Kris Kristofferson’s bass player Terry Paul was there too), so we provided just a gala of entertainment. Me on acoustic guitar so drunk I couldn’t hit the chords and him just pounding the drums out in 3-quarter time. Ran everybody out. We got the screaming munchies and we were going to Charlie Nickens to eat. And I couldn’t find my rent-a-car, which was parked somewhere amidst thousands of cars in the parking lot of the fabulous, plush King of the Road hotel. It was a little bitty car. It was hiding among many big ones there. And there was a Tennessee Prosecutors convention going on there. If they had made it to room 819 they would’ve had a closed door case.

Buffett himself tells the story on his fan website, in a 1975 interview for Rolling Stone and in his own biography. “We’re there dining and dancing. Sammy Creason (Drummer) was with me (other accounts say Kris Kristofferson’s bass player Terry Paul was there too), so we provided just a gala of entertainment. Me on acoustic guitar so drunk I couldn’t hit the chords and him just pounding the drums out in 3-quarter time. Ran everybody out. We got the screaming munchies and we were going to Charlie Nickens to eat. And I couldn’t find my rent-a-car, which was parked somewhere amidst thousands of cars in the parking lot of the fabulous, plush King of the Road hotel. It was a little bitty car. It was hiding among many big ones there. And there was a Tennessee Prosecutors convention going on there. If they had made it to room 819 they would’ve had a closed door case. I was not scared of this individual. I just thought he was some ex-football player turned counselor. And Sammy said “look whatever damage we did ABC will pay for everything” which was awfully generous of Sammy since he didn’t have the authority to say so. Being a good company man I took up for my company and said “No they won’t. I’m still gonna beat your a*s if you don’t leave us alone”. With that he pulled up then stuck his big head and his hand in and grabbed me by my hair until it separated from my head. I had a big bald spot on the back of it and I looked like a monk for about 3 months. Then he punched Sammy right in the nose. We knew he wasn’t kidding. So Sammy defended himself bravely with a bic pen. He starts stabbing at this man’s arm trying to get it out of the window because we couldn’t start the car because with the new modern features of ‘74 automobiles you can not start your car unless your seat belt’s buckled and we were too drunk to get ours hooked up.

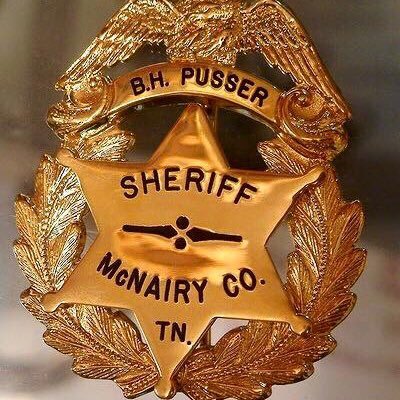

I was not scared of this individual. I just thought he was some ex-football player turned counselor. And Sammy said “look whatever damage we did ABC will pay for everything” which was awfully generous of Sammy since he didn’t have the authority to say so. Being a good company man I took up for my company and said “No they won’t. I’m still gonna beat your a*s if you don’t leave us alone”. With that he pulled up then stuck his big head and his hand in and grabbed me by my hair until it separated from my head. I had a big bald spot on the back of it and I looked like a monk for about 3 months. Then he punched Sammy right in the nose. We knew he wasn’t kidding. So Sammy defended himself bravely with a bic pen. He starts stabbing at this man’s arm trying to get it out of the window because we couldn’t start the car because with the new modern features of ‘74 automobiles you can not start your car unless your seat belt’s buckled and we were too drunk to get ours hooked up. If you don’t recognize the name Buford Pusser, the epic films made about his life might ring a bell. Buford Hayse Pusser was the Sheriff of McNairy County, Tennessee from 1964 to 1970 and the subject of the film “Walking Tall”. Pusser, a 6 feet 6 inch tall 250 pound former professional wrestler, became known for his virtual one-man war on moonshining, prostitution, gambling, and other vices on the Mississippi-Tennessee state-line against the Dixie Mafia and the State Line Mob. By the time he encountered Buffett, Pusser had already killed two men.

If you don’t recognize the name Buford Pusser, the epic films made about his life might ring a bell. Buford Hayse Pusser was the Sheriff of McNairy County, Tennessee from 1964 to 1970 and the subject of the film “Walking Tall”. Pusser, a 6 feet 6 inch tall 250 pound former professional wrestler, became known for his virtual one-man war on moonshining, prostitution, gambling, and other vices on the Mississippi-Tennessee state-line against the Dixie Mafia and the State Line Mob. By the time he encountered Buffett, Pusser had already killed two men. Original publish date: April 3, 2016

Original publish date: April 3, 2016 Original publish date: May 27, 2016

Original publish date: May 27, 2016 Original publish date: November 19, 2008

Original publish date: November 19, 2008