Original Publish Date August 22, 2024.

https://weeklyview.net/2024/08/22/johnny-and-june-carter-cashs-home-nashvilles-graceland-part-1/

In July 2023, my wife and I made the 4 1/2 hour drive down to Nashville, Tennessee, for my birthday. After a few stops in Music City, we made an 18-mile side trip to the northeast suburb of Hendersonville and Old Hickory Lake. We traveled to Hendersonville to visit the site of Twitty City (the former home and amusement park complex owned and operated by Conway Twitty in the 1980s and 90s), Marty Robbins’ recording studio that he never used (he died in 1982, the same year it was set to open), Johnny and June Carter Cash’s gravesites, and the Cash family home at 200 Caudill Drive in Hendersonville. Well, what was left of it anyway. As you might imagine, the Cash Home, often described as country music’s Graceland, has an interesting history.

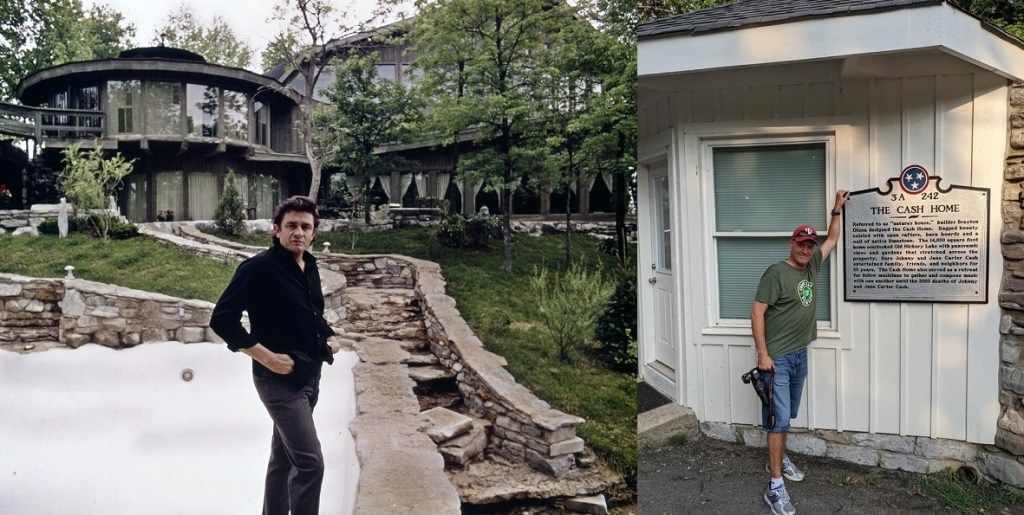

Johnny Cash fell in love with the house and the sprawling property the moment he saw it. Builder Braxton Dixon was building the home for his family, but Cash convinced him to sell it as a wedding present from Johnny to June. Dixon was no stranger to building celebrity homes, having built homes for Roy Orbison, Tammy Wynette, and Marty Stuart. Johnny bought the seven-bedroom/five full bathroom, 14,000 square foot mansion overlooking Old Hickory Lake in 1967 and lived there with June from 1968 to 2003. The four-lot lakefront property features five acres sitting right on the water, including 1,000 feet of lake frontage. The four large, 35-foot round front rooms featured stunning views of the property. Johnny and June lived there for 35 years and Cash wrote much of his famous music there. It was the only home the couple ever lived in together. Johnny Cash’s parents, Ray and Carrie, lived across the road from his mansion. Johnny’s brother Tommy described the house as “a very unusual contemporary structure. It was built on a solid rock foundation with native stone and wood and all kinds of unusual materials, from marble to old barn wood. I don’t think there was a major blueprint. I think the builder was building it the way he wanted it to look.”

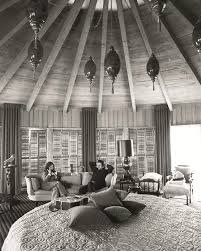

It was the spiritual home of Cash and the musical universe he created. The home was visited by nearly every famous country star you can imagine: actors, rock stars, artists, politicians (Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and Vice President Al Gore), and even Billy Graham. June cooked for them all in the home’s kitchen: eggs, pancakes, and ham in the morning, fried chicken, cornbread, and biscuits all day long. The home hosted Cash family Christmas celebrations, songwriting sessions, and informal jams (Johnny called them guitar pulls) featuring the likes of Bob Dylan, Brooks & Dunn, Joni Mitchell, Graham Nash, and a slew of others. In 1969, legend claims that an upstart songwriter named Kris Kristofferson landed a helicopter on the lawn, in hopes of getting the home’s famous owner to listen to some demos (from which Johnny picked “Sunday Morning Coming Down”). Cash’s late ’60s and early ’70s “guitar pulls” were held in a lakeside room accessed through a hallway and down some stairs from the home’s main family room. Although informal, these star-studded jams were profound, as Johnny writes in his 1997 autobiography, “Kris Kristofferson sang ‘Me and Bobby McGee’ for the first time … and Joni Mitchell’s ‘Both Sides Now.’ Graham Nash sang ‘Marrakesh Express’, Shel Silverstein’s ‘A Boy Named Sue’ and Bob Dylan let us hear ‘Lay Lady Lay” during those sessions.”

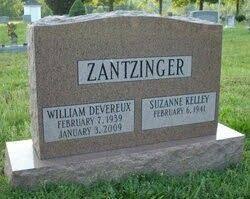

The couple lived happily in their lakefront home until their deaths four months apart in 2003. With Johnny at her bedside, June died on May 15, 2003, at the age of 73, following heart valve replacement surgery. Johnny Cash died on September 12, 2003, at the age of 71, from what doctors said were complications from diabetes, but most believe he died of a broken heart. They are buried at the Hendersonville Memory Gardens near their home. A visit to the cemetery finds the manicured plot of the Cash family, the polished bronze grave ledger of John R. Cash at the left, and June Carter Cash to the right. The markers lay flat against the earth, completely covering the bodies that rest below. The markers usually found peppered with coins and guitar picks, feature facsimile signatures of both artists along with Old Testament Bible quotes from the book of Psalms. June’s mother Maybelle Carter and her sisters Helen and Anita are buried nearby. As are Luther Perkins, the original guitarist of Cash’s “Tennessee Three” band, and country stars Ferlin Husky and Sheb Wooley rest nearby.

The Cash Mansion became an empty shrine to the duo for two years following their deaths. The couple’s furniture and many of their belongings, at least those that June didn’t give away to friends and family during the last years of her life, were still inside the house, but the couple was gone. It was always a tourist spot. Countless Greyhound buses, station wagons, vans, and carloads of people made the trek up that winding, narrow lane every day to lean on the stone and wood fence imagining Johnny and June as they were in life walking the property. To the surprise of many, in 2006, the Bee Gees’ Barry Gibb purchased the Cashes’ home for a mere $2.3 million. The Bee Gees frontman bought the property with plans of renovating, restoring, and making it an artist/writer’s retreat. Although he remodeled the interior, Gibb was determined to preserve the home to honor their memory and even pledged to keep intact whatever furnishings and decorator accents left behind. June was legendary for filling the house with ornate, tasteful objects that she had picked up and shipped home from performances all over the world. The renovations were at their final stage and Gibb was expected to move in that summer.

At 1:40 pm on April 10, 2007, a fire broke out outside the stone and wood building and while the fire department was on the scene within five minutes, the structure was already engulfed and the three-story contemporary structure burned to the ground. Only the chimney was still standing. But, a few original parts of the property survived the inferno, including the original garage, a covered boat dock, a bell garden, and a cute 1-bed, 1-bath detached apartment space where June stored her stage costumes. There’s also a tennis court, swimming pool, and a little guardhouse by the gate. The stone walls and steps that surrounded the home are still there as well as the stone/wood fences and gates that surround the property as they have done for half a century. The picturesque hardscaping still frames the trails that once hosted walks near the water from country royalty. The blaze spread quickly due to the flammable materials used in the construction work taking place in the mostly wooden interior. It was later revealed that the exterior structure itself was gutted when a flammable wood preserver that had been applied to the house caught on fire. Firefighters said the unusual multi-level structure of the house made the blaze even tougher to tackle. To his credit, Bee Gee Barry Gibb had removed most of that furniture, like Johnny and June’s bed, during renovation and it was safe and sound in storage.

While much music was written inside the mansion, not much music was made inside its walls. Photos of the Cash mansion can be found all over the internet and there are a couple of well-made videos you can check out too. The home was featured in the movie Walk the Line. In the film, the property is shown when Johnny and June’s families come together for Thanksgiving dinner. But the better view can be found in a 2002 music video filmed before Johnny died for the song “Hurt” which was filmed in the home. The video depicts a weakened, vulnerable Cash looking back at his life while surveying the home he and June shared. The video was largely filmed there, and it shows rare interiors of the home as well as views of the derelict House of Cash museum nearby. It is a must-see. Cash’s final recordings took place within the house as well, when he was too weak to make it to a studio.

If you visit the Cash property today, you can almost feel Johnny’s presence. After all, you can lean against Johnny’s stone & wood fence along Caudill Drive and gaze at the remaining buildings with ease. If you spend any time there, you’re likely to be joined by other pilgrims on the Cash trail. Not much in the way of conversation, just long moments of quiet reflection and an occasional nod of shared reverence. However, if you look over your left shoulder across the street, you can see the house where Johnny died. Johnny spent his final days living in the house at 185 Claudill Drive overlooking his old Lake House. The ranch house, which was built by the same architect, Braxton Dixon, was always referred to as “Mama Cash’s house” because it was where Cash’s parents lived before their passing. The ranch house is expansive, with 4 bedrooms, 3 bathrooms, vaulted ceilings, stone fencing, and 200 feet of road frontage. Johnny spent his last days there when it became harder for him to get around in a wheelchair in the lake house. Both the lake house property and ranch house across the street have been sold (or have been offered for sale) in the years since Cash’s passing. The issue remains unclear and when I reached out to the registered owners for this story a few years back, my e-mails and phone calls were never responded to, so…

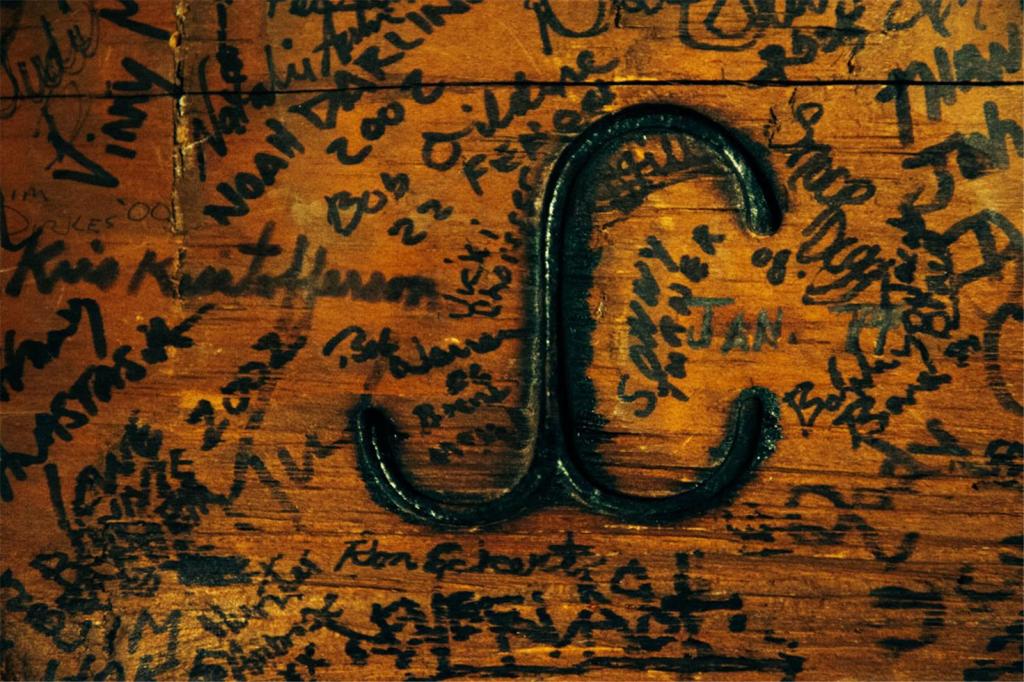

Better still, there is another lesser-known living connection to Johnny Cash on Caudill Drive. In 1978, Johnny began building a log cabin, finishing it in 1979. He intended to use it for rest, relaxation, songwriting, and recording. He named it Cash Cabin Studio but friends and family said the man in black called it the Sugarshack. The year the Cabin was built, Elvis Costello and Dave Edmunds along with members of the band Rockpile visited, being some of the first to write their names on the fireplace mantle piece. Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers stopped by in the early 1980’s. In 1982 Johnny’s daughter Kathy and her husband Jimmy were wed there. Television star John Schneider of “The Dukes of Hazard” fame lived in the cabin for some time in the mid-1980s. Other early visitors included actor Robert Duvall, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and Bono and Adam Clayton of U2.

According to the website, “In 1991, June’s sister Anita Carter moved into the cabin and made it her home. It was Anita who first recorded in the cabin. Recording gear was brought in and set up and featured some wonderful musicians including Anita’s dear, old friend and master producer/guitarist Chet Atkins. In 1992, Johnny met producer Rick Rubin. Rick had a diverse creative palate, having made recordings for Run DMC, The Beastie Boys, and several other groundbreaking rap and heavy metal artists. Johnny signed up with Rick’s record company and went to California to work with Rick. Although most of Johnny’s first album in the Grammy Award-winning American Recordings series was recorded at Rick’s Los Angeles home, there were a couple of tracks recorded in the Cabin, with a simple tape machine and standard microphones. The magic of the Cabin’s music took off from there. Johnny went on to record almost half of the remainder of the American Recordings series at the Cabin. June Carter Cash also recorded both of her latter life Grammy Award-winning albums Press On and Wildwood Flower at the Cabin. Through this process, John Carter Cash worked intensely with his parents on their music. In the Summer of 2003, Johnny’s last recording, made mere days before his death, was in the Cabin. He recorded two songs in their entirety in those two sessions that day: “Like the 309” early in the day, for the album “American Recordings V, A Hundred Highways”, and “Engine 143” at the end of the day, for an album being produced by John Carter, “The Unbroken Circle, The Musical Heritage of the Carter Family”. But the story doesn’t end there.

Next Week: Part 2 of Johnny and June Carter Cash’s Home: Nashville’s Graceland.

Johnny and June Carter Cash’s Home: Nashville’s Graceland, Part II.

https://weeklyview.net/2024/08/29/johnny-and-june-carter-cashs-home-nashvilles-graceland-part-2/

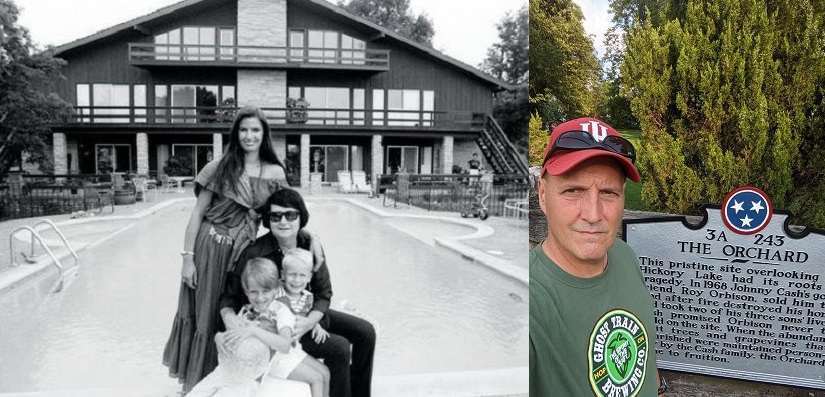

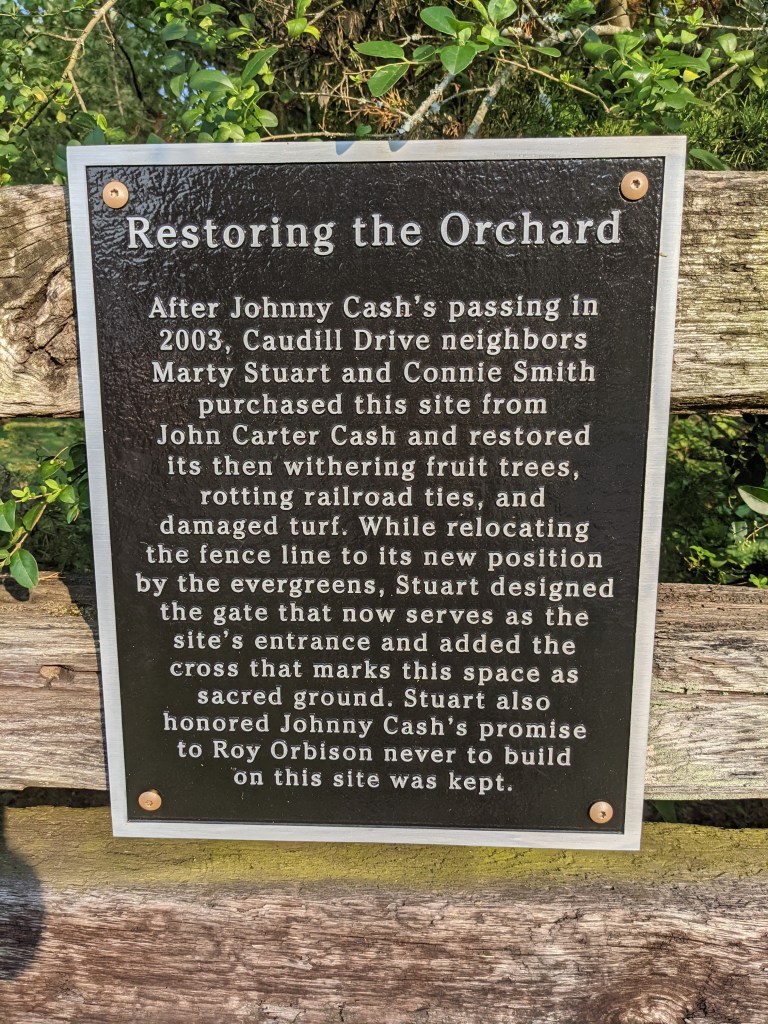

After reading Part 1 of this article, it should come as no surprise that Johnny and June Carter Cash’s beloved Lake House has a mystique all its own. Johnny and June lived happily in the house for some 35 years. When they died (four months apart) in 2003, it sat empty for two years before it was sold by the Cash’s son, John Carter Cash, to Barry Gibb of the Bee Gees. As a bevy of contractors worked to meet the Gibbs’ July 4 deadline, the home caught fire and burned to the ground on April 10, 2007. Then Gibbs built a new house on higher ground, keeping the original Cash home foundations as a testament to the memory of Cash. The new house has been sold a few times but the Cash property remains pretty much the same as it was after the fire. Johnny and June had some famous neighbors too: Marty Stuart (Cash’s former son-in-law) and The Oak Ridge Boys’ Richard Sterban among them. After the fire, Sterban reportedly remarked that “perhaps, after all, no one except Johnny and June Carter Cash were meant to live at the lake house.”

So the Cash presence is strong here. While the Johnny Cash story is complicated, Kris Kristofferson wrote of his friend “John” that “He’s a walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction.” Cash struggled mightily with addictions and the only thing that saved him from himself was June Carter Cash. I can appreciate that. All questions of the Cash Lake House’s demise being tied to the passing of Johnny and June Carter Cash aside, Hickory Lake is no stranger to tragedy in its own right. There is an air of mystery that haunts Old Hickory Lake and extends beyond the charred ruins of the Cash mansion. Roy Orbison once owned a home right next to the Lake House. It burned down, killing two of his three sons. Orbison (1936-1988), was best known for his distinctive, natural lyric baritone voice featuring a range from A2 to G4: higher than the standard baritone range on the high end and not as low on the low end. Orbison’s (a.k.a. The Big O) lyric baritone voice was sweeter and lighter than the average baritone, and he could sing faster songs with more vocal agility than an average baritone. Orbison chose complex compositions and dark emotional ballads conveyed a quiet, desperate vulnerability, which led to his “Lonesome Roy” reputation. (Believe me, Roy Orbison was no boy scout. He was famous for his carousing and womanizing on the road and his conquest numbers could match anyone from Elvis to Wilt Chamberlain, but THAT is another story.) Between 1960 and 1964, 22 of his songs were placed on the Billboard Top Forty, including “Only the Lonely,” “Crying,” and “Oh, Pretty Woman.” Orbison’s trademark stage performance was standing still and solitary, lit by a single spotlight, dressed in black clothes and dark sunglasses which only added an air of mystery to his persona.

While playing a show in Birmingham England on Saturday, September 14, 1968, Orbison received the news that his home in Hendersonville had burned down. This occurred less than two years after the death of his wife Claudette Frady Orbison in a motorcycle accident on June 6, 1966, at the age of 24. It was a tragedy that plunged Orbison so deep into grief that he couldn’t write songs for a year and a half. To make matters worse, Roy received news that his sons Roy Dewayne Orbison, Jr. (age 10) and Anthony King Orbison (age 6) died in the fire. Their baby brother Wesley (age 3) survived. Fire officials stated that the cause of the fire may have been an aerosol can, which possibly contained some kind of lacquer. It was speculated that the boys were playing with a lighter or matches and using the spray can as a makeshift flame thrower when furniture or curtains ignited. The fire spread so quickly that when the boy’s grandparents, Orbie Lee Orbison and Nadine Shultz, opened the door to the room, the resulting blast knocked them to the other side of the house. Even though firefighters responded quickly, the flames were too intense to save the two young boys. By the time Roy made it home, all that was left of the home was the chimney.

Roy moved in with his parents and became a recluse, refusing to see or talk to anyone. When Johnny Cash visited, he found Roy sitting in his room staring at a television with the sound off. Cash told him that he loved him and was there for him. Orbison said he did not know how to cope with his grief. After the fire, Orbison had to start all over again and he could never bear the thought of rebuilding a home on the property. Roy’s parents helped to raise Wesley while his father was on the road and in the studio. In December 1988 just as his star was on the rise again, Orbison spent the night visiting with Wesley, from whom he had been estranged. The two stayed up all night singing together and writing songs. The following day, Roy died of a sudden heart attack at the age of 52.

Eventually, Johnny Cash bought the lot, promising Orbison that he would never build on the site again and insisting “Only good shall grow on this land.” The Cash family planted fruit trees and cultivated an orchard where the Orbison house once stood. It was not unusual to see Johnny Cash, watering can in hand, tending to the saplings during the early years of the orchard. As the fruit trees and grapevines flourished, they were maintained personally by the Cash family and the orchard came to fruition. Several years after Roy’s death, Johnny saw Wesley standing in the orchard on the lot where his brothers died. Cash asked Wesley why he was there. Wesley replied that it comforted him. Together, they gathered fruit from the orchard that Wesley took with him. Soon afterward, John and June gifted the lot to Wesley, who maintains the orchard to this day. It is ironic that years later, like Orbison’s, Cash’s house burnt, leaving only the chimney.

Not only was Johnny’s 1963 song “Ring of Fire” a hit, staying at No. 1 on the country chart for seven weeks and declared the number one greatest country song of all time by Rolling Stone Magazine, it was written by his wife June Carter years before they were married. Tragically, fire remained an unfortunate theme in Cash’s circle. On Saturday, Aug. 3, 1968, his first “Tennessee Three” guitarist, Luther Perkins, fell asleep on the couch in his den with a lit cigarette in his hand. Luther’s home (at 94 Riverwood Drive) was just a little further down the road from Johnny’s. The accidental fire failed to burn the home but Luther suffered burns over half of his body and never regained consciousness. Two days later, he died at Vanderbilt Hospital of burns sustained in that fire. Perkins had bought the lakeside house just two months earlier and had spent the afternoon of the fire installing a television antenna on the roof. When his wife returned home from a poker party at a friend’s house that night, she found the house filled with smoke, and flames in the den and the kitchen, her husband unconscious on the floor. Perkins had called Cash the night of the fire and asked him to come over. Cash, thinking Perkins’ wife was there to take care of him, begged off. Later, Cash would rank Perkins’ death with that of his brother Jack in terms of the impact it made on his life. “Part of me died with Luther,” Johnny said.

Bandmate Marshall Grant, who along with Cash and Perkins, made up the original “Tennessee Three,” wrote in his autobiography I Was There When It Happened, said, “Luther apparently woke up, realized what was happening, and tried to escape, but he was overcome by dense smoke and couldn’t make it to a sliding glass door leading outside. The house itself never caught fire, but there was terrible smoke damage, the likes of which I’ve never seen. They told us at the hospital that if Luther had lived, the doctors probably would have had to amputate his hands, and I don’t think he could have lived with that.” Luther Perkins is buried only yards away from Johnny and June Carter Cash at the Hendersonville Memory Gardens. Bassist Marshall Grant died on August 7, 2011, at the age of 83, in Jonesboro, Arkansas while attending a festival to restore the childhood home of Johnny Cash.

But wait, there’s more. Cash’s longtime friend, Faron Young, known as the ” Hillbilly Heartthrob” for his chart-topping singles “Hello Walls” and “It’s Four in the Morning” has an eerie connection to the Cash property as well. In 1972, Young was famously arrested and charged with assault for spanking a girl in the audience at a concert in Clarksburg, West Virginia, after he claimed she spat on him. Young appeared before a justice of the peace and was fined $24, plus $11 in court costs. Afterward, Young’s life was plagued with bouts of depression and alcoholism. On the night of December 4, 1984, Young fired a pistol into the kitchen ceiling of his Harbor Island home. When he refused to seek help for his alcoholism, Young and his wife Hilda separated, sold their home, and bought individual houses. When asked at the divorce trial if he feared hurting someone by shooting holes into the ceiling, Young answered “Not whatsoever.” The couple divorced after 32 years of marriage in 1986.

Feeling abandoned by fans and the country music industry and in failing health (he was battling emphysema, and had undergone prostate surgery for cancer), Faron Young penned a suicide note specifically enumerating his health and the decline in his career, shot himself on December 9, 1996. Sadly, Faron didn’t die immediately. Hearing the shot, Young’s long time friend and bandmate, Ray Emmett, rushed into the room to find Faron lying in his bed, still alive. Young was rushed to Nashville’s Summit Medical Center where the next day, December 10, 1996, at 1:07 p.m., he died at the age of 64. Faron Young was cremated, and his ashes were spread by his family over Old Hickory Lake at the house of Johnny and June Cash. In a “Country Music Spotlight” interview with Willie Nelson (who wrote Young’s biggest hit “Hello Walls”), Cash said, “He (Faron) was one of my favorite people, he was one day older than me. He requested that his ashes be distributed on Old Hickory Lake and my property. So they came out there with his ashes…and the wind was blowing…So he’s everywhere, he’s all over my place, my yard, my house, my windows, in my sill, on my car, I turned on my windshield wipers the next day and there’s Faron. There he went, back and forth, back and forth, until he was all gone.” So, the next time you’re heading south, take a side trip to Hendersonville and venture over to 200 Caudill Drive, park your car on the side of the road, put your elbows on Johnny Cash’s fence, and dream.