Original publish date October 3, 2024. https://weeklyview.net/2024/10/03/a-gift-from-a-friend/

Rhonda and I strolled through Irvington last week to reconnect with some old friends. We visited Ethel Winslow, my long-suffering editor at the Weekly View, and then stopped in to see Jan and Michelle at the Magick Candle. From there we went down to see Dale Harkins at the Irving and then popped into Hampton Designs to check in with Adam. After that, we tried (in vain) to track down Dawn Briggs for a stop-and-chat, then traveled over to see Randy and Terri Patee for a 3-hour porch talk over a fine cigar. Why do I retrace our visit with you? Simply because I hope that anyone reading this article either is, or will, make a similar stroll through the Irvington neighborhood this Fall season and visit their old haunts as well.

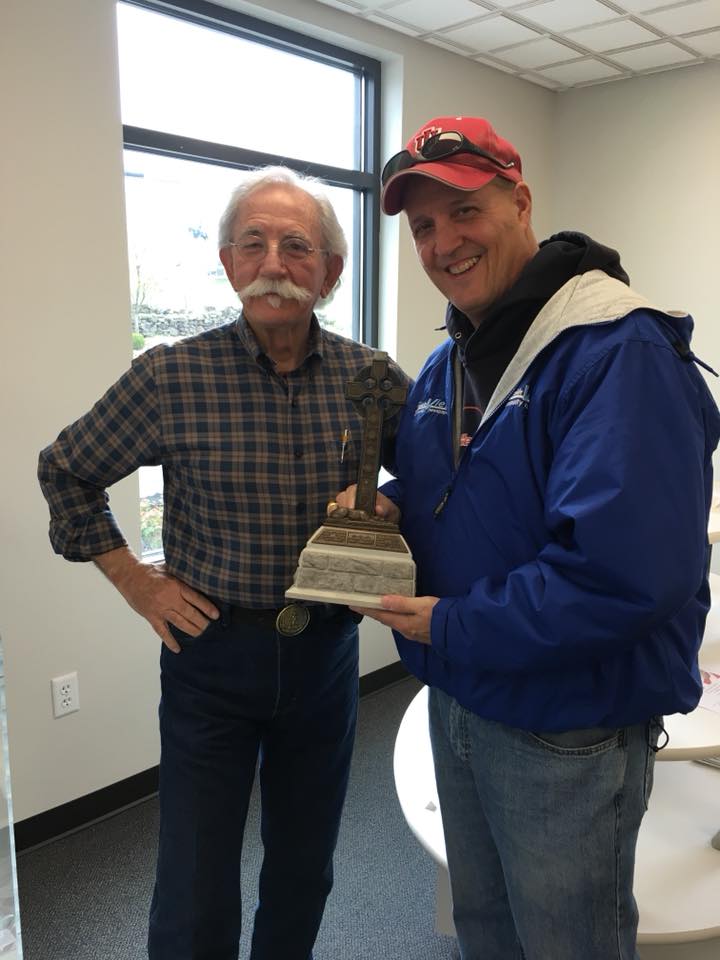

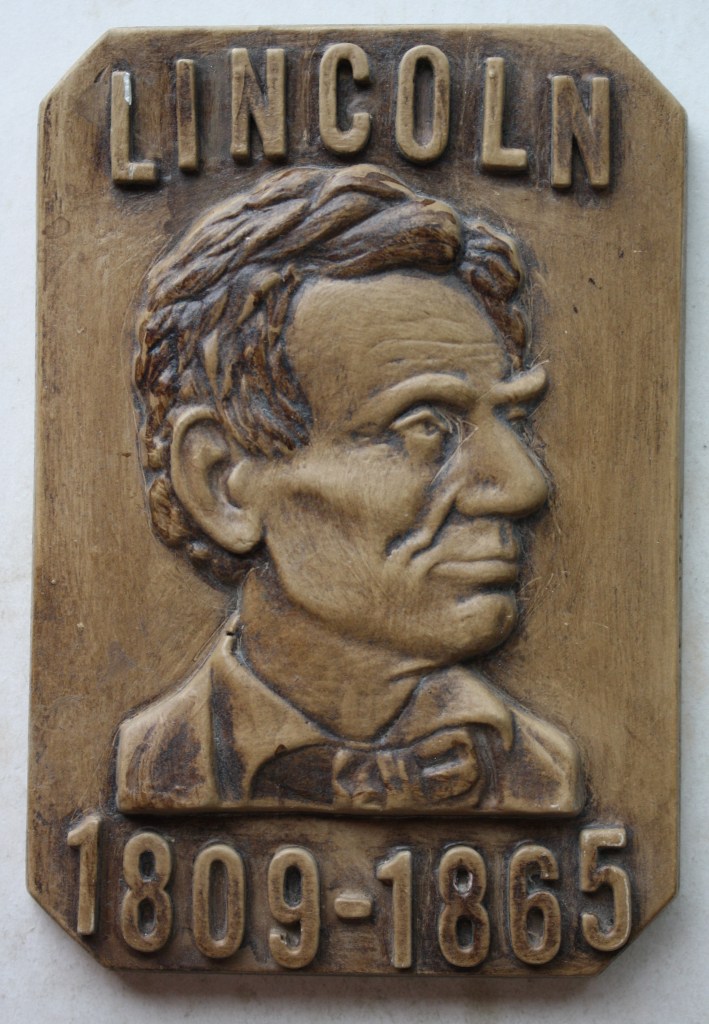

I am blessed to know these folks and every one of them has been kind, giving, and thoughtful to us over the years, particularly lately as Rhonda has faced some difficult health challenges. The gals at the Magick Candle have gifted me treasures over the years connected to the people and places they know I love (Disney’s Haunted Mansion and Abraham Lincoln come to mind), the Patees have given me relics from the pages of history, and yesterday, Adam stopped me in my tracks by stating, “Wait, Carter found something for you.” Adam fumbled around gracefully behind the counter before finding the object of his search. As he handed it to me, I felt certain that he believed it to be just another Lincoln item, but I knew immediately what it was.

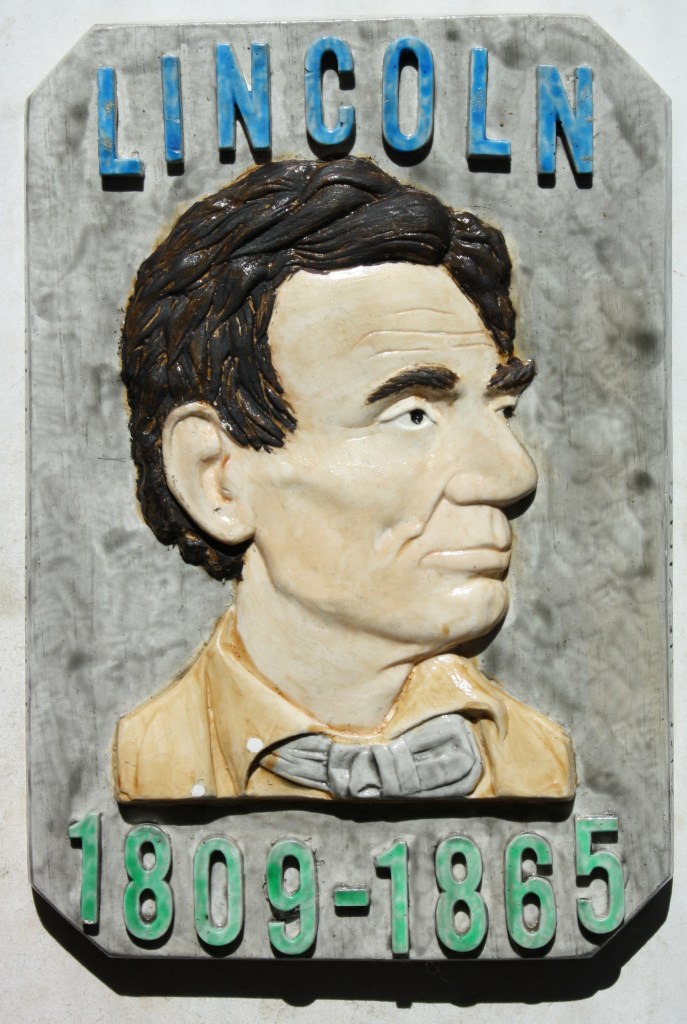

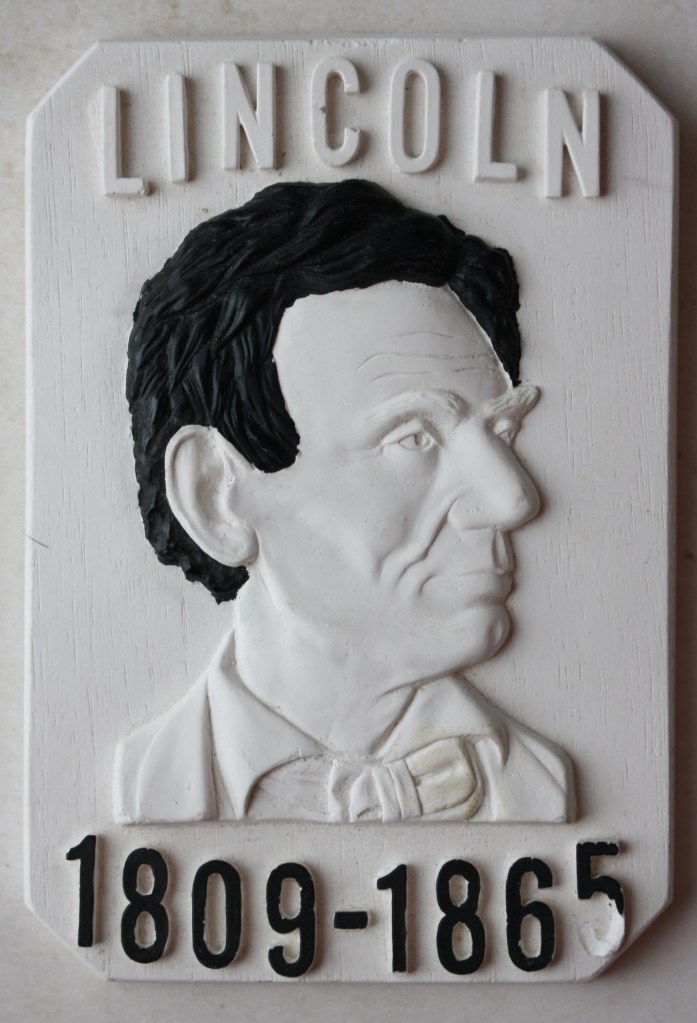

The object is a ceramic plaque about the size of a paperback novel picturing a young, beardless Abraham Lincoln with his birth and death dates inset in raised / relief lettering on the front. It is painted in bright Victorian Era colors that teeter on the edge of being gaudy but are always irresistibly attractive. Rhonda was standing by my side (as always) and when I showed it to her she oohed and aahed at it simply because she understands what such things mean to me. When I told her that it had a secret surprise attached to it, she looked closer at it. Knowing what was in store, I turned the plaque sideways in my hand to reveal the artist’s name, Art Sieving, on the right edge and then turned it over to the left edge to show the town name of Athens, Illinois. Since she has listened patiently to my historical ramblings for 35 years now, she wisely responded, “Oh, the Long Nine Museum.” Ding, ding, ding, we have a winner!

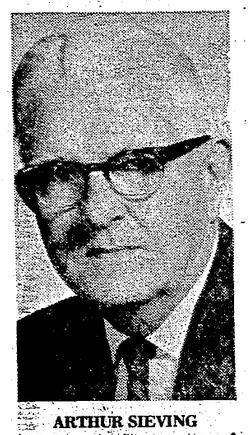

Carter and Adam had no idea, since, unlike me, they have lives outside of history books and museums, but with this gift, they had hit me in my sweet spot. I knew what it was because I already have a version, but mine, while still interesting to me, is a bland matte-finish version that pales in comparison to this one. These plaques were created by Arthur George Sieving (1902-1974) from Springfield, Ill. He was a wood carver, magician, sculptor, and ventriloquist who created many fine architectural carvings, clocks, and ventriloquist figures. At the time of his death, Art was working on the diorama displays at the Long Nine Museum in Athens. He is buried in Springfield’s Oak Ridge Cemetery final resting place of Abraham Lincoln. I was introduced, unknowingly, to Sieving’s work when, many years ago, I purchased a stunning metallic gold plaque depicting the Abraham Lincoln Tomb. About the size of a college diploma, like Carter’s plaque, it depicts the Tomb in a raised/relief style so realistically that it casts its own shadow depending on the lighting.

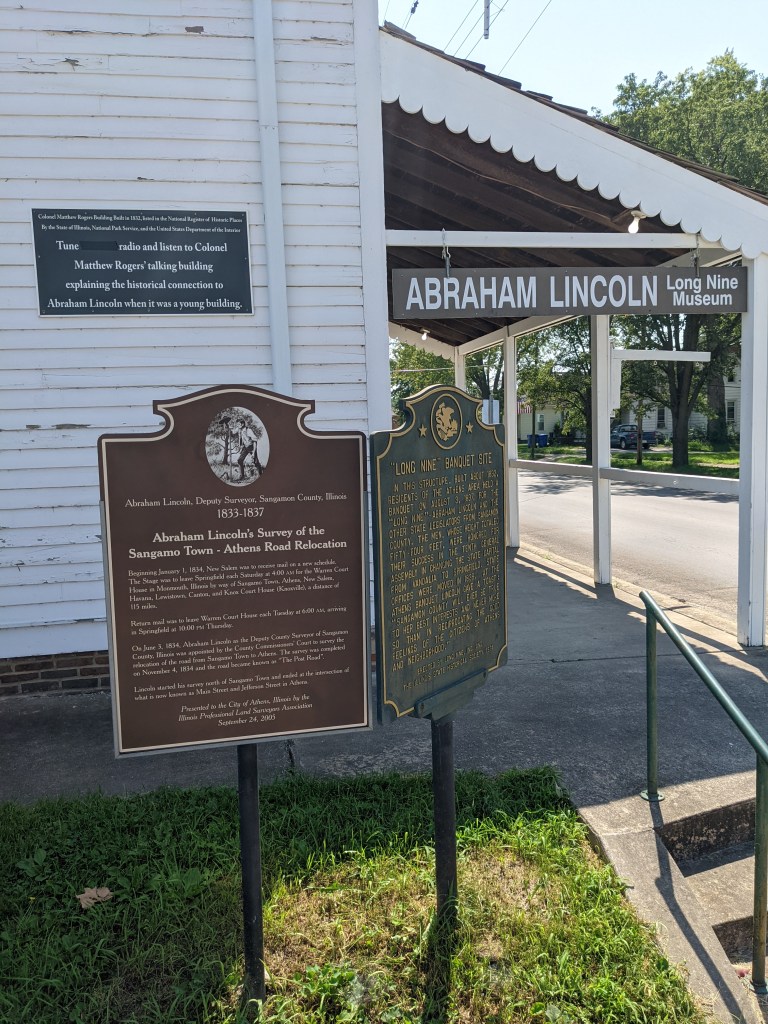

I had no idea who created the piece until I traveled to Athens (Pronounced Ay-thens) just a stone’s throw north of Springfield. I ventured there to meet with Jim Siberell, curator of the Long Nine Museum, who travels from his home in Portsmouth, Ohio during the summertime months to keep the museum open. Jim and I share a mentor in Dr. Wayne C. “Doc” Temple, the subject of my upcoming biography. As Mr. Siberell toured me through the museum, I spotted the exact plaque on display there. Of course, I asked for the history and Jim explained the artist’s connection to the museum. For those of you unaware, the Long Nine building is an important waymark of Illinois history. It was in this building, on the second floor, where Abraham Lincoln and six other state legislators (two of the members did not attend) decided to move the Illinois state capitol from Vandalia (near St. Louis) to the more centralized location of Springfield.

In 1837, a dinner party was held in the banquet room on the second floor to honor those legislators who were effective in passing a bill to relocate the capital. They earned the sobriquet of “The Long Nine” because together their height totaled 54 feet, each man being over 6′ tall or taller. Among the attendees was Abraham Lincoln, who at age twenty-seven was the youngest of the group. Lincoln gave the evening’s toast by saying, “Sangamon County will ever be true to her best interest and never more so than in reciprocating the good feeling of the citizens of Athens and neighborhood.” What this Hoosier finds most interesting is that when the delegates carved out the boundaries of Sangamon County, the home of the new state capitol, they left Athens out. Athens became a part of Menard County as did their neighbor, Lincoln’s New Salem.

Mr. Siberell toured me through the building and explained how Art Seiving had created the dioramas in the museum that recounted the stories of the men of The Long Nine in hand-carved wooden miniature displays. Each diorama’s characters were created by Seiving and the backgrounds were painted by artist, Lloyd Ostendorf. Siberell escorted me up the original stairway to the second-floor banquet room which features a stunning, massive oil painting by the late artist Lloyd Ostendorf showing Lincoln in formal dress toasting his colleagues. The mural covers an entire wall and is set against a table arranged much the same as it would have been on that fateful night. The visitor stands upon the original flooring of the banquet room where Lincoln gave his famous toast. The history room downstairs is a researcher’s dream. It contains many copies of Lincoln’s handwritten letters, documents from the history and restoration of the building, newspapers from the era, and historic photos. A trip to the basement reveals the building’s original fireplace, an arrray of period artifacts, and a scale model of Lincoln’s Tomb so big that it required the construction of a special pit to accommodate its massive size.

The March 23, 1973, Jacksonville (Illinois) Journal Courier reported. “Seiving has been working hard since January making the “Lincoln Head” plaques in his basement. He used a rubber mold taken from a carving…he pours into it the powdered molding material and fashions a Lincoln head of great exactness and beauty. During the past weeks, he has made enough of them to fill every available space in his basement. When he makes a few hundred more they will be delivered to a central point for use in Athens; he will then start on larger statues. The plaques being furnished are in white plaster material, but will be finished into a walnut appearance with a high polish and most attractive “feel” and “look”.

The article continues, “The classic dioramas made by Art Seiving will present all of those documented events which presented Lincoln in Athens, including hand-carved wooden figures, utensils, tools, buildings, and animals carved from wood.” One of Art’s carvings was titled, “Lincoln goes to school in Indiana”…It takes two people (himself and his wife) three nights to cut out 800 little paper leaves, and it’s no short job, either, to glue them to the branches, one by one. Others have taken longer. Mr. Seiving was five or six days just putting in 3,000 “tufts” of grass in his last completed scene. The grass is frayed rope strands, cut and dried and then glued down…And while you’d swear that the miniature pots and pans were made of metal, in actuality, most are simply wrapping paper glued to metal rings.” Sieving stated that it took him five to seven days to carve each figure, and one diorama alone featured 11 figures. His preferred medium was walnut with augmentations of birch wood.

Seiving is described as an “internationally known magician, sculptor and ventriloquist” whose “dummy” partner was known as “Harry O’Shea.” Of course, Art carved all of the ventriloquist dummies used in his acts himself. Art’s magic act was called the “Art Seiving and his Art of Deceiving.” Aside from the Long Nine Museum, he is best known for his dioramas at the Illinois State Museum, ‘Model of New Salem Village’ and wood sculptures including the ‘Egyptian Motif Clock’. Seiving’s George Washington carving is in the Smithsonian Institution’s collection.

Art’s Lincoln plaques are by no means rare but cannot be classified as common in the “collectorsphere”. I believe the Long Nine Museum still has a few for sale if memory serves, and one would set you back about the cost of a Starbucks coffee nowadays. To me, the value is not a monetary one, but rather the story the item tells. The version that Carter discovered (and so kindly gifted to me) is signed “Love, Laurie” on the back, making it all the more special to me. I tend to love these little travel souvenirs from the 1960-70s. I’m a space race Bicentennial kid who enjoys discovering these little treasures. They represent a vacation, a trip, a moment in someone’s life. Usually a kid, they are never confined to age, race, or gender. I appreciate that, in this age where everything handmade seems to come from China, most of these old travel souvenirs originate from where they were being sold. At that moment, they were the most important thing in that person’s life. Hand-picked with a smile and a “wow” to be taken home and enjoyed long after the trip concluded. A physical manifestation of a cherished memory. So thank you “Laurie” whomever or wherever you are for saving this little treasure for a history nerd like me. And most importantly, thank you Carter for thinking of me.

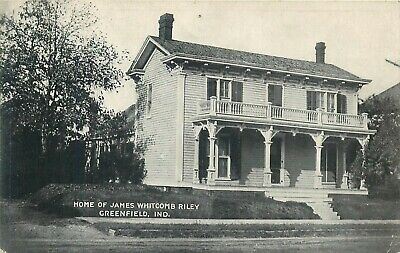

Although Lincoln and Riley died a half-century apart, the men had much in common. The two were considered the state’s most famous Hoosiers (that is until John Dillinger died in 1934) and their names were often linked in speeches, newspaper articles, books and periodicals in the first fifty years of the 20th century. One of my favorite quotes found while searching the virtual stacks of old newspapers comes from the July 20, 1941 Manhattan Kansas Morning Chronicle: “If you want to succeed in life, you might run a better chance if you live in a house with green shutters. Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain and James Whitcomb Riley all lived in such houses.” Lincoln and Riley epitomized everything that was good about being a Hoosier, right down to the color of their green window shutters.

Although Lincoln and Riley died a half-century apart, the men had much in common. The two were considered the state’s most famous Hoosiers (that is until John Dillinger died in 1934) and their names were often linked in speeches, newspaper articles, books and periodicals in the first fifty years of the 20th century. One of my favorite quotes found while searching the virtual stacks of old newspapers comes from the July 20, 1941 Manhattan Kansas Morning Chronicle: “If you want to succeed in life, you might run a better chance if you live in a house with green shutters. Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain and James Whitcomb Riley all lived in such houses.” Lincoln and Riley epitomized everything that was good about being a Hoosier, right down to the color of their green window shutters.

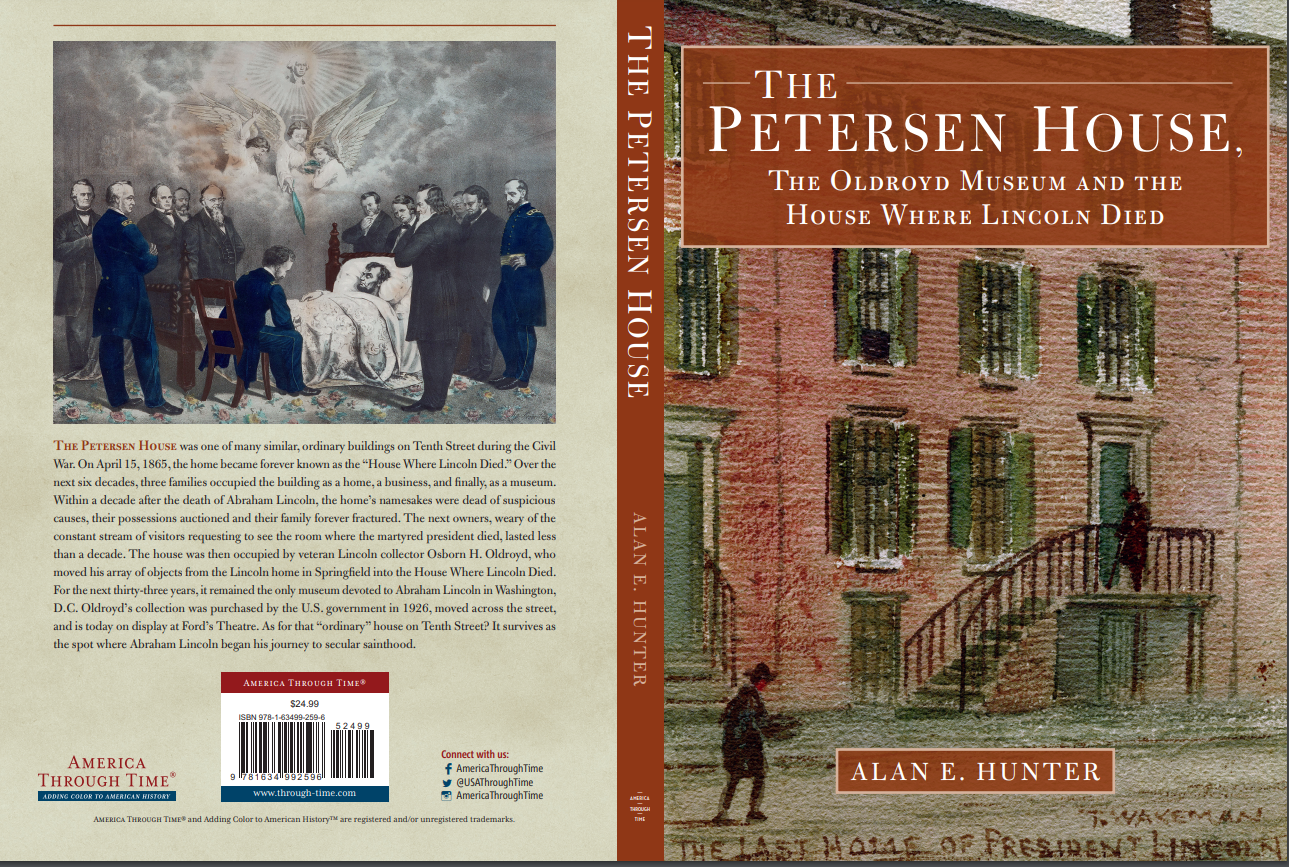

Oldroyd, a thrice-wounded Civil War veteran, collector, curator and author, is perhaps the father of the house museum in America. One of Oldroyd’s books, a compilation of poems entitled, “The Poets’ Lincoln— Tributes In Verse To The Martyred President”, was published in 1915. James Whitcomb Riley’s poem, A Peaceful Life with the name “Lincoln” in parenthesis as a sub-title can be found there on page 31. In Oldroyd’s version, the first line differs from Riley’s original version. Riley’s handwritten original (found today in the archives of the Lilly Library on the Bloomington campus of Indiana University) begins: “Peaceful Life:-toil, duty, rest-“. Oldroyd’s book version begins; “A peaceful life —just toil and rest—.” Interestingly, the Oldroyd version has become the standard. And there you have it. Oldroyd’s influence is subtle, his name largely unknown, yet he stays with us to this day.

Oldroyd, a thrice-wounded Civil War veteran, collector, curator and author, is perhaps the father of the house museum in America. One of Oldroyd’s books, a compilation of poems entitled, “The Poets’ Lincoln— Tributes In Verse To The Martyred President”, was published in 1915. James Whitcomb Riley’s poem, A Peaceful Life with the name “Lincoln” in parenthesis as a sub-title can be found there on page 31. In Oldroyd’s version, the first line differs from Riley’s original version. Riley’s handwritten original (found today in the archives of the Lilly Library on the Bloomington campus of Indiana University) begins: “Peaceful Life:-toil, duty, rest-“. Oldroyd’s book version begins; “A peaceful life —just toil and rest—.” Interestingly, the Oldroyd version has become the standard. And there you have it. Oldroyd’s influence is subtle, his name largely unknown, yet he stays with us to this day.

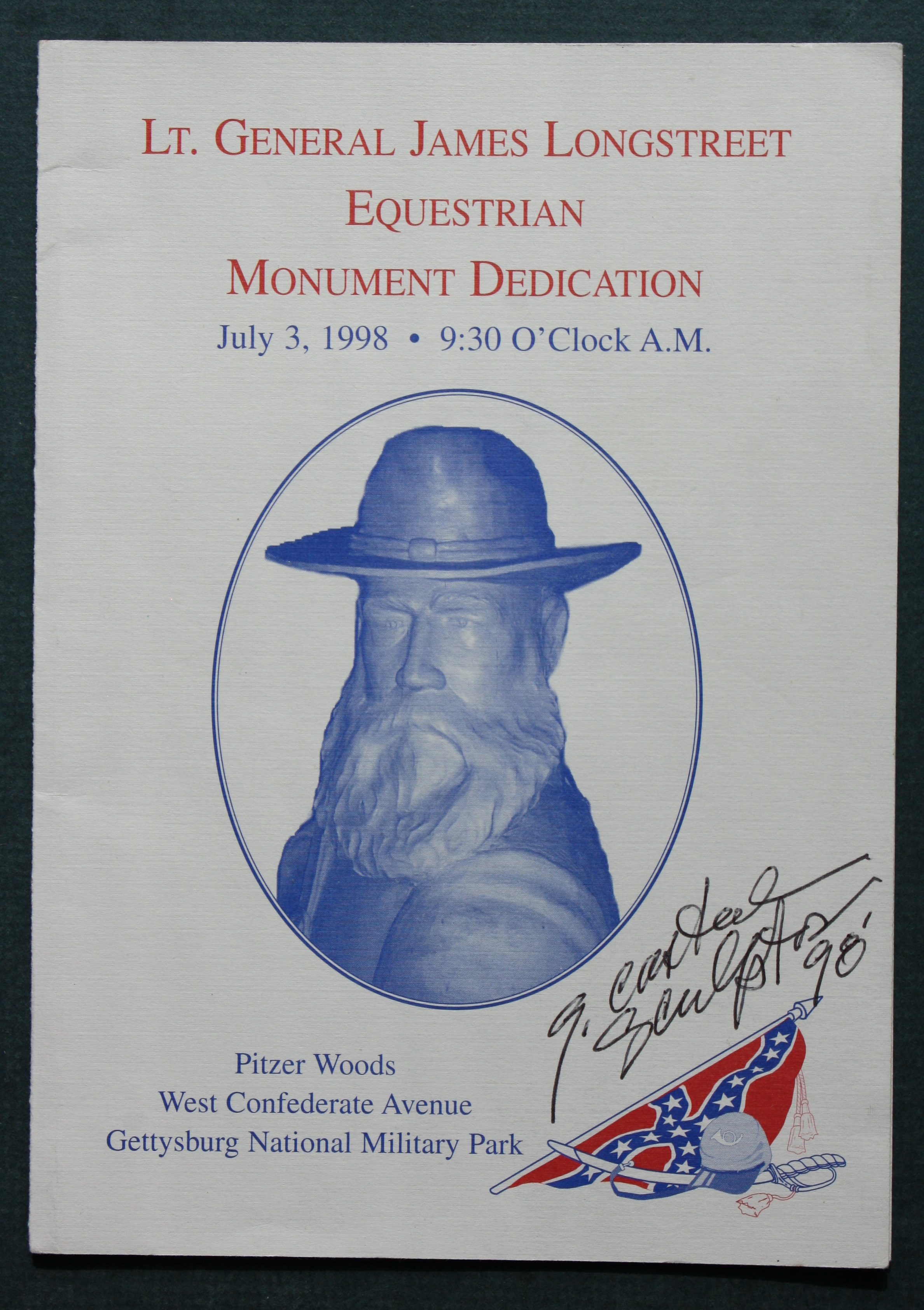

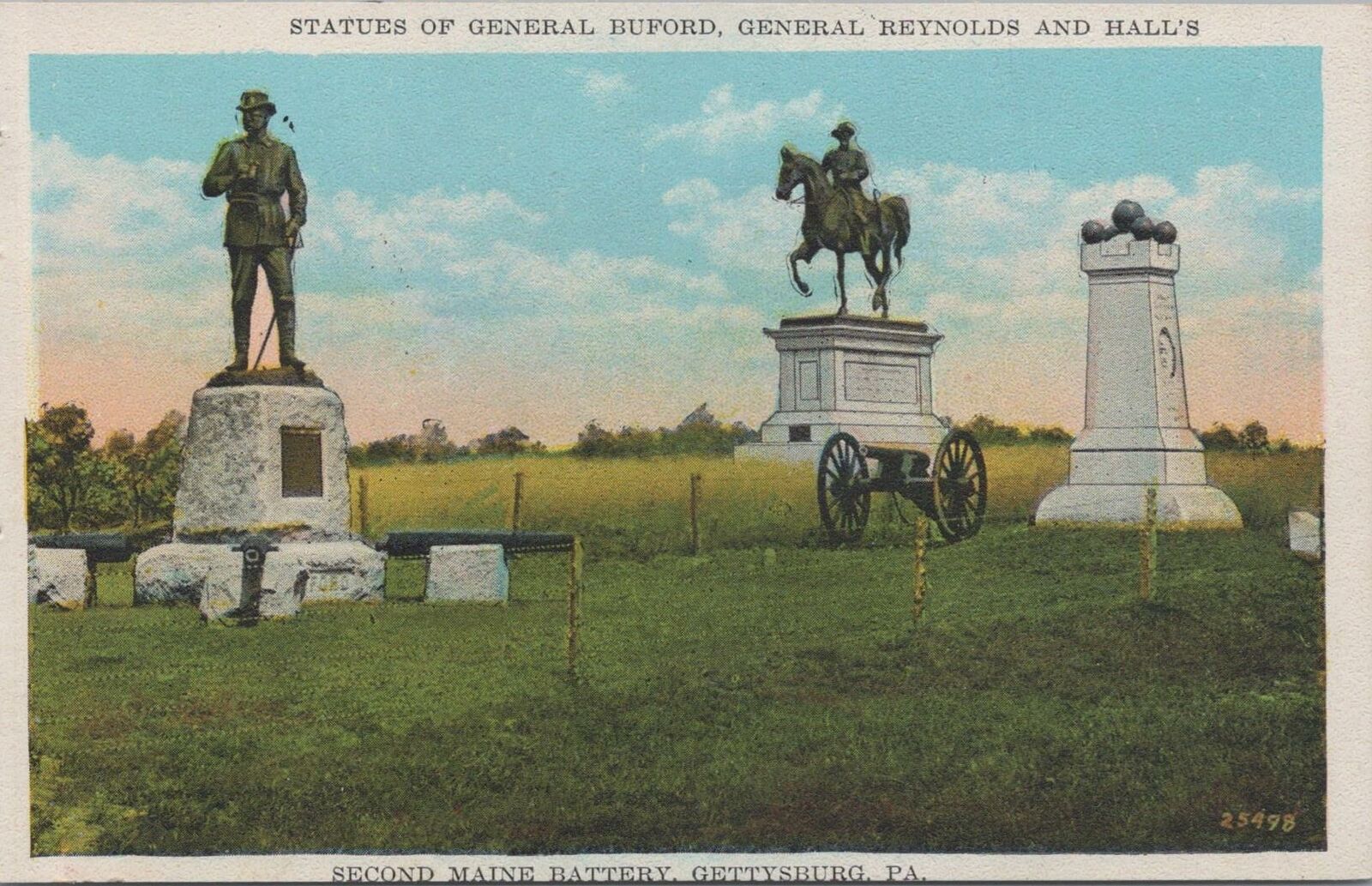

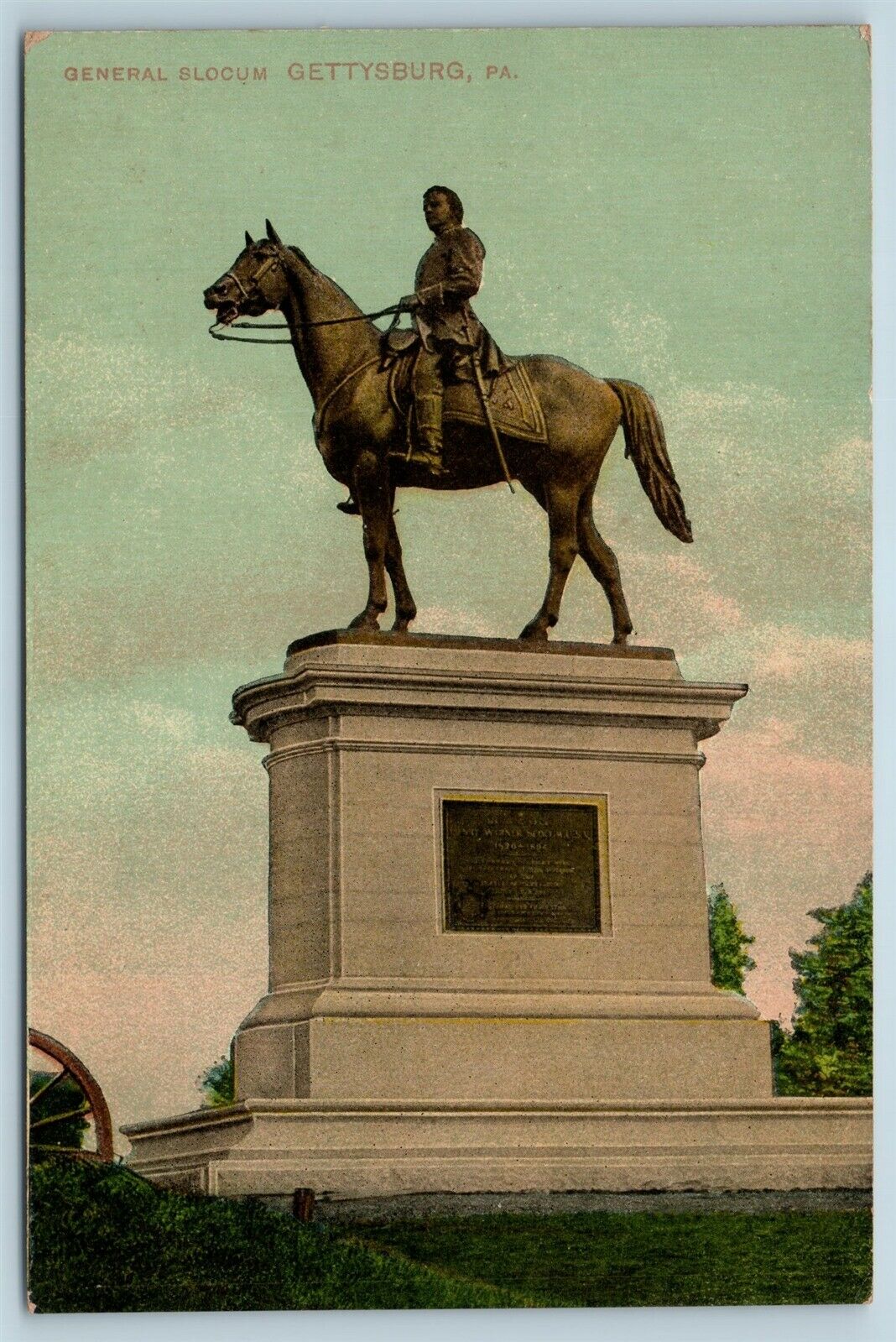

The statues on the field represent Union Generals Meade, Reynolds, Hancock, Howard, Slocum, and Sedgwick, and Confederates, Lee, atop the Virginia Memorial, and James Longstreet. According to the NPS, “Meade and Hancock were the first on June 5, 1896. They were followed by Reynolds, July 1, 1899, Slocum, September 19, 1902, Sedgwick, June 19, 1913, and Howard, November 12, 1932. The Virginia Memorial was dedicated on June 8, 1917. Longstreet did not come along until 1998 and by this time the myth was firmly established.”

The statues on the field represent Union Generals Meade, Reynolds, Hancock, Howard, Slocum, and Sedgwick, and Confederates, Lee, atop the Virginia Memorial, and James Longstreet. According to the NPS, “Meade and Hancock were the first on June 5, 1896. They were followed by Reynolds, July 1, 1899, Slocum, September 19, 1902, Sedgwick, June 19, 1913, and Howard, November 12, 1932. The Virginia Memorial was dedicated on June 8, 1917. Longstreet did not come along until 1998 and by this time the myth was firmly established.” But Hancock’s horse at Gettysburg? No one knows. Likewise, General O.O. Howard’s horse remains nameless (he had at least two shot out from under him and himself was wounded twice in battle) but the sternly pious one-armed General’s nickname of “Uh Oh” survives. So named by soldiers because when the General showed up, one way or another, there was gonna be a fight (he was awarded the Medal of Honor for actions at Gettysburg). Look up at his statue the next time you’re walking the field and you’ll see the empty flap of his right arm (shot off at the Battle of Seven Pines a year earlier) pinned neatly to his coat.

But Hancock’s horse at Gettysburg? No one knows. Likewise, General O.O. Howard’s horse remains nameless (he had at least two shot out from under him and himself was wounded twice in battle) but the sternly pious one-armed General’s nickname of “Uh Oh” survives. So named by soldiers because when the General showed up, one way or another, there was gonna be a fight (he was awarded the Medal of Honor for actions at Gettysburg). Look up at his statue the next time you’re walking the field and you’ll see the empty flap of his right arm (shot off at the Battle of Seven Pines a year earlier) pinned neatly to his coat.