Original publish date: April 4, 2019

So you say you have a scratchy throat? Runny nose? Nagging cough? Blaming all those hugs, handshakes and office hours for catching a bug? Well here’s a reminder that it could be worse. This reminder reaches all the way back to the Civil War and comes with a twist that extends to the present day.

Private Willis V. Meadors (erroneously identified as W.V. Meadows for decades) was a Confederate Veteran who served alongside his brothers and cousins in Company G of the 37th Alabama Volunteer Infantry. The 37th was involved in nearly every campaign of the western theater of the war between the states. Meadors was a sharpshooter with the Rebel army commanded by Lt. General John C. Pemberton posted at Vicksburg, the last major Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. General Ulysses S. Grant’s army had besieged the city since May 25.

It was July 1st, 1863, the day before the pivitol battle of Gettysburg commenced. After holding out for more than forty days, with no reinforcements and supplies nearly gone, things were getting desperate. While languishing in the trenches, Pvt. Meadors cobbled together a shield made of pig-iron. His crudely constructed armored bulwark had one hole to see through and another to fire his weapon. The shield worked well at first, allowing the Rebel sharpshooter to fire with impunity and relative security. Then, like a scene from a Hollywood movie, as the sharpshooter lined up his next shot, he was shot in the eye through his very own peephole. Miraculously, he survived.

It was July 1st, 1863, the day before the pivitol battle of Gettysburg commenced. After holding out for more than forty days, with no reinforcements and supplies nearly gone, things were getting desperate. While languishing in the trenches, Pvt. Meadors cobbled together a shield made of pig-iron. His crudely constructed armored bulwark had one hole to see through and another to fire his weapon. The shield worked well at first, allowing the Rebel sharpshooter to fire with impunity and relative security. Then, like a scene from a Hollywood movie, as the sharpshooter lined up his next shot, he was shot in the eye through his very own peephole. Miraculously, he survived.

Meadors was found and brought to a field hospital where Union surgeons probed for the bullet, but were unable to locate it. The bullet was resting perilously close to the soldier’s brain and the doctors didn’t feel it was safe to perform an operation. He was put aboard a POW ship and transported to a Union hospital. Later, he was paroled to a Confederate hospital, where he spent the rest of the war. In time, Meadors recoved well enough to serve as an aide at the Rebel hospital. His official medical records confirm that he’d been “severely wounded” in the head by a minie ball.

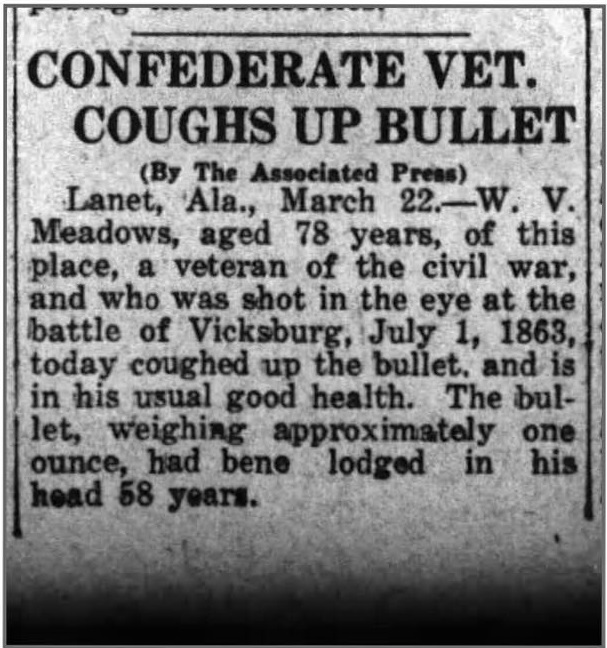

After the war, Meadors returned to his farm in Lanett, Ala., just east of the Georgia state line. The bullet cost Meadors his right eye and would remain lodged in his head for the next 57 years. He married, but had no children. He probably would have died in obscurity had it not been for a coughing fit in March of 1920. 78-year-old Willis Meadows had been steadily coughing all day long. His coughs soon turned to violent spasms. To Meadors, it felt like something was caught in his throat. Finally, with one great whoop, that something flew out of Meadors’ mouth and landed with a clatter on the floor a few feet away. It was the one-ounce bullet, trapped in Meadors’ head for over two generations.

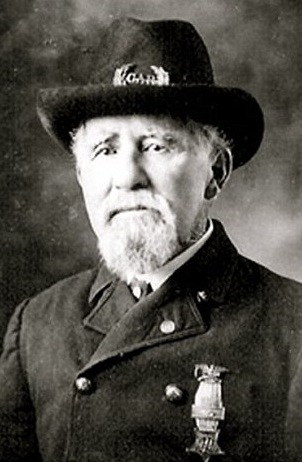

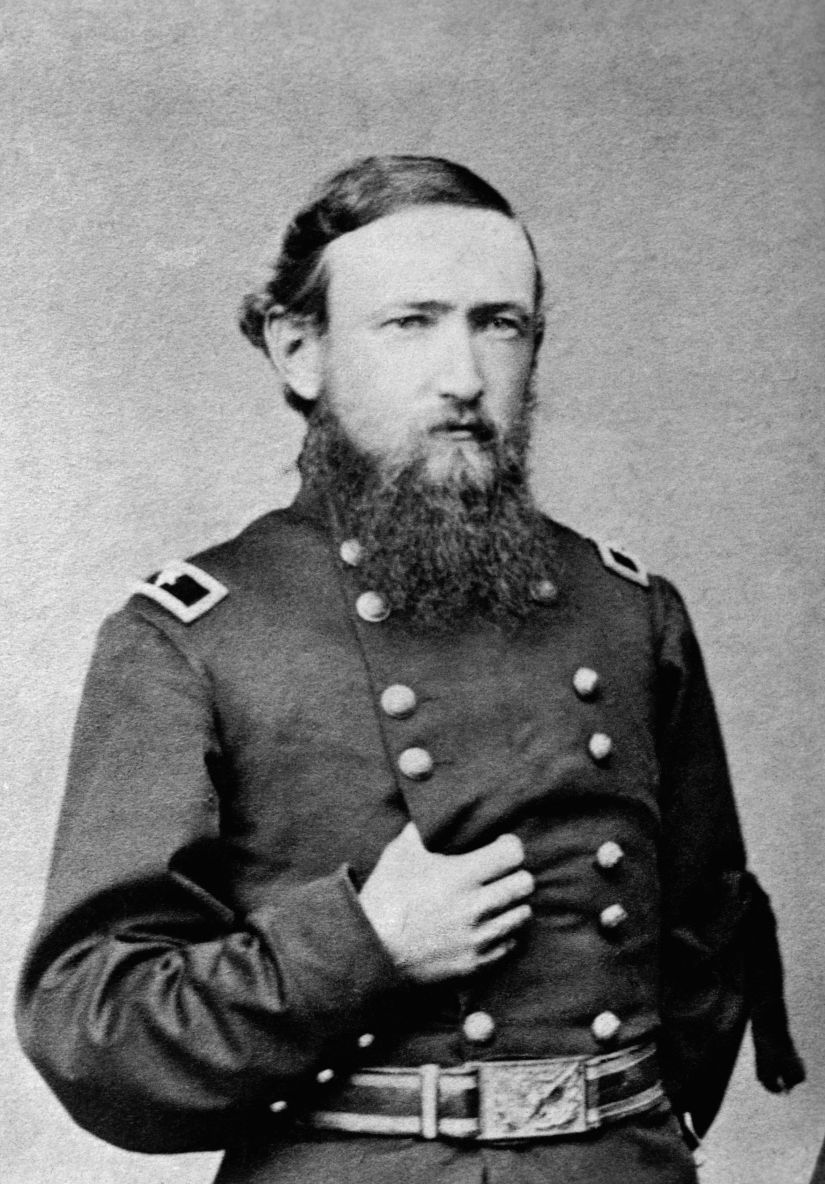

Instantly, the “Coughs Up Bullet” story became headline news. It ran in every major newspaper in the U.S. When the story made it into Ripley’s Believe It or Not, Meador’s story got even more unbelievable. Union veteran Peter Jones Knapp, who served at Vicksburg and Shiloh, saw the story and realized he was the one who fired the bullet that lodged near Meadors’ brain. In 1863, 21-year-old Knapp was serving with the 5th Iowa Volunteer Infantry. On July 1st, Knapp and three other Union soldiers of his Company were approaching from the east with specific orders to kill Confederate snipers. Knapp spotted Meadors, aimed his rifle at the boiler plate peephole and fired. Meadors fell to the side, blood running from his right eye. Knapp was sure his man was dead and the trio moved on.

Knapp was captured a few months later at the Battle of Missionary Ridge and was held in a number of Confederate prisons, including the notorious Andersonville in Southern Georgia, where almost 13,000 Union soldiers died. After the war, he farmed in Michigan, married, and in 1887, moved to Kelso, Washington. Knapp contacted Meadors and when the two old soldiers compared notes, they made the connection. Once mortal enemies sworn to kill each other, now, the aging veterans would spend their last few years as friends, exchanging letters, photographs and wishing each other good health.

Willis V. Meadors died at his home on October 10, 1927. His obituary stated that his health had been exceptionally good until the past few months except for a cancer on his face, which caused his death. He is buried at Oakwood Cemetery in Lanett, Alabama. Peter Knapp, the man who’d made that incredible shot at Vicksburg so many years before, preceded his target in death on April 13, 1924. His obituary states he died peacefully in the arms of his wife on April 13, 1924. His remains were sent to the Old Portland Crematorium. When Knapp’s wife Georgianna died in 1930, her remains also were cremated in Portland and placed next to those of her husband.

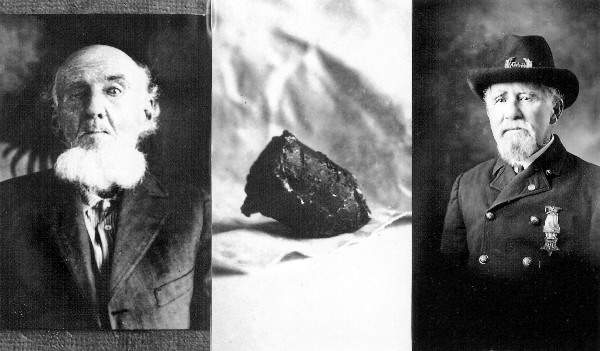

You’d think, that was the end of this fascinating story. But it turns out that in 1990, the story takes an even more bizarre turn. A man named Henry Kilburn was doing some genealogy research. Mr. Kilburn has the personal diary of Peter Knapp. Kilburn circulates a photograph of the coughed-up bullet flanked by photographs of Willis Meadows and Peter Knapp, which rekindles interest in the story. Kilburn admits that he is no blood relative of Peter Knapp, which prompts the question, how did Henry Kilburn end up with those items?

Turns out, Peter Knapp and his wife, who were childless, adopted Henry Kilburn’s younger sister, Minnie Mae. Their mother had been divorced and abandoned by her husband. She must have decided that adoption by the Knapps would provide her daughter with a better life. It was Mae who gave the items to Henry. The story fades from the pages of history once again for another generation. In 2012, Alice Knapp, the wife of the 3rd great nephew of Peter Knapp is researching the Knapp family history. In particular, she was searching for the burial site of Peter and Georgianna Knapp. She finds an obituary for Peter stating he had been cremated but it made no ,mention of the final resting place. Fortunately, the Old Portland Crematorium is still in business as Wilhelm’s Funeral Home in Portland, Washington.

Alice contacted the crematorium and was told no one had ever claimed the cremains of Mr. & Mrs. Knapp. She was told that the couple’s ashes were still on a shelf in the back room where they had been resting for decades. Astonished at the news, she then made contact with the Oregon Military Department of Veteran’s Affairs. She reasoned that because Peter Knapp was a Veteran of the U.S. Army he deserved a military funeral. On April 13, 2012 he got it.

Peter Knapp was laid to rest in Willamette National Cemetery, the first Civil War veteran to be buried in Oregon’s largest military graveyard. Knapp received full military honors from the Oregon National Guard 88 years to the day of his 1924 death. The funeral also fell on the 151st anniversary of the Confederate victory at Fort Sumter, S.C., which ignited the Civil War.

The burial attracted a mix of veterans, historians, Civil War re-enactors and people who were simply curious. Eras collided as cellphone and digital cameras recorded men and women dressed as Union soldiers and civilians marching alongside Patriot Riders holding 50-star American flags perched on shiny Harley Davidson motorcycles. The hearse carrying the twin gold boxes containing the ashes led the procession. The speakers largely focused on what Peter Knapp endured as a soldier, his incredible reunion with the man he shot and his commitment to his wife of more than 53 years.

The Sons of the Union Veterans of the Civil War performed a ritual for the dead based on a Grand Army of the Republic ceremony from 1873. The funeral also included a bagpiper playing “Amazing Grace,” a bugler who performed “Taps,” and culminated with the laying of wreaths. Following a musket salute, a folded U.S. flag was presented to Alice Knapp. And, despite his connection to one of the strangest incidents of the Civil War, there was not a Confederate in sight.

The first order of business was to hide the fact from Devin’s widowed mother until the body could be recovered, and the second was to take precautions for safeguarding John Scott Harrison’s remains. Benjamin Harrison and his younger brother John carefully supervised the lowering of his father’s body into an eight-foot-long grave. At the bottom, they placed the state-of-the-art metallic casket into a secure brick vault with thick walls and a solid stone bottom. Three flat stones, eight or more inches thick were procured for a cover. With great difficulty the stones were lowered over the casket, the largest at the upper end and the two smaller slabs crosswise at the foot. All three of these slabs were carefully cemented together. The brothers waited patiently beside the open hole for several hours as the cement dried. Finally, with their father’s remains still under guard, a massive amount of dirt was shoveled into the hole and the brothers departed secure in the notion that their father would rest in peace for all eternity.

The first order of business was to hide the fact from Devin’s widowed mother until the body could be recovered, and the second was to take precautions for safeguarding John Scott Harrison’s remains. Benjamin Harrison and his younger brother John carefully supervised the lowering of his father’s body into an eight-foot-long grave. At the bottom, they placed the state-of-the-art metallic casket into a secure brick vault with thick walls and a solid stone bottom. Three flat stones, eight or more inches thick were procured for a cover. With great difficulty the stones were lowered over the casket, the largest at the upper end and the two smaller slabs crosswise at the foot. All three of these slabs were carefully cemented together. The brothers waited patiently beside the open hole for several hours as the cement dried. Finally, with their father’s remains still under guard, a massive amount of dirt was shoveled into the hole and the brothers departed secure in the notion that their father would rest in peace for all eternity. John Harrison shrugged off the discovery knowing that his cousin Augustus Devin, the subject of their search, was a very young man. Still, the body was lain flat on the floor and the cloth was cast aside with the aid of a nearby stick. As the dead man’s face was revealed, John Harrison gasped in horror that the dead body was none other than that of his father, John Scott Harrison.

John Harrison shrugged off the discovery knowing that his cousin Augustus Devin, the subject of their search, was a very young man. Still, the body was lain flat on the floor and the cloth was cast aside with the aid of a nearby stick. As the dead man’s face was revealed, John Harrison gasped in horror that the dead body was none other than that of his father, John Scott Harrison.

is a rope with a hook at one end, a short crowbar, and a spade and a pick. He generally has a “pard,” as it is easier to hunt in couples. He is notified of the “plant” (body), and by personal inspection makes himself familiar with all the surroundings, before the attempt is made. The pick and spade remove the earth from the grave as far as the widest part of the coffin, and with the crowbar, the coffin is shattered, and the rope with the hook end fastened around the cadaver’s neck, when it is drawn out through the hole without disturbing the earth elsewhere. As soon as the cadaver is sacked, the earth replaced, and the grave made to look as near like it was as possible. There are some bunglers however, who have been guilty of leaving the grave open, with fragments of the cadaver’s clothing lying around. They are a disgrace to the profession, and have done much to foster an unfriendly public sentiment in this city.”

is a rope with a hook at one end, a short crowbar, and a spade and a pick. He generally has a “pard,” as it is easier to hunt in couples. He is notified of the “plant” (body), and by personal inspection makes himself familiar with all the surroundings, before the attempt is made. The pick and spade remove the earth from the grave as far as the widest part of the coffin, and with the crowbar, the coffin is shattered, and the rope with the hook end fastened around the cadaver’s neck, when it is drawn out through the hole without disturbing the earth elsewhere. As soon as the cadaver is sacked, the earth replaced, and the grave made to look as near like it was as possible. There are some bunglers however, who have been guilty of leaving the grave open, with fragments of the cadaver’s clothing lying around. They are a disgrace to the profession, and have done much to foster an unfriendly public sentiment in this city.” THE MOST FRUITFUL FIELDS: “The most of the stiffs are raised at Greenlawn cemetery (in Franklin, south of the city), at the Mt. Jackson cemetery (on the grounds of Central State hospital), and at the Poor Farm cemetery (Northwest of the city). So far as I know Crown Hill has never been troubled. Many of the village cemeteries in the neighboring counties are also visited, however, and made to contribute their quota to the cause of science. Some of these village cadavers are those of people who moved in the best society, and besides their value in material for dissection, are rich in jewelry, laces, velvets, etc. The hair of a female subject is alone worth $25. Nothing is wasted, you may be sure. Even the ornaments on the coffin lids are used again..”

THE MOST FRUITFUL FIELDS: “The most of the stiffs are raised at Greenlawn cemetery (in Franklin, south of the city), at the Mt. Jackson cemetery (on the grounds of Central State hospital), and at the Poor Farm cemetery (Northwest of the city). So far as I know Crown Hill has never been troubled. Many of the village cemeteries in the neighboring counties are also visited, however, and made to contribute their quota to the cause of science. Some of these village cadavers are those of people who moved in the best society, and besides their value in material for dissection, are rich in jewelry, laces, velvets, etc. The hair of a female subject is alone worth $25. Nothing is wasted, you may be sure. Even the ornaments on the coffin lids are used again..” The night was a graverobber’s best friend. He lived in it, worked in it, played in it and hid in it. Late at night, these ghouls would steal into cemeteries where a burial had just taken place. In general, fresh graves were best, since the earth had not yet settled and digging was easy work. Laying a sheet or tarp beside the grave, the dirt was shoveled on top of it so the nearby grounds were undisturbed. Most body snatchers could remove the body in less time than it took most people to saddle a horse. They would carefully cover the telltale hole with dirt again, making sure the grave looked the same as it had before they came. Then hurriedly take the body away via the alleyways and sewers of the city, finally delivering the anonymous dearly departed to the back door of a medical school. In time, several of these ghouls began to furnish fresh corpses for sale by murdering the poor, homeless citizens of the city who once stood silent vigil in the alleys as the graverobbers crept past with their macabre cargo in tow.

The night was a graverobber’s best friend. He lived in it, worked in it, played in it and hid in it. Late at night, these ghouls would steal into cemeteries where a burial had just taken place. In general, fresh graves were best, since the earth had not yet settled and digging was easy work. Laying a sheet or tarp beside the grave, the dirt was shoveled on top of it so the nearby grounds were undisturbed. Most body snatchers could remove the body in less time than it took most people to saddle a horse. They would carefully cover the telltale hole with dirt again, making sure the grave looked the same as it had before they came. Then hurriedly take the body away via the alleyways and sewers of the city, finally delivering the anonymous dearly departed to the back door of a medical school. In time, several of these ghouls began to furnish fresh corpses for sale by murdering the poor, homeless citizens of the city who once stood silent vigil in the alleys as the graverobbers crept past with their macabre cargo in tow. In the late 1800s in Indiana, it has been estimated that between 80 to 120 bodies each year were purchased from grave robbers to be used for medical instruction at medical schools and teaching facilities in Indianapolis. An end to the “big business” of grave robbing came as a result of twentieth-century legislation in Indiana which allowed individuals to donate their bodies for this purpose. In 1903, the Indiana General Assembly enacted legislation that created the state anatomical board that was empowered to receive unclaimed bodies from throughout the state and distribute them to medical schools. The act was “for the promotion of anatomical science and to prevent grave desecration.”

In the late 1800s in Indiana, it has been estimated that between 80 to 120 bodies each year were purchased from grave robbers to be used for medical instruction at medical schools and teaching facilities in Indianapolis. An end to the “big business” of grave robbing came as a result of twentieth-century legislation in Indiana which allowed individuals to donate their bodies for this purpose. In 1903, the Indiana General Assembly enacted legislation that created the state anatomical board that was empowered to receive unclaimed bodies from throughout the state and distribute them to medical schools. The act was “for the promotion of anatomical science and to prevent grave desecration.”

Original publish date: January 17, 2011

Original publish date: January 17, 2011 Under close examination the paregoric account in the newspaper clipping begins to unravel. It smacks of a garbled interview by a careless reporter using a badly informed source. Contrary to the clipping, there was no Hoy & James drugstore in Springfield when Lincoln resided there. Lincoln left Springfield, never to return alive, for Washington on February 11, 1861; the Hoy & James drugstore did not begin operations until 1902.

Under close examination the paregoric account in the newspaper clipping begins to unravel. It smacks of a garbled interview by a careless reporter using a badly informed source. Contrary to the clipping, there was no Hoy & James drugstore in Springfield when Lincoln resided there. Lincoln left Springfield, never to return alive, for Washington on February 11, 1861; the Hoy & James drugstore did not begin operations until 1902. Another Lincoln scholar, Walter Oleksy made things worse when he claimed Mary Lincoln was a heavy user of paregoric and had become addicted. Oleksy wrote, “Mary Lincoln was troubled most of her adult life with emotional and psychological problems. In Springfield, to calm her nerves…Mary took paregoric, a popular drug sold in pharmacies in the nineteenth century… Little was then known about the drug’s side effects. For Mary Lincoln the side effects were depression, mood swings, and hallucinations and believed she could communicate with her dead sons.”

Another Lincoln scholar, Walter Oleksy made things worse when he claimed Mary Lincoln was a heavy user of paregoric and had become addicted. Oleksy wrote, “Mary Lincoln was troubled most of her adult life with emotional and psychological problems. In Springfield, to calm her nerves…Mary took paregoric, a popular drug sold in pharmacies in the nineteenth century… Little was then known about the drug’s side effects. For Mary Lincoln the side effects were depression, mood swings, and hallucinations and believed she could communicate with her dead sons.”