Original publish date October 16, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/10/16/the-ghosts-of-playground-productions-in-irvington/

One of the enjoyable aspects of leading ghost tours in Irvington every October is hearing the new ghost stories and spooky tales associated with the buildings we pass along the route. For the past few years, Adam Long and his wife, Andrea, have allowed the tours access to their building, Playground Productions Studio at 5529 N. Bonna Ave., as a jumping-off point to rest and recover after tours. Some of you may know Adam by his stage name, Adam Riviere, a homage to his mother’s whose maiden name. Most importantly, the studio hosts the crew from the Magick Candle every Friday and Saturday night during October for psychic readings for our tour guests and visitors, with the proceeds going to fund the food bank at Gaia Works (6125 E. Washington St.).

Adam graduated from Martinsville High School, studied at Butler University, and attended IUPUI for his graduate work. Adam is an accomplished musician and an artist in his own right. Andrea, originally from London, Kentucky, graduated from North Laurel High School there and from IUPUI in Indianapolis. Andrea is quiet, but when she talks, she speaks with an easy southern drawl that somehow soothes the listener’s ears. As I write this, the couple is celebrating their eleventh wedding anniversary. Adam and Andrea were married in 2014, but have been together since 2008. I first met Adam over a decade ago, when he was a guest on one of my ghost tours. After hearing the Abraham Lincoln ghost train story, which concludes each tour, Adam was sprung. He later informed me that the story resonated with him so deeply that he commissioned an artist friend to create a painting of the ethereal visage for display in his studio office. It comes as no surprise that Adam’s studio is located along the historic corridor of the railroad tracks upon which Lincoln’s funeral train traveled back on April 30, 1865.

Adam’s studio has an interesting history. Adam stated, “It was originally the Coal & Lime Company in Irvington. That was why they wanted to call this area the Coal Yard district, because this is the spot where the trucks would come and pick up the coal to deliver to the areas close by.” The name is a bit of a misnomer, however. While it is true that the company sold “Hoosier Red Pepper Coal” harvested “clean” and “hand picked” from “Indiana’s Richest Coal Mines,” contrary to it’s strict definition, the company specialized in providing hydrated mason’s lime used in the manufacture of common bedrock building materials like glazed tile, fire brick, cement blocks, and common bricks.

On August 3rd, 1922, an ad on page 10 of the Indianapolis Star boasted that the Irvington Coal & Lime Company supplied the “Western Brick as well as other builder’s supplies used in the construction of the new Masonic Temple,” a.k.a. Irvington Masonic Lodge 666, whose cornerstone was laid the year before. Adam was quick to point out to visitors to the property that a portion of the foundation for the old brick factory remains in place several yards away from his studio entrance. Adam informed, “In the early 1950s, a company called Foamcraft bought the building.”

Foamcraft still exists. According to their website, “In 1952, Robert T. Elliott, the founder of our company, started the Foamcraft Rubber Company. As a District Sales Manager for the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, he was responsible for helping to start several foam rubber distributors. Foamcraft was his special passion, though, and in founding our company, he set a foundation for business integrity and dedication to service, as well as a vision to develop long-term relationships with our customers.” Foamcraft makes specialized cushioning used in furniture, beds, minivans, boats, and other products. The company buys large blocks of foam rubber called “Buns” or “Blocks” and cuts them to smaller sizes and shapes as needed by their customers. It was, and remains, a family-run operation with a very high-tenured workforce staffed by generations of families working “cutting foam” for a variety of customer products. The company boasts a 99.9% on-time production and delivery reputation.

Elliott opened his Irvington foam factory on Bonna Avenue in 1957, and it remained there for the next 44 years. Foamcraft briefly relocated in 2001 to a leased building on Post Road before moving to a much larger facility in Greenfield in 2016, where it remains today. Company headquarters are located at 9230 Harrison Park Ct. in between the Fort Benjamin branch library and Peyton Manning Children’s Hospital in Lawrence. Foamcraft also has a manufacturing facility in Elkhart. They never forgot their ties to Irvington, though. Employees referred to the old 20,000 square foot factory, made up of several buildings, simply as the “Bonna.” According to their Web site, employees remember the Bonna facility as “dark and spread out with rooms everywhere. It was sort of claustrophobic with low ceilings, and we worked elbow-to-elbow. It had slippery floors throughout the facility, which sometimes required us to spread sand or sawdust in certain areas.” Despite the distinctly ominous Irvington location’s appearance, inside and out, Foamcraft’s employees described the working atmosphere as “Valhalla.”

One former employee, Jim Quakenbush, recalls that Foamcraft Inc. “ was located on Bonna Ave. just east of Ritter Ave. I worked there for two summers, unloading railroad cars in 1970 & 1971. I have fond memories of working there. Rob Elliott, whose father owned the company, worked with me unloading train cars full of large refrigerator-sized foam rubber “buns”. I think Rob became the CEO and may still be. The warehouse building still stands, but the office building is gone. The railroad track is gone. I really enjoyed the people. My supervisor was Dave Fisher. Great guy. Don Scruggs was a truck driver, funny as hell. Larry Harding worked with me. [The] Sewing department had Ursie Hert, Ralph Wainwright, from Jamaica. Clayton Sneed was a saw operator. Paul was an autistic laborer who used to irritate Ralph. I laughed so hard listening to them argue back and forth. All in good fun. Good memories.”

The old Foamcraft building has quite a history to it, and apparently, a few ghosts as well. Adam recalled, “When I first moved in here, while I locked up at night, stepping out the door, there was a feeling. It wasn’t really ominous, but it definitely gave you a creepy feeling. “ When asked if he feels a presence in the building, Adam stated, “Yes, sometimes when I’m alone in the building, I can hear sharp knocks on the wood in the studio. When I check, nothing is there to explain it.” Adam and Andrea say they don’t ever feel uncomfortable in their building, and they don’t think there is any dark energy connected to their workspace. “We just take it as it comes, we’re used to it now.”

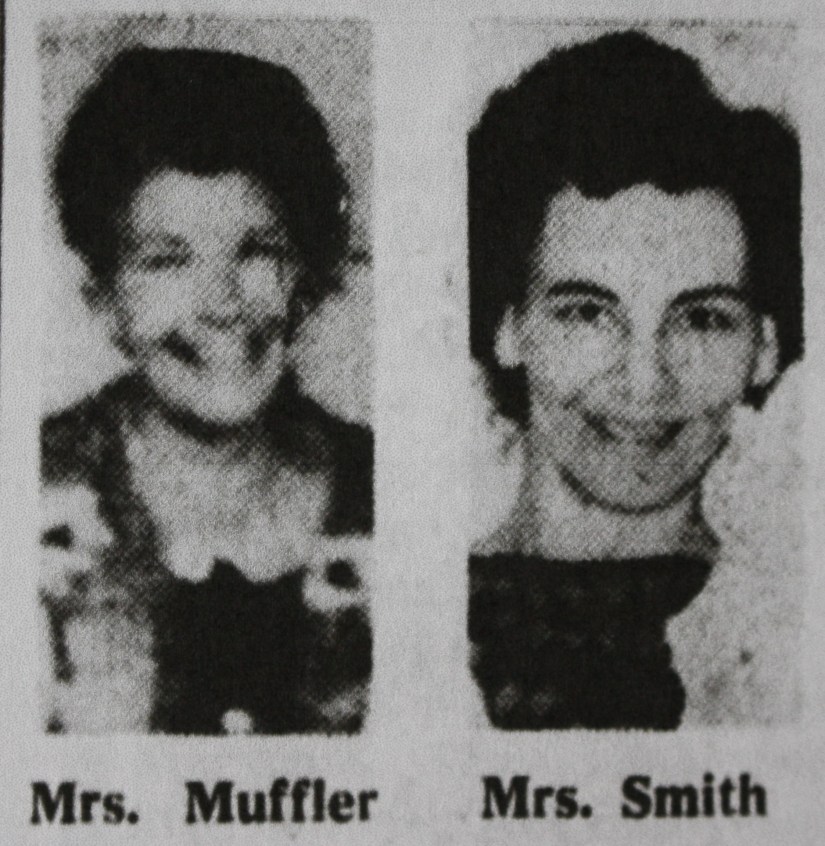

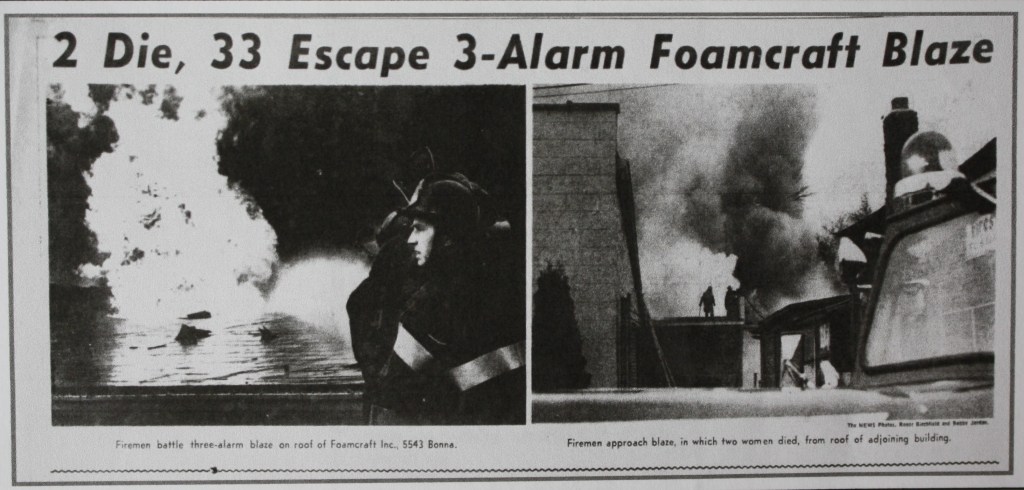

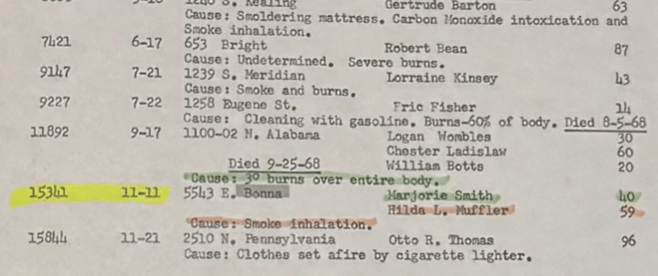

The factory site was visited by tragedy in the autumn of 1968. The front page of the November 12, 1968, Indy News announced “Plant Fire Kills Two Women. 33 Escape Blaze on Eastside.” At 3:34 in the afternoon, firefighters responded to a three-alarm fire at the Foamcraft factory plant. Mrs. Hilda F. Muffler, 59, of 6550 East Troy Avenue, and Mrs. Marjorie J. Smith, 40, of 152 South Summit Street, were killed in the blaze. Mrs. Muffler was employed as a seamstress, and Mrs. Smith as a cutter. Authorities theorized that the two women may have collided and been knocked unconscious during the frenzy to escape the fire. The women died of smoke inhalation and heat. According to the article, Fire Department investigators said the fire was caused by ‘misuse of electricity,’ but did not elaborate.

The article further reports, “An employee, Jack Miller, 56, 250 Audubon Circle, said he was seated at his desk and heard a crackling sound. He looked at a nearby thermostat and said he saw sparks flying from the mechanism. Miller said he ran into another room to get a fire extinguisher, but when he returned, the sparks had ignited stacks of latex foam rubber nearby. There was nothing I could do with the fire extinguisher by the time I got back. It was out of control.” Another Star article quotes Miller as saying he saw a “flash of lightning” come from the wall thermostat and strike a pile of foam. Deputy Marion County Coroner and chief of the fire prevention bureau, Donald E. Bollinger, said the victim’s bodies suffered no burns and were found lying face down perpendicular, one atop the other, in the one-story concrete block plant. The women were found within 4 feet of an office door and only 8 feet from the nearest exit door.

They were discovered to be some 70 feet from the nearest fire damage about 25 minutes after the first alarm had sounded. Other employees challenged the notion that the women panicked trying to escape. Bollinger later theorized that since Mrs. Smith’s coat was found lying next to her body, the women may have attempted to reach a restroom to retrieve their coats and purses before being overcome by smoke.

The fire was spectacular, with flames shooting over 100 feet high in the sky, and the massive plumes of heavy black smoke could be seen from all over the city of Indianapolis. The high-intensity heat hampered firefighters’ efforts to extinguish it quickly. The first alarm came at 3:34, the second at 3:44, and the third at 4:42 pm. Emergency first responders arrived quickly with over 20 pieces of firefighting equipment and 65 firefighters. John T. O’Brien, owner of the Bonna Printing Company at 5543 Bonna Avenue, reported that his adjacent building suffered only minor smoke and water damage during the conflagration. Other adjacent businesses, Krauter Equipment Company & the Firestone Tire & Rubber Company, also reported minor damage. At 12:17 am, the blaze briefly reignited, and firemen were again called to extinguish the flames. That second fire had ignited beneath the collapsed roof of the factory and was brought under control at 1:17 am.

The Foamcraft building was destroyed in the inferno. Investigators determined the fire started along the north wall of the “blackened pillow room” on the northeast corner of the building. Deputy Chief Bollinger later speculated that the fire could have been prevented if the wall receptacle box, which contained the mechanism controlling the heating blowers, had been properly covered. One unnamed employee told Bollinger that he tried to make a metal cover for the box the week before the blaze, but was shocked during the attempted installation and was unable to do so. That same employee said that he had informed company officials of the problem, but it had not been fixed yet.

Learning that Adam and Andrea’s building may have a resident ghost, one could believe that the spirits of Playgorund Productions Studio are those of the tragic victims of the Foamcraft factory fire from 1968, but that does not appear to be the case. Tim Poynter, intuitive psychic empath who has worked with me on the tours for decades and now spends every October Friday and Saturday night in the building, admits that he encounters those spirits regularly, “But they aren’t necessarily attached to the building. They seem to be just passing through. Sometimes the tour guests bring them, and at other times, they are brought in by the readers.” Likewise, longtime tour volunteer Cindy Adkins, who was featured as a psychic intuitive in an episode of Zak Bagans’ Ghost Adventures in 2019, does not feel a resident ghost in the building. “They’re not in here permanently. I don’t feel them inside, but I do think some spirits are roaming around outside the building.” said Cindy. Indeed, it should be noted that the spot where the two employees died is located outside the studio, about 20-30 yards northwest of the door.

Today, Playground Productions Studio is a far cry from the old, dark, and spooky, chopped-up Foamcraft factory. The working studio is now full of light and texture. Walls are constructed of a naturally grounded hardwood facia and are peppered by soft blankets buffering any echoes and sounds that might affect the recording work. The artists, bands, and performers who regularly work or visit the Playground are joyful and carefree whenever there is an event or party going on. Knowing the depth of feeling that former Foamcraft employees have for the old “Bonna” location, it is easy to imagine that if there are spirits hovering around the property, inside or out, they do so with mirth and glee.

Foamcraft has created a fantastic, informative, and historical video with scenes shot at the old factory on Bonna. It can be found on the Web at: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/foamcraft-inc-_the-story-of-foamcraft-inc-activity-7089985534889975808-y92J/

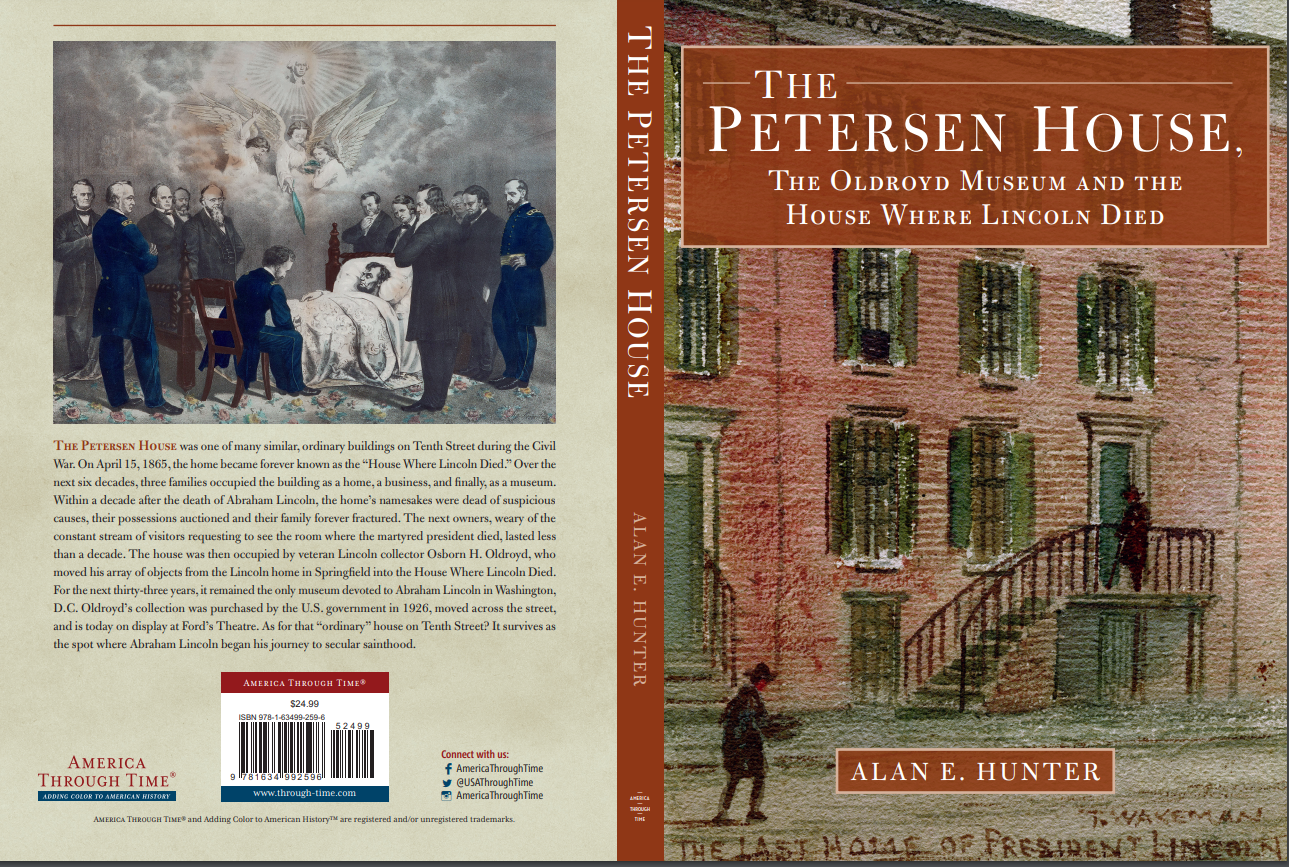

Although Lincoln and Riley died a half-century apart, the men had much in common. The two were considered the state’s most famous Hoosiers (that is until John Dillinger died in 1934) and their names were often linked in speeches, newspaper articles, books and periodicals in the first fifty years of the 20th century. One of my favorite quotes found while searching the virtual stacks of old newspapers comes from the July 20, 1941 Manhattan Kansas Morning Chronicle: “If you want to succeed in life, you might run a better chance if you live in a house with green shutters. Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain and James Whitcomb Riley all lived in such houses.” Lincoln and Riley epitomized everything that was good about being a Hoosier, right down to the color of their green window shutters.

Although Lincoln and Riley died a half-century apart, the men had much in common. The two were considered the state’s most famous Hoosiers (that is until John Dillinger died in 1934) and their names were often linked in speeches, newspaper articles, books and periodicals in the first fifty years of the 20th century. One of my favorite quotes found while searching the virtual stacks of old newspapers comes from the July 20, 1941 Manhattan Kansas Morning Chronicle: “If you want to succeed in life, you might run a better chance if you live in a house with green shutters. Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain and James Whitcomb Riley all lived in such houses.” Lincoln and Riley epitomized everything that was good about being a Hoosier, right down to the color of their green window shutters.

Oldroyd, a thrice-wounded Civil War veteran, collector, curator and author, is perhaps the father of the house museum in America. One of Oldroyd’s books, a compilation of poems entitled, “The Poets’ Lincoln— Tributes In Verse To The Martyred President”, was published in 1915. James Whitcomb Riley’s poem, A Peaceful Life with the name “Lincoln” in parenthesis as a sub-title can be found there on page 31. In Oldroyd’s version, the first line differs from Riley’s original version. Riley’s handwritten original (found today in the archives of the Lilly Library on the Bloomington campus of Indiana University) begins: “Peaceful Life:-toil, duty, rest-“. Oldroyd’s book version begins; “A peaceful life —just toil and rest—.” Interestingly, the Oldroyd version has become the standard. And there you have it. Oldroyd’s influence is subtle, his name largely unknown, yet he stays with us to this day.

Oldroyd, a thrice-wounded Civil War veteran, collector, curator and author, is perhaps the father of the house museum in America. One of Oldroyd’s books, a compilation of poems entitled, “The Poets’ Lincoln— Tributes In Verse To The Martyred President”, was published in 1915. James Whitcomb Riley’s poem, A Peaceful Life with the name “Lincoln” in parenthesis as a sub-title can be found there on page 31. In Oldroyd’s version, the first line differs from Riley’s original version. Riley’s handwritten original (found today in the archives of the Lilly Library on the Bloomington campus of Indiana University) begins: “Peaceful Life:-toil, duty, rest-“. Oldroyd’s book version begins; “A peaceful life —just toil and rest—.” Interestingly, the Oldroyd version has become the standard. And there you have it. Oldroyd’s influence is subtle, his name largely unknown, yet he stays with us to this day.

The Opera House hosted the first performance of the inflammatory anti-slavery play “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and its location straddling the North-South boundary caused quite a stir in the days leading up to the Civil War. During the “War of the Rebellion”, the building was used as “Hospital No. 9” and soldiers from both sides of the conflict could often be found lying side-by-side within its walls. In April of 1862, the steamer “H.J. Adams” delivered 200 wounded soldiers to the converted Opera House fresh from the killing fields of Shiloh. In these years before sterilization set the standard of hospital care, a wounded soldier sent to Hospital No. 9, as with any hospital North or South of the Mason-Dixon line, might as well have been handed a death sentence. Many a soldier in Hospital No. 9 would write letters telling friends and family that he was on the mend from a minor battle wound one day, only to die unexpectedly the next day from disease.

The Opera House hosted the first performance of the inflammatory anti-slavery play “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and its location straddling the North-South boundary caused quite a stir in the days leading up to the Civil War. During the “War of the Rebellion”, the building was used as “Hospital No. 9” and soldiers from both sides of the conflict could often be found lying side-by-side within its walls. In April of 1862, the steamer “H.J. Adams” delivered 200 wounded soldiers to the converted Opera House fresh from the killing fields of Shiloh. In these years before sterilization set the standard of hospital care, a wounded soldier sent to Hospital No. 9, as with any hospital North or South of the Mason-Dixon line, might as well have been handed a death sentence. Many a soldier in Hospital No. 9 would write letters telling friends and family that he was on the mend from a minor battle wound one day, only to die unexpectedly the next day from disease. Judy recalls how in 2001, her youngest son David was down in the building’s cellar “fishing” for old bottles in a cistern that he had removed the concrete covering from. “He was laying on his stomach down there alone when he suddenly felt someone tap him on the shoulder” she says, “he looked around expecting to see the source of the poking, but saw that he was still down there alone. Since that time, David does not like to be in the basement by himself.”

Judy recalls how in 2001, her youngest son David was down in the building’s cellar “fishing” for old bottles in a cistern that he had removed the concrete covering from. “He was laying on his stomach down there alone when he suddenly felt someone tap him on the shoulder” she says, “he looked around expecting to see the source of the poking, but saw that he was still down there alone. Since that time, David does not like to be in the basement by himself.” Spirits of a Civil War soldier and a woman in an old fashioned Antebellum Era dress have been seen lounging around the cafe area by a few folks. “Every once in awhile, we’ll get a psychic coming through here telling us that they see the spirits of several Civil War soldiers around the entire building and sense sadness in the basement area.” says Gwinn.

Spirits of a Civil War soldier and a woman in an old fashioned Antebellum Era dress have been seen lounging around the cafe area by a few folks. “Every once in awhile, we’ll get a psychic coming through here telling us that they see the spirits of several Civil War soldiers around the entire building and sense sadness in the basement area.” says Gwinn.

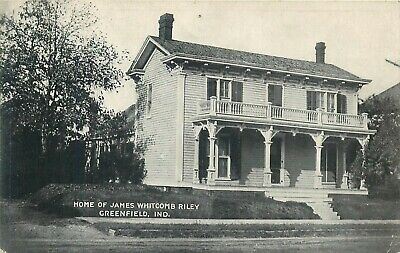

What we don’t know is how Allie came to the Riley home. Depending on who you talk to, Allie was; a friend of the family, a castoff of the Orphan Train movement (1854-1929), or she was brought to the home by her uncle, John Rittenhouse, who brought the young girl to Greenfield where he “dressed her in black” and “bound her out to earn her board and keep”. Ultimately, Mary Alice was taken in by Captain Reuben Riley as a servant to help his wife Elizabeth with the housework and her four children; John, James, Elva May and Alex.

What we don’t know is how Allie came to the Riley home. Depending on who you talk to, Allie was; a friend of the family, a castoff of the Orphan Train movement (1854-1929), or she was brought to the home by her uncle, John Rittenhouse, who brought the young girl to Greenfield where he “dressed her in black” and “bound her out to earn her board and keep”. Ultimately, Mary Alice was taken in by Captain Reuben Riley as a servant to help his wife Elizabeth with the housework and her four children; John, James, Elva May and Alex. When James was eleven, he asked Allie what he would be when he grew up. “Perhaps you’ll be a lawyer, like your father,” she suggested. “Or maybe someday, you’ll be a great poet.” Allie may have been the first to put this idea in James’ mind, but it is known that his mother and father were both gifted storytellers. Riley often shared his vivid childhood recollection of Allie climbing the stairs every night to her lonesome “rafter room” in the attic. And with every careful step leaning down and patting each stair affectionately as she called them by name.

When James was eleven, he asked Allie what he would be when he grew up. “Perhaps you’ll be a lawyer, like your father,” she suggested. “Or maybe someday, you’ll be a great poet.” Allie may have been the first to put this idea in James’ mind, but it is known that his mother and father were both gifted storytellers. Riley often shared his vivid childhood recollection of Allie climbing the stairs every night to her lonesome “rafter room” in the attic. And with every careful step leaning down and patting each stair affectionately as she called them by name.

I, like many fellow Hoosiers, am drawn to this particular poem because it was written to be recited aloud and not necessarily to be read from a page. Written in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect, the words can be difficult to read in modern times. Riley dedicates his poem “to all the little ones,” which immediately gets the attention of his intended audience; children. The alliteration, phonetic intensifiers and onomatopoeia add sing-song effects to the rhymes that become clearer when read aloud. The exclamatory refrain ending each stanza is urgently spoken adding more emphasis as the poem goes on. It is written in first person which makes the poem much more personal. Simply stated, the poem is read exactly as young “Bud” Riley recalled Allie telling it to him when he was a wide-eyed little boy.

I, like many fellow Hoosiers, am drawn to this particular poem because it was written to be recited aloud and not necessarily to be read from a page. Written in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect, the words can be difficult to read in modern times. Riley dedicates his poem “to all the little ones,” which immediately gets the attention of his intended audience; children. The alliteration, phonetic intensifiers and onomatopoeia add sing-song effects to the rhymes that become clearer when read aloud. The exclamatory refrain ending each stanza is urgently spoken adding more emphasis as the poem goes on. It is written in first person which makes the poem much more personal. Simply stated, the poem is read exactly as young “Bud” Riley recalled Allie telling it to him when he was a wide-eyed little boy. Riley wrote another poem about her titled, “Where Is Mary Alice Smith?” In this poem he depicts the little orphan girl falling in love with a soldier boy who was killed during the war which caused her to die of grief. In truth, after leaving the Riley’s employ, Mary Alice went to work in a Tavern on the National Road in the town of Philadelphia where she met her husband John Gray and their marriage produced seven children.

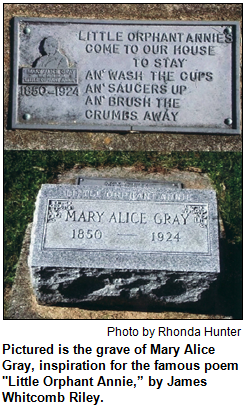

Riley wrote another poem about her titled, “Where Is Mary Alice Smith?” In this poem he depicts the little orphan girl falling in love with a soldier boy who was killed during the war which caused her to die of grief. In truth, after leaving the Riley’s employ, Mary Alice went to work in a Tavern on the National Road in the town of Philadelphia where she met her husband John Gray and their marriage produced seven children. Jut remember, as you travel out to the old Riley home on U.S. Highway 40 (the old National Road) you’re bound to pass through the remains of a little pike town called Philadelphia. The road starts to rise just past the Philadelphia signpost and there on the right is a small cemetery. Stop your car and walk towards the oldest headstones under the tall trees in back of the old burial ground. It is there that you will find the final resting place of Mary Alice Smith Gray, Riley’s beloved “Little Orphant Annie.” Its best you go before twilight though because should you delay past nightfall, “the Gobble-uns ‘at gits you ef you don’t watch out!”

Jut remember, as you travel out to the old Riley home on U.S. Highway 40 (the old National Road) you’re bound to pass through the remains of a little pike town called Philadelphia. The road starts to rise just past the Philadelphia signpost and there on the right is a small cemetery. Stop your car and walk towards the oldest headstones under the tall trees in back of the old burial ground. It is there that you will find the final resting place of Mary Alice Smith Gray, Riley’s beloved “Little Orphant Annie.” Its best you go before twilight though because should you delay past nightfall, “the Gobble-uns ‘at gits you ef you don’t watch out!”

If he was fearful, Joseph Brown did not show it as he sat down for what would be his last meal. At 5:30 PM, Mary Brown sent her two older children to the Smith’s, neighbors whose home was frequently visited by Wade, the children and Mary Brown. Mary instructed the children that she would come to get them after dinner and that Wade would play fiddle that evening to entertain at the Smith home. During the course of the evening, Wade asked Brown to borrow his buggy. He stated that he wanted to sell a horse to Irvington’s Dr. long. Brown agreed. As dinner ended, Brown went into the front yard to work on an ax handle. Wade was hitching the horse to the buggy.

If he was fearful, Joseph Brown did not show it as he sat down for what would be his last meal. At 5:30 PM, Mary Brown sent her two older children to the Smith’s, neighbors whose home was frequently visited by Wade, the children and Mary Brown. Mary instructed the children that she would come to get them after dinner and that Wade would play fiddle that evening to entertain at the Smith home. During the course of the evening, Wade asked Brown to borrow his buggy. He stated that he wanted to sell a horse to Irvington’s Dr. long. Brown agreed. As dinner ended, Brown went into the front yard to work on an ax handle. Wade was hitching the horse to the buggy. The investigation by Coroner George Wishard, namesake of today’s Wishard Hospital, was thorough and damning to Wade. During his investigation at the Brown farm, Wishard “found a board, probably a small kneading tray, hidden away under the shed… Which is bespattered with blood.” Signs of a violent struggle and blood were found in the yard. The mountain of evidence was building against Wade. But did he act alone? Or was “Bloody Mary” Brown, as one of the contemporary newspapers dubbed her, more involved than she claimed?

The investigation by Coroner George Wishard, namesake of today’s Wishard Hospital, was thorough and damning to Wade. During his investigation at the Brown farm, Wishard “found a board, probably a small kneading tray, hidden away under the shed… Which is bespattered with blood.” Signs of a violent struggle and blood were found in the yard. The mountain of evidence was building against Wade. But did he act alone? Or was “Bloody Mary” Brown, as one of the contemporary newspapers dubbed her, more involved than she claimed?