Original publish date: July 30, 2020

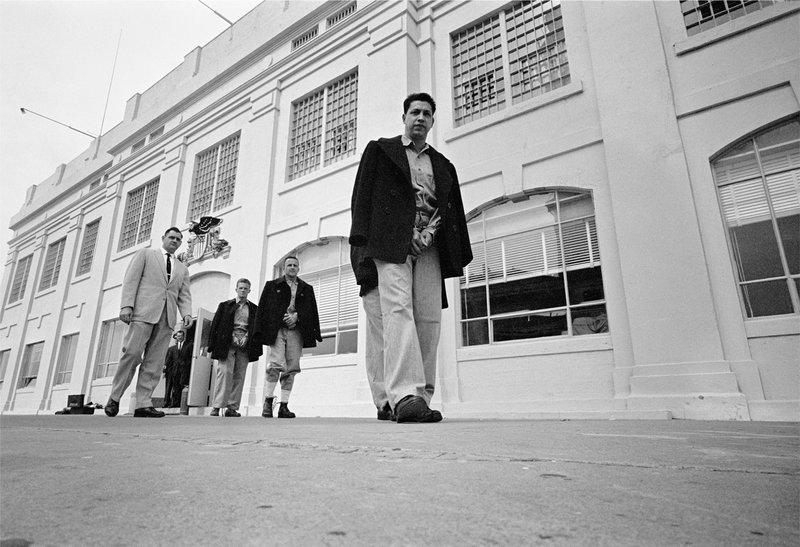

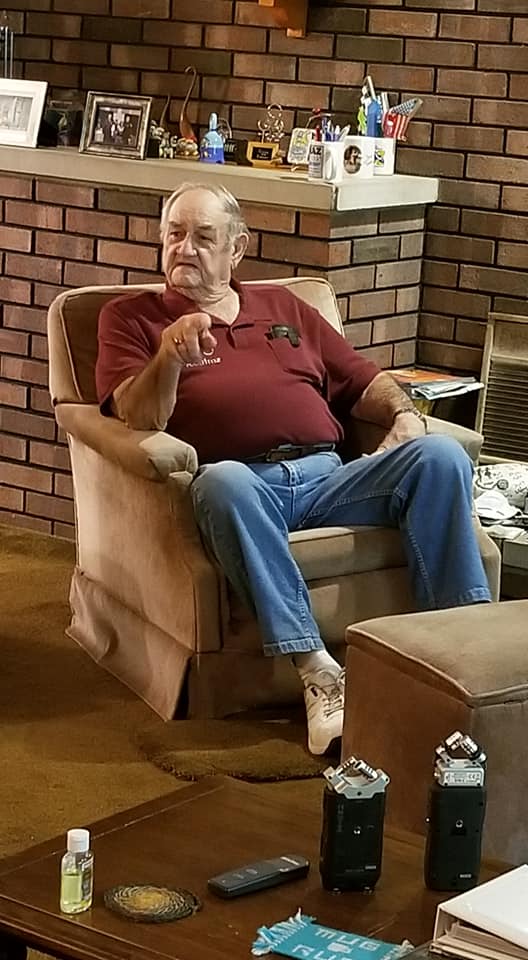

I asked guard Jim Albright what he remembers about the closing of Alcatraz prison in March of 1963, in particular the visit by Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. “Oh yeah. I remember. He toured the island and had about 50 bodyguards all around him. He didn’t want any of those bad guys to get near him.” Jim can still recall the names and numbers of the infamous inmates on the island when he was there. “Whitey Bulger # 1428, Alvin Creepy Karpis # 325. Alvin was the lowest number left when I was there. Alvin did more time on the island than any other convict. He did just straight at 26 years.” Jim recalls both Bulger and Karpis as “good cons”, both were “quiet and respectful when they spoke to you.” However Jim does say this about Karpis, a notorious kidnapper with the Ma Barker gang, “He was creepy, oh yeah, he was creepy.” Jim states, “I always treated them like I would have wanted to be treated had I been the convict. My job was not to punish them, my job was security.”

Jim recalls, “Everybody talks about that escape in the Clint Eastwood movie, but I was on duty for the last escape from Alcatraz. John Paul Scott # 1503. December 16, 1962. That was 25 years, almost to the day from the first escape. I was in the control center. I got the call on the red phone, that’s the emergency phone, and you ‘dial the deuces’ as they call it, 222. ‘Jim get me some help, I got a couple missing from the kitchen basement’ was all I heard.” It was Jim Albright’s responsibility to call out the news, order the boat and man the towers for that final escape. Once again displaying his amazing recall after nearly 60 years, Jim says, “Darrel and Don Pickens, they were from Arizona, and they were both red haired and red freckles, red faced…I put them out in # 2 and # 3 towers and every thing’s going along and pretty soon they’re yelling.” They had found Scott’s fellow escapee Daryl D. Parker clinging for life on “Little Alcatraz” (a small rock in San Francisco Bay roughly 80 yards off the northwest side of the Island). Scott, by now naked and battered senseless, came to rest on a rocky outcropping in the bay near Fort Point. He was brought back to the Rock.

“I escorted the last inmate off the island, Frank Weatherman # 1576. We never had reporters, they were never allowed on the island but that day (of the closing) we probably had 250 of ’em, from all walks of news. One of ’em almost got in line as we’re heading out and asked me ‘what do you think about this?’ as we’re walking and I said, ‘Hey! I’m still working. My job is going on right now. The biggest thing I gotta watch right now is that one of you damned idiots don’t give ’em something they can escape with. Afterwards, I thought, Jim, keep your big mouth shut.” I asked Cathy where she was during that final prisoner walk down to the dock and she answered, “I was on the balcony watching. I was filming it.” Jim says, “We took the film to get it developed, but never got it back.” Cathy answers, “Somebody’s got it but we don’t.” Cathy also notes, “Well the inmates did not want Alcatraz to close. Some of them cried when they left because where they were going they might have to go to a 4-or-5-man cell, Alcatraz was single cells and they liked that.” Jim adds, “Some of them went, and Creepy Karpis was one of em, to McNeil Island in Washington and they had 10-man cells up there. Creepy, for 25, 26 years almost was used to a one man cell. They finally paroled him and deported him to Canada…from there he went to Spain. I guess he couldn’t take being free, cause he hung himself.”

Jim missed Robert Stroud, the infamous “Birdman of Alcatraz”, by just a few days. “I went there in August and he left in July. But I heard all the stories about him,” Jim recalls. “He was not liked by inmates or staff, either one. You talk about somebody no good, that was him…He was a weird old, nasty guy.” Jim and Cathy remained on the island for three months after that last inmate was escorted onto the boat by Officer Albright himself. It was only afterwards that the couple allowed themselves a little luxury, “We were there March to June. We moved from 64 building over across the parade ground to the city side…They had what they called B & C apartments, these were nicer apartments, they had fireplaces in them.” Jim smiles as he recalls Alcatraz historian and author Jerry Champion jokingly asking, “You had a fireplace did ya? Where’d you get your firewood?” (There are no trees on Alcatraz island).

Jim guesses that there may be a “half a dozen or less” Alcatraz guards still living, and “two of them are in wheelchairs” and the former guard estimates the same for the former convicts. Cathy notes that the inmates used to come to the reunions too and Jim recalls that it took awhile for the inmates to show up because “they were ashamed of what the guards would think, ya know.” But spend five minutes with Jim Albright and you quickly realize that he was never one to hold a grudge. Officer Albright is simply not the judging kind. Jim Albright is a people person. He enjoys meeting people and loves to see their reactions when he shares his story, especially when he reveals that they lived on the island. “As soon as I tell them that and point to my wife, it’s “FWEET!” (he says with a whistle and grin), they go right over to her and I’ve lost ’em.”

For many years, Jim and Cathy traveled by train from Terre Haute to San Francisco, a 2 1/4 day’s travel from nearby Galesburg, Illinois. “There used to be 150 people come out to those reunions, but then it got down to 30 cause there’s just nobody left.” Because of the current situation with Covid-19, the couple’s trip has been postponed. Cathy admits, “Well, we’re all getting older” and Jim chimes in, “And that’s the thing about not going in August, that means that last August was probably our last time going out there. The odds are against us.” Jim and Cathy fear that the alumni association will soon be no more. “There’s just not enough of ’em left,” Cathy says.

A week after our visit to Jim and Cathy Albright, the United States Supreme Court lifted the ban on executions at the Terre Haute penitentiary located a mere three miles from their front door. At the time of this writing, there had been three executions in four days. While there were never any State sanctioned executions at Alcatraz, there was not much rehabilitation taking place there either. Convicts were different back then, some actually viewed it as a profession. When asked about the convicts of today, Jim simply shakes his head and says, “They were more like professional convicts ya know ‘I did the crime, I’ll do the time’. It’s just not the same. It’s a different world now.”

A week after our visit to Jim and Cathy Albright, the United States Supreme Court lifted the ban on executions at the Terre Haute penitentiary located a mere three miles from their front door. At the time of this writing, there had been three executions in four days. While there were never any State sanctioned executions at Alcatraz, there was not much rehabilitation taking place there either. Convicts were different back then, some actually viewed it as a profession. When asked about the convicts of today, Jim simply shakes his head and says, “They were more like professional convicts ya know ‘I did the crime, I’ll do the time’. It’s just not the same. It’s a different world now.”

In his book, Jim wrote quite eloquently of his feelings on that last day, “Emotions of prison personnel were very strong and it was hard to accept that all the convicts were gone…I boarded the boat for the last time as a guard on Alcatraz. I though to myself, what an experience I had just completed, and how fast the time went by. I felt tears grow in my eyes as the boat went across the water to Fort Mason.” I asked the couple individually, if they could make one statement about the Rock, what would it be? Cathy answered, “Well, I really liked the place. I did not want to leave. It was one big family… It was something special. It was home.” Jim reflected for a few moments, titled his head back as if looking through the mist of time, and replied, “A very enjoyable life living on the island and a very safe place to raise our children.”

Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary has been closed for over 57 years now. During that time it has become more myth than reality. Alcatraz Island encompasses a total of 22 acres in the center of San Francisco Bay. It opened to the public in fall 1973 and since that time has hosted millions of people from every corner of the world. The flood of people who once lived on the island during the time it was the world’s most famous prison has trickled to a slow drip. However, there remains one couple living on the western edge of the Hoosier state who know that sometimes, even if they don’t consider themselves as such, legends are real and history is the foundation of all that is worthy in life.

What we don’t know is how Allie came to the Riley home. Depending on who you talk to, Allie was; a friend of the family, a castoff of the Orphan Train movement (1854-1929), or she was brought to the home by her uncle, John Rittenhouse, who brought the young girl to Greenfield where he “dressed her in black” and “bound her out to earn her board and keep”. Ultimately, Mary Alice was taken in by Captain Reuben Riley as a servant to help his wife Elizabeth with the housework and her four children; John, James, Elva May and Alex.

What we don’t know is how Allie came to the Riley home. Depending on who you talk to, Allie was; a friend of the family, a castoff of the Orphan Train movement (1854-1929), or she was brought to the home by her uncle, John Rittenhouse, who brought the young girl to Greenfield where he “dressed her in black” and “bound her out to earn her board and keep”. Ultimately, Mary Alice was taken in by Captain Reuben Riley as a servant to help his wife Elizabeth with the housework and her four children; John, James, Elva May and Alex. When James was eleven, he asked Allie what he would be when he grew up. “Perhaps you’ll be a lawyer, like your father,” she suggested. “Or maybe someday, you’ll be a great poet.” Allie may have been the first to put this idea in James’ mind, but it is known that his mother and father were both gifted storytellers. Riley often shared his vivid childhood recollection of Allie climbing the stairs every night to her lonesome “rafter room” in the attic. And with every careful step leaning down and patting each stair affectionately as she called them by name.

When James was eleven, he asked Allie what he would be when he grew up. “Perhaps you’ll be a lawyer, like your father,” she suggested. “Or maybe someday, you’ll be a great poet.” Allie may have been the first to put this idea in James’ mind, but it is known that his mother and father were both gifted storytellers. Riley often shared his vivid childhood recollection of Allie climbing the stairs every night to her lonesome “rafter room” in the attic. And with every careful step leaning down and patting each stair affectionately as she called them by name.

I, like many fellow Hoosiers, am drawn to this particular poem because it was written to be recited aloud and not necessarily to be read from a page. Written in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect, the words can be difficult to read in modern times. Riley dedicates his poem “to all the little ones,” which immediately gets the attention of his intended audience; children. The alliteration, phonetic intensifiers and onomatopoeia add sing-song effects to the rhymes that become clearer when read aloud. The exclamatory refrain ending each stanza is urgently spoken adding more emphasis as the poem goes on. It is written in first person which makes the poem much more personal. Simply stated, the poem is read exactly as young “Bud” Riley recalled Allie telling it to him when he was a wide-eyed little boy.

I, like many fellow Hoosiers, am drawn to this particular poem because it was written to be recited aloud and not necessarily to be read from a page. Written in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect, the words can be difficult to read in modern times. Riley dedicates his poem “to all the little ones,” which immediately gets the attention of his intended audience; children. The alliteration, phonetic intensifiers and onomatopoeia add sing-song effects to the rhymes that become clearer when read aloud. The exclamatory refrain ending each stanza is urgently spoken adding more emphasis as the poem goes on. It is written in first person which makes the poem much more personal. Simply stated, the poem is read exactly as young “Bud” Riley recalled Allie telling it to him when he was a wide-eyed little boy. Riley wrote another poem about her titled, “Where Is Mary Alice Smith?” In this poem he depicts the little orphan girl falling in love with a soldier boy who was killed during the war which caused her to die of grief. In truth, after leaving the Riley’s employ, Mary Alice went to work in a Tavern on the National Road in the town of Philadelphia where she met her husband John Gray and their marriage produced seven children.

Riley wrote another poem about her titled, “Where Is Mary Alice Smith?” In this poem he depicts the little orphan girl falling in love with a soldier boy who was killed during the war which caused her to die of grief. In truth, after leaving the Riley’s employ, Mary Alice went to work in a Tavern on the National Road in the town of Philadelphia where she met her husband John Gray and their marriage produced seven children. Jut remember, as you travel out to the old Riley home on U.S. Highway 40 (the old National Road) you’re bound to pass through the remains of a little pike town called Philadelphia. The road starts to rise just past the Philadelphia signpost and there on the right is a small cemetery. Stop your car and walk towards the oldest headstones under the tall trees in back of the old burial ground. It is there that you will find the final resting place of Mary Alice Smith Gray, Riley’s beloved “Little Orphant Annie.” Its best you go before twilight though because should you delay past nightfall, “the Gobble-uns ‘at gits you ef you don’t watch out!”

Jut remember, as you travel out to the old Riley home on U.S. Highway 40 (the old National Road) you’re bound to pass through the remains of a little pike town called Philadelphia. The road starts to rise just past the Philadelphia signpost and there on the right is a small cemetery. Stop your car and walk towards the oldest headstones under the tall trees in back of the old burial ground. It is there that you will find the final resting place of Mary Alice Smith Gray, Riley’s beloved “Little Orphant Annie.” Its best you go before twilight though because should you delay past nightfall, “the Gobble-uns ‘at gits you ef you don’t watch out!”

Grant immediately relieved Rosecrans in Chattanooga and replaced him with Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, soon to be known as “The Rock of Chickamauga”. Devising a plan known as the “Cracker Line”, Thomas’s chief engineer, William F. “Baldy” Smith opened a new supply route to Chattanooga, helping to feed the starving men and animals of the Union army. Upon re-provisioning and reinforcing, the morale of Union troops lifted and in late November, they went on the offensive. The Battles for Chattanooga ended with the capture of Lookout Mountain, opening the way for the Union Army to invade Atlanta, Georgia, and the heart of the Confederacy.

Grant immediately relieved Rosecrans in Chattanooga and replaced him with Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, soon to be known as “The Rock of Chickamauga”. Devising a plan known as the “Cracker Line”, Thomas’s chief engineer, William F. “Baldy” Smith opened a new supply route to Chattanooga, helping to feed the starving men and animals of the Union army. Upon re-provisioning and reinforcing, the morale of Union troops lifted and in late November, they went on the offensive. The Battles for Chattanooga ended with the capture of Lookout Mountain, opening the way for the Union Army to invade Atlanta, Georgia, and the heart of the Confederacy.