Original Publish Date January 6, 2016. Republished January 23, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2016/01/14/the-lyric-theatre-part-1/

This week the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. will open a new exhibit called “Sinatra at 100” honoring Frank Sinatra’s 100th birthday last December 12th. The National Museum of American History will surely put up a classy display, but I seriously doubt that our fair city will be mentioned at all… but we should be.

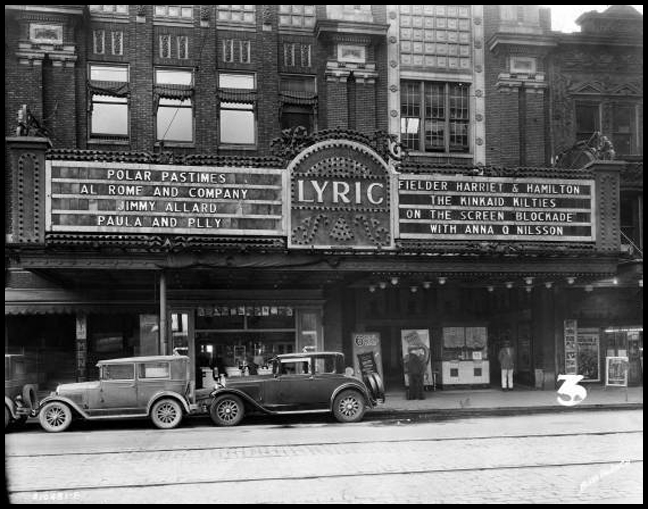

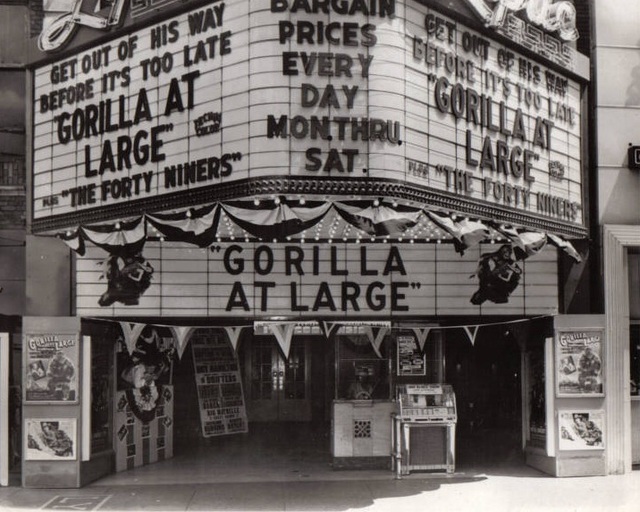

Located at 135 N. Illinois Street there once stood a theatre with as rich a pop-culture history as any in Indianapolis. When the Lyric Theatre opened in February of 1906, it was a room with about 200 folding chairs arranged in rows. A carbon arc light projector rested on a tripod in the rear of the theatre. The film was mounted on a reel and fed at a rate of 16-18 frames per second between the arc light and the projector lens, which magnified the image so that it could be projected onto a screen. Early projectors simply dumped the projected film into a basket on the floor. Projectors were hand-cranked, and the projectionist could speed up or slow down the action on the screen by “over-cranking” or “under-cranking.”

The film stock itself was made from nitrocellulose, a chemical cousin to explosives used by the military in World War I. The highly flammable film and the extremely hot light source meant that fire was a very real threat. In fact, the incidence of projector-related fires over the first ten years of movie houses produced some of the worst tragedies in our country’s history, capable of killing hundreds of people in an instant. For this reason, a larger 1400-seat Lyric theatre was built on the property six years later.

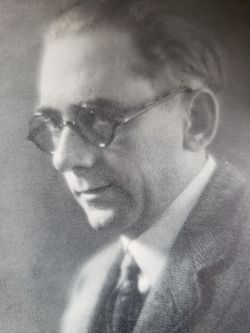

The new Lyric was constructed by the Central Amusement Co. for $75.000, built by the Halstead-Moore Co., and designed by architect Herman L. Bass, who designed Indianapolis Motor Speedway co-founder James A. Allison’s mansion, now on the campus of Marian College. This upgrade included fireproof materials inside and exterior walls of concrete, steel, and artistic brick accented by white terra-cotta trim.

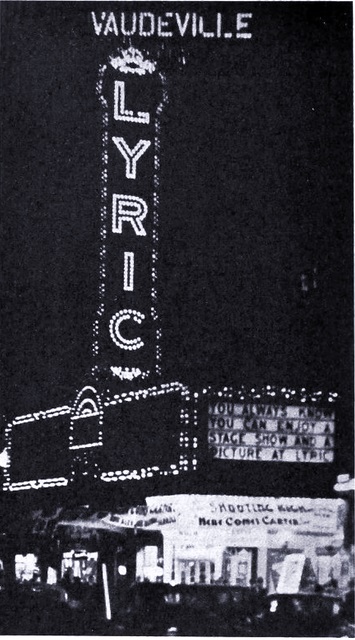

On April 20, 1919, the Lyric was again closed for remodeling, this design courtesy of architect Kurt Vonnegut Sr., a well-known name that still resonates through town to this day. This facelift left only three original walls standing and created a new lobby on the south. The stage that originally faced west now faced south. It had its grand reopening on September 1, 1919. The Lyric underwent its last major remodel in 1926, adding state-of-the-art air conditioning and modern stage lighting systems. This remodel cost $185,000 and included construction of a new four-story building featuring a new main entrance, and lobby with executive offices above.

The new Lyric, with its shiny marble and gold lobby lined with French mirrors and six French crystal chandeliers, was considered to be one of the finest theaters in Indiana. 300 more seats were added as was a new basement that housed rehearsal areas and dressing rooms named for cities on its doors. A new marquee was added above the front door. At 10 feet high, 50 feet long, and 16 feet deep, it held up to 440 letters and was said to be the largest of its kind in the state. The following year a new Marr-Colton pipe organ was added for $30,000.00, which, like the marquee, was the largest in the state.

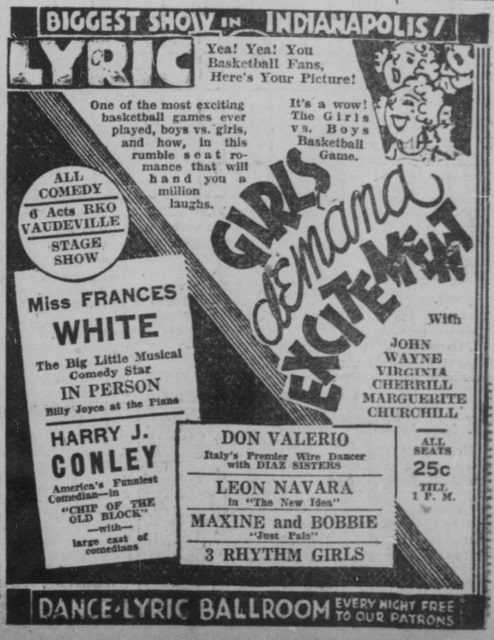

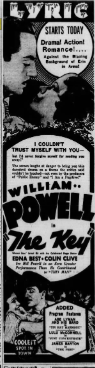

The Lyric began life showing films scored with music provided by live musicians. Then came Vaudeville, talkies, and finally big screen epics similar to today. World War I led to the Roaring Twenties, then to the Great Depression, and into the gangster era whose Hoosier outlaw roots extended to the doorway of the Lyric itself. The Lyric survived the Depression by featuring an eclectic mix of movies, Vaudeville acts, stage shows and live musicals.

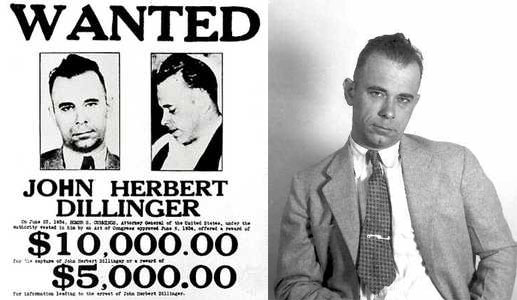

A week after the death of Hoosier Public Enemy # 1 John Dillinger on July 22, 1934, his family signed a 5-month vaudeville contract at the Lyric theatre that expired on New Year’s Eve. Crowds mobbed the theatre to hear stories from and ask questions of, John Dillinger, Sr. about his famous outlaw son. The 15-minute show was billed as “Crime doesn’t pay” even though it cost patrons an extra 15 cents to see it. Here, Dillinger Sr. and his sister Audrey fielded questions from the crowd. The show traveled to the Great Lakes, Texas Centennial and San Diego Expositions, and Chicago World’s Fair, which gangster Dillinger had famously visited while alive. Rumor persists that the Lyric was also a favorite hangout for John Dillinger. After all, everyone knows that Dillinger died outside of a Chicago movie theatre.

Edgar Bergen (only weeks before he introduced his “dummy” Charlie McCarthy) played the Lyric in 1934 in a vaudeville act that included a trio of sisters calling themselves the “Queens of Harmony” who later became known as The Andrews Sisters. Red Skelton was a 1930s performer at the Lyric known as “The Canadian Comic” even though he was a Hoosier born in Vincennes. Hoagy Carmichael was a regular. The standard 1930s Era Lyric theatre contract awarded “Fifty percent (50%) of gross receipts after the first dollar”. Ticket prices in 1936 were defined as: “25 cents to 6 p.m.- 40 cents on the lower floor at night and 30 cents in balcony weekdays, and Saturday. On Sunday, 30 cents in balcony and 40 cents on the lower floor all day.”

The Lyric’s next step towards pop culture immortality came on February 2, 1940, when the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra came to town. Dorsey began his career in a Big Band with his brother Jimmy in the late 1920s. That band also included Glenn Miller. Dorsey had a reputation for being a micromanaging perfectionist with a volatile temper. He often fired musicians based on his mood, only to rehire them a short time later. Dorsey had a well-deserved reputation for raiding other bands for talent. If he admired a vocalist, musician, or arranger, he thought nothing of taking over their contracts and careers.

In November 1939 a relatively unknown “skinny kid with big ears” from Hoboken New Jersey signed on as the lead singer of the Tommy Dorsey band. Frank Sinatra signed a contract with Dorsey for $125 a week at Palmer House in Chicago, where Ole Blue Eyes was appearing with the Harry James orchestra. Mysteriously, but not unsurprisingly, Harry James agreed to release Sinatra from his contract. An event that would come back to haunt Dorsey a couple years later.

Dorsey was a major influence on Sinatra and quickly became a father figure. Sinatra copied Dorsey’s mannerisms and often claimed that he learned breath control from watching Dorsey play trombone. He made Dorsey the godfather of his daughter Nancy in June 1940. Sinatra later said that “The only two people I’ve ever been afraid of are my mother and Tommy Dorsey”.

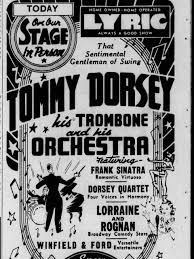

From February 2-8, 1940, when the Dorsey band opened at the Lyric, the theater’s ad in the Indianapolis Star listed Tommy’s name in inch-high letters. At the bottom, in 1/8-inch type, was a listing for “Frank Sinatra, Romantic Virtuoso.” The songs he sang during that week of shows on the eve of World War II are lost to the pages of history. But we do know that Frank Sinatra made eighty recordings in 2 years with the Dorsey band.

By May 1941, Sinatra topped the male singer polls in Billboard and Down Beat magazines, becoming the world’s first “Rock Star”. His appeal to bobby-soxers created “Pop Music” and opened up a whole new market for record companies, which had been marketing primarily to adults up to that time. The phenomenon would become officially known as “Sinatramania”. Manic female fans often wrote Sinatra’s song titles on their clothing, bribed hotel maids for an opportunity to touch his bed, and chased the young star often stealing clothing he was wearing, usually his bow tie.

By 1942, Sinatra believed he needed to go solo, with an insatiable desire to compete with Bing Crosby, his childhood idol. Sinatra grew up with a picture of Crosby in his bedroom, and in 1935 young Frankie met his idol briefly backstage at a Newark club. Within a decade, Sinatra would be contending for Crosby’s throne. A series of appearances at New York’s Paramount Theatre in December 1942 established Sinatra as the hot new star. When Sinatra sang, young girls in the audience swooned, screaming so loud that it drowned out the orchestra. The girls never swooned and screamed when Bing Crosby sang. Sinatra decided early not merely to imitate Crosby, but to develop his own style. In a 1965 article, Sinatra explained: “When I started singing in the mid-1930s everybody was trying to copy the Crosby style — the casual kind of raspy sound in the throat. Bing was on top, and a bunch of us … were trying to break in. It occurred to me that maybe the world didn’t need another Crosby. I decided to experiment a little and come up with something different.”

Frank’s singing evoked frailty, innocence, and vulnerability and inflamed the passions of his young female fans. Some older listeners, however, rejected Sinatra’s gentle sighing, moaning, and cooing as not real singing. Crosby joked: “Frank Sinatra is the kind of singer who comes along once in a lifetime — but why did it have to be my lifetime!”

Sinatra was hamstrung by his contract with the Dorsey band, which gave Dorsey 43% of Frank’s lifetime earnings in the entertainment industry. On September 3, 1942, Dorsey famously bid farewell to Sinatra by telling Frankie, “I hope you fall on your ass”. Rumors began spreading in newspapers that Sinatra’s mobster godfather, Willie Moretti, coerced Dorsey to let Sinatra out of his contract for a few thousand dollars by holding a gun to Tommy’s head and telling him that “either your signature or your brains will be on this contract.” Apparently, Sinatra made him an “offer he could not refuse”. Yes, that famous scene in The Godfather is based on this encounter.

Dorsey died in 1956, but not before telling the press this of his one-time protege, “he’s the most fascinating man in the world, but don’t put your hand in the cage”. Regardless of the way it ended between the duo. It all began at the Lyric Theatre in Indianapolis.

If you are interested in learning more about the Lyric and other legendary Circle City theatres, I highly recommend you read “The Golden Age of Indianapolis Theaters” (IU Press) by Howard Caldwell, former WRTV-Channel 6 anchor and friend of Irvington.

The Lyric Theatre. Part II.

Original Publish Date January 21, 2016. Republished January 23, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2016/01/21/the-lyric-theatre-part-2/

Frank Sinatra’s career began at the Lyric Theatre in Indianapolis on February 2, 1940, with the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra. Sinatra stuck with Dorsey for a couple years before he went solo. Allegedly, Dorsey only let go of Frankie at the gentle urging of Ole Blue Eyes’ Mafia Godfather, who was holding a gun to Dorsey’s head. Dorsey and Sinatra, who had once been very close, never patched up their differences. Ironically, Dorsey had a hand in the Lyric Theatre’s second step towards immortality for the next bobby-soxer generation.

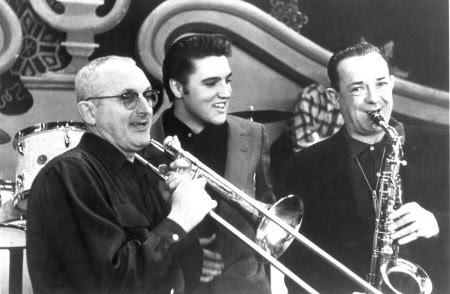

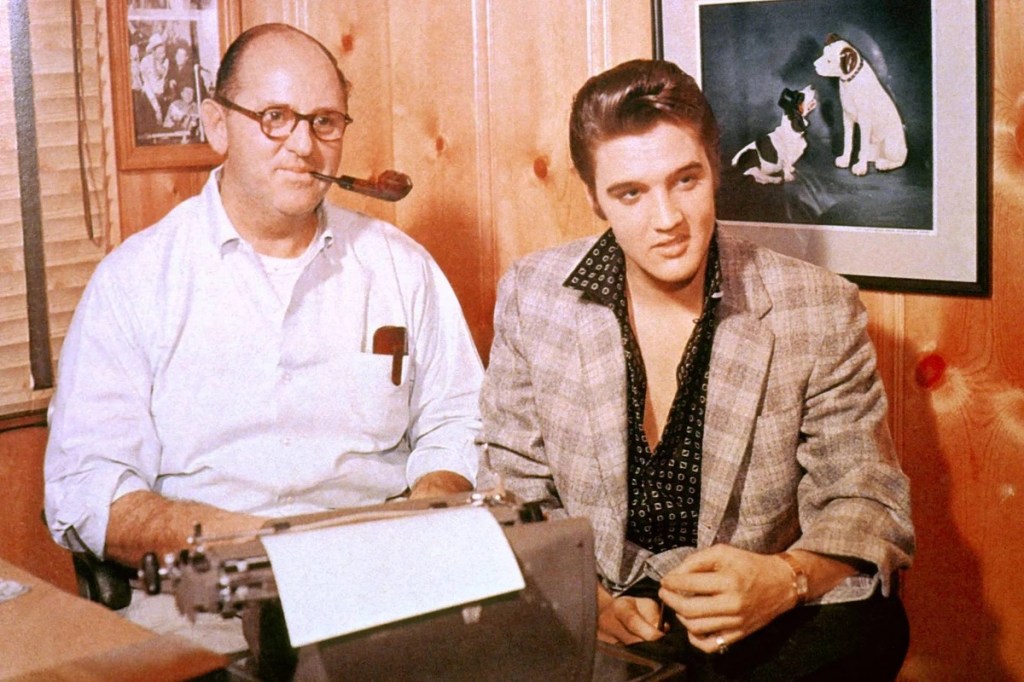

On January 28, 1956, another pop culture icon burst onto the American scene via The Dorsey Brothers TV Show. Tommy Dorsey introduced Cleveland disc jockey Bill Randle, who then introduced Elvis Presley to his first national audience by saying: “We’d like at this time to introduce to you a young fellow who…came out of nowhere to be an overnight big star…We think tonight that he’s going to make television history for you. We’d like you to meet him now – Elvis Presley”. That night the show aired from CBS Studio 50. The same studio that launched the careers of the Beatles, who would themselves eventually dethrone Elvis 8 years later. Years later, Indianapolis Native David Letterman would broadcast his Late Nite show from the same studio- yet another Hoosier pop culture connection.

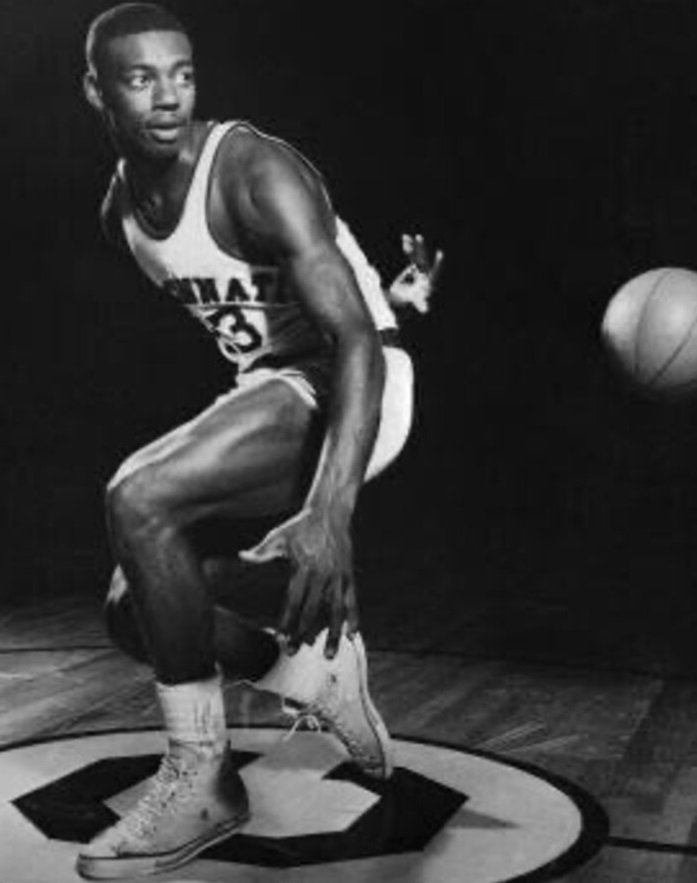

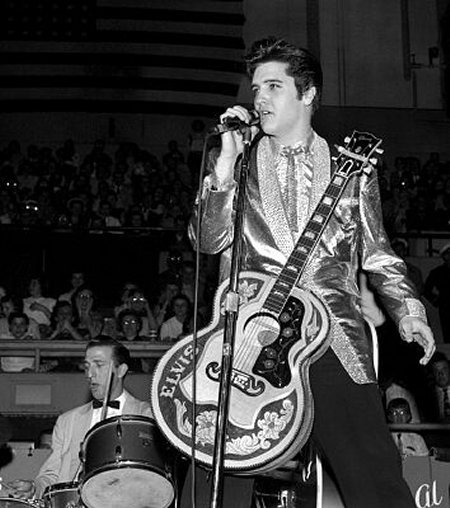

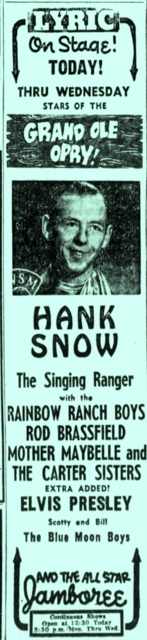

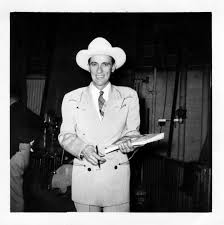

A little more than a month before that national television debut, Elvis Presley played the Lyric theatre for four days: Sunday, December 4th through Wednesday, December 7th. Elvis was paid $ 1,000 for 4 shows. 20-year-old Presley was part of Hank Snow’s tour that played the Lyric, once located in the 100 block of North Illinois Street. Presley, who never received formal music training or learned to read music, studied and played by ear. He also frequented record stores with jukeboxes and listening booths, where he memorized all of Hank Snow’s songs.

Hank Snow was the headliner and his name appeared on the Lyric theatre marquee in giant letters. Snow, a regular at the Grand Ole Opry, persuaded the Opry to allow a young Elvis Presley to appear on stage in 1954. Snow used Presley as his opening act and introduced him to the infamous Colonel Tom Parker. The Opry believed Elvis’ style didn’t fit with their image so they suggested he go the the Louisiana Hayride radio show instead. By the time Elvis came to the Lyric, he was a hayride regular. Seems Elvis’s performance at the Lyric, although one of his first, may have been one of his last without controversy.

In August 1955, Colonel Tom Parker joined Hank Snow’s Attractions management team just as Presley signed his first contract with Snow’s company. Elvis, still a minor, had to have his parents sign the contract on his behalf. Before long, Snow was out and Parker had total control over the rock singer’s career. When Snow asked Parker about the status of their contract with Elvis, Parker told him, “You don’t have any contract with Elvis Presley. Elvis is signed exclusively to the Colonel.” Forty years later, Snow (who died in 1999) stated, “I have worked with several managers over the years and have had respect for them all except one. Tom Parker (he refused to call him the Colonel) was the most egotistical, obnoxious human being I’ve ever had dealings with.”

When Elvis breezed through Indianapolis just before Christmas of 1955, he was young, he was raw, he was pure and he was blonde. Yes, Elvis Presley was a natural blonde. Elvis’s signature jet-black raven hair was actually a dye job courtesy of Miss Clairol 51D and Black Velvet & Mink Brown by Paramount. The future King of Rock ‘n Roll thought that dying his hair black gave him an edgier look. Elvis once confessed to dying his hair with black shoe polish in his earliest days. So who knows? Maybe he was traveling through the Circle City with a can or two of Shinola in his ditty bag back in ’55.

Elvis was accompanied to the Lyric by guitarist Scotty Moore, bass player Bill Black, and drummer D.J. Fontana. The Lyric bill included headliner Hanks Snow, Mother Maybelle, and the Carters and comic Rod Brasfield, for a four-day gig. Black, Moore, and Fontana toured extensively during Presley’s early career. Bill Black played stand-up bass, and his on-stage “clown” persona fueled memorable comedy routines with Presley. Black often performed as an exaggerated hillbilly with blacked-out teeth, straw hat, and overalls. Black’s on-stage personality was a sharp contrast to the introverted, consummate professionalism of veterans Moore and Fontana. The balance fit the group’s Lyric performances perfectly.

The newspaper ads billed Elvis (in very small print face) as “a county and bop singer.” According to a later report in the August 8, 1956, Indianapolis Times, headliner Hank Snow missed the first show (Sunday, December 4th) due to a winter storm. Showing amazing resolve at a very young age, Elvis stood in for his childhood hero and carried on with the supporting acts to perform a seamless show. The original contract called for Elvis to be paid $750 for the four-day engagement, but Elvis was paid an extra $ 250 for saving Snow’s bacon during that first show.

Two weeks later, on December 20th, RCA released Elvis’ four earlier Sun records singles: “That’s All Right”/”Blue Moon of Kentucky,” “Good Rockin’ Tonight”/”I Don’t Care If the Sun Don’t Shine,” “Milkcow Blues Boogie”/”You’re a Heartbreaker,” and “Baby Let’s Play House”/”I’m Left, You’re Right, She’s Gone.” Now the King was off and running. Elvis, Scotty, Bill, and D.J. would only make one other appearance together in the state of Indiana, in Fort Wayne when they performed at the Allen County Memorial Coliseum on Mar 30, 1957. Elvis’ Lyric Theatre band broke up a year later although Fontana, Moore, and Elvis still played and recorded together regularly throughout the 1960s.

After 1958, Bassist Bill Black never played with the band again; he died of a brain tumor on October 21, 1965, at the age of thirty-nine. Moore and Fontana performed together on a 2002 recording of “That’s All Right (Mama)” with ex-Beatle Paul McCartney who performed on the recording using Black’s original stand-up “slap” bass. McCartney received the instrument as a birthday present from his wife Linda in the late 1970s. In the documentary film “In the World Tonight”, McCartney can be seen playing the bass and singing his version of “Heartbreak Hotel”.

But what about the Lyric in the years before and after Elvis burst onto the scene? Well, we know that Sinatra’s idol Bing Crosby played the Lyric way before Ole Blue Eyes or Elvis ever knew the address. We know that Chuck Berry played the Lyric on October 19, 1955, just after signing with Chess Records and recording the classic “Maybelline”. We also know that the Lyric closed briefly on May 24, 1956, for a summer remodel and reopened on August 29, 1956. With the installation of Norelco 70-35 projectors it could now show 70mm film. Continuing the Lyric’s tradition as a pioneer in theatre sound performance (it was the first theater in the city to show a Stereophonic Sound Film, Fantasia in 1942) it was the first in Indianapolis to feature the Todd-AO sound system. A new screen measured 50 feet by 25 feet. The opening film was “Oklahoma” which lasted for six months.

In the sixties, the Lyric was a part of the Indianapolis Amusement group which also included the Circle and Indiana theaters, still standing at the time. On March 31, 1965, the “Sound of Music” opened at the Lyric and ran until January 17, 1967, the longest run for a motion picture at the Lyric. But the glory days of the Lyric were fading fast. Urban flight and suburban relocation led to multiplexes and the death of golden-age theatres like the Lyric. The theatre that helped to introduce pop icons Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley closed in 1969. “Shoes of the Fisherman” and “Where Eagles Dare” were the last two movies shown there. The magnificent movie house, once touted as Indianapolis’ finest theater, located at 135 North Illinois Street is just a memory today, replaced by a parking garage.

Elvis would return to Indianapolis 22 years later to perform his last concert ever before 17,000 adoring fans on June 26, 1977, at Market Square Arena, which was also demolished. Reviews of the show criticized the performance as a “tacky circus sideshow at which the star was sloppy and lethargic”. Like the Lyric, Elvis became a victim of changing times and more sophisticated attitudes. The King died on August 16, 1977, 51 days after his appearance at MSA and 21 years, 8 months, and 12 days after he first strolled into the Lyric theatre to cover for his idol Hank Snow. [The MSA stage that Elvis resides in now rests inside the Irving Theatre in Irvington.]

As for me, I’d prefer to remember Elvis for his trip through Indy’s eastside a year after he played the Lyric. Sometime in late 1956, Presley was reported to have stopped at the Jones and Maley automotive garage, a stone’s throw from Irvington at 3421 E. Washington St., to have the two front whitewall tires on his baby blue Cadillac balanced. According to mechanics working on the vehicle, Presley’s car had girls’ names scratched into the paint. An urban legend has Elvis driving that same Cadillac car on that same day just up the road to Al Green’s for a snack before heading on to a tour stop in Ohio. That, like the image of the Lyric Theatre’s marquee glowing brightly on a Saturday night, is the image I choose to keep with me of the King in Indianapolis.

If you are interested in learning more about the Lyric and other legendary Circle City theatres, I highly recommend you read “The Golden Age of Indianapolis Theaters” (IU Press) by Howard Caldwell, former WRTV-Channel 6 anchor and friend of Irvington.