Original publish date: August 7, 2014

Original publish date: August 7, 2014

On February 19, 2009, demolition crews knocked down the final wall of the 96 room Indianapolis Motor Speedway Motel aka Brickyard Crossing Inn, which was closed by the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in December of 2008. They knocked it down so fast that race fans and historians didn’t have a chance to notice, much less complain, until it was gone. On February 19, 2009, demolition crews knocked down the final wall of the 96 room Indianapolis Motor Speedway Motel aka Brickyard Crossing Inn, which was closed by the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in December of 2008. They knocked it down so fast that race fans and historians didn’t have a chance to notice, much less complain, until it was gone.

The modern style motel opened in 1963 to much fanfare. Located just off of Turn 2 of the legendary 2-1/2-mile oval, at the time, no other racing facility in the country could boast its own motel located on property. The opening of the motel 54 years ago filled a void in lodging on the near-west side of Indianapolis; long before the growth associated with the construction of Interstate 465. The Speedway Motel’s location assured that only the elite of racing stayed in the convenient confines. Some of the greatest names in auto racing history stayed at the motel, not to mention movie stars, politicians, and music legends.

Like the Speedway, the Brickyard Crossing Inn had a famous history. Besides being the home for several Indianapolis 500 drivers, personalities and owners during the month of May, scenes from Paul Newman’s movie “Winning” were filmed in rooms of the motel. Who knows how many 500 race winners have stayed there prior to the days of million-dollar motorhomes? NASCAR legend Jeff Gordon celebrated his win in the 1994 inaugural Allstate 400 at the Brickyard by eating a pizza in his room at the motel. Oh, the stories those rooms could’ve told. Every West sider should remember the distinctive sign out front welcoming fans before the race, and congratulating the winner afterwards.

When the Speedway Motel opened, John F. Kennedy was President, Alcatraz was still a working prison, the Beatles released their first record and there wasn’t another hotel in sight. Today there are 30,000 hotel rooms in the vicinity and the Speedway Motel lost it’s identity in this modern world. Speedway management decided that bringing the old Motel up to modern standards would simply cost too much, so the hotel was closed and its 15 workers were sent home for good. After all, by today’s standards, the IMS Motel wasn’t exactly an architectural masterpiece.

The Speedway Motel’s guest list? It was something else. Just about every celebrity that attended the Indianapolis 500 over the Motel’s 45 year lifetime stayed at the IMS Motel. Names like James Garner, Jim Nabors, Paul Newman and Jayne Mansfield made it their home while in town for the Greatest Spectacle in Racing. At one time or another, nearly every Indy 500 driver lived there during the entire month of May. It was the preferred residence of 4-time Indy 500 winner AJ Foyt. Same is true of car owner Roger Penske, who typically passed on the luxury motor homes and condos for a comfortable room at the motel.

However, by the mid-1980s, the old motel was beginning to show its age. By then, it had taken on the appearance of an old roadside movie motel. Glasses were wrapped in paper sleeves and housekeeping staff still put the strip of paper across the toilet seat that said “Sanitized for your protection.” By the late 1990s, the rooms were dank and musty-smelling, and in the wintertime the rooms were intolerably hot. As the years passed, it became apparent that IMS officials had to come to a decision, the motel had to either be renovated or razed. Nowadays, the only evidence remaining of this once glorious Motel can be found in the memorable scene from the movie “Winning” when Newman’s character, Frank Capua, returned to the motel after leaving Gasoline Alley and catches Joanne Woodward (Ironically Newman’s real life wife) and co-star Robert Wagner “in the act” in Room 212 of the IMS Motel.

Newman was a fixture at the speedway for decades as a car owner for Mario Andretti in the 1980′s. During those years Newman would give his guests tours of the Speedway, he would always point out the room where the film scene took place. Newman recalled in a 2007 interview, “I always used to take a golf cart and drive the sponsors to the back of the Speedway Motel, and I would stop for a minute and point to a room and say, ‘And that’s where my wife shacked up with Robert Wagner,'” Newman continued, “I’d let that comment sit there, and deep silence and embarrassment would fall over everybody. Then 10 minutes later I’d say, ‘Oh, in the movie I meant.'” He made his final appearance at the speedway during qualifications for the 2008 Indianapolis 500, just four months before losing his battle with cancer.

It was renamed the Brickyard Crossing Inn after the race track became home to NASCAR’s Brickyard 400 race in 1994 and for awhile, the motel added NASCAR stars to its famous guest list, including the winner of the Inaugural Brickyard 400 in 1994, Jeff Gordon. After all the pictures, media interviews and celebratory appearances were over, Gordon and his first wife, Brooke, went back to their room at the motel and called Domino’s to order a ham and pineapple pizza. The unsuspecting employee on the other end said, “It’s going to take about two hours to get the pizza delivered because there was a race there today.” to which Gordon responded, “I know. I’m the driver who won the race.” After convincing the Domino’s employee that he was indeed Jeff Gordon, the pizza arrived much sooner than two hours.

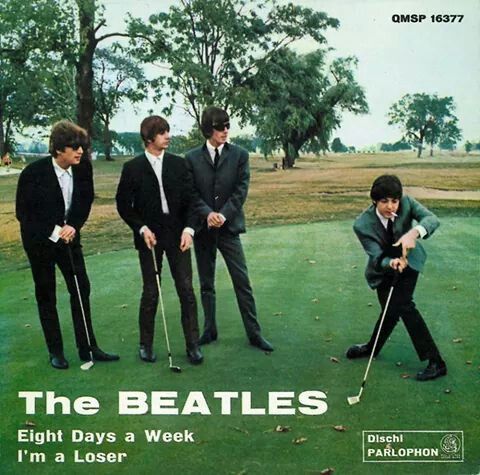

The most famous non-racing related guests to stay at the motel were “The Beatles” who stayed in the Motel during their 1964 tour appearance in Indianapolis. Legend has it that during their stay in Indianapolis, fans were tipped off they were staying downtown at the Essex House Hotel. To mislead frenzied fans who might rush the motel, the Beatles’ managers let it leak out that the “Fab Four” would be staying at the swanky downtown hotel. To further add to the ruse, they put the crew traveling with the Beatles at the Essex.

Their manager then put all four in one room at the IMS Motel. The Beatles enjoyed a quiet refuge there for one weekend in September 1964 while playing two shows at the Indiana State Fairgrounds. That night after the show, the band returned to the Speedway Motel to relax before heading to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the next stop on their franticly-paced 1964 North American Tour. Ringo could not sleep and asked his police escort if they could drive him around the city and grab a late night bite to eat. The policeman in charge took Ringo to a restaurant known as “Charlie’s Steakhouse” on the north edge of Carmel, located at the point where Meridian Street (U.S. highway 31) and Range Line Road (Indiana highway 431) come together. Old timers will remember it as “Ben’s Island”, a bar located within the old Carmel Motel. Ringo had eggs and coffee before returning to the Speedway Motel in the wee hours of the morning. The policeman received a reprimand for this impromptu tour but Ringo later sent a thank-you note to the State trooper and his family for the opportunity to escape the tour for a little while.

The next day, a photographer arrived to snap a few pictures of the Beatles at their Indy Motel. There were pictures of the Fab Four talking with their police escort on the balcony. Photos of the boys playing with remote control slot cars on an oval track set up on the floor of their room. The most famous image from that shoot was that of all four lads playing golf on one of the Speedway golf course greens. Afterwards, the State Police security detail took them for a lap around the track before finally heading for the airport. In the book, “The Beatles Anthology”, George Harrison remembered it this way: “Indianapolis was good. As we were leaving, on the way to the airport, they took us round the Indy circuit….It was fantastic.”

When I found out the motel was going to be torn down, I was hoping to be able to get access to the room for some photo memories to compare to the movie. Life and the Indiana Winter got in the way and delayed my trips to the Motel until I received a phone call from friends Steve and Kim Hunt telling me that, “I’m driving past it and they’re tearing it down right now.”

Thank goodness the old motel’s main building will continue to house its popular restaurant, a conference center, pro shop of the Brickyard Crossing Golf Course and the legendary “Flag Room” pub. All will continue operation. The Flag Room bar remains a popular watering hole with regular patrons whose colorful nicknames like “Tires” and “Jonesy” hearken back to the golden days of Indy motorsports. In May, and especially during race week, The Flag Room is a prime gathering spot for former 500 winners like Jim Rathmann and Parnelli Jones to sit and talk about the good old days of their glorious racing careers. Other drivers, such as Al Unser, Bobby Unser, Johnny Rutherford and Mario Andretti, occasionally stop by for lunch or dinner.

“The motel and the restaurant were places where you could stand any day during May and just see everybody. It would have been an autograph-hunters paradise but I don’t think that word ever really got out,” Davidson said. “Who wouldn’t want to hear the lunch conversation among former Indiana basketball coach Bob Knight, four-time Indy winner A.J. Foyt and Speedway owner Tony George”, Davidson chuckled. “They were golfing buddies.”

The razing of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Motel closed a chapter on a piece of the history of the century old Indy 500 Mile Race. They say that all good things must come to an end, but I can’t help but feel that we lost a symbol of Indianapolis sports and pop culture history with the destruction of the old motel. It was a time when a normal Hoosier kid could venture to West 16th street in the off season to sleep in the same beds as the heroes of their youth…and dream.

Original publish date: May 2, 2017

Original publish date: May 2, 2017 The ABA Indiana Pacers were the powerhouse of the old American Basketball Association, appearing in the league finals five times and winning three Championships in nine-years. By the time of the NBA-ABA merger in 1976, the Pacers had established themselves as the league’s elite. The players were household names and their reputation was now legend. The crowds at the State Fair Coliseum, and later Market Square Arena, where the Pacers held court were always dotted with celebrities from all walks of life. In the Circle City of the seventies, everyone wanted an association with the Pacers. In short, they were rock stars.

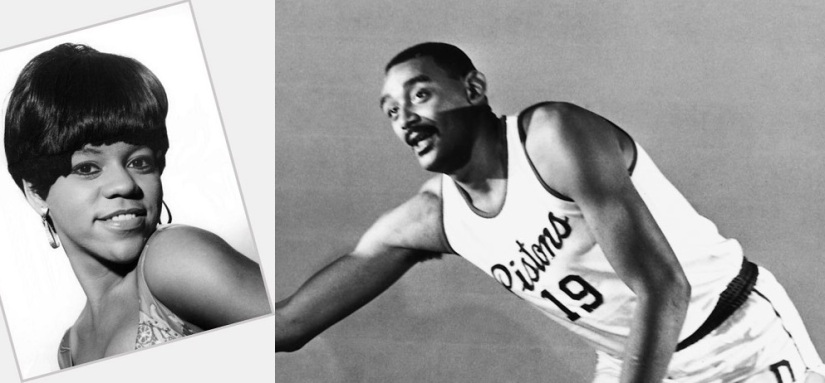

The ABA Indiana Pacers were the powerhouse of the old American Basketball Association, appearing in the league finals five times and winning three Championships in nine-years. By the time of the NBA-ABA merger in 1976, the Pacers had established themselves as the league’s elite. The players were household names and their reputation was now legend. The crowds at the State Fair Coliseum, and later Market Square Arena, where the Pacers held court were always dotted with celebrities from all walks of life. In the Circle City of the seventies, everyone wanted an association with the Pacers. In short, they were rock stars. Young Marvin, who would grow to be over 6 feet tall, became a fixture on the tough D.C. basketball courts. One of his neighbors was future Detroit Mayor and Pistons All-star Dave Bing. Although smaller and four years younger, Bing played alongside Gaye on those DC project courts. The two men forged a friendship that lasted the rest of their lives. Bing continued to excel on the court as Marvin’s skills faded. Ironically, both men landed in Detroit. Gaye turned to song, which led him to Motown immortality; Bing landed in the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Young Marvin, who would grow to be over 6 feet tall, became a fixture on the tough D.C. basketball courts. One of his neighbors was future Detroit Mayor and Pistons All-star Dave Bing. Although smaller and four years younger, Bing played alongside Gaye on those DC project courts. The two men forged a friendship that lasted the rest of their lives. Bing continued to excel on the court as Marvin’s skills faded. Ironically, both men landed in Detroit. Gaye turned to song, which led him to Motown immortality; Bing landed in the Basketball Hall of Fame. While Marvin was busy helping Berry Gordy shape the sound of Motown in the 1960s, he never lost his love of sports. The “Prince of Soul” recorded iconic concept albums including What’s Going On and Let’s Get It On while keeping active on the courts, courses and fields around the Motor City. In the book “Divided Soul; The Life of Marvin Gaye”, author David Ritz says, “Gaye was a good athlete, but not of professional quality. His football playing, just like his basketball playing (where he loved to hog the ball and shoot) were further examples of his delusions of grandeur.” Gaye was a regular at celebrity golf tournaments and loved rubbing elbows with pro athletes like Bob Lanier, Gordie Howe and Willie Horton.

While Marvin was busy helping Berry Gordy shape the sound of Motown in the 1960s, he never lost his love of sports. The “Prince of Soul” recorded iconic concept albums including What’s Going On and Let’s Get It On while keeping active on the courts, courses and fields around the Motor City. In the book “Divided Soul; The Life of Marvin Gaye”, author David Ritz says, “Gaye was a good athlete, but not of professional quality. His football playing, just like his basketball playing (where he loved to hog the ball and shoot) were further examples of his delusions of grandeur.” Gaye was a regular at celebrity golf tournaments and loved rubbing elbows with pro athletes like Bob Lanier, Gordie Howe and Willie Horton. Original publish date: March 19 2017

Original publish date: March 19 2017 Original publish date: March 12, 2017

Original publish date: March 12, 2017 Original publish date: August 24, 2015

Original publish date: August 24, 2015 Babe and Claire left shortly after the picture started and checked into Memorial Hospital for the last time. Babe Ruth struggled to answer letters and meet with visitors right up until August 15, 1948, barely a year after he graced the diamond of Victory Field in Indianapolis. Babe Ruth died in his sleep at 8:01 p.m. on the evening of on Aug. 16,1948. His last conscious act was to autograph a copy of his autobiography for one of his nurses. It was only after the great man’s death that the newspapers announced the cause of death as “throat cancer”.

Babe and Claire left shortly after the picture started and checked into Memorial Hospital for the last time. Babe Ruth struggled to answer letters and meet with visitors right up until August 15, 1948, barely a year after he graced the diamond of Victory Field in Indianapolis. Babe Ruth died in his sleep at 8:01 p.m. on the evening of on Aug. 16,1948. His last conscious act was to autograph a copy of his autobiography for one of his nurses. It was only after the great man’s death that the newspapers announced the cause of death as “throat cancer”.