Original publish date: June 26, 2014

Original publish date: June 26, 2014

Editor’s note: Columnist Al Hunter will join author Ray Boomhower on Nelson Price’s “Hoosier History Live!” radio show on WICR-FM (88.7) this Saturday July 5th (2014) at noon. The topic of the show will be Presidential visits to Indiana.

Teddy Roosevelt was in a tight spot in 1902. Barely a year after being catapulted into the Presidency by the assassination of William McKinley at the Buffalo, New York Pan-American Expo on September 6, 1901, T.R. was facing a revolt in his own party. Midwest Republicans were challenging the GOP on their position with tariffs, monopolistic practices and isolationism. Teddy, at the suggestion of his closest advisers, decided to make an eighteen-day tour of the Heartland to quell the uprising with a series of major speeches. After an early September east coast swing, President Roosevelt once again boarded his private train car “Columbia” for a trip to Ohio, Michigan and Indiana.

On September 3, 1902, while on a scheduled stop in Pittsfield, Massachusetts for a speech, T.R. decided that it was a beautiful day for a carriage ride to see the town. Teddy boarded a landau carriage along with Massachusetts governor Winthrop M. Crane and his private secretary George B. Cortelyou. An FBI agent, William Craig, was driving the team of horses. As in most American cities, a streetcar track ran straight down the middle of the street. Agent Craig carefully steered the President’s open-top carriage alongside the track. The trolleys had been ordered not to run that morning to ensure the safety of the town’s most famous visitor.

Suddenly, as the carriage topped Howard’s Hill, a screeching sound was heard behind them. Great God! A trolley was seen wildly careening down the hill towards them. In a flash, it slammed into the carriage, throwing the president and his secretary out and onto the street’s grassy berm. The President’s face was bloodied and his leg injured, but in true Roosevelt style, T.R. brushed off his own injuries and rushed to the aid of his horribly injured bodyguard. But it was too late, FBI agent Craig was crushed to death under the wheels of the electric streetcar.

Suddenly, as the carriage topped Howard’s Hill, a screeching sound was heard behind them. Great God! A trolley was seen wildly careening down the hill towards them. In a flash, it slammed into the carriage, throwing the president and his secretary out and onto the street’s grassy berm. The President’s face was bloodied and his leg injured, but in true Roosevelt style, T.R. brushed off his own injuries and rushed to the aid of his horribly injured bodyguard. But it was too late, FBI agent Craig was crushed to death under the wheels of the electric streetcar.

The fair-haired, blue-eyed Craig was born in Scotland in November 1855. Standing 6 foot 4, weighing 260 pounds, he was a giant of man. He spent 12 years in the British military before moving to Chicago’s South Side and joining the Secret Service in 1900. He was a favorite of Teddy Roosevelt. The President said: “The man who was killed was one of whom I was fond and whom I greatly prized for his loyalty and faithfulness.” William Craig was the first agent of the United States Secret Service killed in the line of duty. Officials declared that if the trolley had hit the carriage just two inches to the right the president and his secretary would also have died.

The accident was never explained. Rumor was that passengers on the trolley paid the driver to follow the carriage in hopes of glimpsing the Rough Rider himself. Still others speculated that it was another Presidential assassination attempt. The driver of the trolley was sent to jail for six months. The President continued his trip and was able to keep his speaking engagements over the next few days. The now lame President stood and shook hands at a pace of fifty-two hands per minute for three hours at a time at most of these engagements. All the while, Teddy’s leg silently throbbed with pain.

The accident was never explained. Rumor was that passengers on the trolley paid the driver to follow the carriage in hopes of glimpsing the Rough Rider himself. Still others speculated that it was another Presidential assassination attempt. The driver of the trolley was sent to jail for six months. The President continued his trip and was able to keep his speaking engagements over the next few days. The now lame President stood and shook hands at a pace of fifty-two hands per minute for three hours at a time at most of these engagements. All the while, Teddy’s leg silently throbbed with pain.

The train left New York on September 20 for his eighteen day speaking tour of the Midwest. At his first stop in Cincinnati, T.R. delivered his planned speech but found that standing was becoming a problem. From Cincinnati the presidential entourage departed for Detroit. Here Roosevelt began quietly complaining about pain in his left leg. The first public indication that there might be something amiss came when T.R. was uncharacteristically unresponsive to questions from the Detroit press pool about the Anthracite Coal strike. He abruptly left the impromptu press conference, retired to the Hotel Cadillac and went to bed.

The next day, he attended a reunion of Spanish American War vets in that city. Although this was Teddy’s forte and these were “his” people, he arrived late and gave a short, labored speech. Instead of his trademark toothy grin, The President grimaced, gasped for breath between sentences and sweated profusely. After his brief address, Teddy stood for 4 hours as the parade of old veterans slowly passed in front of the reviewing stand. By the time the parade ended, Teddy Roosevelt looked like he had been “rode hard and put up wet.”

By the time of his first stop in Indiana, on Tuesday September 23rd, it was apparent that something was wrong with the trust busting chief executive. It was pouring rain as Teddy addressed the crowd in Logansport with a speech he had planned to deliver in Indianapolis. This speech was supposed to change the position of the presidency on national issues. The town had prepared for the Presidential visit by erecting a large platform at the corner of Seventh and Broadway in front of the High School (today aptly known as the “Roosevelt Building”). At the depot, the Elks Band was waiting to lead the procession of carriages for the special guests’ trip to the courthouse. As the parade moved up Market to Ninth Street, the skies opened and it started to rain. A local skating rink had been decorated as an alternate place for Roosevelt to speak, but Teddy insisted on speaking in the rain.

By the time of his first stop in Indiana, on Tuesday September 23rd, it was apparent that something was wrong with the trust busting chief executive. It was pouring rain as Teddy addressed the crowd in Logansport with a speech he had planned to deliver in Indianapolis. This speech was supposed to change the position of the presidency on national issues. The town had prepared for the Presidential visit by erecting a large platform at the corner of Seventh and Broadway in front of the High School (today aptly known as the “Roosevelt Building”). At the depot, the Elks Band was waiting to lead the procession of carriages for the special guests’ trip to the courthouse. As the parade moved up Market to Ninth Street, the skies opened and it started to rain. A local skating rink had been decorated as an alternate place for Roosevelt to speak, but Teddy insisted on speaking in the rain.

The crowd of 5,000 enthusiastically cheered their speaker as he took the stand. T.R. looked out across the sea of umbrellas and announced that he could speak in the rain only if the crowd would put their umbrellas down to hear him. The umbrellas were sheathed and Teddy presented his twenty-seven minute speech outlining the issues that troubled his administration. It seemed as though every policeman in Cass County was present and surrounding the stage, watching the crowd intently. Teddy hushed the adoring masses by imploring his countrymen that “Beneficiaries of the new prosperity must look to themselves, rather than government, for the advancement of their welfare.” Teddy Roosevelt, perhaps the most “individual” President this country has ever seen, stressed the word “individual” again and again in his speech. To the rousing cheers of the gathered crowd, Roosevelt awkwardly limped back into the train for the journey to Indianapolis.

The Logansport stop must have recharged Roosevelt’s batteries as the train made a stop in Tipton where Teddy addressed another adoring crowd on the courthouse square. Next came Noblesville, where 6000 people packed the courthouse lawn to hear the young lion speak. Keep in mind the population of Noblesville was less than 4,000 people at the time. Here, Roosevelt told the crowd “We war not on industrial organizations, but on the evil in them.”

The Logansport stop must have recharged Roosevelt’s batteries as the train made a stop in Tipton where Teddy addressed another adoring crowd on the courthouse square. Next came Noblesville, where 6000 people packed the courthouse lawn to hear the young lion speak. Keep in mind the population of Noblesville was less than 4,000 people at the time. Here, Roosevelt told the crowd “We war not on industrial organizations, but on the evil in them.”

Immediately after the Noblesville speech, Roosevelt had to be assisted down off the stage onto the street as by now he was having a tough time walking. From here, the schedule called for speeches at the Columbia Club and Tomlinson Hall in Indianapolis. Telegrams were sent from the Noblesville train Station to the Columbia Club on Monument Circle stating that the president was ill. Four surgeons were waiting to check the president before he stepped out to greet the Indianapolis crowd. T.R. struggled through a few comments to the enthusiastic crowd but it was apparent that something was quite wrong. His impromptu remarks were cut short as aides rushed Teddy out to a carriage that rushed him to St. Vincent’s Hospital.

Upon arriving at the hospital, Roosevelt refused any anesthetic for the operation on his infected leg. He joked good naturedly with the surgeons “Gentlemen, you are formal! I see you have your gloves on!” T.R. removed his left shoe and his pants, revealing a golfball sized lump three quarters of the way down his shin. As he lay down on the operating table, Teddy remarked, “I guess I can stand the pain.” The attending surgeon picked, cut and scraped at the lump until the infection slowly began to ooze forth. As the doctor went deep inside the pustule, Roosevelt groaned lowly and asked for a glass of water. It took three separate aspirations before the wound was completely cleaned.

At five o’clock Cortelyou issued a statement that the operation was a success and that the President was now resting comfortably with his leg in a sling. At 7:30, a heavily sedated Theodore Roosevelt was carried out of the hospital, lying stiff on a stretcher, his ashen face shining in the glare of the streetlamps. Hoosiers, gathered on the sidewalks outside of the hospital, removed their hats as the President passed. At 8 pm, the Presidential Train left for Washington. The rest of his trip was cancelled. The fear of blood poisoning, although minimized by White House officials, was a very real concern. Later, Roosevelt had another operation to reopen the wound and scrape the bone to remove any infection. Once again, T.R. insisted that no anesthetic be administered. Yep, Theodore Roosevelt was one tough fellow and he proved it right here in Indianapolis.

Original publish date: November 1, 2013

Original publish date: November 1, 2013 Original publish date: October 20 2013

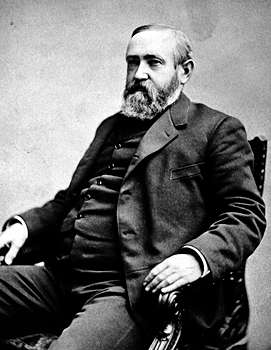

Original publish date: October 20 2013 After the war, Benjamin Harrison spent the next decade practicing law and getting involved in politics. He ran for governor of Indiana in 1876, but lost. The Harrison home on North Delaware Street was built in 1874-75, and soon became a center of political activity. Her husband’s election to the Senate in 1880 brought Caroline to Washington, DC, but a serious fall on an icy sidewalk that year undermined her health. In 1883, she had surgery in New York that required a lengthy period of recovery. She had also suffered from respiratory problems since a bout with pneumonia in her youth, and did not participate much in Washington’s winter social season.

After the war, Benjamin Harrison spent the next decade practicing law and getting involved in politics. He ran for governor of Indiana in 1876, but lost. The Harrison home on North Delaware Street was built in 1874-75, and soon became a center of political activity. Her husband’s election to the Senate in 1880 brought Caroline to Washington, DC, but a serious fall on an icy sidewalk that year undermined her health. In 1883, she had surgery in New York that required a lengthy period of recovery. She had also suffered from respiratory problems since a bout with pneumonia in her youth, and did not participate much in Washington’s winter social season. The First Lady was noted for her elegant White House receptions and dinners, but she is most remembered for her efforts to refurbish the dilapidated White House. She was horrified at the filth and clutter and thought the White House was beneath the dignity of the Presidency, describing it as “rat-infested and filthy.” She brought in ferrets to eat the rats, and lobbied to have the White House torn down and replaced with a more regal Executive Mansion. Instead the old building was refurbished from basement to attic, including a new heating system and a second bathroom. The old, sagging worn-out floors were replaced.

The First Lady was noted for her elegant White House receptions and dinners, but she is most remembered for her efforts to refurbish the dilapidated White House. She was horrified at the filth and clutter and thought the White House was beneath the dignity of the Presidency, describing it as “rat-infested and filthy.” She brought in ferrets to eat the rats, and lobbied to have the White House torn down and replaced with a more regal Executive Mansion. Instead the old building was refurbished from basement to attic, including a new heating system and a second bathroom. The old, sagging worn-out floors were replaced. Original publish date: November 19, 2008

Original publish date: November 19, 2008 Original publish date: June 7, 2013

Original publish date: June 7, 2013