Original Publish Date: August 21, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/08/21/rhonda-hunters-cancer-journey/

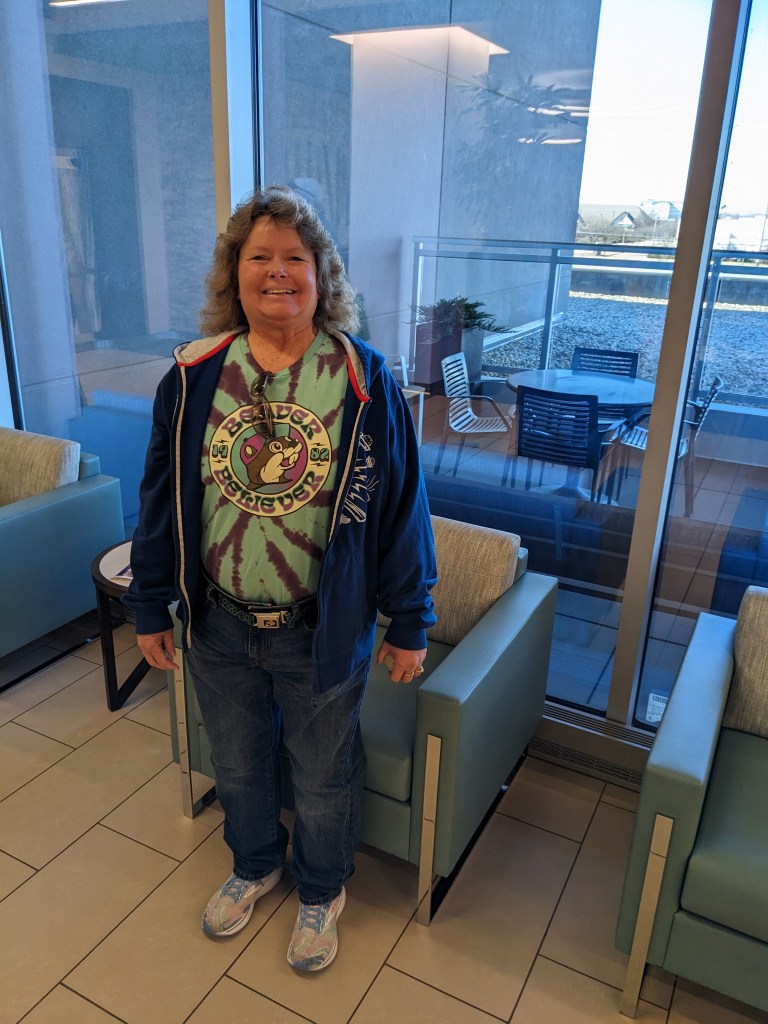

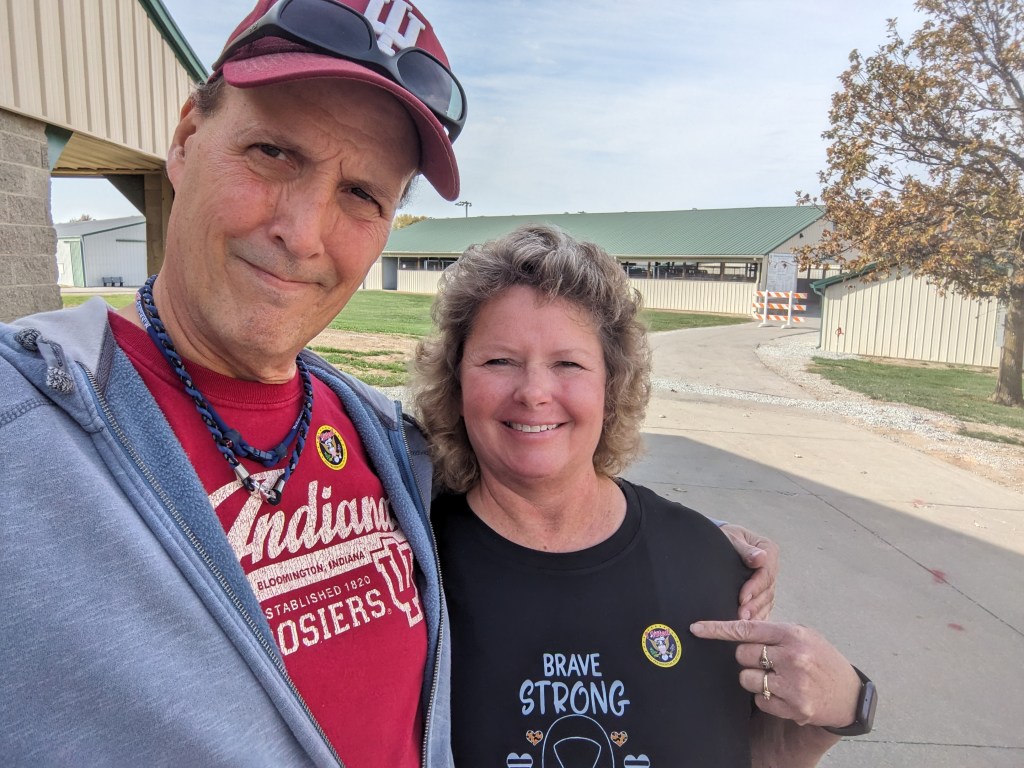

Warning. This is a self-serving article about my hero (my wife, Rhonda) and her year-and-a-half-long cancer ordeal. During our 2023 Irvington ghost tour season, she discovered a bad spot on one of the toes on her left foot. The ring toe to be specific (the little piggy that got no roast beef). At first, she thought it was a bad case of athlete’s foot. Rhonda called around the Indy area searching for a dermatologist: no openings anywhere until Christmas. She found her savior in the form of Megan Rahn, nurse practitioner at Pinnacle Dermatology in Crawfordsville, Ind. Within two days, they got her in and diagnosed it as one of the worst cases of melanoma they had ever seen. Rhonda recalls, “Megan asked if I wanted her to tell me the truth. I said, yes, and she said, ‘It’s cancer.'” We got that news on the Friday of Halloween festival weekend. Rhonda recalls, “During that weekend, longtime regular tour guests kept coming up to me and asking, ‘What’s the matter with Al? He’s not himself tonight.’ Needless to say, it was a rough weekend.

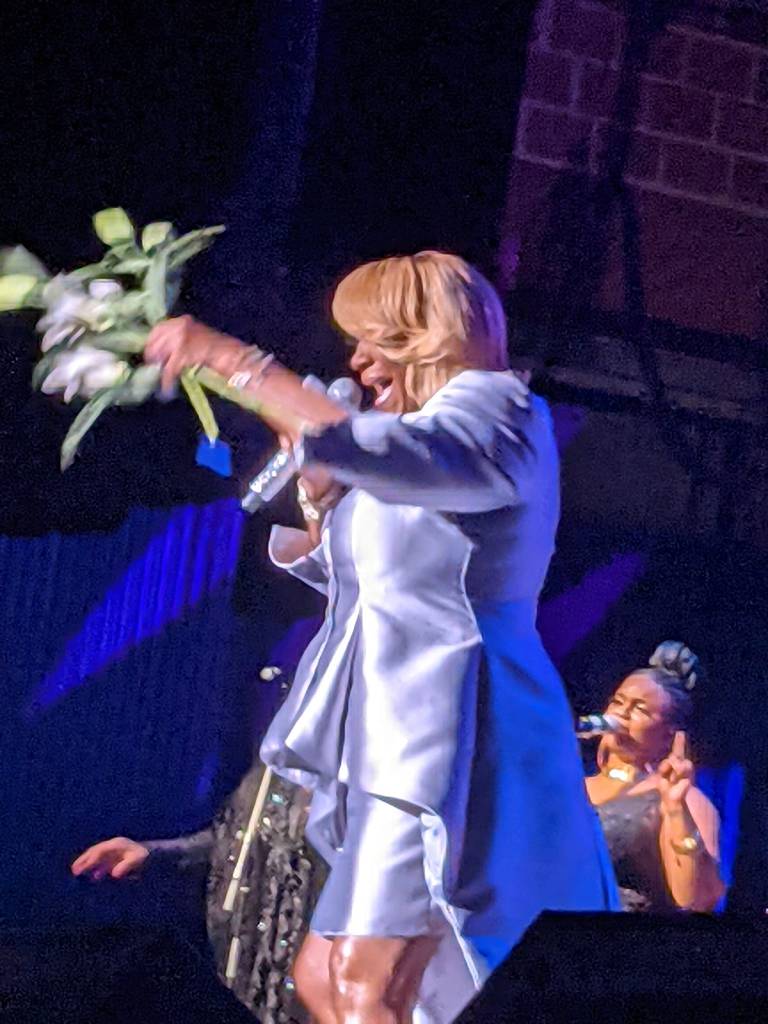

After the tours concluded, we traveled down to our little Ricky and Lucy Ricardo efficiency time share in Daytona Beach, Florida, a luxury we bought ourselves over thirty years ago when we didn’t have two nickels to rub together. Over the years, we discovered that soaking anything in salt water cured almost everything. But this time, it didn’t work. Our trip concluded with a live concert by Patti LaBelle. At the end of the show, Patti walked over to Rhonda and handed her a bouquet of white lilies from a vase on her piano. Traditionally, white lilies symbolize purity and rebirth. Little did we know, it was an omen.

Returning to Indiana, we learned that the good folks at Pinnacle Dermatology had secured an appointment with Dr. Jeffrey Wagner, melanoma reconstruction surgeon at MD Anderson Cancer Center Community North in Indy. By now, the toe was black. Dr. Wagner, who has seen over 20,000 melanoma cases in his decades-long career, said the toe’s gotta go. Her skin cancer was now categorized as a very aggressive form of malignant melanoma, the fastest spreading of all cancers (it can spread to dangerous levels in a month). She went under the knife, and they removed the toe and carved out three more spots, two on the top of her foot and one deep patch on the back of her calf.

They also removed a leaking Lymph Node in the groin. The result was two months in bed and a very uncomfortable Christmas season. We quickly learned that being diagnosed with melanoma is not unlike being an alcoholic, a drug addict, a diabetic, or bipolar: it’s a life sentence. It means a lifetime of treatment, scans, and medical supervision. We are now regulars at Pinnacle Dermatology, where we discovered that more than a few folks from Irvington are regulars. They now refer to Rhonda as “the lady with the toe.”

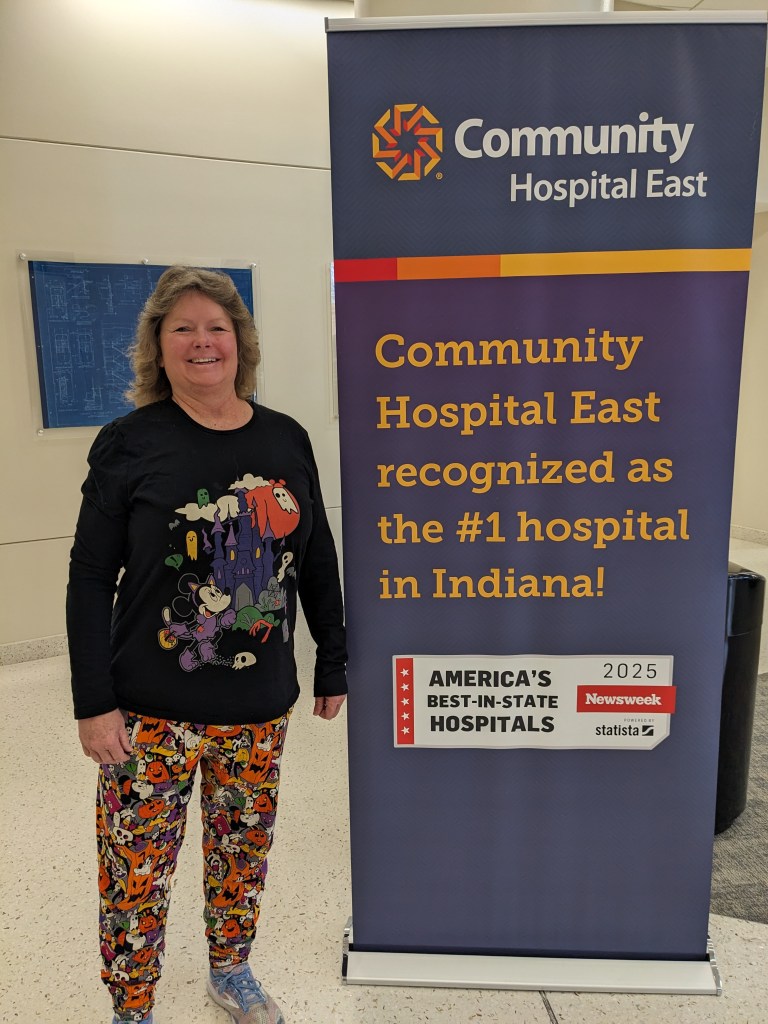

As pilgrims on this journey, we quickly learned that everyone has a skin cancer story. And, sadly, because of that, skin cancer is often minimized as a passing ailment that elicits a dismissive rejoinder. In our case, nothing could be further from the truth. Once everything was removed, we thought that was the end of it. That is, until we learned that a leaking Lymph Node had been detected and Rhonda needed to see Oncologist Dr. Sumeet Bhatia at MD Anderson. Coming a mere three days before Christmas, this was a devastating surprise; Rhonda wasn’t even out of a wheelchair yet. She was placed on Keytruda, a relatively new medicine used to treat melanoma. These monthly treatments, administered intravenously, were accompanied by endless blood work (that alone will make most readers cringe), and regular scans: PET Scans, CT scans, and MRIs. For all of 2024, we became accustomed to bi-weekly visits to MD Anderson, Community North, and Community East.

Sometimes with Oncology nurse Jennifer Chapman, sometimes with cancer navigator & advocate Andrea Oliver, and sometimes with Dr. Bhatia. As her last treatment concluded, we expected to walk out and ring the cancer-free bell. Suddenly, the treatment room door swung open, and in walked her entire team. The melanoma had now spread to her brain. Game changer.

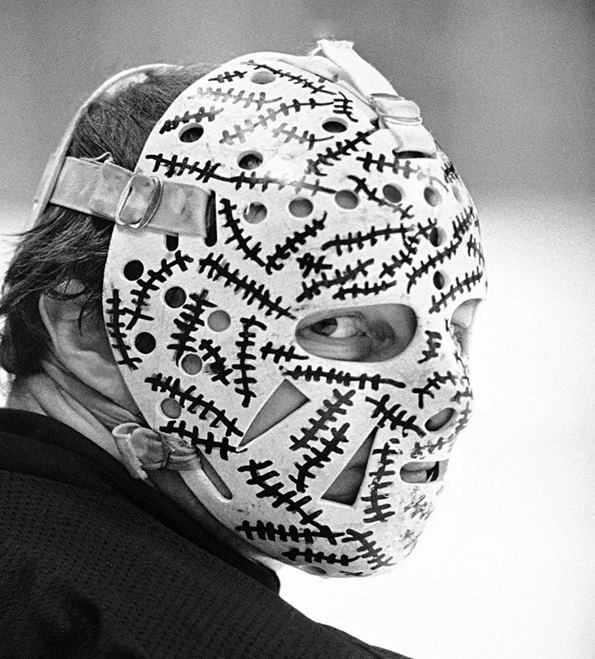

Within moments, the nurse was crying, the advocate was crying, Rhonda was crying, and the doctor was crying. Surprisingly, the only person not crying was me, which is odd, because I’m the guy who tears up at Bambi, Old Yeller, and Steve Hartman stories. The doctor told us he’d give us time to decide whether we wanted to continue with a new treatment, with the warning not to wait too long because it could be too late. I had only two questions: Are they going to cut her and will she lose her hair? The answer was no. Long story short, our 10:30 checkup turned out to be an 11:30 fitting for a Radiation Therapy Thermoplastic Mask. Whenever I saw that mask, I couldn’t help but think of Boston Bruins goalie Gerry Cheevers. Google his mask and you’ll see what I mean.

Within 1 week, she underwent radiology for one spot on the brain. I expected her to be zapped (pardon the pun) of energy and looking for a long nap. Instead, she came bouncing off that table and insisted on heading to Jockamos Pizza and Midland Antiques Market for the afternoon. A few months later, after another MRI discovered she had three more spots on the brain, she underwent another radiation treatment. This time, she had to be helped off the table and out the door. It was a long procedure extending past regular business hours. I was eerily alone in the cancer center and managed to lock myself out of the office, but that’s another story. She still came out smiling, though.

Early summer 2025 was rough as we nervously anticipated a four-month wait for new scan results. Faith & Begorra, the scans were clear! There were other challenges, including an emergency weekend hospitalization for internal bleeding, but it was not cancer-related. Now you know the details of one person’s cancer journey from an observer’s viewpoint. But how about the patient’s view?

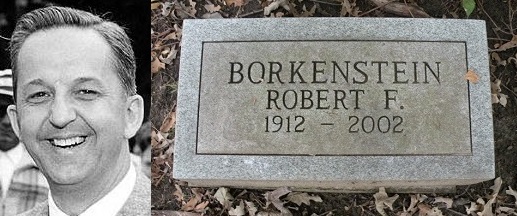

“This is the same cancer that killed Bob Marley, and it started on his toe. It got Jimmy Buffett, too. Jimmy Carter was diagnosed with melanoma on his head and neck at the age of 90 in 2015. It spread to his brain, but after a year of treatment, the spots disappeared.

He died last year at the age of 100, but he didn’t die of melanoma; he died from bleeding in the brain caused by falls.” Rhonda says. “If you get skin cancer, take it seriously. And above all else, stay out of tanning beds. Tanning beds have been labeled as “carcinogenic to humans” by both the World Health Organization and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). So, if you must have those tan lines, spray tanning is safer. Or, just rock that Disney Princess skin!”

My wife is a Disco girl and a creature of the eighties (No lie: her office has a mirrored disco ball, movie posters from Grease and Saturday Night Fever, and a velvet painting of Donna Summer). Like most young people of that era, especially girls, she spent a lot of time (and no little money) in tanning beds.

When I point out that I doubt Marley, Buffett, or Carter ever saw a tanning bed their entire lives, she answers, “Very true. Proof that the sun can damage you, too. Additionally, IARC studies show that if you’ve ever had a severe sunburn before the age of 18, you are 60% more likely to have melanoma, and that tanning-bed use before the age of 35 drives up the risk of melanoma by 75%. Worse, 70% of all melanoma travels to the brain. I never knew how aggressive this type of cancer was until I got it. Back then, not only were there tanning huts in every strip mall, but people of our generation remember using baby oil, cocoa butter, and tanning oil with no SPF whatsoever, straight up turkey basting! Even with all the bad publicity about the dangers of tanning bed use over the past quarter century, the Journal of the American Medical Association reports that 30% of white, female high school students and women ages 18 to 34 have used a tanning bed in the past year.”

I asked Rhonda to retrace her cancer journey, both highs and lows. She answered, “The lows are pretty much what you would expect: fear, discomfort, and pain. I never smoked. I never did drugs, not even when they were prescribed to me. I don’t drink, so I went through a “Why me?” phase. But you get over all that in time. As for the medications, I did very well on Keytruda for the year I was on it. I was worried about it since I’d heard stories about people doing poorly on it and lasting for only one or two treatments. The Keytruda worked on my body, but not on my brain. So they switched my medication twice. They put me on Opdivo and Yervoy for two months (Jan.-Feb.), but it kicked my tail. I lost feeling in my hands and feet and experienced shortness of breath, flu-like pain all over, and I couldn’t even walk up a short flight of stairs.

They put me on steroids, which alleviated the pain but pumped me up like the Michelin Man. They weaned me off of them slowly, but it came with an unfortunate side effect. I was tired all the time, with abdominal pain, muscle soreness, nausea, and vomiting. Worse, when I quit steroids, I went through wicked withdrawals; I was dope sick, like an addict. It’s starting to go away, but now the pain and discomfort are coming back. I am now on Braftovi and Mektovi. It makes me nauseous, weak, and tired. I don’t have many good days anymore, and even the good days aren’t great (It hurts to brush my hair). But I know there are many patients in much worse shape than me, so I’m going to keep fighting.”

“I have been blessed with friends and family who love and support me. The value of those connections can’t be understated. My mom, Kathy Hudson, has been there from the beginning; diagnosis, treatment, and home-care. My dad, Ron Musick, has been a constant support, both by phone and in person. My children, Jasmine and Addison, have been better than I ever could have imagined. Addison, my mom, and you were the first faces I saw coming out of surgery. Jasmine, a former IU Med student, has made researching melanoma her new hobby. She discovered a web community on Reddit called “Melahomies” which has been quite helpful and informative. My sister Rennee, who works in the medical industry, has been a fountain of youth and support from Florida. I am equally blessed to have friends to lean on as well.

Thanks to Becky Hodson, Kris Branch, Cindy Adkins, Tim Poynter, Karen Newton, Kathleen Kelly, and Jodie Hall for being there. I am grateful for the continued support of Irvingtonians like Jan and Michelle at the Magick Candle, Adam and Carter at Hampton Designs, Dale Harkins at the Irving Theatre, and, of course, the girls at the Weekly View. Not to mention the support of your friends in the historic field. Barb Adams, Bruce & Deb Vanisacker, our Gettysburg friends and friends in the Lincoln community: Doc Temple (who passed earlier this year), Dr. James Cornelius, Bill and Teena Groves, and Richard Sloan. People like them rarely get the praise they deserve. If you ever find yourself in my position, or any traumatic medical condition for that matter, don’t be afraid to lean on your friends and family. They are as important to your healing process as the doctors and nurses. And of course, you Al, you are my rock.”

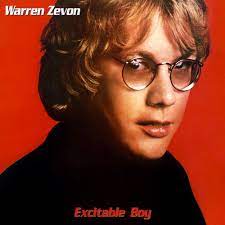

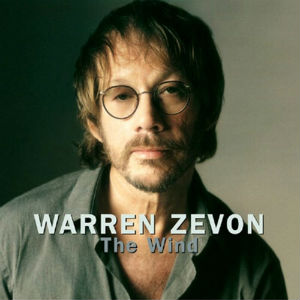

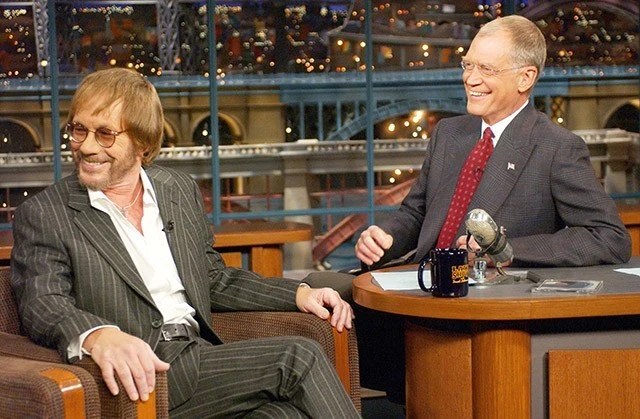

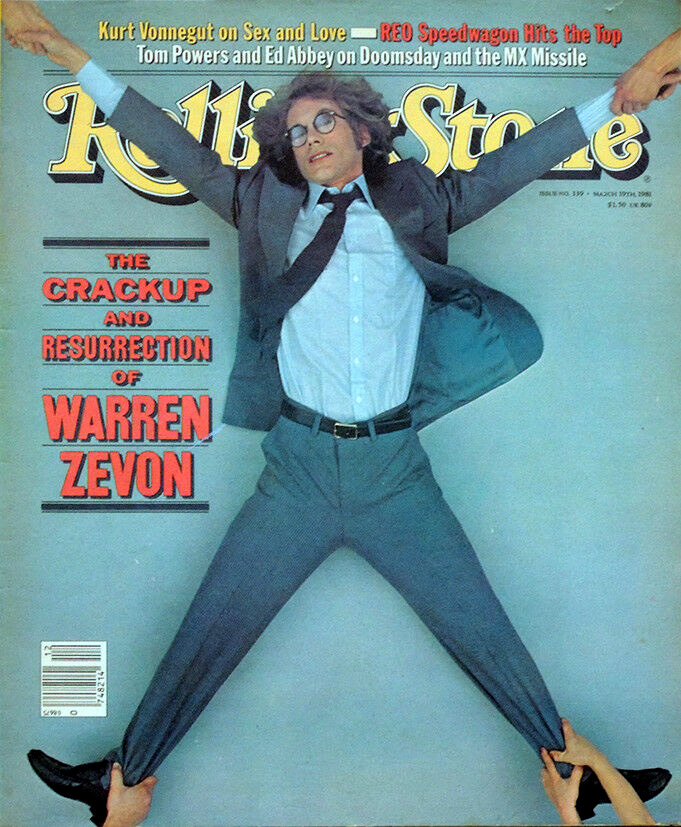

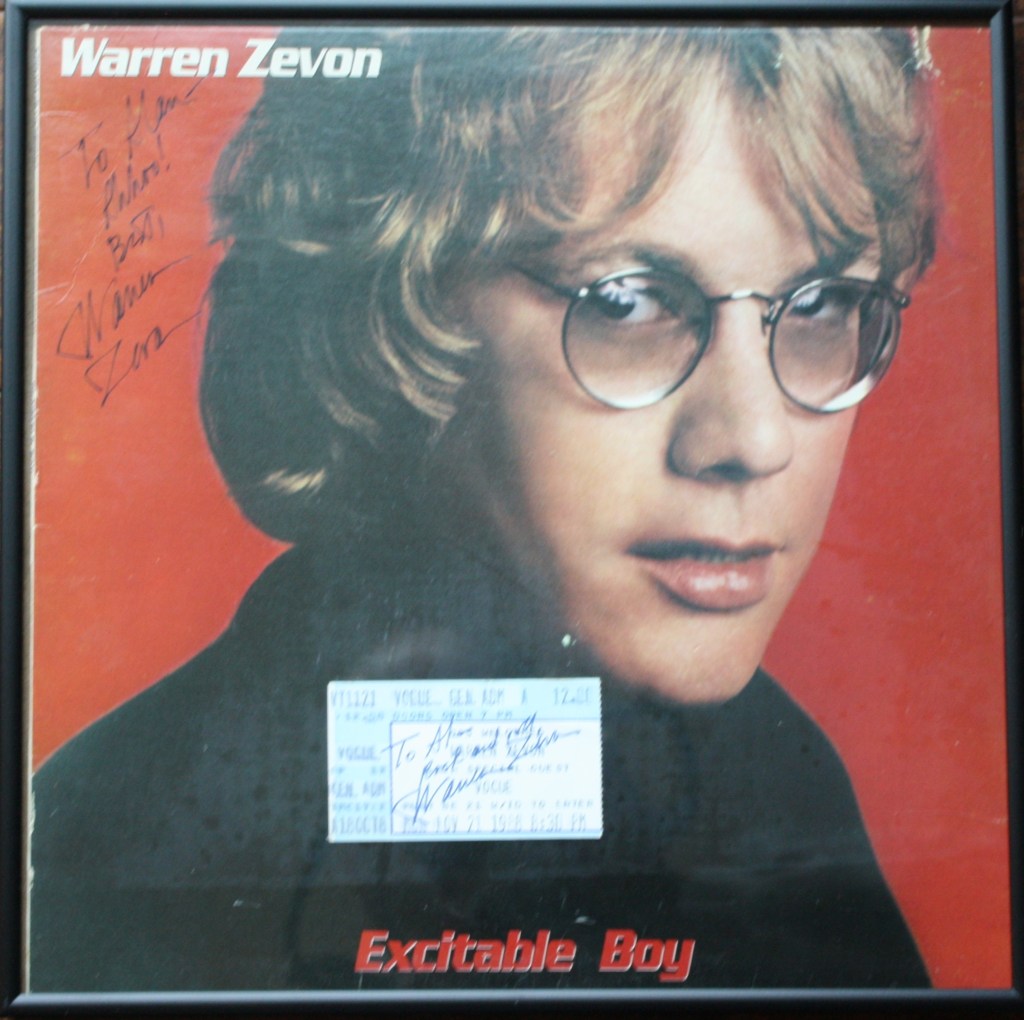

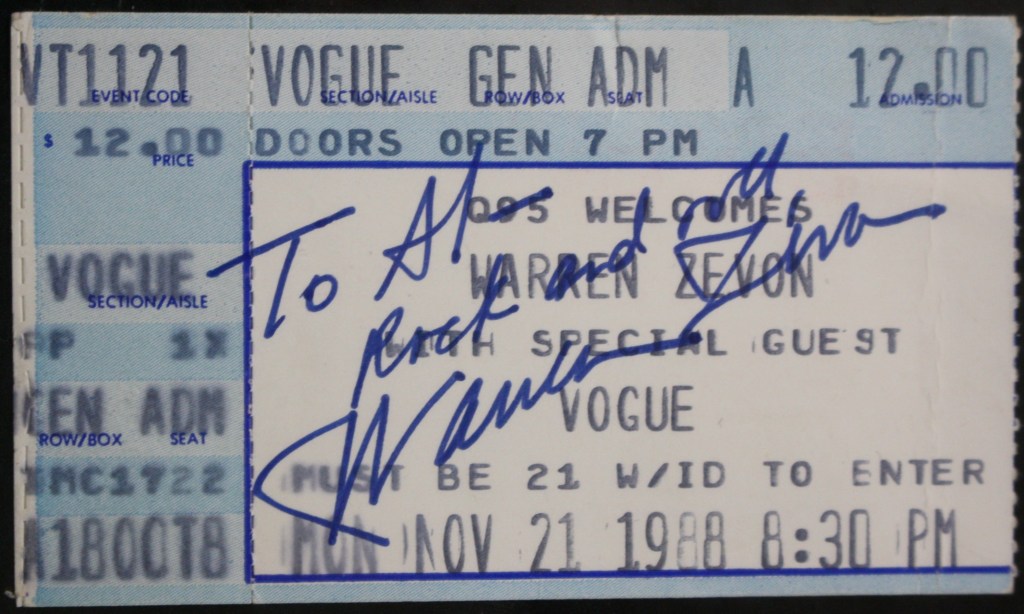

My first introduction to skin cancer came from our longtime friend, former ABA Pacers legend Bob Netolicky, and his family in Austin, Texas. Bob, Elaine, and Nicole have offered support and counsel throughout this journey. Neto has been battling skin cancer since being diagnosed during our first ABA reunion in 1997. Neto says, “I spent a lot of time in the sun when I was younger. Annual checkups are now a part of my routine.” Longtime readers of my column might recall that rocker Warren Zevon has been a constant in our relationship since the beginning. On his last appearance on David Letterman’s Late Show, Zevon, who passed away from cancer in 2003, advised his fans to “Enjoy every sandwich.”

So, I asked Rhonda if she had any advice of her own. “I worry about people like me who had no idea how serious this thing is. Joggers, walkers, golfers, bicyclists, people who work or spend time outdoors professionally or recreationally. Skin cancer can sneak up on you, and it is serious. Don’t take it for granted. If you’re outside, wear a hat and make sunscreen a part of your daily routine. My Buc-ee’s straw hat is now a part of my regular gear. And it looks pretty cool.”