Original publish date: December 14, 2013

Original publish date: December 14, 2013

This past November, I shared with you a series of articles commemorating the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg address. The speech is well known to most Americans and the words Mr. Lincoln spoke that day were once required memorization for every student in this country. The minutia surrounding the speech would make a Hollywood script writer salivate; Lincoln’s son Tad was left behind at the White House with a raging fever, Lincoln was asked to attend the cemetery dedication as an afterthought, the ground upon which he spoke was literally still wet with the blood of dead American soldiers and now Lincoln himself was showing signs of the fevered weakness of smallpox.

By all accounts, it was Lincoln’s African American valet William H. Johnson who identified the symptoms, alleviated the problem and nursed the President back to health. What? A black man saved Abraham Lincoln’s life after Gettysburg? Why have we never heard of William H. Johnson? Almost all that is known of him comes from Lincoln’s Papers. Although recently, Hollywood tried to put it’s own spin on the good Mr. Johnson. In the entirely forgettable 2012 film “Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter”, they replaced the young railsplitter’s literary “sidekick” with his White House Valet, William Johnson, played by actor Anthony Mackie. Did I mention that was Hollywood though? Now, let me tell you the real story and let’s try to set the record straight.

William Henry Johnson was born around 1835 in a site unknown. He was described as a free “colored man” who came with the Lincoln family from Springfield Illinois to become the newly elected President’s valet and barber. He has no surviving photograph, and we can only speculate as to his age. He was, however, very close to the president. He had been serving Mr. Lincoln for about a year when his employer wrote him a note of recommendation on March 7, 1861. Seems that even a President had to get confirmation for a desired new hire back in those days. It stated: “Whom it may concern. William Johnson, a colored boy, and bearer of this, has been with me about twelve months; and has been, so far, as I believe, honest, faithful, sober, industrious, and handy as a servant. A. LINCOLN.” Although he served as the President’s valet, the President’s House Register listed him in 1861 as “W. H. Johnson, Fireman, President’s House, $600 per annum.”

It appears that there was antagonism toward Johnson from the start. Some believe it was due to Mr. Johnson’s close relationship with the President. Most of the opposition came from the existing White House staff, who were generally lighter skinned, “high yellow”, that is to say, almost white. So, a White House job was apparently out of the question. President Lincoln sought other employment for Johnson only days after his inauguration. In a letter to Navy Secretary Gideon Welles on March 7, 1861, the President asked the secretary to give employment to W. Johnson, “a servant who has been with me for some time.” In that same letter, Lincoln notes that “The difference of color between him & other servants is the cause of our separation.” explained Lincoln. “I have confidence as to his integrity and faithfulness.” Even though Welles was as close a friend as Lincoln had in all of Washington, his plea evidently fell on deaf ears.

In a subsequent letter to Salmon Chase, he successfully sought a position for Johnson in the Treasury Department. On November 29,1861, Lincoln wrote Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase: “You remember kindly asking me, some time ago whether I really desired you to find a place for William Johnson, a colored boy who came from Illinois with me. If you can find him the place shall really be obliged. Yours truly A. LINCOLN.” He was then given a place as laborer / messenger with the Treasury Department at $600 per year. From then on, he worked for the Treasury in the afternoon and tended to Lincoln’s wardrobe, shaved him, and did other personal services for Mr. Lincoln in the morning and evening.

On March 11, 1862, the President wrote Johnson a personal check for $5. October 24, 1862, again found Lincoln writing a recommendation for him reading: “The bearer of this, William Johnson (colored), came with me from Illinois; and is a worthy man, as I believe. A. LINCOLN.” Nevertheless, on December 17, 1862 the President declined to endorse a memo for Johnson because he did not want it to be mistaken as an order for employment. The memorandum, referring to a request for leave of absence for his valet in order to earn extra money, reads: “I decline to sign the within, because it does not state the thing quite to my liking. The colored man William Johnson came with me from Illinois, and I would be glad for him to be obliged, if he can be consistently with the public service; but I can not make an order about it, nor a request which might, in some sort, be construed as an order. A. LINCOLN.”

On November 18, 1863, Lincoln wrote a note explaining that Johnson would travel with him to Gettysburg for the dedication of the soldiers’ cemetery. The note, written to the Treasury Department, asks to borrow Johnson’s services for a “whole day or two” and closes simply: “William goes with me.” Mrs. Lincoln remained at the White House attending to their son Tad. Once in Gettysburg. After delivering his address, Lincoln began to feel ill and while aboard the return train to Washington “lay in a relaxed position with a wet towel across his head,” placed there by Johnson. The details of the President’s recovery were covered in detail in part III of the November Lincoln at Gettysburg series. Although the President would recover, Mr. Lincoln may have unwittingly passed the illness on to his valet.

On November 18, 1863, Lincoln wrote a note explaining that Johnson would travel with him to Gettysburg for the dedication of the soldiers’ cemetery. The note, written to the Treasury Department, asks to borrow Johnson’s services for a “whole day or two” and closes simply: “William goes with me.” Mrs. Lincoln remained at the White House attending to their son Tad. Once in Gettysburg. After delivering his address, Lincoln began to feel ill and while aboard the return train to Washington “lay in a relaxed position with a wet towel across his head,” placed there by Johnson. The details of the President’s recovery were covered in detail in part III of the November Lincoln at Gettysburg series. Although the President would recover, Mr. Lincoln may have unwittingly passed the illness on to his valet.

The story of Johnson’s death is not much clearer than that of his life, since the chaos of war left death and burial records in disarray. What we know is that by by January 12, 1864 Johnson was himself sick with smallpox. By the 28th, he was dead. In a January 12th interview with the Chicago Tribune, Lincoln told the reporter than he didn’t believe that he gave smallpox to Johnson. But based on the late November speech date, given the incubation period of about two weeks and the average time for the illness to run its fatal course, that’s about the right timing for a disease contracted while caring for Lincoln. However, if it was circulating around residents and staff at the White House, it is possible that Johnson contracted it from someone else.

During that Chicago Tribune interview, the journalist found Abraham Lincoln busy counting greenbacks. The money belonged to Johnson who was in the hospital, so sick that he could not even draw his pay. “This, sir, is something out of my usual line,” the president told the reporter, “but a president of the United States has a multiplicity of duties not specified in the Constitution or acts of Congress. This is one of them. This money belongs to a poor negro [Johnson] who is a porter in one of the departments (the Treasury) and who is at present very bad with the smallpox. He did not catch it from me, however; at least I think not. He is now in hospital, and could not draw his pay because he could not sign his name. I have been at considerable trouble to overcome the difficulty and get it for him, and have at length succeeded in cutting red tape, as you newspaper men say. I am now dividing the money and putting by a portion labeled, in an envelope, with my own hands, according to his wish.”

During that Chicago Tribune interview, the journalist found Abraham Lincoln busy counting greenbacks. The money belonged to Johnson who was in the hospital, so sick that he could not even draw his pay. “This, sir, is something out of my usual line,” the president told the reporter, “but a president of the United States has a multiplicity of duties not specified in the Constitution or acts of Congress. This is one of them. This money belongs to a poor negro [Johnson] who is a porter in one of the departments (the Treasury) and who is at present very bad with the smallpox. He did not catch it from me, however; at least I think not. He is now in hospital, and could not draw his pay because he could not sign his name. I have been at considerable trouble to overcome the difficulty and get it for him, and have at length succeeded in cutting red tape, as you newspaper men say. I am now dividing the money and putting by a portion labeled, in an envelope, with my own hands, according to his wish.”

After Johnson’s passing, Lincoln learned that his friend had borrowed $150 from the First National Bank of Washington using Lincoln as a reference. The bank’s cashier, William J. Huntington, happened to mention the outstanding notes to Lincoln: “the barber who used to shave you, I hear, is dead.”

“‘Oh, yes,’ interrupted the President, with feeling; ‘William is gone. I bought a coffin for the poor fellow, and have had to help his family.’” When Huntington said the bank would forgive the loan, Lincoln replied emphatically: “No you don’t. I endorsed the notes, and am bound to pay them; and it is your duty to make me pay them.”

“Yes,” said the banker, “but it has long been our custom to devote a portion of our profits to charitable objects; and this seems to be a most deserving one.” When the president rejected that argument, Huntington said: “Well, Mr. Lincoln, I will tell you how we can arrange this. The loan to William was a joint one between you and the bank. You stand half of the loss, and I will cancel the other.” After thinking it over, Lincoln said: “Mr. Huntington, that sounds fair, but it is insidious; you are going to get ahead of me; you are going to give me the smallest note to pay. There must be a fair divide over poor William. Reckon up the interest on both notes, and chop the whole right straight through the middle, so that my half shall be as big as yours. That’s the way we will fix it.” Huntington agreed, saying: “After this, Mr. President, you can never deny that you endorse the negro.” “That’s a fact!” Lincoln exclaimed with a laugh; “but I don’t intend to deny it.”

Although the exact day of Johnson’s death is not known we do know that on January 28, 1864, Lincoln wrote a recommendation for Solomon James Johnson (it’s unknown if he was related) to Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase: “This boy says he knows Secretary Chase, and would like to have the place made vacant by William Johnson’s death. I believe he is a good boy and I should be glad for him to have the place if it is still vacant. A. LINCOLN.”

While he shared a racial view typical of many white northern moderates, Lincoln clearly thought highly of Johnson. The incident reveals Lincoln’s humanity at its best. The working relationship between the two men attests to the complex and even enigmatic nature of Lincoln’s racial attitudes in general. Indeed, the mystery that surrounds Johnson’s death, and Lincoln’s sense of responsibility for it, tells us much about the “Great Emancipator’s” complex relationship with African Americans and their quest for full citizenship.

Lincoln requested that his valet be buried on the Arlington Mansion grounds (the Custis-Lee estate’s official conversion to Arlington National cemetery was still several months away) and used his own personal funds to pay all funeral service expenses including the tombstone. That original stone no longer exists. He now rests under a circa-1990s Era government issued stone with the name and a single word added by his friend, the President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. While no-one will ever truly know the depth of the personal relationship between the two men, the depth of respect can not be denied. The headstone, found in Plot 3346- Section 27 of Arlington National Cemetery, reads simply: “WILLIAM H JOHNSON. CITIZEN.”

Original publish date: March 20, 2014

Original publish date: March 20, 2014 On Saturday, March 15th the museum’s contents were sold to the public at auction. The sale included 95 Civil War wax figures and the accouterments used to illustrate each scene. In it’s half century of service the museum saw over 8 million visitors walk through the turnstiles, now lot # 265 in this very special auction.

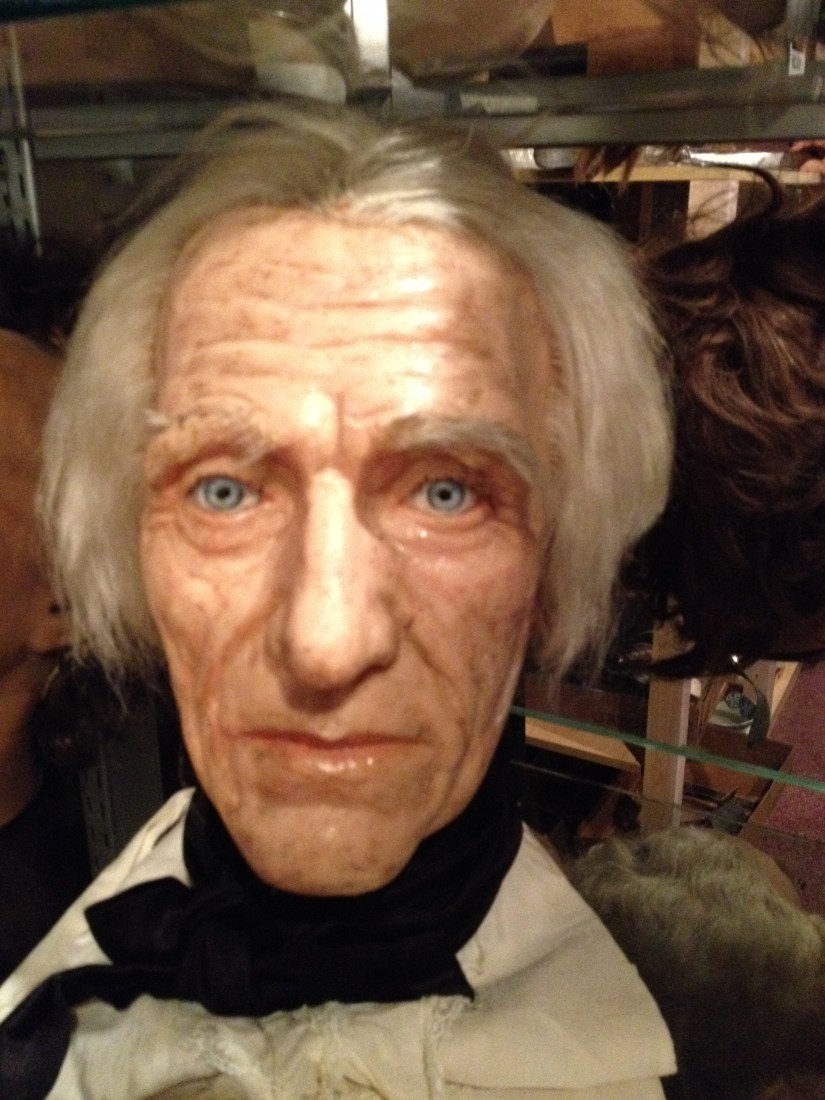

On Saturday, March 15th the museum’s contents were sold to the public at auction. The sale included 95 Civil War wax figures and the accouterments used to illustrate each scene. In it’s half century of service the museum saw over 8 million visitors walk through the turnstiles, now lot # 265 in this very special auction. As I finished perusing the auction lots, I halted at an area tucked away in a back corner of the hall. This dimly lit crook featured tiered shelves upon which rested approximately 40 disembodied heads. Some of the heads were recognizable to me; Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Jackson. On a shelf nearby lay a pile of arms, legs and hands. Some of these body parts, in keeping with the brutality of the Civil War, were spattered with blood stains. Seeing these, I turned to my wife and said “Now these have the potential to go sky high.”

As I finished perusing the auction lots, I halted at an area tucked away in a back corner of the hall. This dimly lit crook featured tiered shelves upon which rested approximately 40 disembodied heads. Some of the heads were recognizable to me; Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Jackson. On a shelf nearby lay a pile of arms, legs and hands. Some of these body parts, in keeping with the brutality of the Civil War, were spattered with blood stains. Seeing these, I turned to my wife and said “Now these have the potential to go sky high.” The synchronicity of the moment was not lost on me as, outside just yards away, bulldozers busily cleared out the massive football field sized blacktop parking lot. It had once served the old visitor’s center (torn down in 2008) and Cyclorama building, built the same year as the wax museum and torn down in March 2013. In the past 25 years I watched as other tourist landmarks disappeared from the borough including the Lincoln Room Museum, The National Tower, and now, the Wax Museum.

The synchronicity of the moment was not lost on me as, outside just yards away, bulldozers busily cleared out the massive football field sized blacktop parking lot. It had once served the old visitor’s center (torn down in 2008) and Cyclorama building, built the same year as the wax museum and torn down in March 2013. In the past 25 years I watched as other tourist landmarks disappeared from the borough including the Lincoln Room Museum, The National Tower, and now, the Wax Museum. Undoubtedly the happiest person in the room that day was a young woman named Kim Yates. She was hard to miss. Towards the end of the auction she bid on, and won, the last wax figure in the catalog. Suddenly, the previously sedate young lady began to scream wildly and jump around the room. One of the ringmen sidled over to me, after noting the look of obvious surprise on my face, and whispered, “She’s never bid in an auction before.”

Undoubtedly the happiest person in the room that day was a young woman named Kim Yates. She was hard to miss. Towards the end of the auction she bid on, and won, the last wax figure in the catalog. Suddenly, the previously sedate young lady began to scream wildly and jump around the room. One of the ringmen sidled over to me, after noting the look of obvious surprise on my face, and whispered, “She’s never bid in an auction before.”