Original publish date: May 14, 2020

Like all Americans, Covid-19 is affecting my life and adjusting my normal routine. For more than a quarter century, the Hunter family has ventured down to Daytona Beach, Florida every spring for an annual getaway. Well, that vacay was cancelled this year. The seriousness of this pandemic far outweigh a lost vacation and, when viewed alongside the sufferings of many of my fellow Hoosiers, is a minor issue indeed. So, since we are all confined to quarters together, I decided to write about a few things I have always loved about Daytona Beach.

There is a lot of history on the world’s most famous beach: cars, gangsters, auto racing, motorcycles, bootleggers and Henry Ford, for starters. When you think of auto racing, two American cities come to mind: Indianapolis and Daytona. However, before Indianapolis and Daytona, Ormond Beach was the mecca of auto racing. Ormond Beach just north of Daytona, held races on the beach from 1902 until after World War II. At that time, Ormond Beach was a playground for America’s rich and famous: The Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, Roosevelts, Henry Flagler, John Jacob Astor; all spent their winters at the old Ormond Hotel.

There is a lot of history on the world’s most famous beach: cars, gangsters, auto racing, motorcycles, bootleggers and Henry Ford, for starters. When you think of auto racing, two American cities come to mind: Indianapolis and Daytona. However, before Indianapolis and Daytona, Ormond Beach was the mecca of auto racing. Ormond Beach just north of Daytona, held races on the beach from 1902 until after World War II. At that time, Ormond Beach was a playground for America’s rich and famous: The Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, Roosevelts, Henry Flagler, John Jacob Astor; all spent their winters at the old Ormond Hotel.

From 1902 to 1935, auto industry giants such as Henry Ford, Louis Chevrolet, and Ransom E. Olds brought their cars to race on the beach. Cigar-chomping Barney Oldfield, the most famous race-car driver in the world at the time, set a new world speed record on the Ormond-Daytona course in 1907. Racing faded somewhat in Ormond and Daytona after World War I as the racing world turned its attention to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

From 1902 to 1935, auto industry giants such as Henry Ford, Louis Chevrolet, and Ransom E. Olds brought their cars to race on the beach. Cigar-chomping Barney Oldfield, the most famous race-car driver in the world at the time, set a new world speed record on the Ormond-Daytona course in 1907. Racing faded somewhat in Ormond and Daytona after World War I as the racing world turned its attention to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

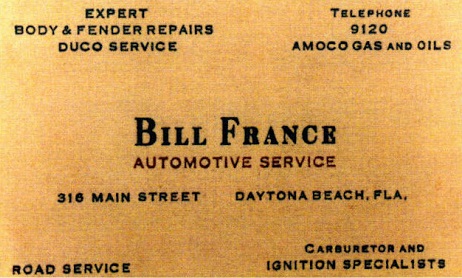

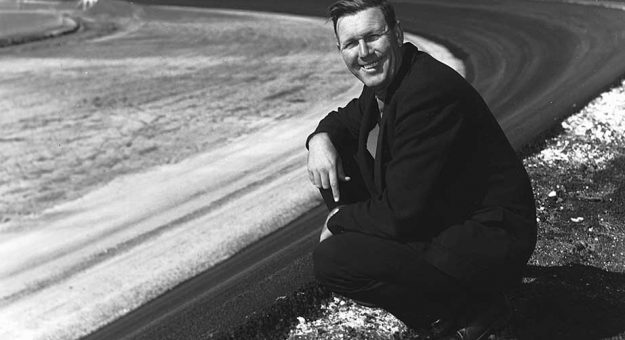

In 1936 the American Automobile Association sponsored the first national stock-car race on Daytona Beach. One of the drivers was Bill France, who later founded NASCAR. The first stock-car race after World War II was held in the spring of 1946. During that race, Bill France flipped has race his car and spectators rushed onto the beach to turn the car back on its wheels. Bill France finished the race. The next year, France began planning the construction of Daytona International Speedway 5 miles east of the beach.

In 1937 Bill France, now a promoter and no longer a driver, arranged for the Savannah 200 Motorcycle race to be moved to the 3.2-mile Daytona Beach Road Course. World War II cancelled the races held between 1942 and 1946. By 1948, the old beach course had become so developed commercially that a new beach course was designed further south, towards Ponce Inlet (where our family time-share condo is located). The new course length was increased from the previous 3.2 miles to 4.1-miles. By the mid-1950s, the new beach course was lost to the rapid commercial growth of the Daytona Beach area.

In 1957, France purchased a site near the Daytona airport and construction began on the Daytona International Speedway, a 2.5-mile paved, oval-shaped circuit with steep banked curves to facilitate higher speeds. The track opened in 1958. The first Daytona 500, run in 1959, was won by Lee Petty, father of Richard Petty. France convinced AMA officials to move the beach race to the Speedway in 1961. Today, the motorcycle racers are honored in a memorial garden, not unlike monument park in Yankee Stadium, located near the bandshell and Ferris Wheel off the Daytona Beach Boardwalk. Bill France is as much a legend in Daytona as Tony Hulman is in the Circle City and Henry Ford in the Motor City.

Although Henry Ford raced cars as a young man (he was the first American to claim a land speed record with his “flying mile” in 39.4 seconds, averaging 91.370 miles per hour in his “999” car on January 12, 1904) and attended many of the early Indianapolis 500 races as an honorary official, he did not allow his cars to take part in the races. In 1935 Edsel Ford brought his Ford V8 Miller to the IMS and after the elder Ford’s death in April 1947, the company had considerable success at Indianapolis (Mario Andretti won in a Ford powered turbocharged dohc “Indy” V-8 known as the “Hawk” in 1969). Bottom line, in the early years of automobiles, Henry Ford’s cars were fast.

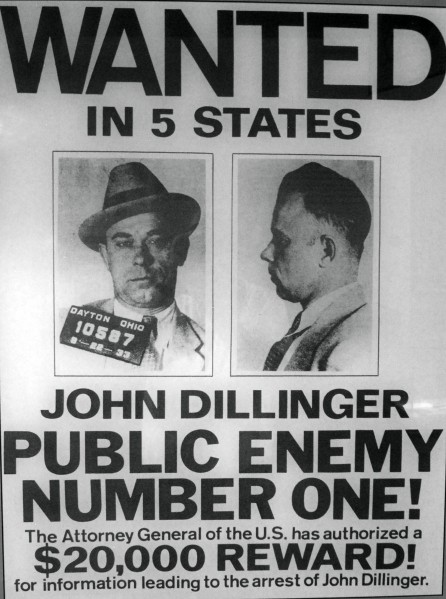

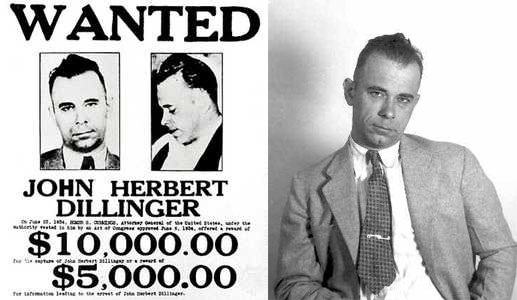

So it comes as no surprise that the gangsters of the 1930s drove Fords. In particular, outlaws John Dillinger, Bonnie and Clyde and Baby Face Nelson all preferred the Ford Model V8. Introduced in 1932, it was touted as America’s first affordable big-engine car. Dillinger also is said to have owned a Model A and what’s more, in mid-December of 1933, he drove his Ford to Daytona Beach for a vacation. After secretly visiting the Dillinger family farm in Mooresville, America’s first Public Enemy # 1 brought along girlfriend Evelyn “Billie” Frechette, Hoosier “Handsome Harry” Pierpont and his “molls” Mary Kinder, her sister Margaret and Opal Long and gang members Russell Clark and Fat Charlie Makley. The gang rented a spacious 3-story, seventeen room beach house for $ 100 a month at 901 South Atlantic Avenue until Mid-January, 1934. The house, long ago demolished, was located across the street from Seabreeze high school on the spot where “Riptides Raw Bar & Grill” and the Aliki Atrium are located today. Vacationers will recognize the “Riptides” name from the banner pulled by the tail of an airplane that constantly trails up and down Daytona beach.

So it comes as no surprise that the gangsters of the 1930s drove Fords. In particular, outlaws John Dillinger, Bonnie and Clyde and Baby Face Nelson all preferred the Ford Model V8. Introduced in 1932, it was touted as America’s first affordable big-engine car. Dillinger also is said to have owned a Model A and what’s more, in mid-December of 1933, he drove his Ford to Daytona Beach for a vacation. After secretly visiting the Dillinger family farm in Mooresville, America’s first Public Enemy # 1 brought along girlfriend Evelyn “Billie” Frechette, Hoosier “Handsome Harry” Pierpont and his “molls” Mary Kinder, her sister Margaret and Opal Long and gang members Russell Clark and Fat Charlie Makley. The gang rented a spacious 3-story, seventeen room beach house for $ 100 a month at 901 South Atlantic Avenue until Mid-January, 1934. The house, long ago demolished, was located across the street from Seabreeze high school on the spot where “Riptides Raw Bar & Grill” and the Aliki Atrium are located today. Vacationers will recognize the “Riptides” name from the banner pulled by the tail of an airplane that constantly trails up and down Daytona beach.

Billie later called the house a mansion with four fireplaces. The gang swam, played cards, fished, went horseback riding and reportedly took a side-trip to Miami. Billie also stated that Dillinger spent his days chuckling as he listened to radio reports and read newspaper stories about the robberies he and the gang were committing back in Illinois and Indiana. On New Years Eve a drunken Dillinger (who normally drank very little) exited the house and fired a full drum of bullets from his tommy gun at the moon. Three young boys, the Warnock brothers, lived next door and ran out to see what was going on. When they saw Dillinger with flames spitting out of the muzzle of his tommy gun, they quickly ran back into the house. Sobering up the next morning and sure that his rash act would bring on the law, Dillinger and the gang packed up the Ford V8 and head out two weeks before the rental contract ended.

By January 1, 1934, John Dillinger had just two hundred days to live. He would spend that time praising Henry Ford and damning Bonnie and Clyde, who, ironically had less than 150 days to live and were also praising Henry Ford.

Next week:

Part II of Daytona Beach, Henry Ford, John Dillinger and Bonnie & Clyde.

Located at 815 Massachusetts Avenue near the headquarters of the Indiana State Police, Dillinger and Vinson brazenly strolled into the bank with guns drawn. Assistant manager Lloyd Rinehart, seated at his desk chatting casually on the telephone, heard someone yell: “This is a stickup! We mean business.” He later told police that he thought it was a joke and didn’t even look up to interrupt his conversation. “Get off that damned telephone,” Dillinger snarled. Rinehart looked up from his desk to find he was staring into the barrel of a .45 automatic.

Located at 815 Massachusetts Avenue near the headquarters of the Indiana State Police, Dillinger and Vinson brazenly strolled into the bank with guns drawn. Assistant manager Lloyd Rinehart, seated at his desk chatting casually on the telephone, heard someone yell: “This is a stickup! We mean business.” He later told police that he thought it was a joke and didn’t even look up to interrupt his conversation. “Get off that damned telephone,” Dillinger snarled. Rinehart looked up from his desk to find he was staring into the barrel of a .45 automatic.

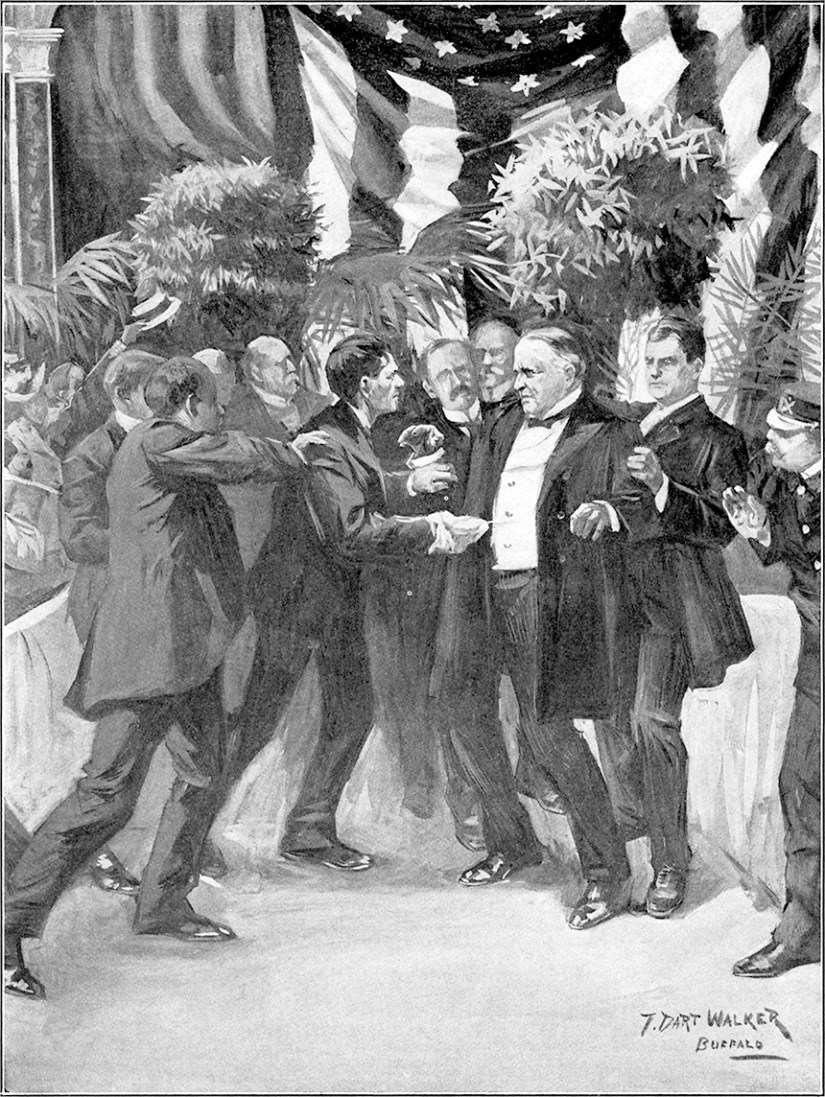

The president was scheduled to meet the thousands of people who, in spite of the oppressive heat, were waiting at the Temple of Music on the north side of the fairgrounds. In that line, no one stood out more than James “Big Ben” Parker, a six-foot six inch, 250 pound “Negro” waiter from Atlanta who has been laid off by the exposition’s Plaza Restaurant only days before. One could conclude that “Big Ben” was the angriest man in the room and the one the Secret Service should be watching. However, that sobriquet would belong to the man standing immediately in front of the gentle giant. A stoop-shouldered, nervous little man whose hand was wrapped in a handkerchief.

The president was scheduled to meet the thousands of people who, in spite of the oppressive heat, were waiting at the Temple of Music on the north side of the fairgrounds. In that line, no one stood out more than James “Big Ben” Parker, a six-foot six inch, 250 pound “Negro” waiter from Atlanta who has been laid off by the exposition’s Plaza Restaurant only days before. One could conclude that “Big Ben” was the angriest man in the room and the one the Secret Service should be watching. However, that sobriquet would belong to the man standing immediately in front of the gentle giant. A stoop-shouldered, nervous little man whose hand was wrapped in a handkerchief. The first bullet sheared a button off of McKinley’s vest, the second tore into the President’s abdomen. The handkerchief burst into flames and fell to the floor. McKinley lurched forward as Czolgosz took aim for a third shot. Within seconds after the second pistol shot, Big Ben Parker was grappling with the adrenaline charged assassin. Secret service special agent Samuel Ireland described the scene: “Parker struck the assassin in the neck with one hand and with the other reached for the revolver which had been discharged through the handkerchief and the shots had set fire to the linen. While on the floor Czolgosz again tried to discharge the revolver but before he got to the president the Negro knocked it from his hand.” A split second after Parker struck Czolgosz, so did Buffalo detective John Geary and one of the artillerymen, Francis O’Brien. Czolgosz disappeared beneath a pile of men, some of whom were punching or hitting him with rifle butts. The assassin cried out, “I done my duty.”

The first bullet sheared a button off of McKinley’s vest, the second tore into the President’s abdomen. The handkerchief burst into flames and fell to the floor. McKinley lurched forward as Czolgosz took aim for a third shot. Within seconds after the second pistol shot, Big Ben Parker was grappling with the adrenaline charged assassin. Secret service special agent Samuel Ireland described the scene: “Parker struck the assassin in the neck with one hand and with the other reached for the revolver which had been discharged through the handkerchief and the shots had set fire to the linen. While on the floor Czolgosz again tried to discharge the revolver but before he got to the president the Negro knocked it from his hand.” A split second after Parker struck Czolgosz, so did Buffalo detective John Geary and one of the artillerymen, Francis O’Brien. Czolgosz disappeared beneath a pile of men, some of whom were punching or hitting him with rifle butts. The assassin cried out, “I done my duty.” A Los Angeles Times story said that “with one quick shift of his clenched fist, he [Parker] knocked the pistol from the assassin’s hand. With another, he spun the man around like a top and with a third, he broke Czolgosz’s nose. A fourth split the assassin’s lip and knocked out several teeth.” In Parker’s own account, given to a newspaper reporter a few days later, he said, “I heard the shots. I did what every citizen of this country should have done. I am told that I broke his nose—I wish it had been his neck. I am sorry I did not see him four seconds before. I don’t say that I would have thrown myself before the bullets. But I do say that the life of the head of this country is worth more than that of an ordinary citizen and I should have caught the bullets in my body rather than the President should get them.” In a separate interview for the New York Journal, Parker remarked “just think, Father Abe freed me, and now I saved his successor from death, provided that bullet he got into the president don’t kill him.”

A Los Angeles Times story said that “with one quick shift of his clenched fist, he [Parker] knocked the pistol from the assassin’s hand. With another, he spun the man around like a top and with a third, he broke Czolgosz’s nose. A fourth split the assassin’s lip and knocked out several teeth.” In Parker’s own account, given to a newspaper reporter a few days later, he said, “I heard the shots. I did what every citizen of this country should have done. I am told that I broke his nose—I wish it had been his neck. I am sorry I did not see him four seconds before. I don’t say that I would have thrown myself before the bullets. But I do say that the life of the head of this country is worth more than that of an ordinary citizen and I should have caught the bullets in my body rather than the President should get them.” In a separate interview for the New York Journal, Parker remarked “just think, Father Abe freed me, and now I saved his successor from death, provided that bullet he got into the president don’t kill him.”

Historians agree that Czolgosz’s trial was a sham. Sadly, what should have been Big Ben Parker’s time to shine instead became his disappearing act. Prior to the trial, which began September 23, 1901, Parker was expected to be a major character in the assassination saga. Instead,the trial minimized Parker’s participation in the events of three weeks prior. Parker was never asked to testify and those few participants who did never identified Big Ben as the person who first subdued the assassin. Czolgosz’s sanity was never questioned and the case was closed twenty-four hours after it opened. Newspaper reports after the trial failed to mention Big Ben’s role and witnesses, including lawyers and Secret Service agents, began to enlarge their own roles in the tragedy by going as far as saying they “saw no Negro involved” whatsoever.

Historians agree that Czolgosz’s trial was a sham. Sadly, what should have been Big Ben Parker’s time to shine instead became his disappearing act. Prior to the trial, which began September 23, 1901, Parker was expected to be a major character in the assassination saga. Instead,the trial minimized Parker’s participation in the events of three weeks prior. Parker was never asked to testify and those few participants who did never identified Big Ben as the person who first subdued the assassin. Czolgosz’s sanity was never questioned and the case was closed twenty-four hours after it opened. Newspaper reports after the trial failed to mention Big Ben’s role and witnesses, including lawyers and Secret Service agents, began to enlarge their own roles in the tragedy by going as far as saying they “saw no Negro involved” whatsoever.

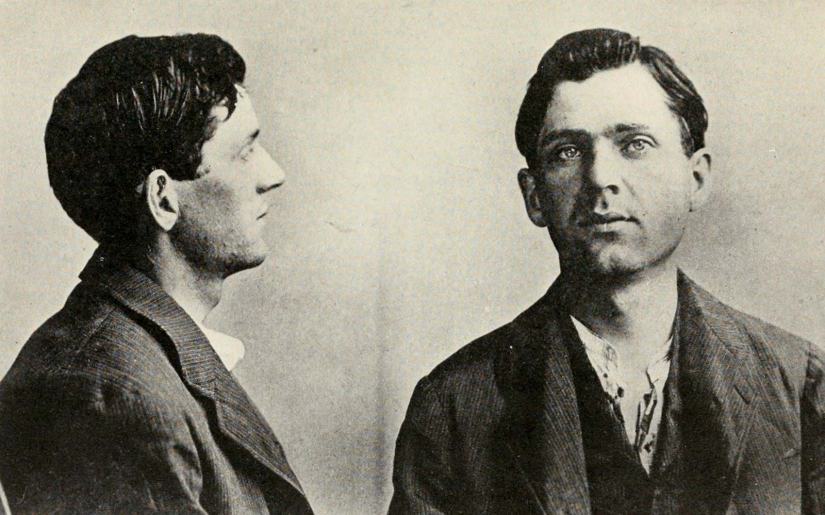

Just as Big Ben is the forgotten figure in the McKinley assassination saga, Leon Czolgosz is the least known of all presidential assassins. Prior to his execution Czolgosz met with two priests and said, “No. Damn them. Don’t send them here again. I don’t want them. And don’t you have any praying over me when I’m dead. I don’t want it. I don’t want any of their damned religion.” Czolgosz was electrocuted on October 29, 1901 at Auburn penitentiary. Initially, Czolgosz’s family wanted the body. The warden convinced them that it would be a bad idea, that relic hunters would disturb his grave, or worse, that unscrupulous carnival promoters would want to display the body in traveling sideshows.

Just as Big Ben is the forgotten figure in the McKinley assassination saga, Leon Czolgosz is the least known of all presidential assassins. Prior to his execution Czolgosz met with two priests and said, “No. Damn them. Don’t send them here again. I don’t want them. And don’t you have any praying over me when I’m dead. I don’t want it. I don’t want any of their damned religion.” Czolgosz was electrocuted on October 29, 1901 at Auburn penitentiary. Initially, Czolgosz’s family wanted the body. The warden convinced them that it would be a bad idea, that relic hunters would disturb his grave, or worse, that unscrupulous carnival promoters would want to display the body in traveling sideshows. His family agreed that the prison should take care of the funeral arrangements by giving the assassin a decent burial within the protection of the prison grounds. When Leon Czolgosz was buried in the Auburn prison cemetery, yards away from where he was executed, unbeknownst to the family, the decision was made to have his body destroyed. The local crematorium refused to undertake the job. So the assassin’s body was placed in a rough pine box and lowered into the ground which had been coated with quicklime. The lid was removed and two barrels of quicklime powder was caked on top of the body. Then sulfuric acid was poured on top of that followed by another two layers of quicklime.

His family agreed that the prison should take care of the funeral arrangements by giving the assassin a decent burial within the protection of the prison grounds. When Leon Czolgosz was buried in the Auburn prison cemetery, yards away from where he was executed, unbeknownst to the family, the decision was made to have his body destroyed. The local crematorium refused to undertake the job. So the assassin’s body was placed in a rough pine box and lowered into the ground which had been coated with quicklime. The lid was removed and two barrels of quicklime powder was caked on top of the body. Then sulfuric acid was poured on top of that followed by another two layers of quicklime. Their intention was to make the anarchist’s body dematerialize. What the prison officials did not know was that when quicklime (calcium oxide) and sulfuric acid are combined, a chemical reaction occurs which creates an exterior coating best compared to plaster of paris. Since the shell is insoluble in water, the coating acts as a protective layer thus preventing further attack on the corpse by the acid. It is entirely possible that the body of Czolgosz was preserved in perpetuity accidentally.

Their intention was to make the anarchist’s body dematerialize. What the prison officials did not know was that when quicklime (calcium oxide) and sulfuric acid are combined, a chemical reaction occurs which creates an exterior coating best compared to plaster of paris. Since the shell is insoluble in water, the coating acts as a protective layer thus preventing further attack on the corpse by the acid. It is entirely possible that the body of Czolgosz was preserved in perpetuity accidentally.

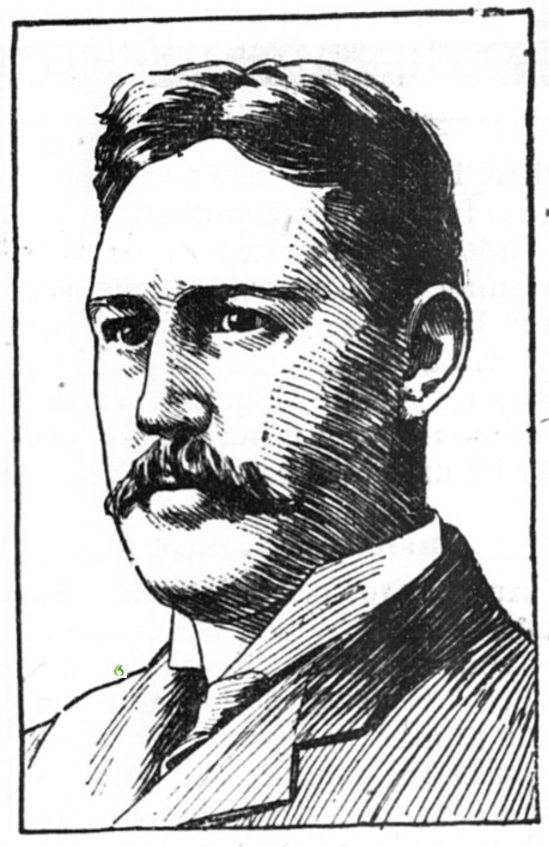

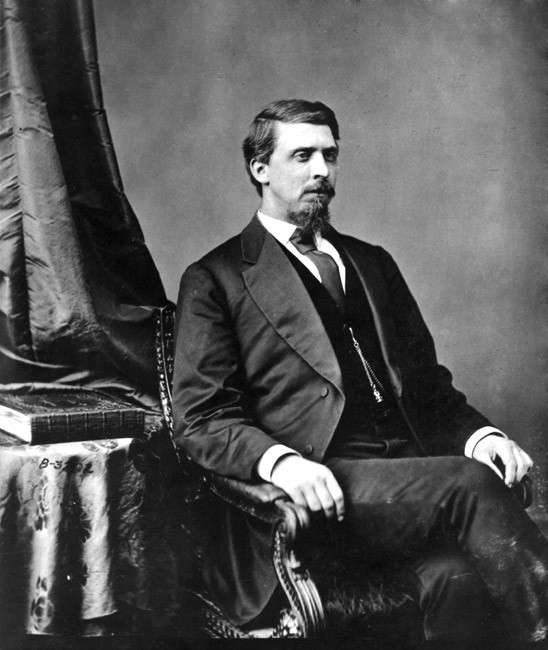

Most Americans remember President William McKinley solely for the way he died. His image a milquetoast chief executive from the age of American Imperialism who was at the helm for the dawn of the 20th century. McKinley’s ordinary appearance belied the fact that he was the last president to have served in the American Civil War and the only one to have started the war as an enlisted soldier. It is long forgotten that McKinley led the nation to victory in the Spanish-American War, protected American industry by raising tariffs, and kept the nation on the gold standard by rejecting free silver. Most notably, his assassination at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York unleashed the central figure who would come to personify the new century; his Vice-President Teddy Roosevelt.

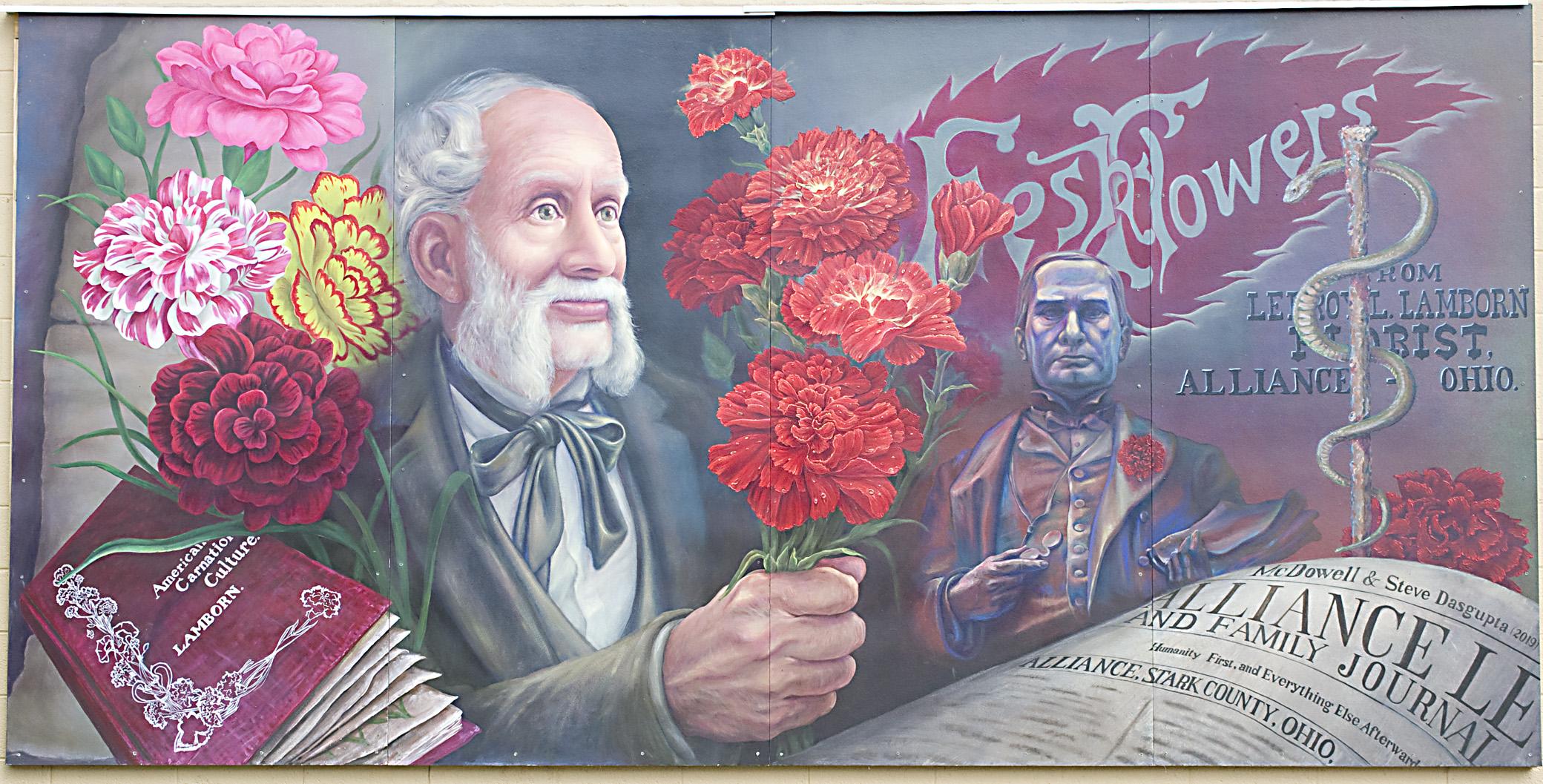

Most Americans remember President William McKinley solely for the way he died. His image a milquetoast chief executive from the age of American Imperialism who was at the helm for the dawn of the 20th century. McKinley’s ordinary appearance belied the fact that he was the last president to have served in the American Civil War and the only one to have started the war as an enlisted soldier. It is long forgotten that McKinley led the nation to victory in the Spanish-American War, protected American industry by raising tariffs, and kept the nation on the gold standard by rejecting free silver. Most notably, his assassination at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York unleashed the central figure who would come to personify the new century; his Vice-President Teddy Roosevelt. McKinley’s favorite flower was a red carnation. He displayed his affection by wearing one of the bright red florets in his lapel every day. The carnation boutonnière soon became McKinley’s personal trademark. As President, bud vases filled with red carnations were conspicuously placed around the White House (known as the “Executive Mansion” back then). Whenever a guest visited the President, McKinley’s custom was to remove the carnation from his lapel and present it to the star-struck visitor. For men, he would often place the souvenir blossom into the lapel himself and suggest that it be given to an absent wife, mother, or child. Afterward, he would replace his boutonnière with another from a nearby vase and repeat the transfer again and again for the rest of the day. McKinley was superstitious about these carnations, believing that they brought good luck to both him and his recipient.

McKinley’s favorite flower was a red carnation. He displayed his affection by wearing one of the bright red florets in his lapel every day. The carnation boutonnière soon became McKinley’s personal trademark. As President, bud vases filled with red carnations were conspicuously placed around the White House (known as the “Executive Mansion” back then). Whenever a guest visited the President, McKinley’s custom was to remove the carnation from his lapel and present it to the star-struck visitor. For men, he would often place the souvenir blossom into the lapel himself and suggest that it be given to an absent wife, mother, or child. Afterward, he would replace his boutonnière with another from a nearby vase and repeat the transfer again and again for the rest of the day. McKinley was superstitious about these carnations, believing that they brought good luck to both him and his recipient. One account alleges that McKinley’s “Genus Dianthus” custom began early in his presidency when an aide brought his two sons to the White House to meet the President. McKinley, who loved children dearly, presented his carnation to the older boy. Seeing the disappointment in the younger boy’s face, the President deftly retrieved a replacement carnation and pinned it on his own lapel. Here the flower remained for a few moments before he removed it and gave to the younger child, explaining “this way you both can have a carnation worn by the President.”

One account alleges that McKinley’s “Genus Dianthus” custom began early in his presidency when an aide brought his two sons to the White House to meet the President. McKinley, who loved children dearly, presented his carnation to the older boy. Seeing the disappointment in the younger boy’s face, the President deftly retrieved a replacement carnation and pinned it on his own lapel. Here the flower remained for a few moments before he removed it and gave to the younger child, explaining “this way you both can have a carnation worn by the President.” However, McKinley’s ubiquitous floral tradition can be traced to the election of 1876, when he was running for a seat in Congress. His opponent, Dr. Levi Lamborn, of Alliance, Ohio, was an accomplished amateur horticulturist famed for developing a strain of vivid scarlet carnations he dubbed “Lamborn Red.” Dr. Lamborn presented McKinley with a “Lamborn Red” boutonniere before their debates. After he won the election, McKinley viewed the red carnation as a good luck charm. He wore one on his lapel regularly and soon began his custom of presenting them to visitors. He wore one during his fourteen years in Congress, his two gubernatorial wins and both 1896 and 1900 presidential campaigns.

However, McKinley’s ubiquitous floral tradition can be traced to the election of 1876, when he was running for a seat in Congress. His opponent, Dr. Levi Lamborn, of Alliance, Ohio, was an accomplished amateur horticulturist famed for developing a strain of vivid scarlet carnations he dubbed “Lamborn Red.” Dr. Lamborn presented McKinley with a “Lamborn Red” boutonniere before their debates. After he won the election, McKinley viewed the red carnation as a good luck charm. He wore one on his lapel regularly and soon began his custom of presenting them to visitors. He wore one during his fourteen years in Congress, his two gubernatorial wins and both 1896 and 1900 presidential campaigns.

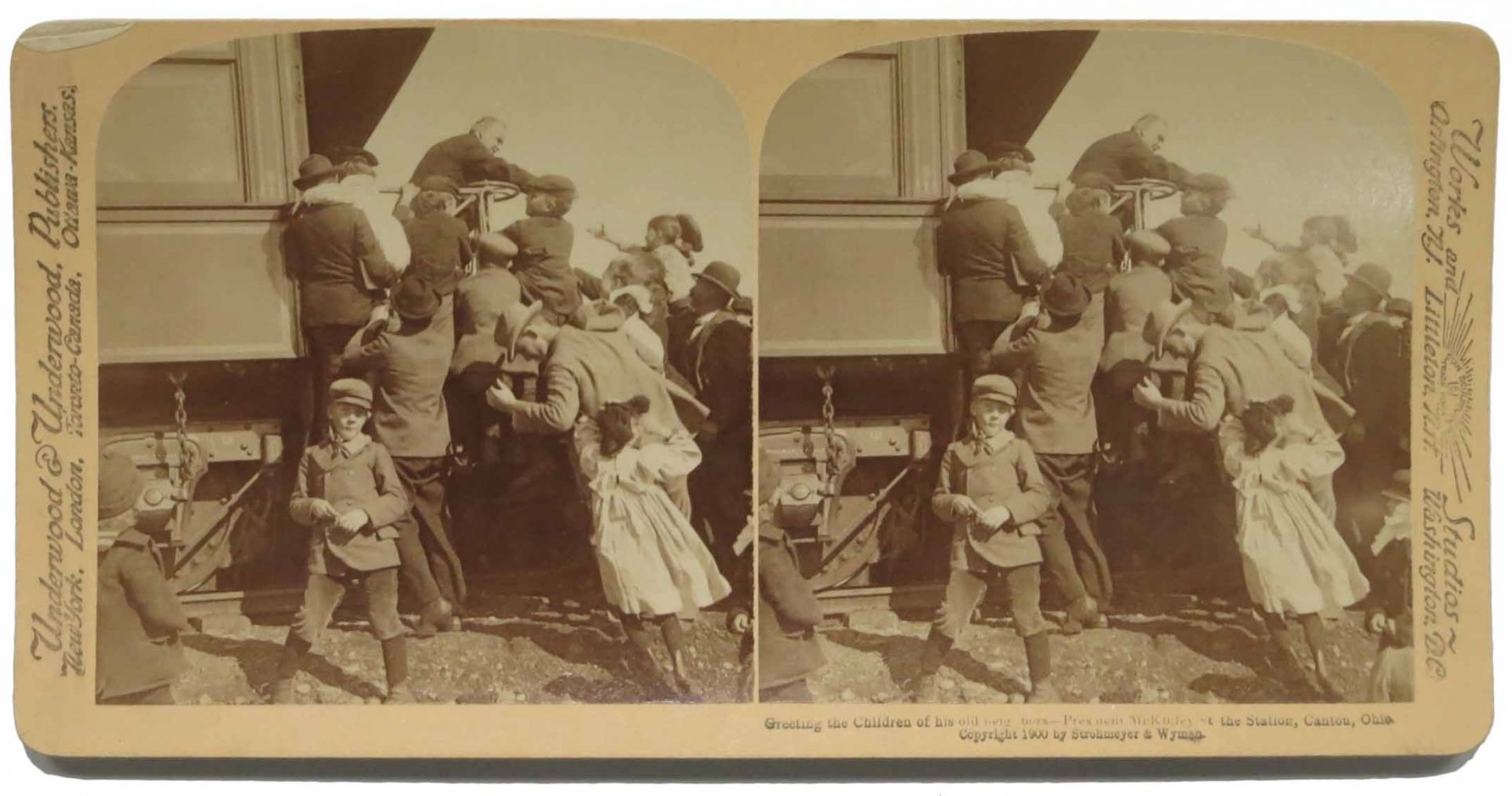

After his second inauguration on March 4, 1901, William and Ida McKinley departed on a six-week train trip of the country. The McKinleys were to travel through the South to the Southwest, and then up the Pacific coast and back east again, to conclude with a visit to the Buffalo Exposition on June 13, 1901. However, the First Lady fell ill in California, causing her husband to limit his public events and cancel a series of planned speeches. The First family retreated to Washington for a month and then traveled to their Canton, Ohio home for another two months, delaying the Expo trip until September.

After his second inauguration on March 4, 1901, William and Ida McKinley departed on a six-week train trip of the country. The McKinleys were to travel through the South to the Southwest, and then up the Pacific coast and back east again, to conclude with a visit to the Buffalo Exposition on June 13, 1901. However, the First Lady fell ill in California, causing her husband to limit his public events and cancel a series of planned speeches. The First family retreated to Washington for a month and then traveled to their Canton, Ohio home for another two months, delaying the Expo trip until September.

As McKinley fell backwards into the arms of his aides, members of the crowd immediately attacked Czolgosz. McKinley said, “Go easy on him, boys.” McKinley urged his aides to break the news gently to Ida, and to call off the mob that had set on Czolgosz, thereby saving his assassin’s life. McKinley was taken to the Exposition aid station, where the doctor was unable to locate the second bullet. Ironically, although a newly developed X-ray machine was displayed at the fair, doctors were reluctant to use it on the President because they did not know what side effects. Worse yet, the operating room at the exposition’s emergency hospital did not have any electric lighting, even though the exteriors of many of the buildings were covered with thousands of light bulbs. Amazingly, doctors used a pan to reflect sunlight onto the operating table as they treated McKinley’s wounds.

As McKinley fell backwards into the arms of his aides, members of the crowd immediately attacked Czolgosz. McKinley said, “Go easy on him, boys.” McKinley urged his aides to break the news gently to Ida, and to call off the mob that had set on Czolgosz, thereby saving his assassin’s life. McKinley was taken to the Exposition aid station, where the doctor was unable to locate the second bullet. Ironically, although a newly developed X-ray machine was displayed at the fair, doctors were reluctant to use it on the President because they did not know what side effects. Worse yet, the operating room at the exposition’s emergency hospital did not have any electric lighting, even though the exteriors of many of the buildings were covered with thousands of light bulbs. Amazingly, doctors used a pan to reflect sunlight onto the operating table as they treated McKinley’s wounds. McKinley drifted in and out of consciousness all day. By evening, McKinley himself knew he was dying, “It is useless, gentlemen. I think we ought to have prayer.” Relatives and friends gathered around the deathbed. The First Lady sobbed over him, “I want to go, too. I want to go, too.” Her husband replied, “We are all going, we are all going. God’s will be done, not ours” and with final strength put an arm around her. Some reports claimed that he also sang part of his favorite hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee” while others claim that the First Lady sang it softly to him. At 2:15 a.m. on September 14, President McKinley died. Czolgosz was sentenced to death and executed by electric chair on October 29, 1901.

McKinley drifted in and out of consciousness all day. By evening, McKinley himself knew he was dying, “It is useless, gentlemen. I think we ought to have prayer.” Relatives and friends gathered around the deathbed. The First Lady sobbed over him, “I want to go, too. I want to go, too.” Her husband replied, “We are all going, we are all going. God’s will be done, not ours” and with final strength put an arm around her. Some reports claimed that he also sang part of his favorite hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee” while others claim that the First Lady sang it softly to him. At 2:15 a.m. on September 14, President McKinley died. Czolgosz was sentenced to death and executed by electric chair on October 29, 1901. Loyal readers will recognize my affinity for objects and will not be surprised by the query, “What became of that assassination carnation?” In an article for the Massillon, Ohio Daily Independent newspaper on Sept. 7, 1984, Myrtle Ledger Krass, the 12-year-old-girl to whom the President gave his lucky flower moments before he was killed, reported that the McKinley’s carnation was pressed and kept in the family Bible. Myrtle, at the time a well-known painter living in Largo, Florida, explained how, many years later while moving, “The old Bible had been put away for years, when I took it out to wrap it for moving, it just crumbled in my hand. Just fell away to nothing.”

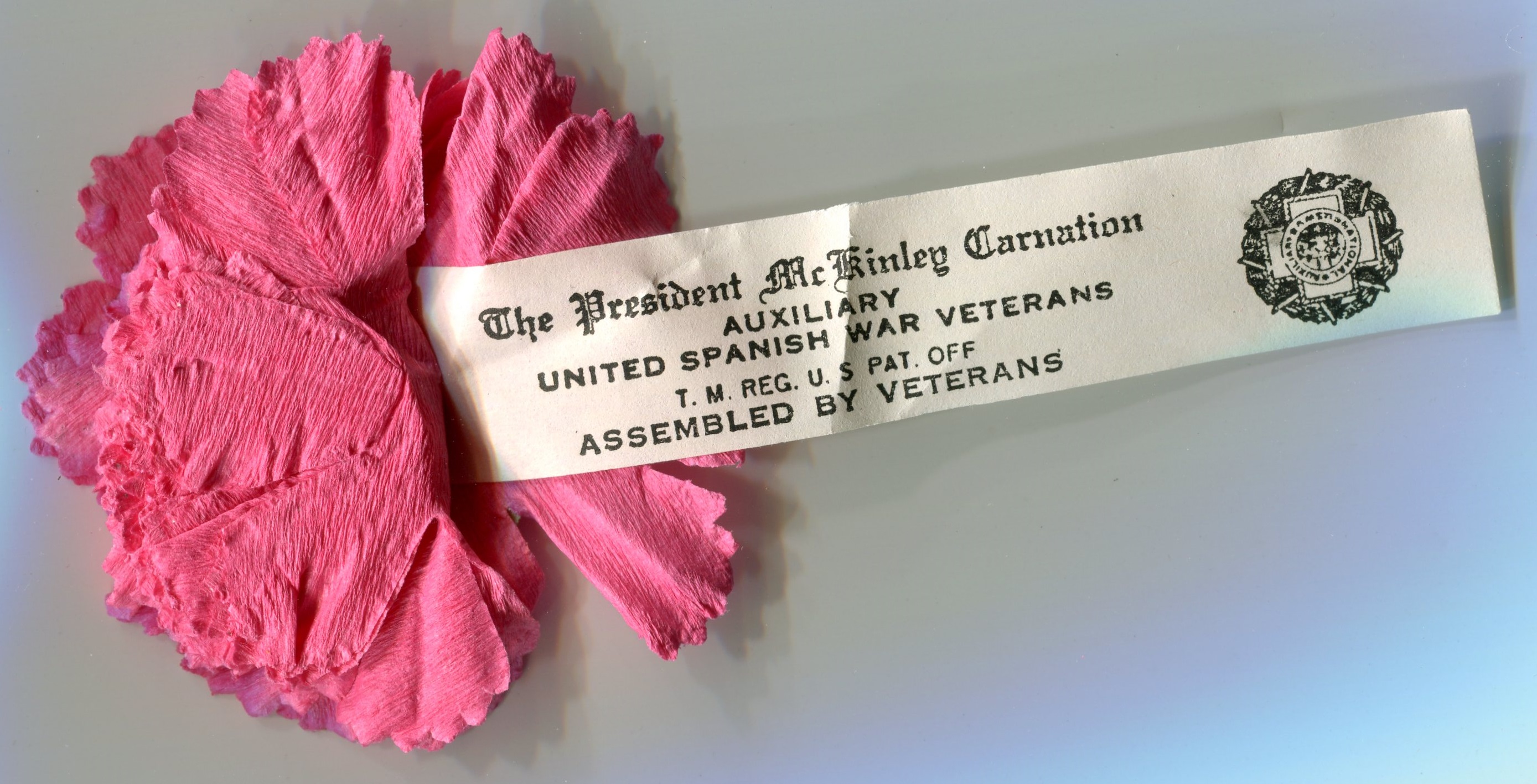

Loyal readers will recognize my affinity for objects and will not be surprised by the query, “What became of that assassination carnation?” In an article for the Massillon, Ohio Daily Independent newspaper on Sept. 7, 1984, Myrtle Ledger Krass, the 12-year-old-girl to whom the President gave his lucky flower moments before he was killed, reported that the McKinley’s carnation was pressed and kept in the family Bible. Myrtle, at the time a well-known painter living in Largo, Florida, explained how, many years later while moving, “The old Bible had been put away for years, when I took it out to wrap it for moving, it just crumbled in my hand. Just fell away to nothing.” In 1902, Lewis Gardner Reynolds (born in 1858 in Bellefontaine, Ohio) found himself in Buffalo on business on the first anniversary of McKinley’s death. While there he found that the mayor of Buffalo had declared the day a legal holiday. Gardner recalled, “without thinking at the time that I was doing something that would become a national custom, I purchased a pink carnation which I placed in the buttonhole of my coat after tying a small piece of black ribbon on it. As I went through Buffalo I explained to questioners the reason for the flower and the black ribbon. Many of those who questioned me followed my example.” On his return to Ohio, he explained to his friend Senator Mark Hannah what he had done in Buffalo. Later, in Cleveland, Reynolds met with Hannah and Governor Myron T. Herrick. Soon plans were made to celebrate Jan. 29, the anniversary of McKinley’s birth, as “Carnation Day.”

In 1902, Lewis Gardner Reynolds (born in 1858 in Bellefontaine, Ohio) found himself in Buffalo on business on the first anniversary of McKinley’s death. While there he found that the mayor of Buffalo had declared the day a legal holiday. Gardner recalled, “without thinking at the time that I was doing something that would become a national custom, I purchased a pink carnation which I placed in the buttonhole of my coat after tying a small piece of black ribbon on it. As I went through Buffalo I explained to questioners the reason for the flower and the black ribbon. Many of those who questioned me followed my example.” On his return to Ohio, he explained to his friend Senator Mark Hannah what he had done in Buffalo. Later, in Cleveland, Reynolds met with Hannah and Governor Myron T. Herrick. Soon plans were made to celebrate Jan. 29, the anniversary of McKinley’s birth, as “Carnation Day.”

Today, the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus continues observing Red Carnation Day every January 29 by installing a small display honoring the assassinated President. Last year, the Statehouse Museum Shop and on-site restaurant offered special discounts to anyone wearing a red carnation or dressed in scarlet on that day. Yes, the sentimental association of the carnation with McKinley’s memory is due to Lewis Gardner Reynolds.

Today, the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus continues observing Red Carnation Day every January 29 by installing a small display honoring the assassinated President. Last year, the Statehouse Museum Shop and on-site restaurant offered special discounts to anyone wearing a red carnation or dressed in scarlet on that day. Yes, the sentimental association of the carnation with McKinley’s memory is due to Lewis Gardner Reynolds.

He also shared stories of the Lone Ranger from movie, television and real life. “The closest I ever got to the part was in 1945 when I played Little Beaver with Wild Bill Elliott in the Red Ryder serial “Lone Texas Ranger.” Blake said, “I always modeled Little Beaver after Tonto you know.” Keep in mind, this was WAY before Google in an age when these tidbits were only known to the participants. It was Robert Blake who first told me the true story of the Lone Ranger.

He also shared stories of the Lone Ranger from movie, television and real life. “The closest I ever got to the part was in 1945 when I played Little Beaver with Wild Bill Elliott in the Red Ryder serial “Lone Texas Ranger.” Blake said, “I always modeled Little Beaver after Tonto you know.” Keep in mind, this was WAY before Google in an age when these tidbits were only known to the participants. It was Robert Blake who first told me the true story of the Lone Ranger.

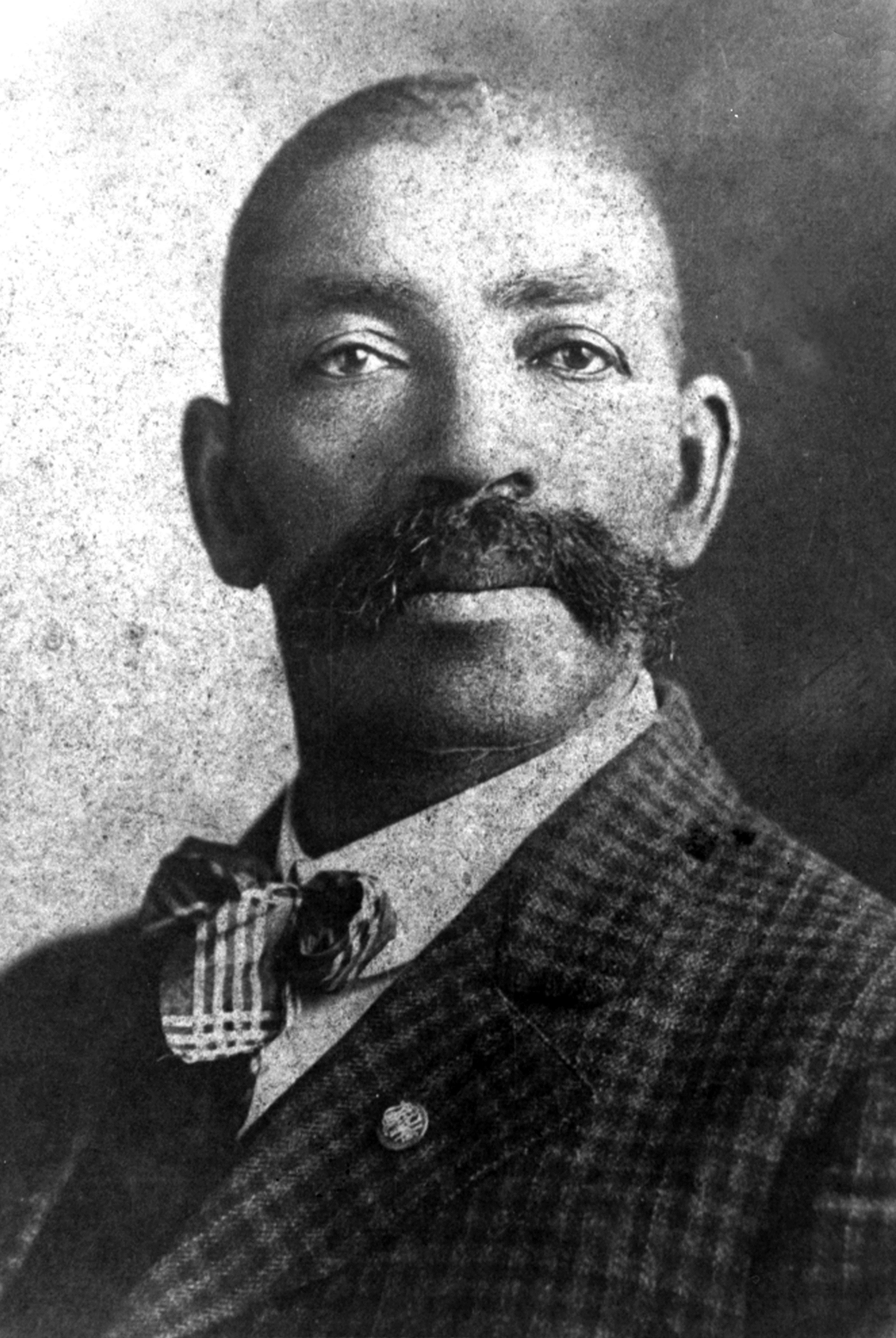

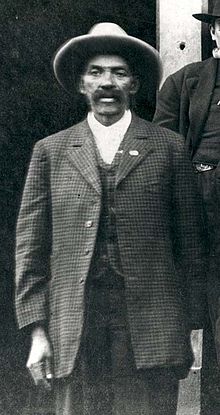

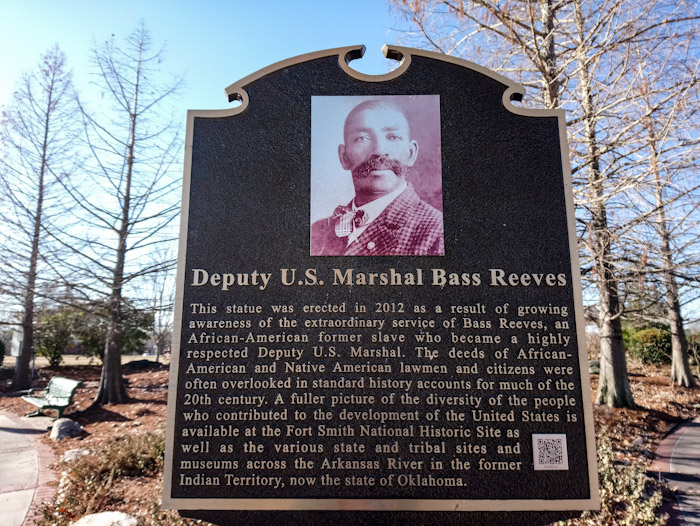

Reeves, born a slave in July of 1838, accompanied his “master” Arkansas state legislator William Steele Reeves’ son, Colonel George R. Reeves, as a personal servant when he went off to fight with the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Col. Reeves, of the CSA’s 11th Texas Cavalry Regiment, was a sheriff, tax collector, legislator, and a one-time Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives. During the Civil War, the Texas 11th Cavalry was involved in some 150 battles and skirmishes. Records are sketchy, but one report states that although 500 men served with the unit, less than 50 returned home at the end of the war.

Reeves, born a slave in July of 1838, accompanied his “master” Arkansas state legislator William Steele Reeves’ son, Colonel George R. Reeves, as a personal servant when he went off to fight with the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Col. Reeves, of the CSA’s 11th Texas Cavalry Regiment, was a sheriff, tax collector, legislator, and a one-time Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives. During the Civil War, the Texas 11th Cavalry was involved in some 150 battles and skirmishes. Records are sketchy, but one report states that although 500 men served with the unit, less than 50 returned home at the end of the war.

Ironically, Bass Reeves was himself once charged with murdering a posse cook. At his trial before Judge Parker, Reeves was represented by former United States Attorney W. H. H. Clayton, who had been his colleague and friend. Reeves was acquitted. On another instance, Reeves arrested his own son for murder. One of his sons, Bennie Reeves, was charged with the murder of his wife. Although understandably disturbed and shaken by the incident, Deputy Marshal Reeves nonetheless demanded the responsibility of bringing Bennie to justice. Bennie was eventually tracked and captured, tried, and convicted. He served his time in Fort Leavenworth in Kansas before being released, and reportedly lived the rest of his life as a responsible and model citizen.

Ironically, Bass Reeves was himself once charged with murdering a posse cook. At his trial before Judge Parker, Reeves was represented by former United States Attorney W. H. H. Clayton, who had been his colleague and friend. Reeves was acquitted. On another instance, Reeves arrested his own son for murder. One of his sons, Bennie Reeves, was charged with the murder of his wife. Although understandably disturbed and shaken by the incident, Deputy Marshal Reeves nonetheless demanded the responsibility of bringing Bennie to justice. Bennie was eventually tracked and captured, tried, and convicted. He served his time in Fort Leavenworth in Kansas before being released, and reportedly lived the rest of his life as a responsible and model citizen.