Original publish date June 6, 2024. https://weeklyview.net/2024/06/06/leopold-and-loeb-a-hundred-years-on/

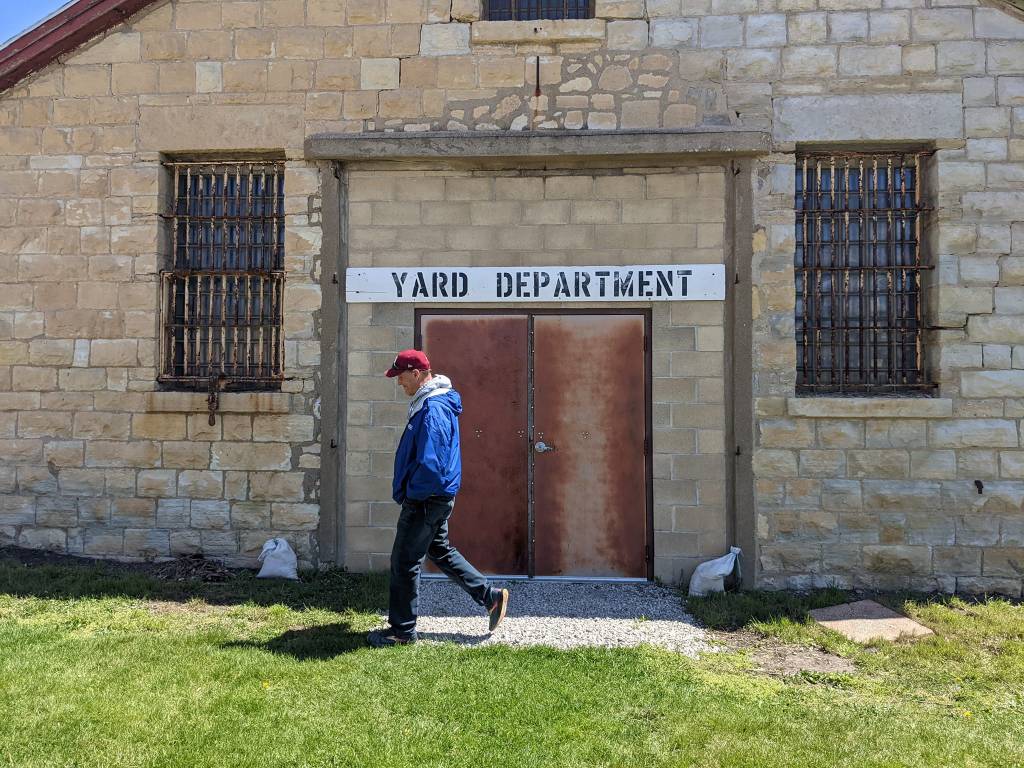

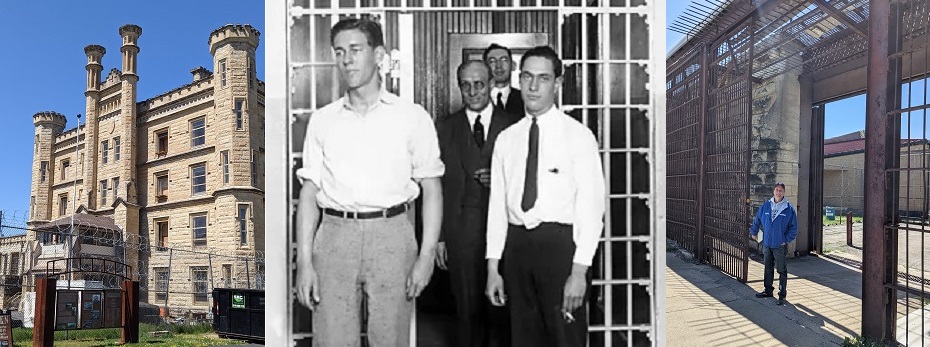

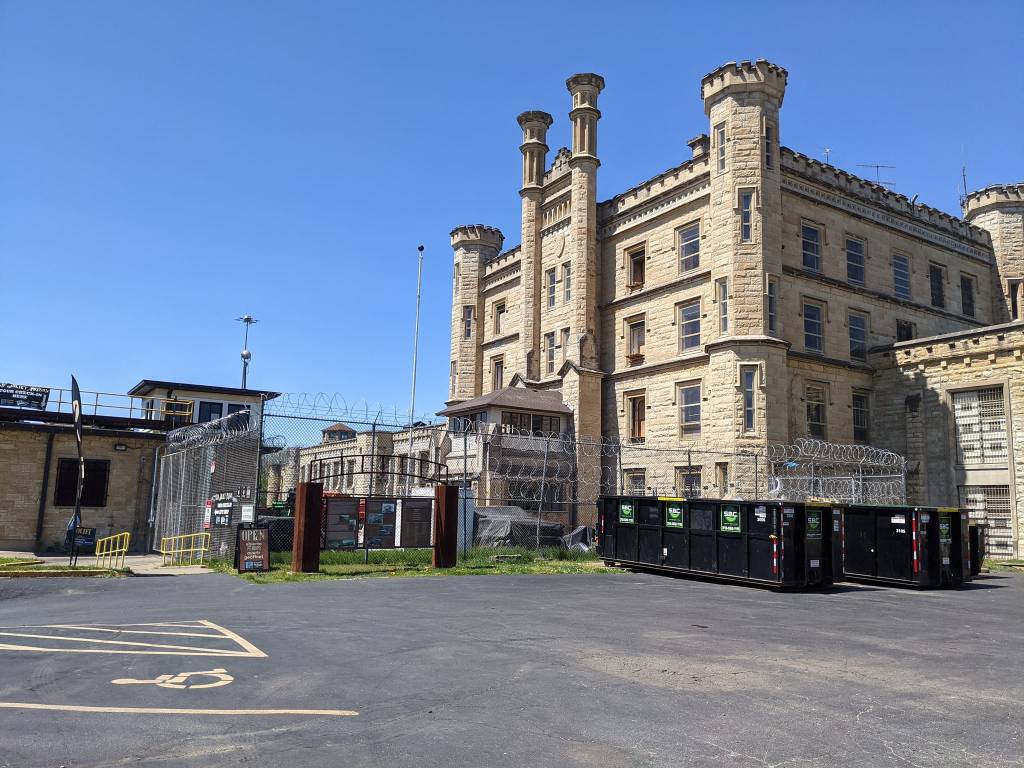

Last month, Rhonda and I drove to the outskirts of Chicago to visit Joliet Prison in Illinois. Like many ancient jails, prisons, and penitentiaries, Joliet has experienced a second life as a tourist attraction. It opened back in 2018. During the summer months (June to September) Joliet is open daily for tours until 6 p.m. For $20 you can go visit the old stomping grounds of notorious inmates like Richard Speck, John Wayne Gacy, James Earl Ray, and Baby Face Nelson. In my case, I was interested in the place because of Leopold and Loeb. Okay, okay, I was also there thinking of the Blues Brothers, but mostly Leopold and Loeb.

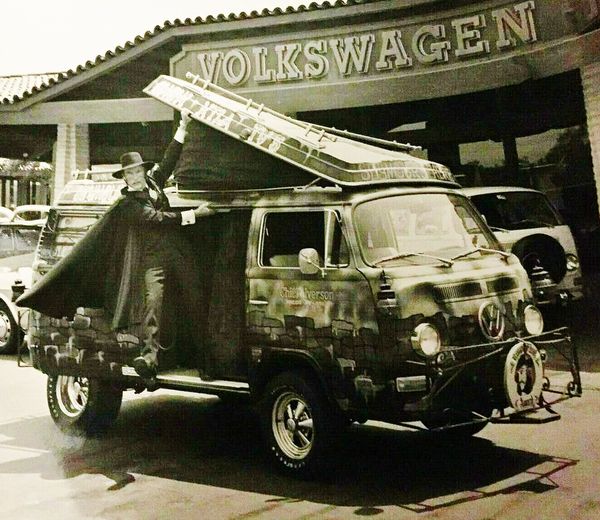

Old Joliet Penitentiary (originally known as Illinois State Penitentiary) opened in 1858 and was a working prison until 2002. In “The Blues Brothers” movie, Dan Aykroyd (Elwood J. Blues) awaits outside the prison gate for the release of John Belushi’s character (“Joliet Jake” Blues). Guests enter through the same gate Belushi exits. If you are sly, you can sneak over and crank the gate open or closed on your own. The prison was also used in the cult classic James Cagney film “White Heat” and the 1957 movie “Baby Face Nelson.”

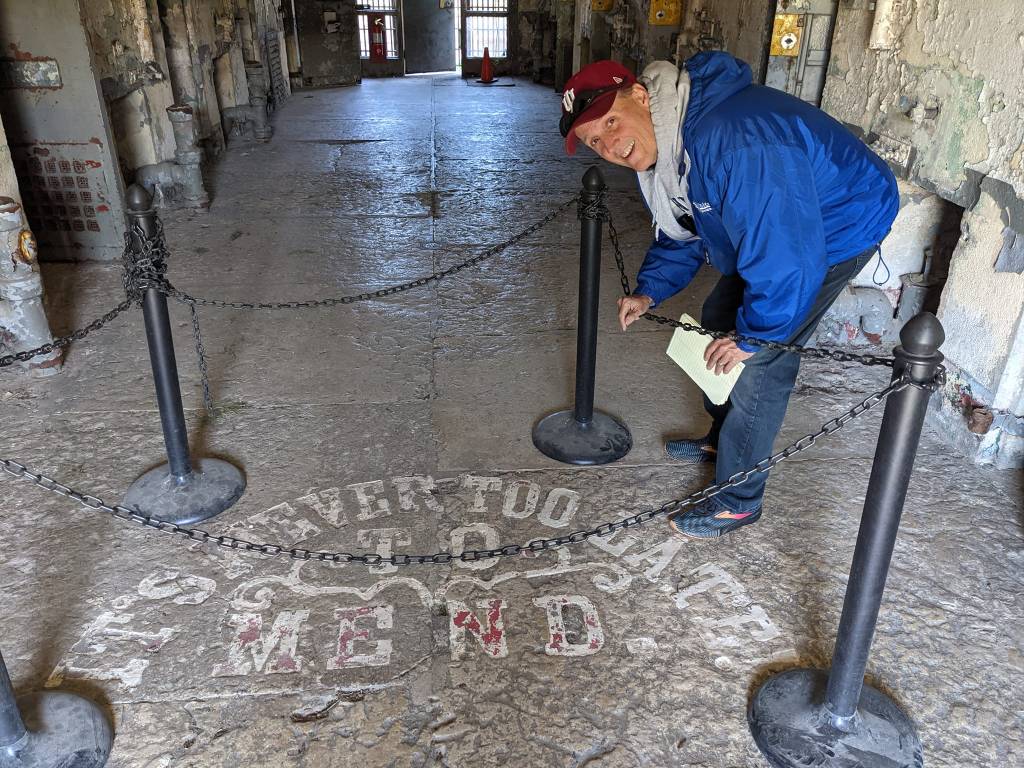

Like many of these incarceration-as-entertainment venues, Joliet is in a perpetual state of arrested decay. The tours are entirely self-guided and for a double sawbuck, you are handed a map and told to go explore “any door that is open.” We followed instructions and were only chased out of one building: the maintenance building. Which begged the question, “Then why did you leave the door open?” Visitors are warned not to shut the cell doors because they don’t have the keys and, oh, look out for rats. (For the record we saw none.) The women’s prison is still in place across the street but is only used nowadays for Halloween seasonal haunted houses and ghost tours.

Why, you ask, Leopold and Loeb? Well, because it was the 100th anniversary date of a crime that is mostly forgotten today but was the first “Crime of the Century”, the first “Trial of the Century” and the first “Media Circus” this “country-as-world-superpower” ever experienced. Fresh off the victory in World War I and smack dab in the middle of the Jazz Age, everything was bigger, faster, and more important in the US at the time. The crime hit the USA like a Jack Dempsey knockout punch to the jaw.

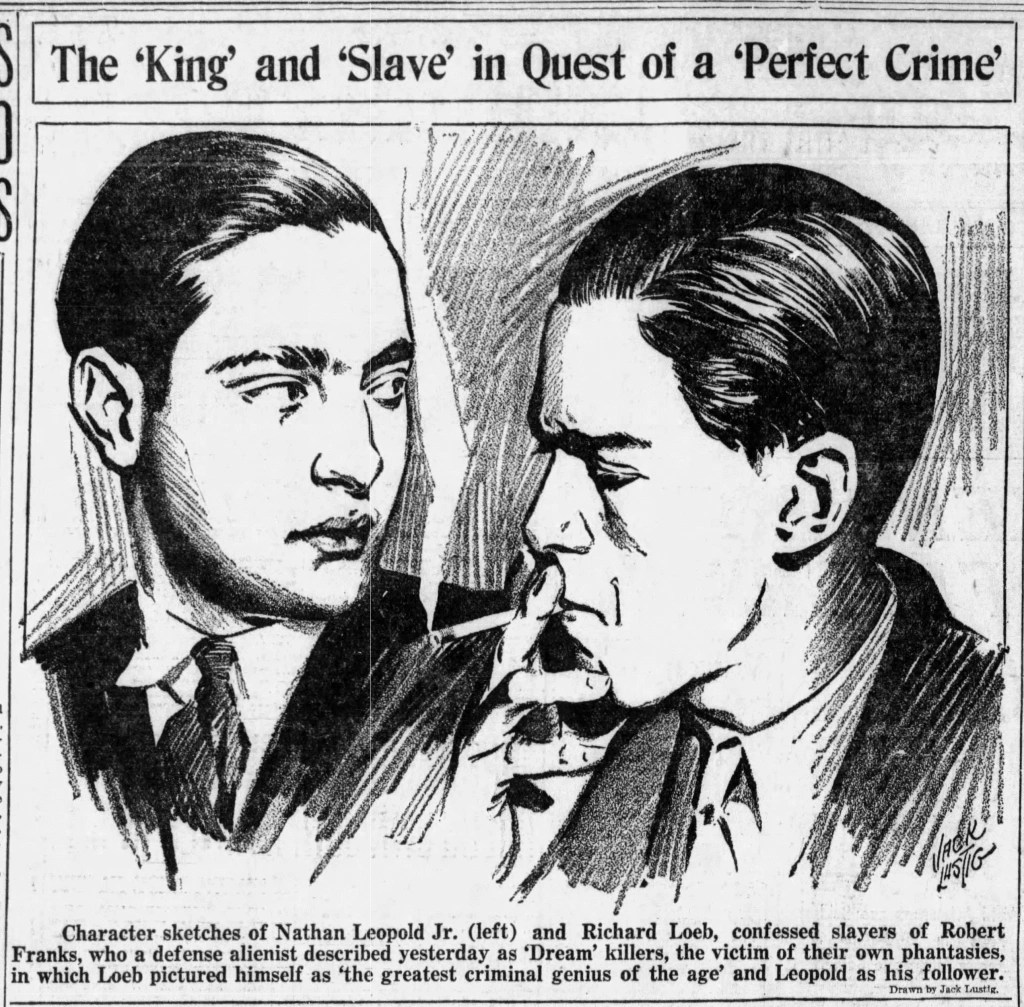

Nathan Freudenthal Leopold Jr. (November 19, 1904 – August 29, 1971) and Richard Albert Loeb (June 11, 1905 – January 28, 1936), were two affluent students at the University of Chicago who kidnapped and murdered a Chicago boy named Bobby Franks on May 21, 1924. They disposed of the schoolboy’s body in a culvert along the muddy shore of Wolf Lake in Hammond, Indiana. The duo committed the country’s first “thrill kill” as a demonstration of their superior intellect, believing it to be the perfect crime without possible consequences.

Leopold (19) and Loeb (18) settled on identifying, kidnapping, and murdering a younger adolescent as their perfect crime. They spent seven months planning everything, from the method of abduction to purchasing rope and a heavy chisel to use as weapons, and to the disposal of the body. To make sure each of them was equally culpable in the murder, they agreed to wrap the rope around their victim’s neck and then each would pull equally on their end, strangling him to death. To hide the casual nature of their “thrill kill” motive, they decided that they had to make a ransom demand, even though neither teenager needed the money.

After a lengthy search in the Kenwood area, on the shore of Lake Michigan on the South Side of Chicago, they found a suitable victim on the grounds of the Harvard School for Boys where Leopold had been educated. (Today, Kenwood has received national attention as the home of former President Barack Obama and his family.) The duo decided on 14-year-old Robert “Bobby” Franks, the son of wealthy Chicago watch manufacturer Jacob Franks. Bobby lived across the street from Loeb and had played tennis at the Loeb residence many times before.

Around 5:15 on the evening of May 21, 1924, using a rented automobile, Leopold and Loeb offered Franks a ride as he walked home from school after a baseball game. Since Bobby was hesitant, being less than two blocks from his home (which still stands at 5052 S. Ellis), Loeb told the victim he wanted to talk to Bobby about a tennis racket that he had been using. While the exact details of the crime are in dispute, it is believed that Leopold was behind the wheel of the car with Bobby in the passenger seat while Loeb sat in the back seat with the chisel. Loeb struck Franks in the head from behind several times with the chisel, then dragged him into the back seat and gagged him, where he died.

Loeb stuffed the boy’s body into the floorboards and scrambled over the back of the passenger seat. There is little doubt that the deadly duo’s demeanor was joyous as they exchanged smiles below bulging eyes accentuated with anxious breathing and giggles of laughter. The men drove to their predetermined body-dumping spot near Wolf Lake in Hammond, 25 miles south of Chicago. They concealed the body in a culvert along the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks north of the lake. To hinder identification, they poured hydrochloric acid on the face and body. When they returned to Chicago, they typed a ransom note, burnt their blood-stained clothing, and cleaned the blood stains from the rented vehicle’s upholstery. After which, they spent the remainder of the evening playing cards. They didn’t know that police had found a pair of Leopold’s prescription eyeglasses (one of only three such pairs in the entire city) near Franks’ body.

Their plan unraveled quickly. When Roby, Indiana, (a now non-existent neighborhood west of Hammond) resident Tony Minke discovered the bundled-up body of Bobby Franks along the shore of Wolf Lake, the gig was up. The thrill killers destroyed the typewriter and burned the lap blanket used to cover the body and then casually resumed their lives as if nothing ever happened. Both of these demented little rich boys enjoyed chatting with friends and family members about the murder. Leopold discussed the case with his professor and a girlfriend, joking that he would confess and give her the reward money. Loeb, when asked to describe Bobby by a reporter, replied: “If I were to murder anybody, it would be just such a cocky little S.O.B. as Bobby Franks.” When asked to explain how the eyeglasses got there, Leopold said that they might have fallen out of his pocket during a bird-watching trip the weekend before. Leopold and Loeb were summoned for formal questioning on May 29. Loeb was the first to crack. He said Leopold had planned everything and had killed Franks in the back seat of the car while he drove. Once informed of Loeb’s confession, Leopold insisted that he was the driver and Loeb the murderer. The confessions were announced by the state’s attorney on May 31, 1924.

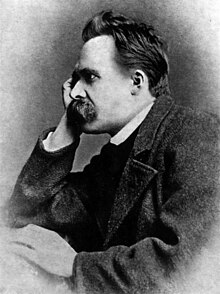

Later, both admitted that they were driven to commit a “perfect crime” by Übermenschen (supermen) delusions, and their thrill-seeking mentalities drove a warped interest to learn what it would feel like to be a murderer. While it is true that Leopold and Loeb knew each other only casually while growing up, their relationship flourished at the University of Chicago. Their sexual relationship began in February 1921 and continued until the pair were arrested. Leopold was particularly fascinated by Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of Übermenschen, interpreting themselves as transcendent individuals possessing extraordinary, superhuman capabilities whose superior intellects would allow them to rise above the laws and rules that bound the unimportant, average populace.

Early in their relationship, Leopold convinced Loeb that if they simply adhered to Nietzsche’s doctrines, they would not be bound by any of society’s normal ethics or rules. In a letter to Loeb, he wrote, “A superman … is, on account of certain superior qualities inherent in him, exempted from the ordinary laws which govern men. He is not liable for anything he may do.” The duo first tested their theory of perceived exemption from normal restrictions with acts of petty theft and vandalism including breaking into a University of Michigan fraternity house to steal penknives, a camera, and the typewriter later used to type the ransom note. Emboldened, they progressed to arson, but no one seemed to notice. Disappointed with the lack of media coverage of their crimes, they began to plan and execute a sensational “perfect crime” to grab the public’s attention and cement their self-perceived status as “supermen”.

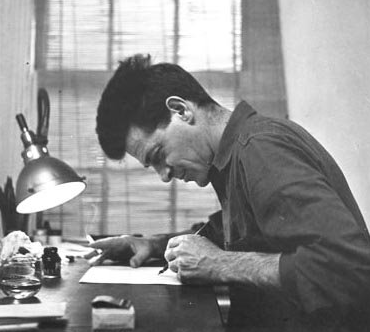

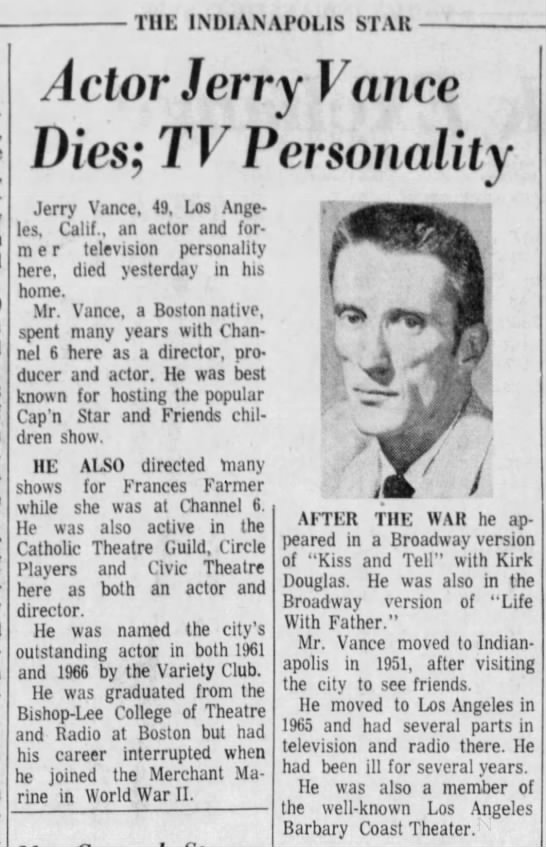

After the two men were arrested, Loeb’s family retained Clarence Darrow as lead counsel for their defense. Clarence Seward Darrow (April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was perhaps the most famous lawyer of the late 19th / early 20th centuries. He was known for his strenuous defense of women, Civil Rights, early trade unions, and the Scopes “monkey” trial. Darrow was also a well-known public speaker, debater, and writer. He took the case because he was a staunch opponent of capital punishment. Darrow’s father was an ardent abolitionist and his mother was an early supporter of female suffrage and women’s rights.

The trial took place at Chicago’s Cook County Criminal Courthouse. For his efforts, Darrow was paid $65,000 (equivalent to $1,200,000 today). Everyone expected the defense would be not guilty because of insanity, but Darrow believed that a jury trial would convict his clients and impose the death penalty regardless of the plea. So Darrow entered a plea of guilty and appealed to Judge John R. Caverly to impose life sentences instead. The sentencing hearing ran for 32 days. The state presented over 100 witnesses, meticulously documenting the crime. The defense presented extensive psychiatric testimony to establish mitigating circumstances, including childhood neglect in the form of absent parenting, and in Leopold’s case, sexual abuse by a governess. But it was Darrow’s impassioned, eight-hour-long “masterful plea” after the hearing (called the finest speech of his career) that saved Leopold and Loeb’s lives. Darrow argued that the methods and punishments of the American justice system were inhumane, and the youth and immaturity of the accused should be considered in their sentencing.

Darrow’s speech, at least in part, is worth revisiting here. “Is any blame attached because somebody took Nietzsche’s philosophy seriously and fashioned his life upon it? It is hardly fair to hang a 19-year-old boy for the philosophy that was taught him at the university…Your Honor knows that in this very court crimes of violence have increased growing out of the war. Not necessarily by those who fought but by those that learned that blood was cheap, and human life was cheap, and if the State could take it lightly why not the boy?…The easy thing and the popular thing to do is to hang my clients. I know it. Men and women who do not think will applaud…(I) would ask that the shedding of blood be stopped, and that the normal feelings of man resume their sway. Your Honor stands between the past and the future. You may hang these boys; you may hang them by the neck until they are dead. But in doing it you will turn your face toward the past. In doing it you are making it harder for every other boy who in ignorance and darkness must grope his way through the mazes which only childhood knows. In doing it you will make it harder for unborn children. You may save them and make it easier for every child that sometime may stand where these boys stand. You will make it easier for every human being with an aspiration and a vision and a hope and a fate. I am pleading for the future; I am pleading for a time when hatred and cruelty will not control the hearts of men. When we can learn by reason and judgment and understanding and faith that all life is worth saving, and that mercy is the highest attribute of man.”

Both men were sentenced to life plus 99 years. During Darrow’s month-long courtroom argument to save their lives, Leopold and Loeb’s families greased the guards with bribes to soften their stay at the Cook County Jail. That abruptly ended when they reached Joliet. The Illinois State Penitentiary was already out of date and seriously overcrowded when they arrived. It had been condemned as unfit for habitation twenty years prior, yet, was still open. According to the Joliet Prison website, “Built in 1858 of limestone quarried on the site by prisoners to house 900 inmates; by 1924 over 1,800 prisoners were incarcerated there. The cells, four feet by eight, were damp, had narrow slits for windows, and possessed no plumbing: prisoners were given a jug of water each morning and made do with a bucket to use as a toilet. Every aspect of life at Joliet was regulated. Prisoners were given two changes of underwear, blue shirts, pants, socks, and heavy shoes to use each week. Contact with the outside world was limited. Inmates could send a single letter and receive visitors every second week. Using funds from their prison accounts, they could purchase tobacco, rolling papers, chewing gum, and candy from the prison commissary. There were no other privileges. A bell awoke prisoners at 6:30 AM and the cell blocks filled with sounds of locks opening, doors slamming shut, and boots marching along the steel flooring. After dressing, inmates grabbed the buckets and carried them into the courtyard, emptying their refuse into a rancid trough. Meals were served in a large dining hall; twice a week prisoners had beef stew for breakfast; other days hash was served. The food was cold and unappealing, sitting in pools of congealed fat on aluminum trays.”

As the Medieval prison loomed before them, its towers bathed in the glow of arc lights shadowing what lay behind the walls, the two convicted killers surely swallowed hard in fear. Thanks to the specialized skills of attorney Darrow, they had escaped the death penalty only to find themselves condemned to life imprisonment in this foreboding fortress. Leopold and Loeb were introduced to their new life at the Illinois State Penitentiary at Joliet on the night of September 11, 1924. Bound in ankle chains tethered by a chain to their handcuffs, the duo shuffled through the front gates of the inmate reception area. By the next day, their heads were shaved; they were photographed and fingerprinted; authorities assigned them prison numbers: Leopold was Inmate No. 9305, and Loeb No. 9306. After processing, they were led to separate cells, disappearing into the penitentiary population. Once they entered regular prison life, they were kept in solitary cells for several months, both because of the publicity of their crime and also because they were among the youngest inmates of the prison. Although kept apart as much as possible, the two managed to maintain their friendship. Leopold and Loeb spent most of their days working in prison shops: Leopold wove rattan chair bottoms in the prison’s Fibre Shop, while Loeb constructed furniture. Between meals, they were allowed two fifteen-minute breaks in which to walk or smoke. After dinner at four, they returned to their cells. At nine, lights out.