Part II

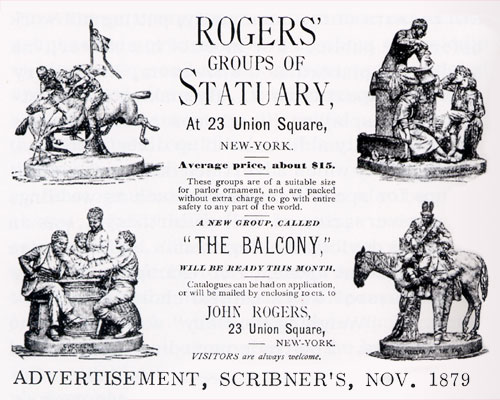

If you are a fan of Victorian decor, or if, like me, you find yourself haunting antique malls and shops, you’re probably familiar with the work of sculptor John Rogers. Commonly known as “Groups” for their routine use of more than one subject per sculpture, Rogers’ work is distinctive for many reasons: historical themes, uncommon accuracy and exquisite detail. Rogers was the first American sculptor to be classified as a “pop artist”, scorned by art critics but beloved by the average American. His themes included literary themes, Civil War soldiers, ordinary citizens, animals, sports and luminaries from the pages of history. For Irvingtonians, his works depicting namesake Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle are particularly prized.

John Rogers Rip Van Winkle Series.

I have a few in my office and one of my favorite places to eat, the “Back 40 Junction” in Decatur, is decorated with many John Rogers groups throughout their restaurant.

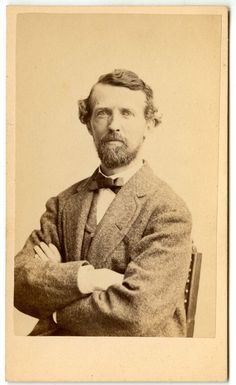

John Rogers was born in Salem, Massachusetts, on October 30, 1829, how can Halloween fans not love him already? His father, an unsuccessful but well-connected Boston merchant, felt that an artist’s life was no better than a vagabond and discouraged his artistic son from pursuing art as a profession. So, Rogers confined his love of drawing, painting and modeling in clay to his spare time. In 1856 Rogers ran away to Mark Twain’s Hannibal, Missouri where he worked as a railroad mechanic. Two years later, he moved to Europe to attain a formal education in sculpting. His first group, in 1859, he titled “The Slave Auction”. It depicts a white auctioneer as he gavels down the sale of a defiant black man, posed arms crossed, with his weeping wife and babies cowering at the side. Rogers, a strong abolitionist, was making a statement against slavery but New York shopkeepers refused to display his work in their windows for fear that the controversial subject matter would drive customers away. So Rogers hired a black salesman to peddle the statue from door-to-door and in a short time, Rogers’ statue, described as “Uncle Tom’s Cabin in plaster” became a best seller.

Sculptor John Rogers.

That same year, Rogers went to Chicago, where he entered his next statue, titled “The Checker Players” in a charity event, which won a $75.00 prize and attracted much attention. Rogers soon began rapidly producing very popular, relatively inexpensive figurines to satiate the average Gilded Age citizen’s thirst for art. Over the next quarter century, a total of 100,000 copies of nearly 90 different Rogers Groups were sold across the United States and abroad. Unsurprisingly, the next few years were filled with Rogers groups depicting scenes from the Civil War to honor their soldier boys serving far from home. These statues would remain popular with veterans after the war as well.

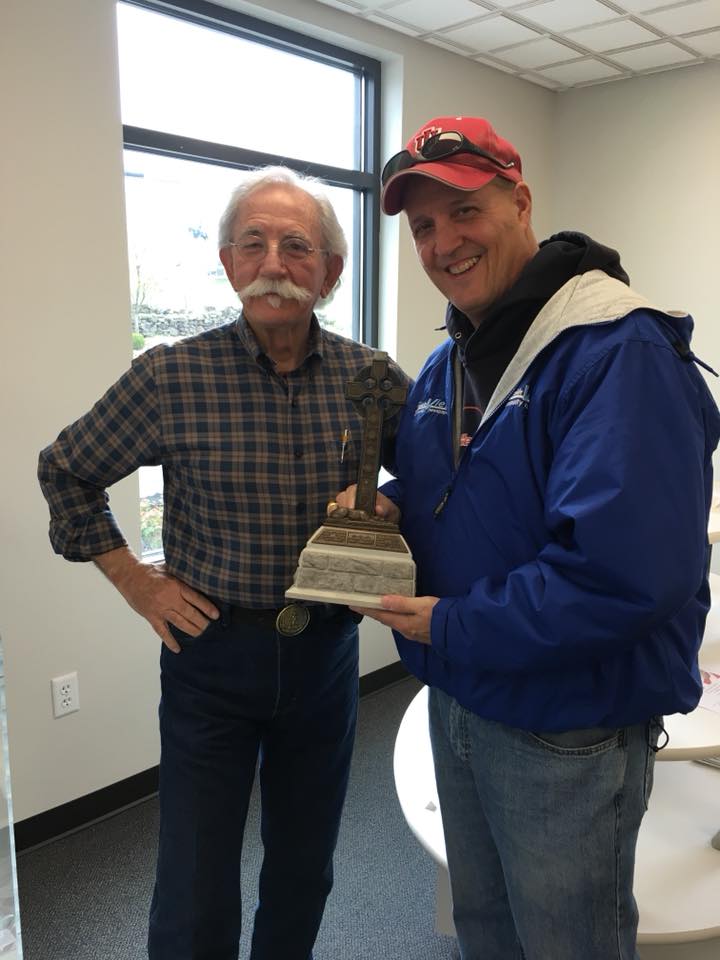

Gettysburg Longstreet monument sculptor Gary Casteel remarked, “Rogers is very well known as an American sculptor. More for his collection of small group settings rather than large public works. Both are excellent in detail and representation. His collection of CW related plaster cast pieces are quite well know and continually sought after by collectors to this day.” Rogers’ work was innovative, preferring to create his statuary based on every day, ordinary scenes from life. While Rogers’ work rarely made its way into art museums, it did grace the parlors, libraries and offices of Victorian homes around the world. However, there is one work that stands out among the rest, for subject matter, realism, and controversy.

“The Council of War”, created in 1868, stands 24 inches tall and, like all of Rogers’ groups, was designed to fit perfectly on a round oak “ball and claw” footed parlor table. It depicts Abraham Lincoln seated in a chair, studying a map held in both hands, as General Ulysses S. Grant and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton confer over his shoulders. The June 1872 issue of the “American Historical Record” describes the scene: “The time is supposed to be early in March, 1864, just after Grant was appointed a Lieutenant-General and entrusted by Congress with the largess and discriminatory power as General-in-Chief of all the armies. The occasion was the Council at which the campaign of 1864 was determined upon, which was followed by Grant’s order on the 1st of May for the advance of the great armies of the Republic against the principal forces of the Confederates.”

Gettysburg Sculptor Gary Casteel.

Both Robert Todd Lincoln and Edwin Stanton proclaimed this version of the President to be the best likeness of the man either had ever seen. Secretary Stanton wrote to the sculptor in May of 1872 stating, “I am highly gratified with the genius and artistic skill you have displayed. I think you were especially fortunate in your execution of the figure of President Lincoln. In form and feature it surpasses any effort to embody the expression of that great man which I have seen. The whole group is very natural and the work, like others from the same hand, well represents interesting incidents of the time.” Although the two surviving subjects received the piece positively, the public allegedly saw it differently: quite literally.

The controversy surrounding the pose arose based upon the positioning of Stanton behind Lincoln. Stanton, is posed polishing his spectacles, held in both hands, directly behind the President’s left ear approximately where Booth’s bullet entered Mr. Lincoln’s head. The pose is thought to have aroused the ire of collectors who believed the awkward positioning somehow stirred memories of the assassination. Hence, John Rogers made three versions of this particular group to appease those sympathies. Although the depictions of Grant and Lincoln remained the same in all three, Stanton’s hands were emptied and placed at his side in the second version and then changed back to polishing his glasses, this time forward of Lincoln’s head, in the third version. Some historians surmise the changes were affected due to the alleged theory of Stanton’s involvement in Lincoln’s murder that were circulating at the time. On the other hand, art historians claim the change was made for purely structural purposes and ease of casting to prevent breakage.

Modern day sculptors like Gary Casteel utilize many of the same methods as Rogers did a century-and-a-half ago, just as Rogers used those techniques he learned about while studying in Europe. Casteel, who like Rogers, also studied sculpture in Europe, says, “Every sculptor has his own way of sculpture production. However, there are probably similarities. I do a lot of detail as he did just simply because it’s my natural style.” The advantage that Gary Casteel has is the internet. Gary has a website and blog (Casteel Sculptures, LLC / Valley Arts Publishing) that walks his “fans” through the process of wood, wire & clay step-by-step. If you have an interest in the process, I highly recommend you subscribe to Gary’s blog. Watching Gary’s scale sculptures of the ornately detailed monuments of Gettysburg might better explain that Rogers’ changes in his Council of War group may not have been all about myth and urban legends after all.

At the height of their popularity, Rogers’ figurines graced the parlors of homes in the United States and around the world. Most sold for $15 apiece (about $450 in 2020 dollars), the figurines were affordable to the middle class. Instead of working in bronze and marble, he sculpted in more affordable plaster, painted the color of putty to hide dust. Rogers was inspired by popular novels, poems and prints as well as the scenes he saw around him. By the 1880s, it seemed that families who did not have a John Rogers Group were not conforming to the times. Even Abraham Lincoln owned a John Rogers Group. My favorite account of a typical Rogers statue encounter comes from the Great American West. Libby Custer mentions in her book “Boots and Saddles” that her husband, General George Armstrong Custer, carried two prized John Rogers groups (“One More Shot” and “Mail Day”, both depicting Civil War soldiers) from post-to-post on the Western frontier including the couples’ final Indian outpost before the “Last Stand.”

Libby and George Armstrong Custer.

Libby states, “Comparatively modern art was represented by two of the Rogers statuettes that we had carried about with us for years. Transportation for necessary household articles was often so limited it was sometimes a question whether anything that was not absolutely needed for the preservation of life should be taken with us, but our attachment for those little figures and the associations connected with them, made us study out a way always to carry them. At the end of each journey, we unboxed them ourselves, and sifted the sawdust through our fingers carefully, for the figures were invariably dismembered. My husband’s first occupation was to hang the few pictures and mend the statuettes. He glued on the broken portions and moulded (sic) putty in the crevices where the biscuit had crumbled. Sometimes he had to replace a bit that was lost… On one occasion we found the head of the figure entirely severed from the trunk. Nothing daunted, he fell to patching it up again… The distorted throat, made of unwieldy putty, gave the formally erect, soldierly neck a decided appearance of goiter. My laughter discouraged the impromptu artist, who for one moment felt that a “restoration” is not quite equal to the original. He declared that he would put a coat of gray paint overall, so that in a dim corner they might pass for new. I insisted that it should be a very dark corner!”

Another article, this one from the January 1926 issue of “Antiques” magazine, encapsulates the love-hate relationship for Rogers’ work: “The fact that Rogers groups are fragile has made them rare enough to arouse the interest of collectors, although I doubt that they will ever be widely collected or will ever acquire high values. They are too large to be comfortably collected in quantity. Nevertheless there might be some slight activity in Rogers groups among collectors of American antiques and it is to be hoped that existing examples will be preserved for the sake of what they express of life some forty years since.”

In 1878 Rogers opened a small studio at 13 Oenoke Ridge in New Canaan, Connecticut. By the 1890s, his work had largely fallen out of favor. Poor health forced his retirement in 1893. Rogers died at his New Canaan home on July 26, 1904. His studio was designated a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1965. Rogers sculpted what he saw, drawing his inspiration from the everyday beauty observed by his own eye or that created by his mind’s eye while interpreting the literary works he valued most. Although he died in relative obscurity, his works live on as perfect representations of Victorian Era life at the crossroads of the Gilded Age and the Second Industrial Revolution.

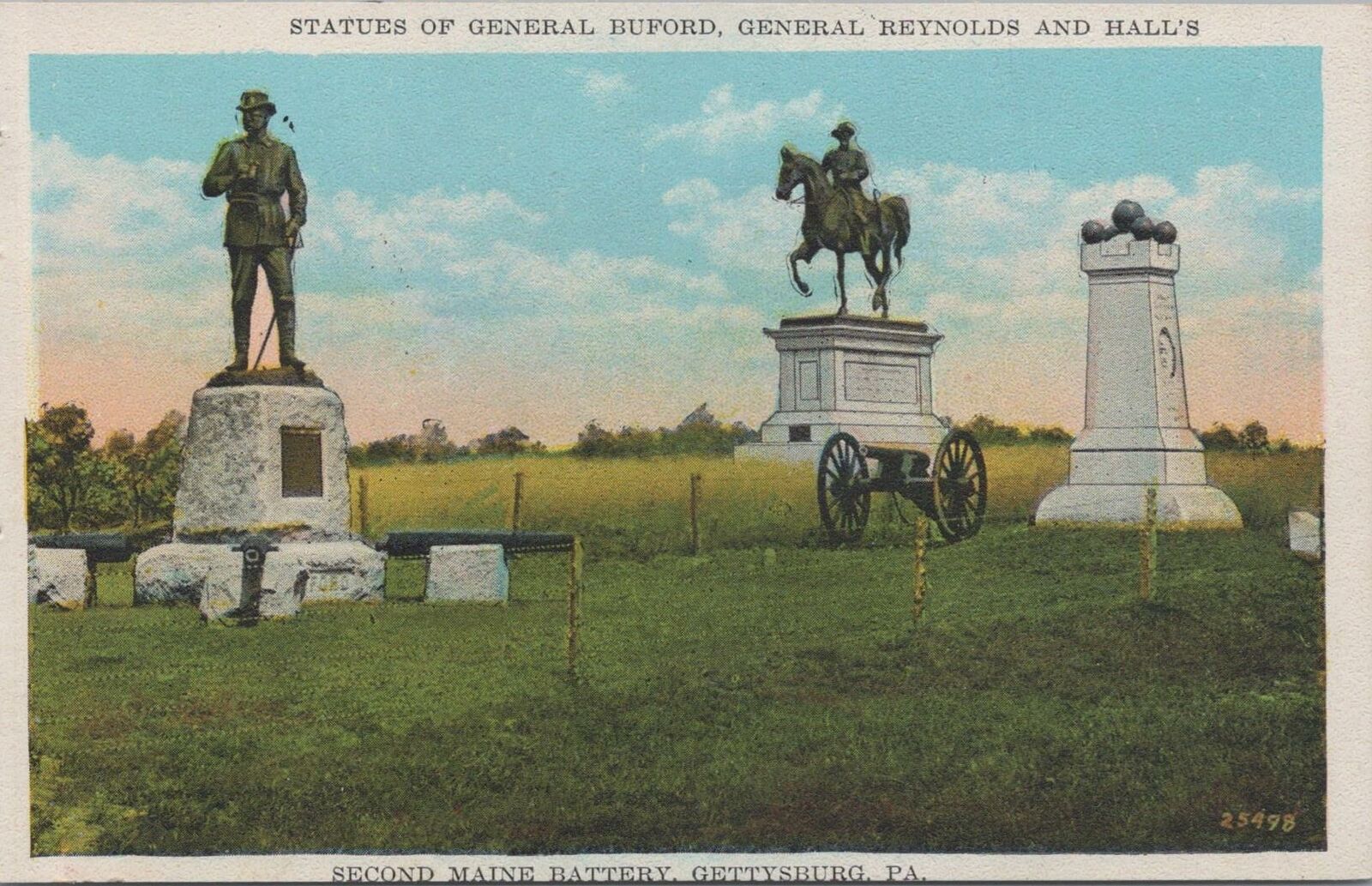

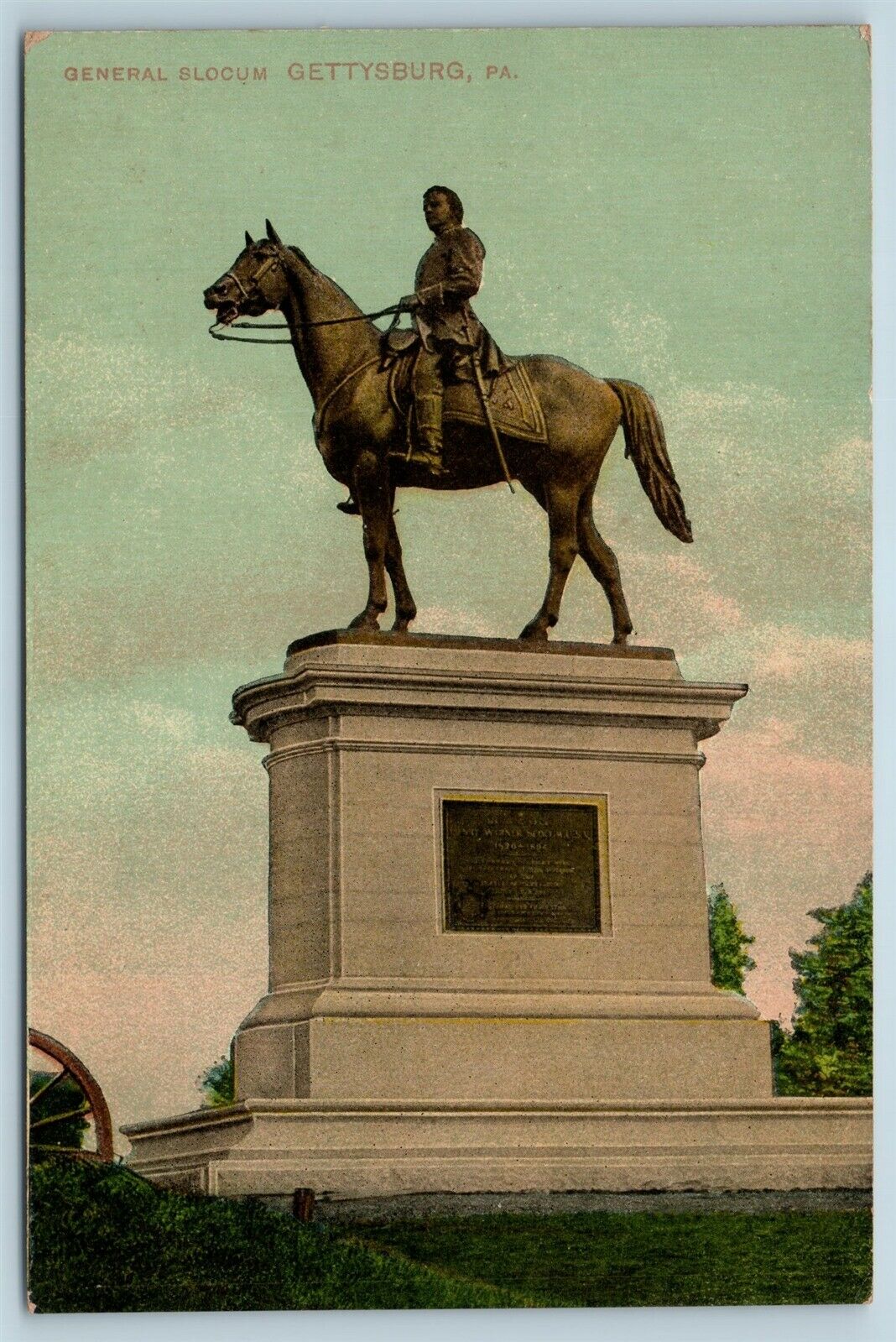

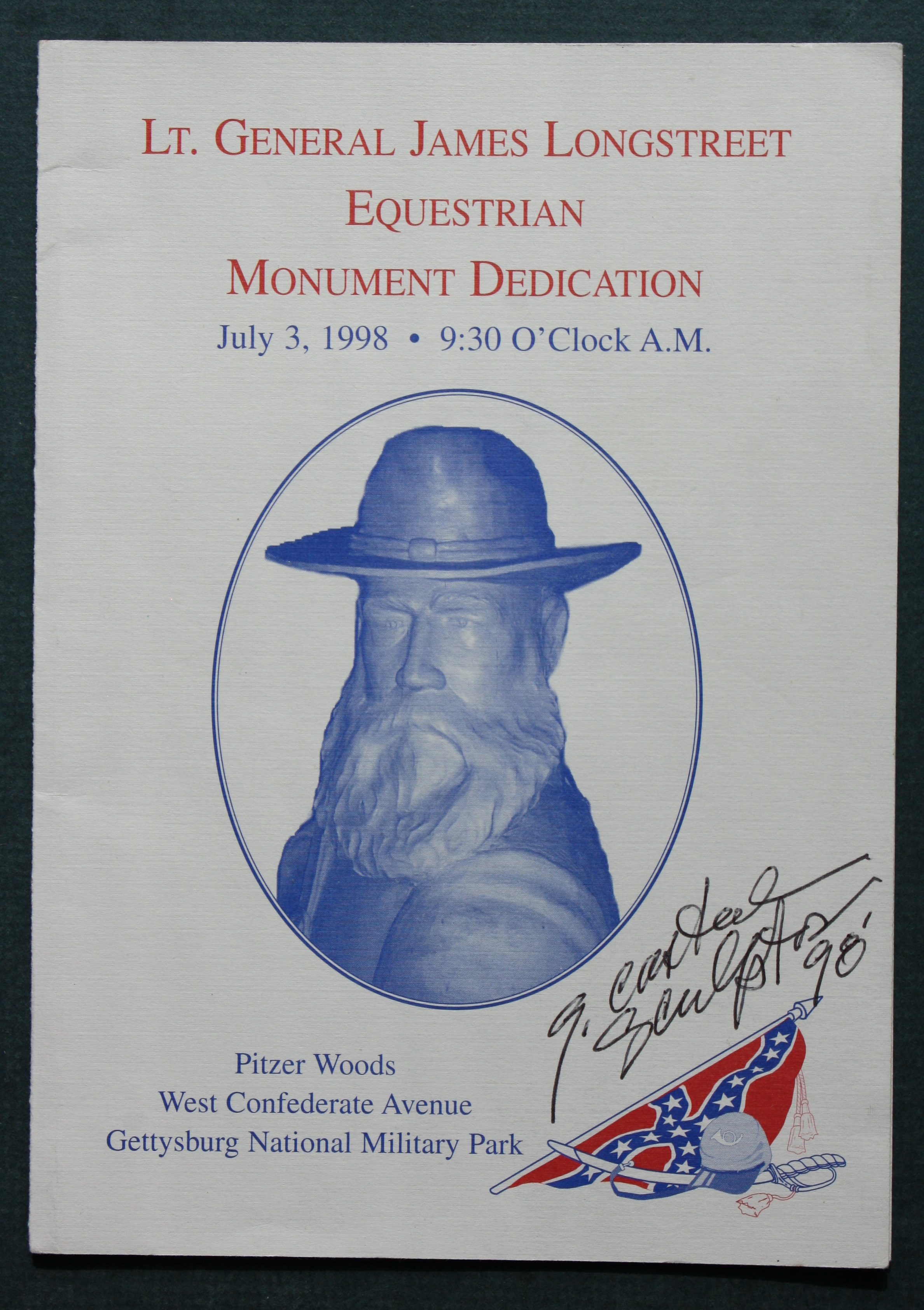

The statues on the field represent Union Generals Meade, Reynolds, Hancock, Howard, Slocum, and Sedgwick, and Confederates, Lee, atop the Virginia Memorial, and James Longstreet. According to the NPS, “Meade and Hancock were the first on June 5, 1896. They were followed by Reynolds, July 1, 1899, Slocum, September 19, 1902, Sedgwick, June 19, 1913, and Howard, November 12, 1932. The Virginia Memorial was dedicated on June 8, 1917. Longstreet did not come along until 1998 and by this time the myth was firmly established.”

The statues on the field represent Union Generals Meade, Reynolds, Hancock, Howard, Slocum, and Sedgwick, and Confederates, Lee, atop the Virginia Memorial, and James Longstreet. According to the NPS, “Meade and Hancock were the first on June 5, 1896. They were followed by Reynolds, July 1, 1899, Slocum, September 19, 1902, Sedgwick, June 19, 1913, and Howard, November 12, 1932. The Virginia Memorial was dedicated on June 8, 1917. Longstreet did not come along until 1998 and by this time the myth was firmly established.” But Hancock’s horse at Gettysburg? No one knows. Likewise, General O.O. Howard’s horse remains nameless (he had at least two shot out from under him and himself was wounded twice in battle) but the sternly pious one-armed General’s nickname of “Uh Oh” survives. So named by soldiers because when the General showed up, one way or another, there was gonna be a fight (he was awarded the Medal of Honor for actions at Gettysburg). Look up at his statue the next time you’re walking the field and you’ll see the empty flap of his right arm (shot off at the Battle of Seven Pines a year earlier) pinned neatly to his coat.

But Hancock’s horse at Gettysburg? No one knows. Likewise, General O.O. Howard’s horse remains nameless (he had at least two shot out from under him and himself was wounded twice in battle) but the sternly pious one-armed General’s nickname of “Uh Oh” survives. So named by soldiers because when the General showed up, one way or another, there was gonna be a fight (he was awarded the Medal of Honor for actions at Gettysburg). Look up at his statue the next time you’re walking the field and you’ll see the empty flap of his right arm (shot off at the Battle of Seven Pines a year earlier) pinned neatly to his coat.

The Opera House hosted the first performance of the inflammatory anti-slavery play “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and its location straddling the North-South boundary caused quite a stir in the days leading up to the Civil War. During the “War of the Rebellion”, the building was used as “Hospital No. 9” and soldiers from both sides of the conflict could often be found lying side-by-side within its walls. In April of 1862, the steamer “H.J. Adams” delivered 200 wounded soldiers to the converted Opera House fresh from the killing fields of Shiloh. In these years before sterilization set the standard of hospital care, a wounded soldier sent to Hospital No. 9, as with any hospital North or South of the Mason-Dixon line, might as well have been handed a death sentence. Many a soldier in Hospital No. 9 would write letters telling friends and family that he was on the mend from a minor battle wound one day, only to die unexpectedly the next day from disease.

The Opera House hosted the first performance of the inflammatory anti-slavery play “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and its location straddling the North-South boundary caused quite a stir in the days leading up to the Civil War. During the “War of the Rebellion”, the building was used as “Hospital No. 9” and soldiers from both sides of the conflict could often be found lying side-by-side within its walls. In April of 1862, the steamer “H.J. Adams” delivered 200 wounded soldiers to the converted Opera House fresh from the killing fields of Shiloh. In these years before sterilization set the standard of hospital care, a wounded soldier sent to Hospital No. 9, as with any hospital North or South of the Mason-Dixon line, might as well have been handed a death sentence. Many a soldier in Hospital No. 9 would write letters telling friends and family that he was on the mend from a minor battle wound one day, only to die unexpectedly the next day from disease. Judy recalls how in 2001, her youngest son David was down in the building’s cellar “fishing” for old bottles in a cistern that he had removed the concrete covering from. “He was laying on his stomach down there alone when he suddenly felt someone tap him on the shoulder” she says, “he looked around expecting to see the source of the poking, but saw that he was still down there alone. Since that time, David does not like to be in the basement by himself.”

Judy recalls how in 2001, her youngest son David was down in the building’s cellar “fishing” for old bottles in a cistern that he had removed the concrete covering from. “He was laying on his stomach down there alone when he suddenly felt someone tap him on the shoulder” she says, “he looked around expecting to see the source of the poking, but saw that he was still down there alone. Since that time, David does not like to be in the basement by himself.” Spirits of a Civil War soldier and a woman in an old fashioned Antebellum Era dress have been seen lounging around the cafe area by a few folks. “Every once in awhile, we’ll get a psychic coming through here telling us that they see the spirits of several Civil War soldiers around the entire building and sense sadness in the basement area.” says Gwinn.

Spirits of a Civil War soldier and a woman in an old fashioned Antebellum Era dress have been seen lounging around the cafe area by a few folks. “Every once in awhile, we’ll get a psychic coming through here telling us that they see the spirits of several Civil War soldiers around the entire building and sense sadness in the basement area.” says Gwinn.

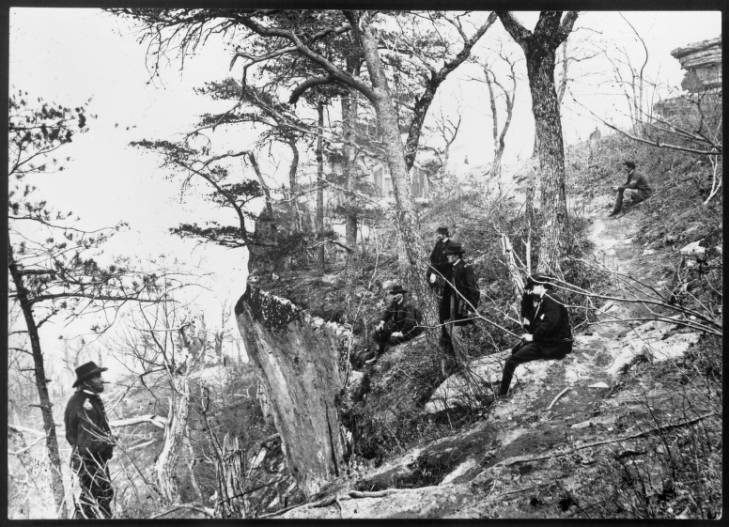

Grant immediately relieved Rosecrans in Chattanooga and replaced him with Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, soon to be known as “The Rock of Chickamauga”. Devising a plan known as the “Cracker Line”, Thomas’s chief engineer, William F. “Baldy” Smith opened a new supply route to Chattanooga, helping to feed the starving men and animals of the Union army. Upon re-provisioning and reinforcing, the morale of Union troops lifted and in late November, they went on the offensive. The Battles for Chattanooga ended with the capture of Lookout Mountain, opening the way for the Union Army to invade Atlanta, Georgia, and the heart of the Confederacy.

Grant immediately relieved Rosecrans in Chattanooga and replaced him with Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, soon to be known as “The Rock of Chickamauga”. Devising a plan known as the “Cracker Line”, Thomas’s chief engineer, William F. “Baldy” Smith opened a new supply route to Chattanooga, helping to feed the starving men and animals of the Union army. Upon re-provisioning and reinforcing, the morale of Union troops lifted and in late November, they went on the offensive. The Battles for Chattanooga ended with the capture of Lookout Mountain, opening the way for the Union Army to invade Atlanta, Georgia, and the heart of the Confederacy.

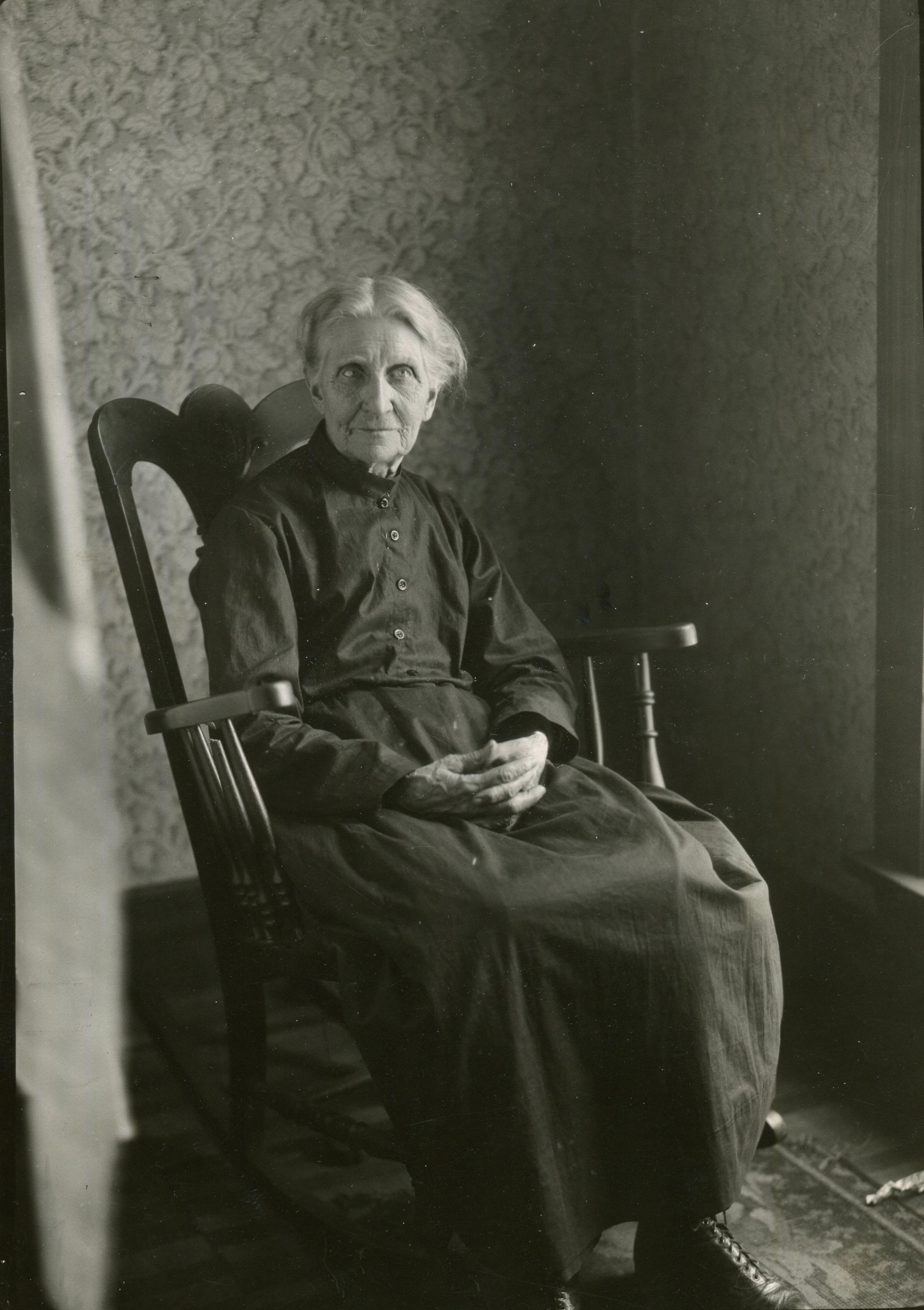

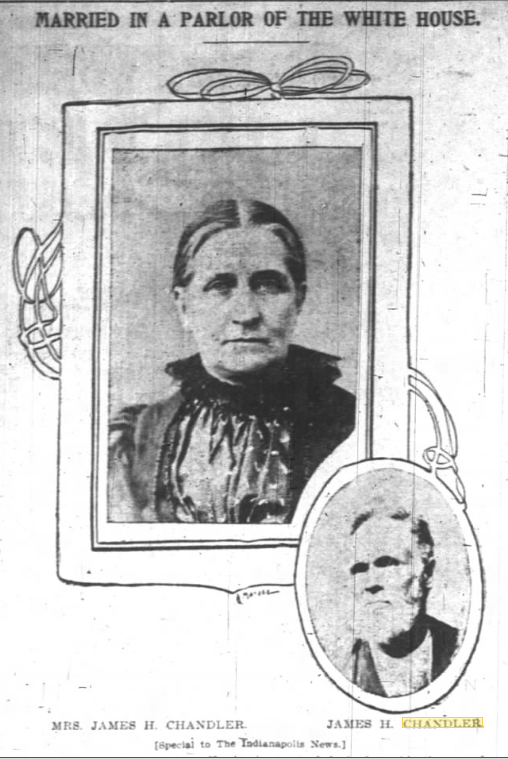

After the minister’s arrived, Lincoln rang a bell and then led the wedding party into a big room, Elizabeth recalled. The president stood alongside the minister and not only did he give the bride away but also acted as the groom’s best man. Elizabeth recalled how he smiled throughout the ceremony. She stated that a Cabinet member stood up with them, but couldn’t recall his name or that of the minister. Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln were the first to shake the newlyweds’ hands. Elizabeth’s most vivid recollection of the nuptials was how scared she was. The president chatted with them awhile and then returned to his office with the unnamed Cabinet member. Elizabeth had worn a plain white cashmere dress for the ceremony. Afterwards, the couple was taken to separate rooms in the White House to change clothes, where Elizabeth changed into a navy blue cashmere dress.

After the minister’s arrived, Lincoln rang a bell and then led the wedding party into a big room, Elizabeth recalled. The president stood alongside the minister and not only did he give the bride away but also acted as the groom’s best man. Elizabeth recalled how he smiled throughout the ceremony. She stated that a Cabinet member stood up with them, but couldn’t recall his name or that of the minister. Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln were the first to shake the newlyweds’ hands. Elizabeth’s most vivid recollection of the nuptials was how scared she was. The president chatted with them awhile and then returned to his office with the unnamed Cabinet member. Elizabeth had worn a plain white cashmere dress for the ceremony. Afterwards, the couple was taken to separate rooms in the White House to change clothes, where Elizabeth changed into a navy blue cashmere dress.