Doc Temple’s century of service is complete, his earthly journey concluded, and he has embarked on the most anticipated trip of his long and happy life, carried on the wings of cardinals to reunite in heaven with his beloved wife Sunderine. Doc’s life, by his own admission, was a dream come true. Born in Ohio’s fields of plenty, Doc was an old soul from the start. With nary a penny in his pocket, at the age of five he carried an old broken pocket watch and chain found abandoned in a farmer’s field as part of his daily attire. He turned that love of timepieces into the preeminent collection of Illinois Watch Company pocket watches known in the state. Governors, senators, congressmen, generals, scholars, and friends today carry an “A. Lincoln” or “Bunn Special” pocket watch with them today, courtesy of Wayne C. Temple. Other creatures received his bounty, too: he fed the cardinals outside his home on Fourth Street Court assiduously and considered every red bird that benefited from his efforts as an earthly manifestation of his wife Sandy, reminding him, over the past three years, that she stood with open arms on the rainbow bridge, awaiting his arrival.

While historians know that Doc was chosen as one of the top 150 graduates of all time from the University of Illinois during its sesquicentennial year of 2017, not many realize that Doc was also an accomplished poet, living his life with poetry in his soul. He sprouted as a poor Ohio farm boy with an unquenchable thirst for history, education, and life, with his first love the English language. He put that adoration for the printed word to good use in elocution contests and essays that were the first signs of his innate talent. From those humble beginnings, Doc served his country in Europe, slept on castle floors, befriended a General named Eisenhower who would soon become President, and drank the wine of emperors gifted to him by grateful war-torn communities that he literally brought back to life with his engineering skills. Of course, Doc shared Napoleon’s wine with his battle buddies. Doc’s flame burned brighter than any other historian in Illinois’s history, and the prowess of his Lincoln scholarship was unchallenged for half a century. He spent a career burning holes in the pages of others’ older history by his meticulous research, yet Doc’s flame always warmed, never burned those around him. He was quick to share information with all who sought his advice. Whether you were a budding scholar, land surveyor, dentist (yes, Doc was an honorary dentist), lawyer, politician, historical enthusiast, tourist, or student, Doc always had time to lend a hand in the most generous fashion. He never concerned himself about attribution or credit; his mantra was always “Get the information out there.” Some of it was new information, too: Each year he wrote Sandy an original poem, in rhyme, for her birthday or anniversary.

Although Doc stood front and center for every important Illinois event, commemoration, or big reveal for the past seven decades, you’d never know it by his demeanor. If he wasn’t on the dais, he was in the front row. During his career in the Archives, he was just as excited to meet Hoss Cartwright’s school teacher as he was to meet the Vice-President of the United States. Doc’s presence will be sorely missed, his record of 54 years, 7 months service to the state of Illinois may never be surpassed, and his space in the Lincoln field will remain unfilled. His passing came with typical military precision, bisecting the clock at precisely 1230 hours, the hands on the clock in an upswing, moving up, not down, on the final day of March. Doc’s transition occurred exactly at the conclusion of his life’s seasonal winter to burst forth to the heavenly spring we all hope awaits our final journey. Doc would remind us all, with a wink and a smile, that he also waited until after the St. Louis Cardinals home opener had arrived.

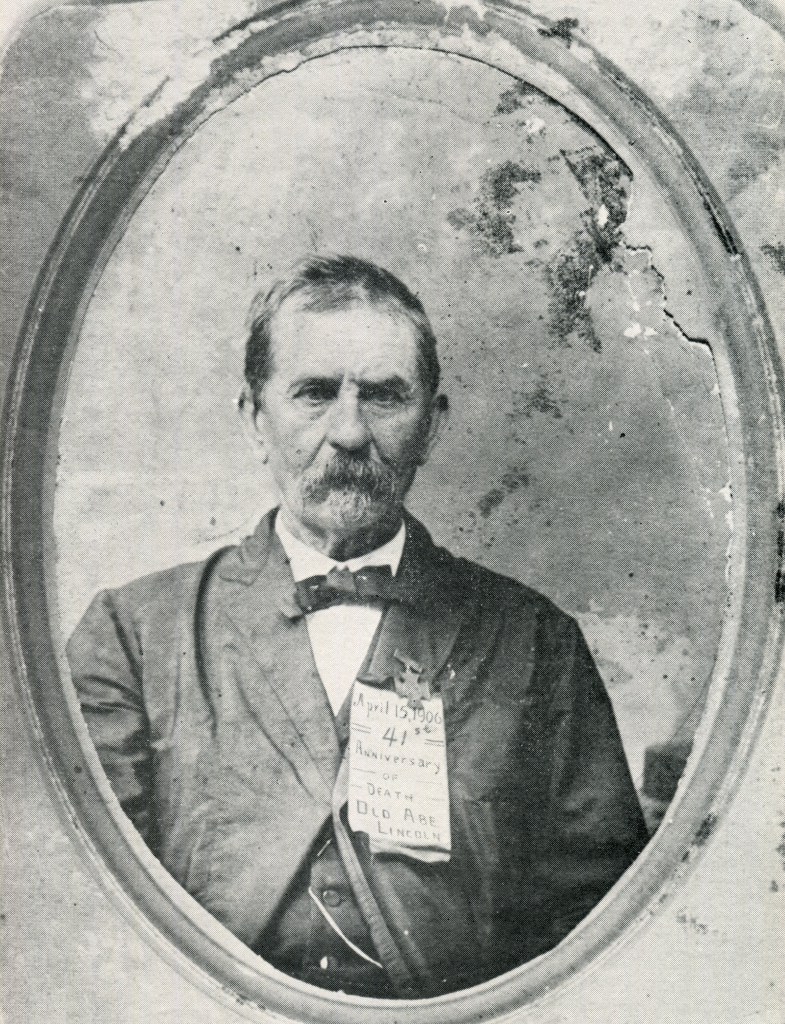

Wayne Calhoun Temple, the dean of Lincoln studies and for half a century the mainstay of the Illinois State Archives, died peacefully on March 31, 2025, at a care facility in Chatham, Illinois. Devoted friends Teena Groves and Sharon Miller were present Wayne Calhoun Temple, the dean of Lincoln studies and for half a century the mainstay of the Illinois State Archives, died peacefully on March 31, 2025, at a care facility in Chatham, Illinois. Devoted friends Teena Groves and Sharon Miller were present and biographer Alan E. Hunter was on the phone with them at the time of his passing. He was predeceased by his beloved wife Sandy (2022), and by his parents Howard (1971) and Ruby (1978) Temple, of Richwood, Ohio.. He was predeceased by his beloved wife Sandy (2022), and by his parents Howard (1972) and Ruby (1977) Temple, of Richwood, Ohio.

Temple, known to all for 60 years as “Doc,” was born on a small family farm two miles east of Richwood (about 40 miles north of Columbus), on Feb. 5, 1924. He liked to note that he shared a birthday with Lincoln’s mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln. He was an only child. From his mother, a teacher, he learned literature, history, and music; from his father, he learned how to ride, how to shoot, how to plant and reap. An oft-repeated story is how at age 9 years he encouraged his parents to go see the fair in Chicago in 1933 as they wished. He persuaded them that he’d be fine and he was – he had the horse, the cart, and the rifle.

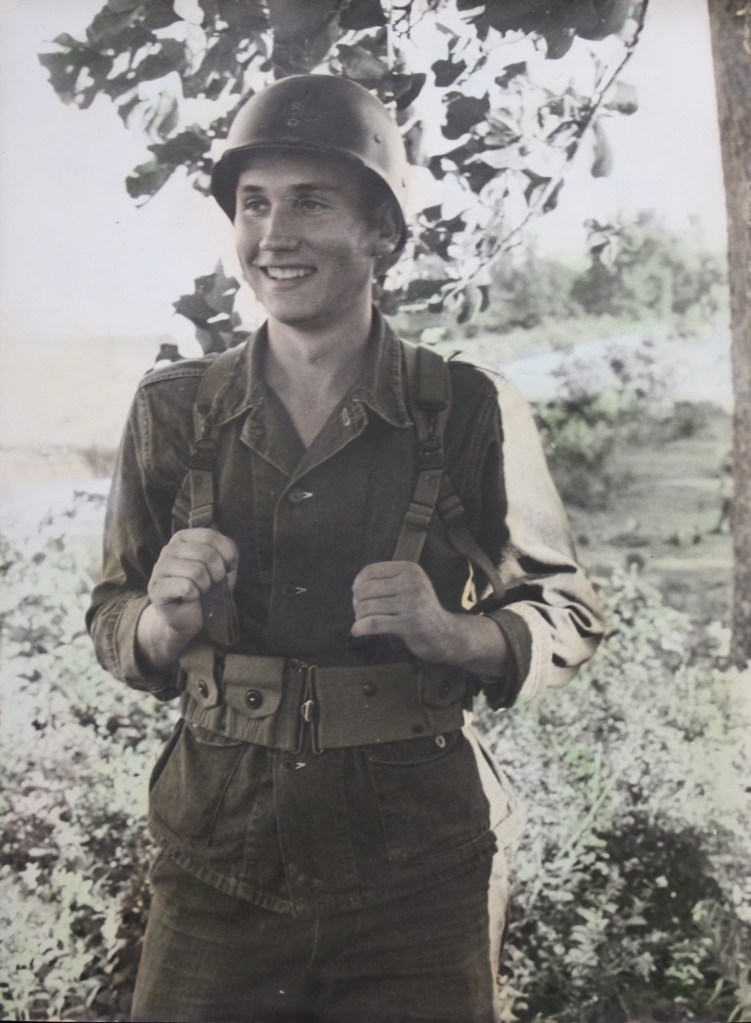

After a one-room-schoolhouse start, in high school he was valedictorian and ran on a championship 1,500-yard 4-man relay team. He played clarinet in a traveling band of adult men. In 1941, he entered Ohio State University on a football scholarship, intending to study chemistry. He was soon drafted into the Army Air Corps and sent to Urbana, Illinois, for training as an engineer. He and his mates were sent to North Carolina for special training; then to Kansas for ordnance production.

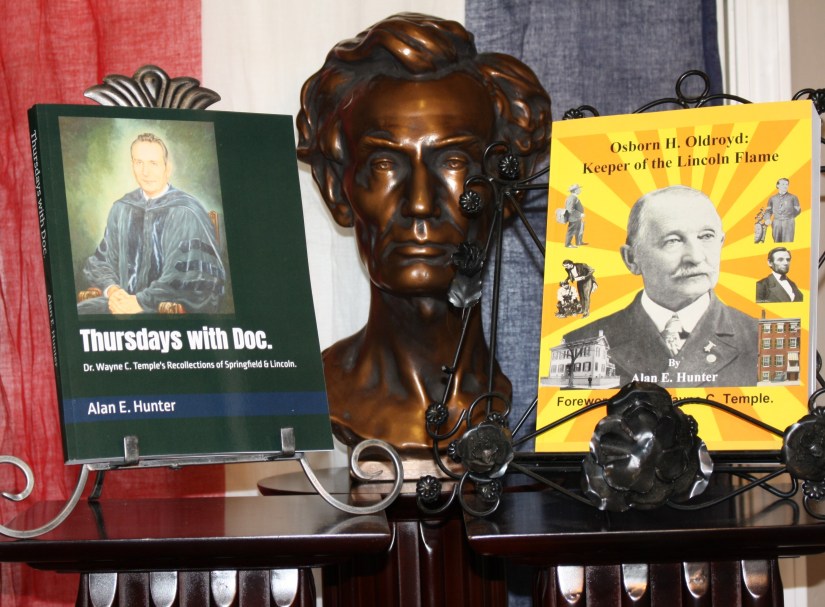

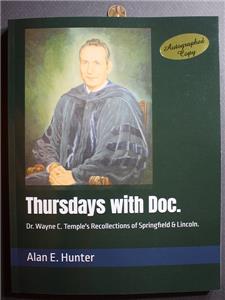

He spent 1945-46 in Europe, and at age 21 as a Tec 5 in the Signal Corps (grade of a sergeant), he helped install new airfields and radio communications, some of it personally for General-in-Chief Eisenhower. Many more details are found in Alan E. Hunter’s remarkable oral-history-as-life-study, Thursdays with Doc (2025), copies of which Temple signed in his last months of life.

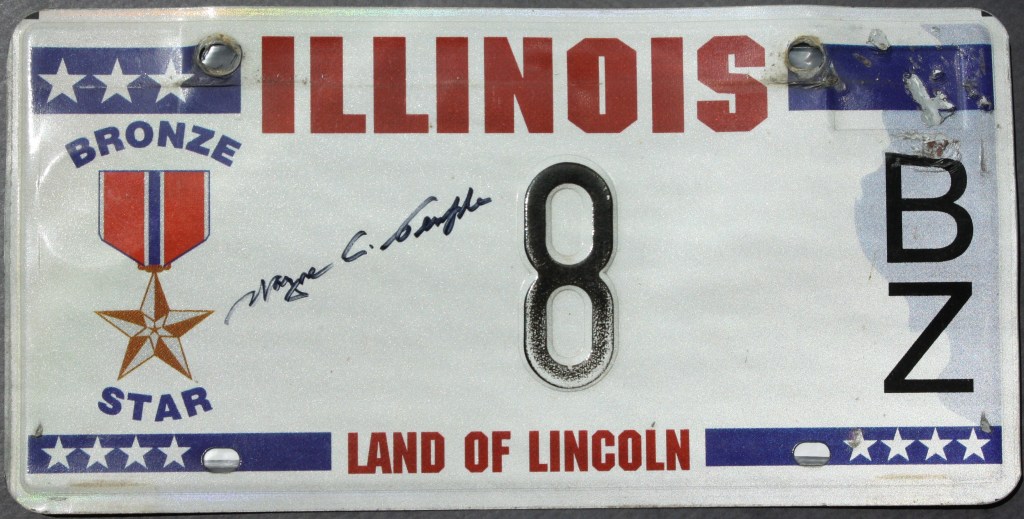

He was awarded the Bronze Star for his one-man battle with a Luftwaffe pilot who strafed their camp on the Franco-German border in the last weeks of the war. While others dove for the ditch, Doc used his favorite weapon, the Thompson submachine gun, to fire upward at the plane. “Did you hit him?” Doc was later asked. “I don’t know, but he didn’t come back.”

After the war he returned to the U. of Illinois, earning a war-interrupted B.A. in History and English. Here, he was discovered by Prof. James G. Randall, the first academic historian of Lincoln, and became his graduate student and research assistant until “Jim’s” death in 1953. Temple helped him write vol. 3 of the tetralogy Lincoln the President (1945-55) and rough out vol. 4 although a more senior scholar got credit as co-author. Temple also helped Ruth Randall with her popular and “junior” histories about the Lincolns and women of the Civil War era, and corresponded with her until her death in 1971.

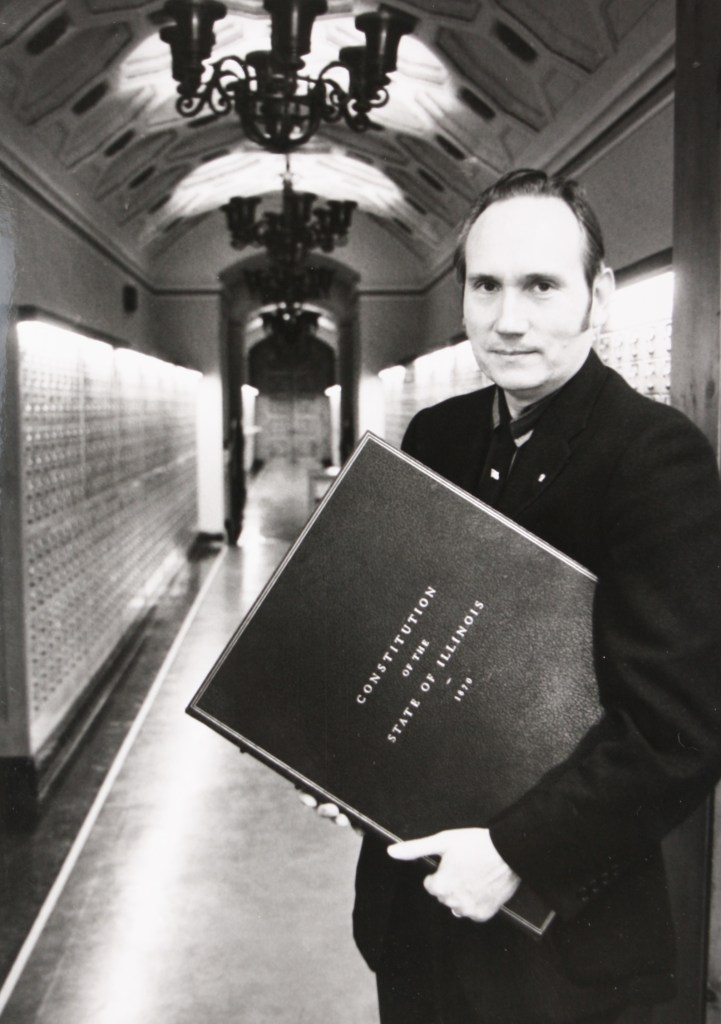

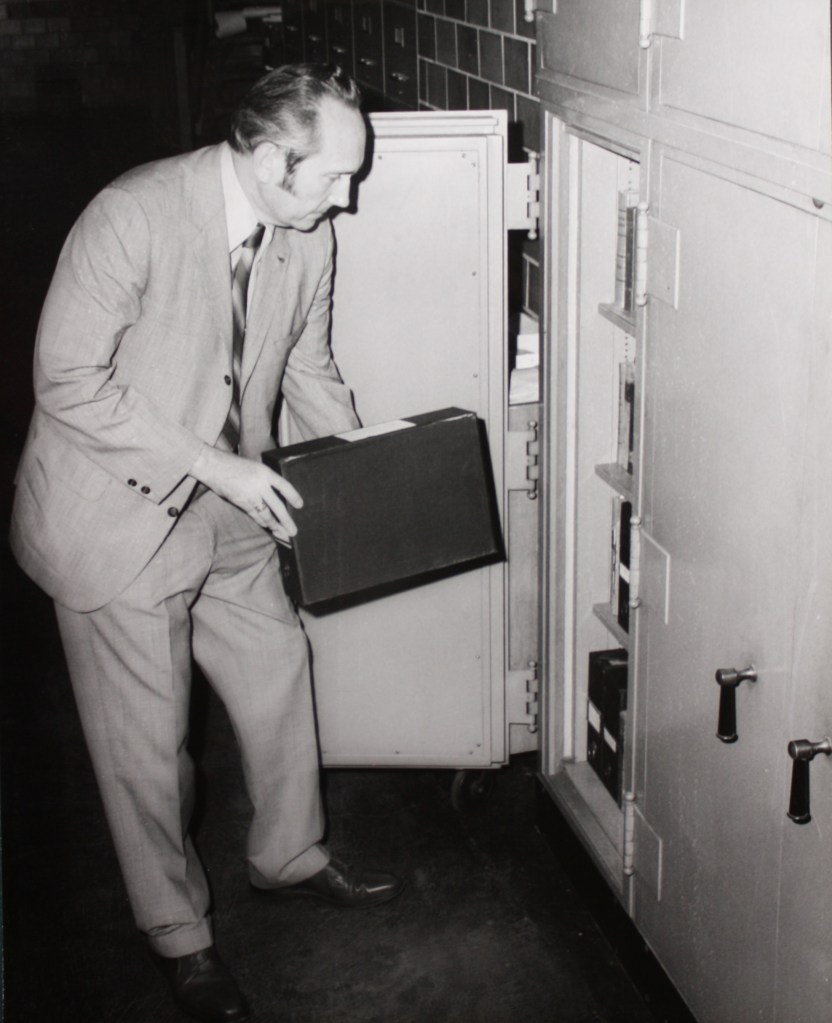

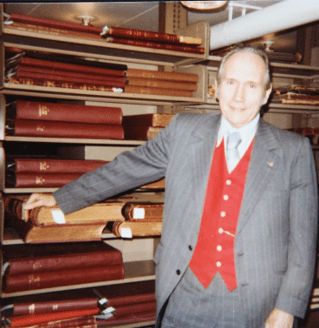

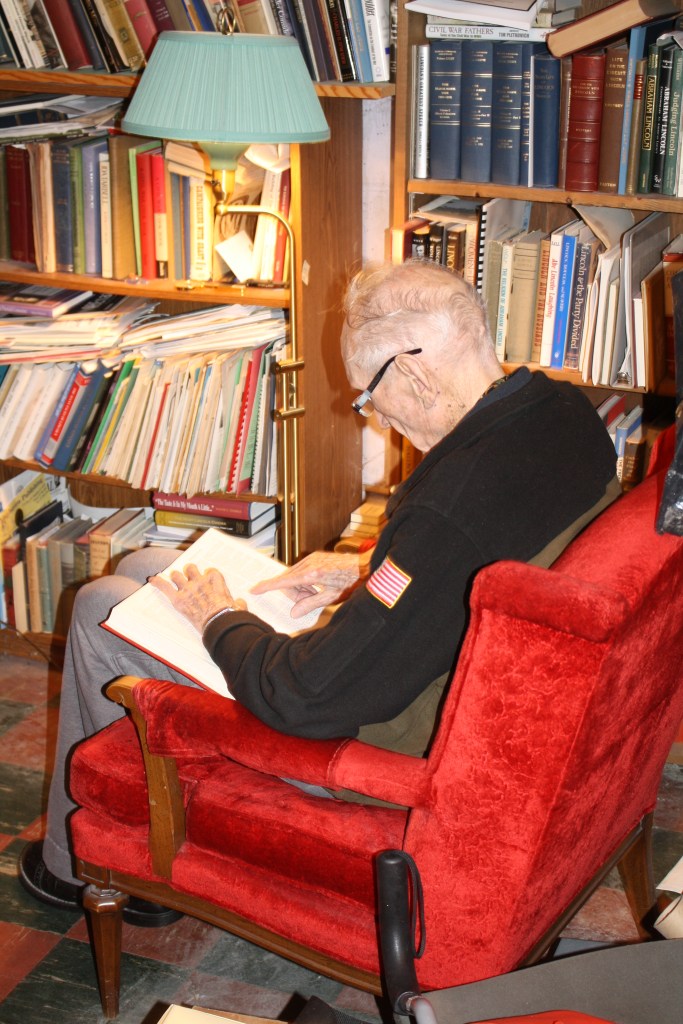

His first book was commissioned and remunerated handsomely by Thorne Deuel of the Illinois State Museum, on Indian Villages of the Illinois Country (1958), still considered a model of research and analysis. From there Temple took his wife Lois McDonald Temple to Lincoln Memorial University, Harrogate, Tennessee, to head up the history department. They remained in touch for decades with some of the young women who assisted in the department. He edited The Lincoln Herald there, making it the best periodical in the field, and remained as editor till the mid-1970s, long after the Illinois State Archives in 1964 brought him on staff. For decades before his retirement there in 2016 he was permanent Chief Deputy Director. (Lois died in 1978; Doc and Sandy met and married in 1979.) He no longer taught classrooms, helping instead an average of 150 people per month for a half-century who called, wrote, or walked in with questions at the Archives – in addition to speaking and writing publicly more than most fulltime professors. Land surveying, one of Temple’s many skills, proved invaluable for the dozen survey questions a month on that topic, alongside tracing the course of legislative bills old or new, gubernatorial proclamations, or judicial rulings. He mastered the use of old registers, microfilm, and the typewriter, but never took to computers. Nine secretaries of State, of both parties, kept Temple on, recognizing his value to the state and to the public; tech-savvy assistants like his friend Teena Groves made the office efficient, complementing Doc’s top-notch research work.

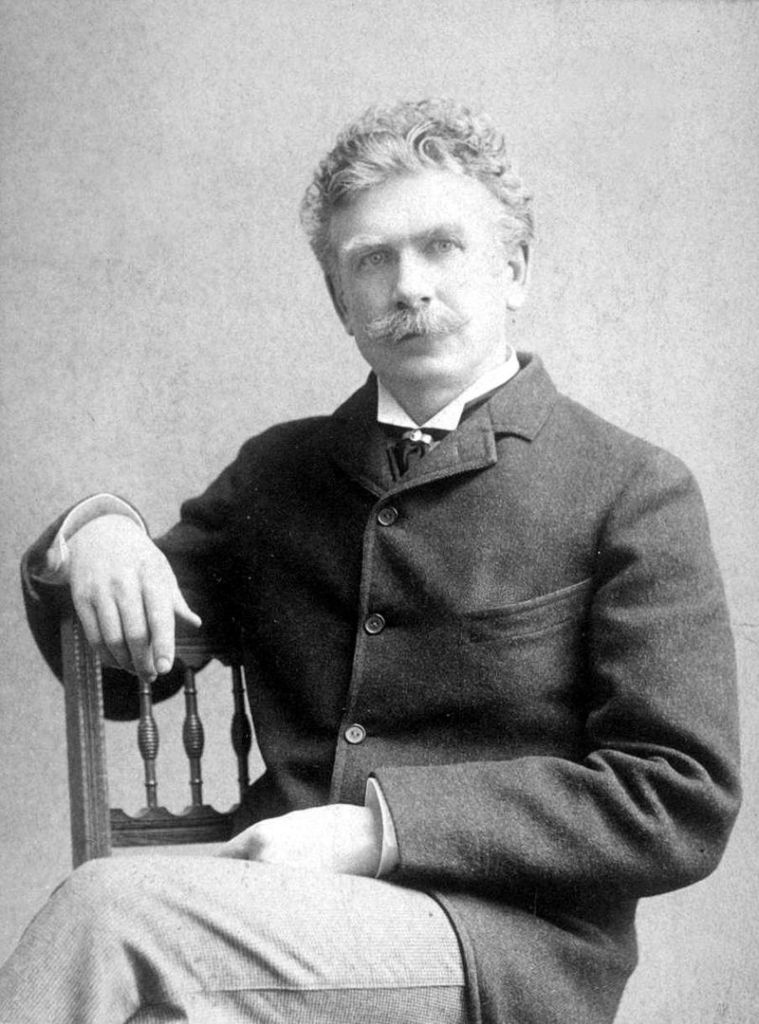

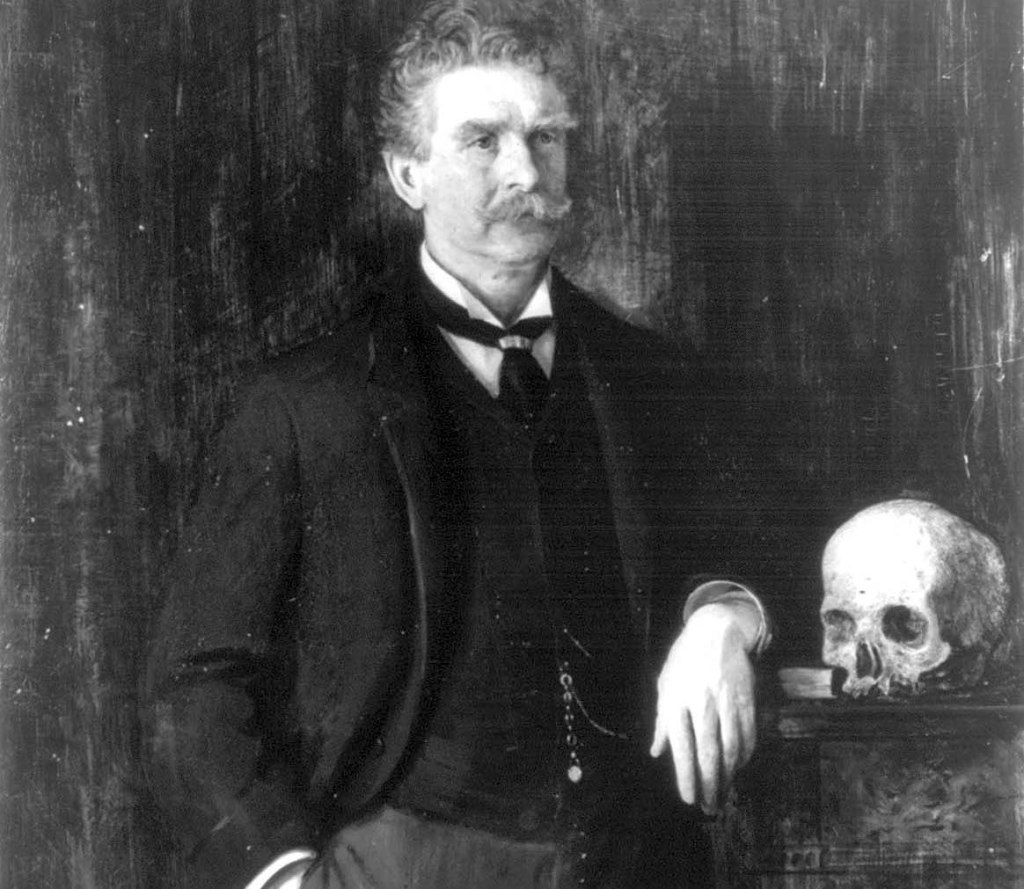

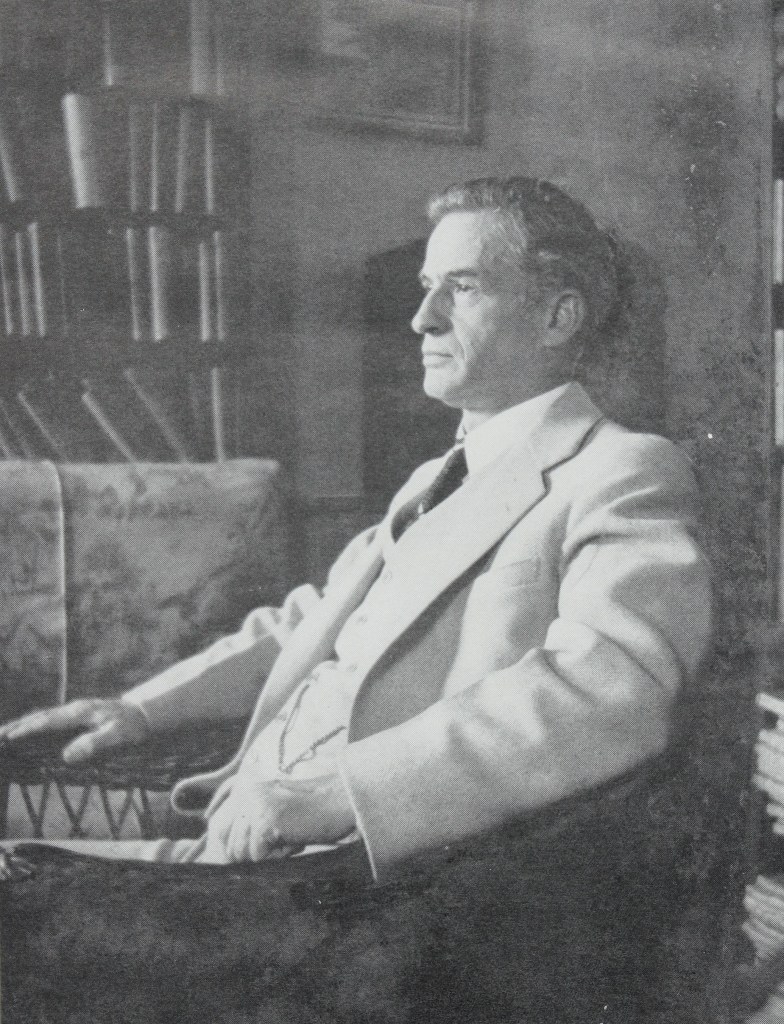

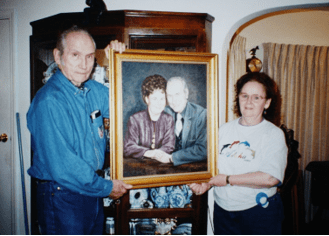

Dayton Ohio artist Lloyd Ostendorf.

At the popular level he engaged artist Lloyd Ostendorf to illustrate the Lincoln Herald with Temple’s precise historical notes on people’s heights, demeanor, clothing, armaments, supported by background architecture and horsetack, for the best historic illustrations of any American’s circle of friends and colleagues. These scenes were set in dozens of Illinois cities and towns around the legal or political circuit, plus Lincoln’s White House years. Supporting local-history projects with Phil Wagner, John Eden of Athens, the Masonic Lodge, and towns themselves, Temple also helped re-create dramatic moments of the past. The Lincoln Academy of Illinois made him a Regent in the 1960s with a nomination by a governor from each party, and he was elected a Laureate in 2009, the highest honor in the State’s gift. Helping in 1969 to reactivate the 114th Illinois Volunteer Infantry of the Civil War era, he rose in its ranks from Lt. Col. to full General, presiding at dozens of ceremonies. Nationally he was a member of the U.S. Civil War Centennial Commission (1960-1965); was invited to recite the Gettysburg Address on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial with President Nixon and other officials present in 1971, then to speak to the Senate about the Lincoln boys’ Scottish-born tutor Alexander Williamson; and in 1988 was present for the commissioning of the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln. Privately and at work he was asked to weigh in on the authenticity of dozens of Lincoln documents owned by private collectors.

Temple’s published works remain the testament to his great energies and skill. With wife Sunderine, a.k.a. Sandy, who for 40 years was a head docent at the Old State Capitol, he wrote Illinois’ Fifth Capitol: The House that Lincoln Built and Caused to Be Rebuilt (1837-1865) (1988), the standard work on its initiation, contracts, costs, furnishing, refurbishing, and historic moments such as Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech in 1858. In like vein he wrote up the Lincoln Home, in By Square and Compasses (1984; updated 2002). For shorter works he found or recovered the stories of people high and low, including Mariah Vance, the Lincolns’ African-American laundress; Barbara Dinkel, a German-born widow down the block; two Portuguese immigrants nearby; Robert Lincoln’s ability to play the piano; and father Abraham’s formal commission as an Illinois militia officer after the Black Hawk War of 1832, which he maintained throughout his life by attending the annual muster. C. C. Brown, namesake of the oldest continuous business in Illinois – the law firm Brown, Hay, & Stephens (est. 1828) — offered some thoughts on working with Lincoln which Temple found and turned into a booklet in 1963. Probably his most enduring book will be Abraham Lincoln: From Skeptic to Prophet (1995), on the religious views, which Temple called not merely a religious study but “really a biography of the Lincoln family.” Lincoln’s many connections to Pike County introduced a book about the area’s Civil War record; his trip through the Great Lakes in 1849 gave rise to a booklet about the Illinois & Michigan Canal and Lincoln’s patented invention. Some of the best of Temple’s 500 to 600 articles are being collected into a book edited by Steven Rogstad.

Personally Temple was highly generous, helping Sandy’s distant family when in need, serving as an Elder and teacher at the First Presbyterian Church, and endowing the UI Urbana History Dept. with funds from his estate. On behalf of wife Lois’s nephew, Temple headed a Boy Scout troop in town. Doc gave his father’s canful of ancient Indian artifacts dug from the Ohio farm to the public library in Richwood, Ohio, as one of his last acts, though he could have sold them for many thousands of dollars. When Temple learned that his barber, a father of five, could not afford to send his bright youngest son to college, Temple spoke to Congressman Paul Findley, who got the young man appointed to the Academy at West Point, and a successful military career was launched. Temple’s collection of 3,000 books is bound for UI Springfield’s Lincoln Studies Center, while his fine collection of artworks as well as personal papers will go to the Presidential Library and Museum.

In the opinion of the person who succeeds Temple as the dean of Lincoln historians, Prof. Michael Burlingame of UI Springfield, Doc “displayed an uncanny ability to unearth new information about Lincoln through painstaking research … For over eight decades, he tenaciously filled many niches in the Lincoln story.” His neighbor of 43 years, Sharon Miller, said, “Doc was simply a wonderful man. But he missed Sandy too much to keep going.”

A memorial service will be held on Thursday, April 10th, at 10:00 a.m. at Staab Funeral Home, S. 5th St. in Springfield. Burial will take place at 1:00 p.m. at Camp Butler National Cemetery, next to Sandy temple’s gravesite. A reception at the St. Paul’s #500 A.F. & A.M. Lodge on Rickard Drive will follow.