Original publish date June 19, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/06/19/nazi-ideology-on-the-eastside-a-contnuance/

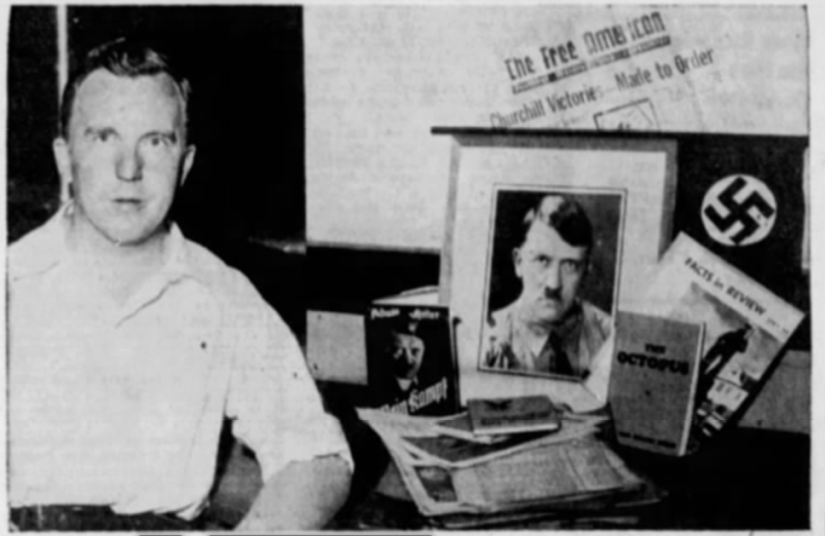

Last March, I wrote a two-part article on Eastsider Charles Soltau, the “Nazi at Arsenal Tech”. This Saturday (June 21st) at noon, I will revisit those articles on Nelson Price’s “Hoosier History Live” radio show WICR 88.7 FM. Nelson, a longtime friend of Irvington, has a personal connection to that story, which he will share for the first time ever during that broadcast. As it happens, weeks after that article appeared, quite by accident, I ran across a few documents that spoke directly to that time in Indianapolis history.

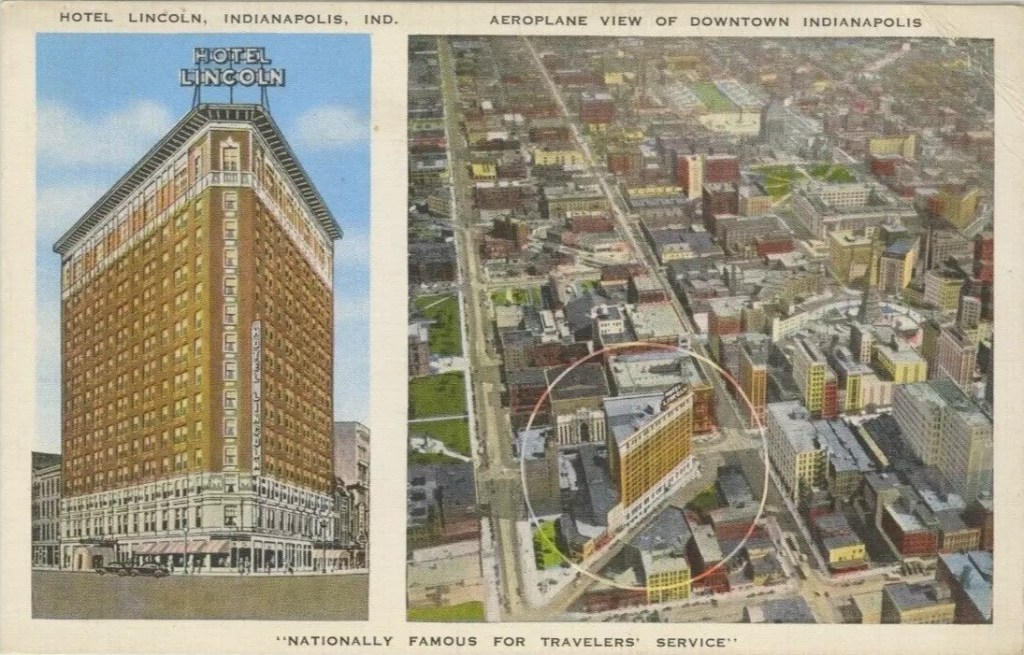

While perusing a few boxes of vintage paper at a roadside antiques market, I found a pair of cards from February 1938, advertising one of the first 35 mm camera photo exhibitions in Indianapolis at the Hotel Lincoln. The Hotel Lincoln, built in 1918, was a triangular flat-iron building located on the corner of West Washington St. and Kentucky Ave. The hotel was named in honor of Abraham Lincoln, who made a speech from the balcony of the Bates House across the street in 1861. Afterwards, that block became known as “Lincoln Square.” The Hotel displayed a bust of Abraham Lincoln on a marble column in its lobby for decades. The Lincoln was a popular convention center and was once the tallest flat-iron building in the city. The Lincoln was the site of the arrest of musician Ray Charles (a subject covered in depth in one of my past columns). It also served as the headquarters for Robert Kennedy and his campaign staff, who leased the entire eleventh floor of the hotel during the 1968 Indiana primary. The Lincoln was intentionally imploded in April of 1973.

It was the Hotel Lincoln’s history that originally piqued my interest. The front of each card read, “You are invited to attend the Fourth International Leica Exhibit on display in the Hotel Lincoln, Parlor A, Mezzanine Floor, Indianapolis, Ind., from February 23 to 26 [1938], inclusive. Hours: 11 A.M. to 9 P.M. (on February 26, the exhibit will close at 5 P.M.) More than 200 outstanding Leica pictures will be on display, representing the use of the camera in various fields…Candid, Amateur, Commercial, Press and Scientific Photography. Do not fail to view this show which represents the progress in miniature camera photography throughout the year. Illustrated Leica Demonstration will be given at the American United Life Insurance Co., Auditorium, Indianapolis, February 24, 8:30 P.M. by Mrs. Anton F. Baumann. ADMISSION FREE. E. Leitz, Inc. New York, N.Y.” Research reveals that the winner of the contest was W.R. Henkel, who resided at 2936 E. Washington Street. Henkel received the Oscar Barnak Medal, named for the inventor of the Leica camera.

The Leica was the first practical 35 mm camera designed specifically to use standard 35 mm film. The first 35 mm film Leica prototypes were built by Oskar Barnack at Ernst Leitz Optische Werke, Wetzlar, in 1913. Some sources say the original Leica was intended as a compact camera for landscape photography, particularly during mountain hikes, but other sources indicate the camera was intended for test exposures with 35mm motion picture film. Leica was noteworthy for its progressive labor policies which encouraged the retention of skilled workers, many of whom were Jewish. Ernst Leitz II, who began managing the company in 1920, responded to the election of Hitler in 1933 by helping Jews to leave Germany, by “assigning” hundreds (many of whom were not actual employees) to overseas sales offices where they were helped to find jobs. The effort intensified after Kristallnacht in 1938, until the borders were closed in September 1939. The extent of what came to be known as the “Leica Freedom Train” only became public after his death, well after the war.

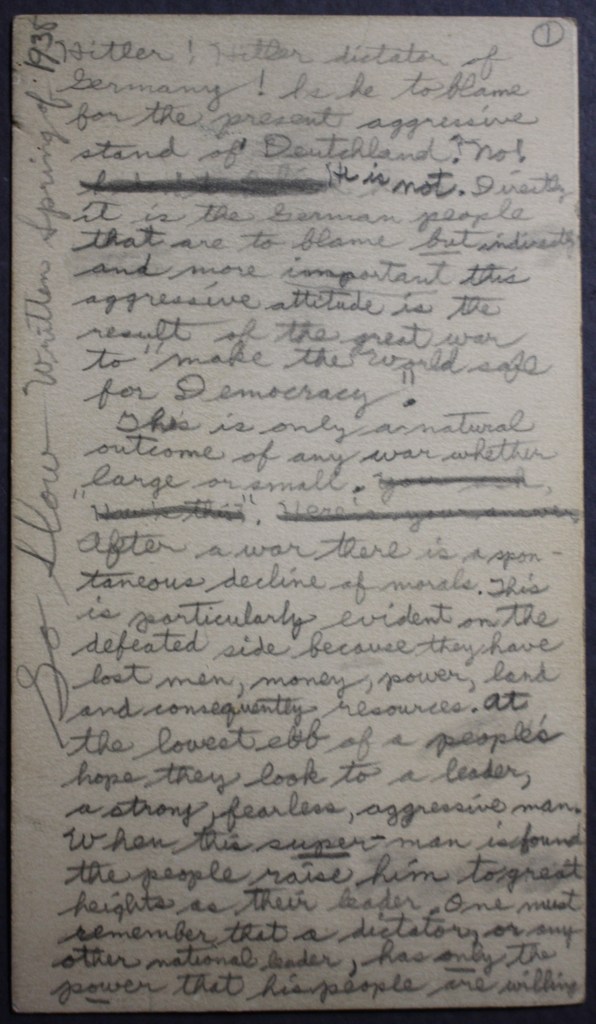

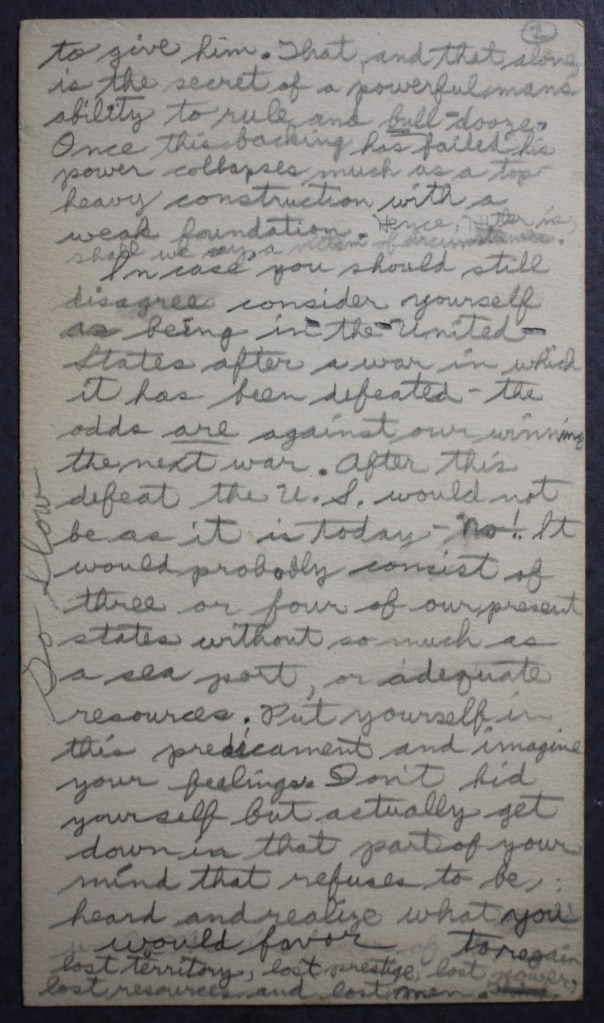

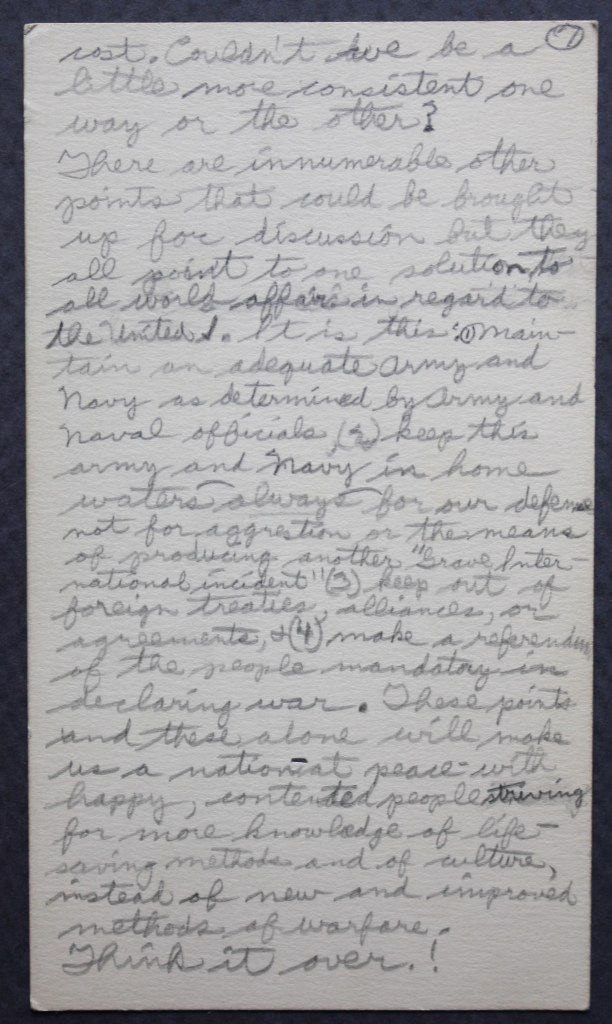

While my interest was drawn to the printed text, it was the handwritten pencil notations on the back of the cards that sparked that purchase. The cards contained a contemporary essay about the political atmosphere in the Circle City less than a month after the Soltau family’s Nazi incident. Written in pencil, the cards, numbered 1 and 2, read: “Hitler! Hitler Dictator of Germany! Is he to blame for the present aggressive stand of Deutchland? No! He is not. Directly, it is the German people that are to blame but additionally and more importantly, this aggressive attitude is the result of the great war to “make the world safe for Democracy!!” This is only a natural outcome of any war, whether large or small. After a war there is a spontaneous decline of morals. This is particularly evident on the defeated side because they have lost men, money, power, land, and consequently, resources. At the lowest ebb of a people’s hope they look to a leader, a strong, fearless, aggressive man. When this superman is found, the people raise him to great heights as their leader. One must remember that a dictator, or any other national leader, has only the power that his people are willing to give him. That, and that alone, is the secret of a powerful man’s ability to rule and bulldoze. Once the backing has failed, his power collapses much as a top-heavy construction with a weak foundation. Hence, Hitler is, shall we say, a victim of circumstance. In case you should still disagree, consider yourself as being in the United States after a war in which it has been defeated; the odds are against ever winning the next war. After this defeat the U.S. would not be as it is today. It would probably consist of three or four of our present states without so much as a seaport or adequate resources. Put yourself in this predicament and imagine your feelings. Don’t kid yourself but actually get down in that part of your mind that refuses to be heard and realize what you would favor to regain lost territory, lost prestige, lost power, lost resources, and lost men.”

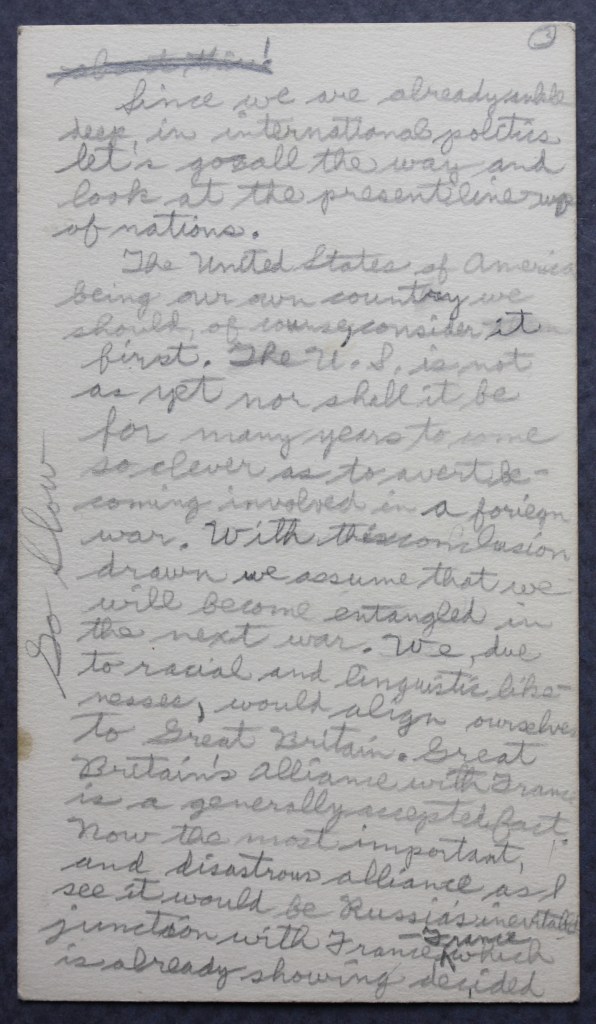

The next week, I revisited that roadside market. Lo and behold, the same dealer was there, and he brought more boxes of paper. I found two more of those cards, numbered 3 & 7, with more of that essay featured on the reverse. “Since we are already ankle deep in international politics, let’s go all the way and look at the present lineup of nations. The United States of America, being our own country, we should, of course, consider it first. The U.S. is not as yet, nor shall it be for many years to come so clever as to ever become involved in a foreign war. With this conclusion drawn, we assume that we will become entangled in the next war. We, due to racial and linguistic likenesses, would align ourselves to Great Britain. Great Britain’s alliance with France ia a generally accepted fact . Now the most important and, disastrous as I see it, would be Russia’s inevitable junction with France, which is already showing decided…Couldn’t we be a little more consistent one way or the other?”

“There are innumerable other points that could be brought up for discussion, but they all point to one solution to all world affairs in regard to the United States. (1) It is this: maintain an adequate army and navy as determined by Army and Navy officials. (2) Keep this army and navy in home waters always for our defense and not aggression or the means of producing another “Grave international incident.” (3) Keep out of foreign treaties, alliances, or agreements. (4) Make a referendum of the people mandatory in declaring war. These points, and these alone, will make us a nation at peace with happy, interested people striving for more knowledge of lifesaving methods and of culture, instead of new and improved methods of warfare. Think it over!”

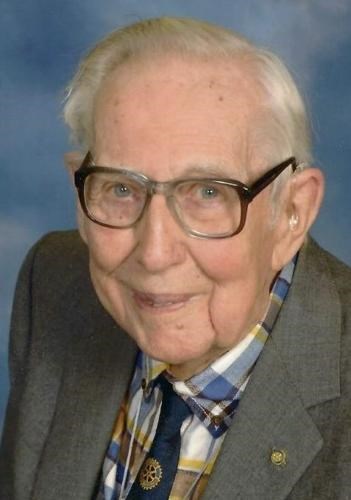

All four of these cards were authored (and signed) by Bob Shoemaker, Jr. of Anderson, IN. Robert W. Shoemaker, Jr. (1921-2022) Bob was born in New Philadelphia, Ohio, the only child of Robert W. Shoemaker, Sr. (1898-1968) and Irene English Shoemaker (1900-1988). The family moved to Anderson in 1935. Shortly after settling in Indiana, Bob became a Boy Scout. While attending the 1937 National Boy Scout Jamboree in Washington DC, Bob received his Eagle Scout award. It is likely that the seeds of this essay were planted when he sailed to Europe to participate in the 1937 World Jamboree in the Netherlands. Here, young Bobby Shoemaker witnessed the changes taking place in Hitler’s Germany firsthand. After graduating from Anderson High School in 1939, Bob enrolled in Harvard College and was on course to graduate with the Class of 1943 when the war came calling. Among Bob’s hobbies and interests were amateur radio, reading, history, and photography. Through slides, home movies, and videos, Bob compiled a remarkable visual history of his life and the life of his family from the 1920s to the current century. His many slides and movies taken during the 1937 Jamboree trips provide a fascinating glimpse of life in Washington DC, and Europe before the tragic onset of World War II. It was that love of photography that drew Bob to that Leica Exhibit at the Hotel Lincoln in Indianapolis back in 1938.

Bob was commissioned as an ensign in the U.S. Naval Reserve in 1942 and attended officers’ training programs in the Bronx, NY, and Washington, D.C, before being assigned to the Naval Mine Warfare Test Station at Solomons Island, MD, where he served as Naval personnel officer. After requesting a shipboard assignment, Bob was transferred to the Pacific for duty aboard the escort aircraft carrier U.S.S. Corregidor (CVE-58) as Lieutenant Junior Grade and Signal Officer until the ship’s decommissioning after the war in 1946. After World War II, Bob earned two graduate degrees from Harvard: an MBA and a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Government in 1947. Upon his return to Anderson in 1947, Bob remained active in the U.S. Naval Reserve Division 9-31. In 1949, Bob and his parents purchased Short Printing, Inc., then located on 20th Street near Fairview Street in Anderson. He successfully operated the business as President for almost five decades, which included building a larger one on Madison Avenue in 1961 and changing the name to Business Printing, Inc. He retired and sold the business in 2000. Bob was a Scoutmaster and Skipper of a Sea Scout ship in Anderson. He also held a variety of district and council leadership positions in Scouting for many years.

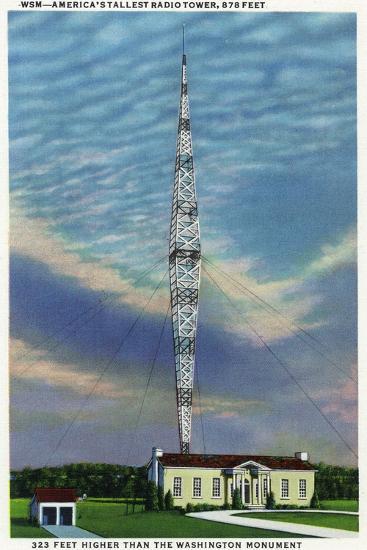

In 1946, Bob obtained his amateur radio license, and in 1952, he was asked to organize amateur radio communications for the Madison County Civil Defense, which led to his appointment as County Civil Defense Director, a position he held for 12 years. This period witnessed rising tensions with the Soviet Union and the threat of nuclear attacks, including the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. As CD Director, Bob gave many educational slide presentations regarding proper preparations in the face of nuclear threats, oversaw the selection and stocking of emergency fallout shelters throughout the county, and helped organize the conversion of the old Lindbergh School north of town into a CD emergency command headquarters. His slide show included photos taken in his capacity as an official observer at the Yucca Flats, Nevada, nuclear test in 1955. Later, Bob was invited by NASA to Cape Canaveral to observe the launch of Apollo 8, which carried astronauts into orbit around the moon for the first time, and the Apollo 15 moon mission launch. As a seven-decade member and officer of the Rotary Club, Bob secured NASA astronaut Al Worden, command module pilot for Apollo 15 and one of 24 people to have flown to the Moon, as a special speaker for the Madison County Rotary Club in 1971.

When Bob Anderson Jr.’s life is measured against that of his “peer,” Arsenal Tech grad Charles Soltau, it is easy to see that while both shared the same isolationist mentality as young men, one chose to follow that Nazi ideology of Adolf Hitler and the other followed that of Uncle Sam. Soltau faded into the obscurity that Gnaw Bone, Indiana, maintains to this day. Anderson became a public-spirited pillar of Madison County society whose shadow is still cast in that community — proving that idealogy comes and goes with the flow of generations. What often sounds like an attractive idea can easily morph into an unexpectedly bad outcome. Mark Twain is often quoted as having said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes,” and, if so, it applies today.

I will be talking about this series of articles with Nelson Price on his radio show “Hoosier History Live” this Saturday June 21, 2025 noon to 1 (ET) on WICR 88.7 fm, or stream on phone at WICR HD1. See the link below.

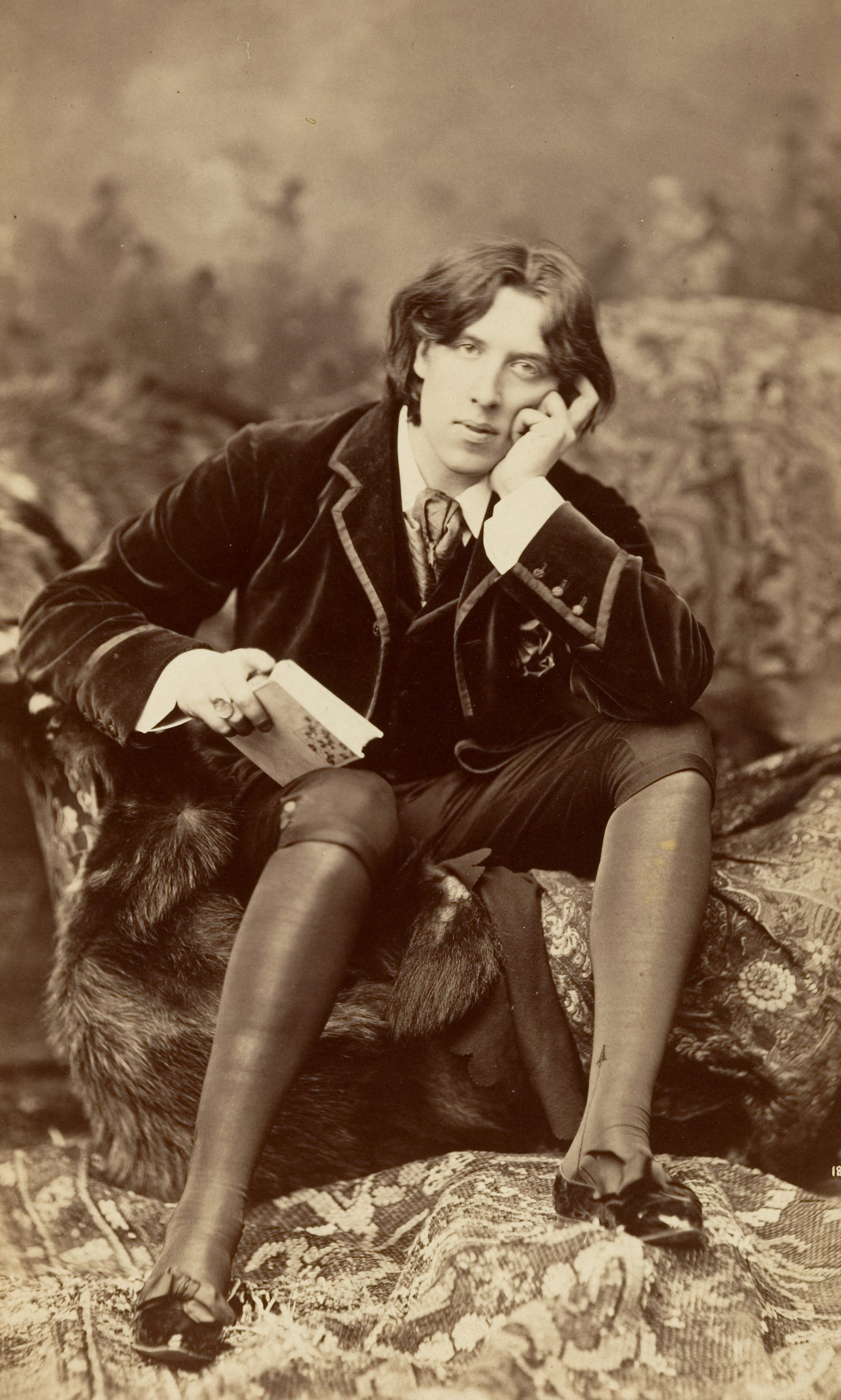

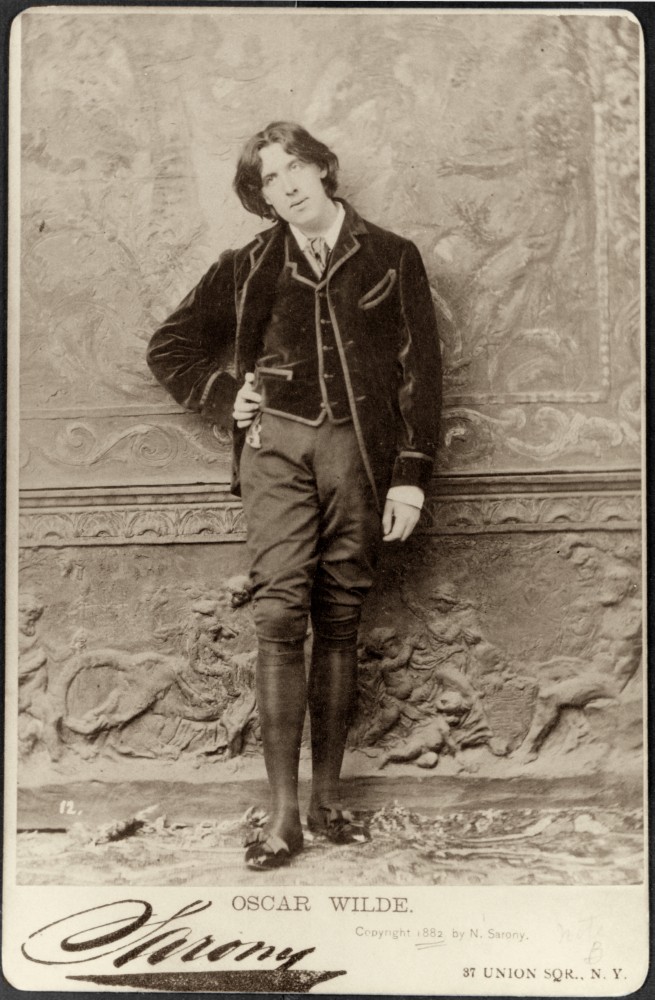

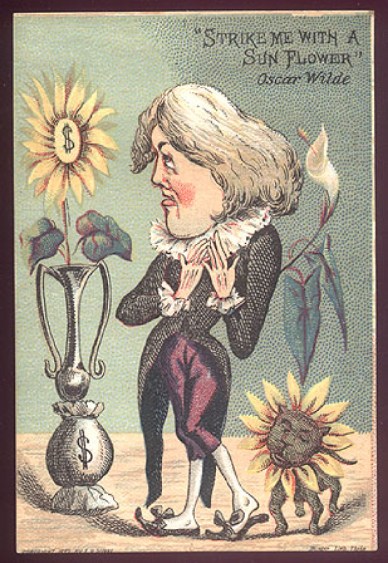

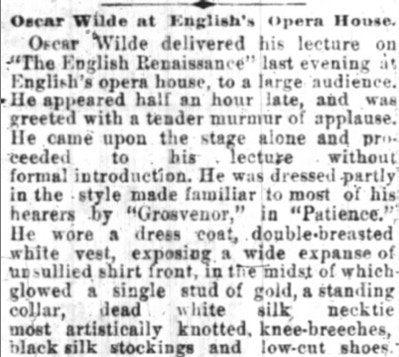

No less than five separate newspaper columns excoriated Wilde or his performance. The Indianapolis Journal newspaper said “We have grown sunflowers for many a year, suddenly, we are told there is a beauty in them our eyes have never been able to see. And hundreds of youths are smitten with the love of the helianthus. Alackaday! We must have our farces and our clowns. What fool next?” Soon, gaggles of admiring young men sporting sunflowers in their velvet lapels formed clubs known as “sunflower boys” to sit front and center at Wilde’s appearances. At Wilde’s other appearances, so many young street toughs interrupted Wilde’s shows that he sent advance notice to Denver that he would no longer act the gentleman and that he was “practicing with my new revolver by shooting at sparrows on telegraph wires from my car. My aim is as lethal as lighting. — O. Wilde.”

No less than five separate newspaper columns excoriated Wilde or his performance. The Indianapolis Journal newspaper said “We have grown sunflowers for many a year, suddenly, we are told there is a beauty in them our eyes have never been able to see. And hundreds of youths are smitten with the love of the helianthus. Alackaday! We must have our farces and our clowns. What fool next?” Soon, gaggles of admiring young men sporting sunflowers in their velvet lapels formed clubs known as “sunflower boys” to sit front and center at Wilde’s appearances. At Wilde’s other appearances, so many young street toughs interrupted Wilde’s shows that he sent advance notice to Denver that he would no longer act the gentleman and that he was “practicing with my new revolver by shooting at sparrows on telegraph wires from my car. My aim is as lethal as lighting. — O. Wilde.”

On his 1882 lecture tour of America drank elderberry wine with Walt Whitman in Camden (of whom he said, “I have the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips.”), conversed chillily with Henry James in Washington (who called Wilde “the most gruesome object I ever saw”), lectured in Saint Joseph, Missouri (two weeks after the death of Jesse James), called on an elderly Jefferson Davis at his Mississippi plantation (of whom Wilde inexplicably remarked, “The principles for which Jefferson Davis and the South went to war cannot suffer defeat.”), and fell prey to a con-man in New York’s Tenderloin (he lost $ 5,000 to legendary Gotham City conman Hungry Joe Lewis in a rigged Bunco game).

On his 1882 lecture tour of America drank elderberry wine with Walt Whitman in Camden (of whom he said, “I have the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips.”), conversed chillily with Henry James in Washington (who called Wilde “the most gruesome object I ever saw”), lectured in Saint Joseph, Missouri (two weeks after the death of Jesse James), called on an elderly Jefferson Davis at his Mississippi plantation (of whom Wilde inexplicably remarked, “The principles for which Jefferson Davis and the South went to war cannot suffer defeat.”), and fell prey to a con-man in New York’s Tenderloin (he lost $ 5,000 to legendary Gotham City conman Hungry Joe Lewis in a rigged Bunco game).