Original publish date: February 19, 2016

Original publish date: February 19, 2016

Remember the game “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon” that was so popular a few years back? It was a parlor game based on the concept that any two people on Earth are six or fewer acquaintance links apart. The winner is determined by the person able to use the least links to get to Kevin Bacon. Example: Someone draws the name Elvis Presley. Elvis was in the 1969 film CHANGE OF HABIT with Ed Asner. Asner was in the 1991 movie JFK with Kevin Bacon. Next player gets Will Smith. Smith and Jon Voight starred in ENEMY OF THE STATE… Jon Voight and Burt Reynolds starred in DELIVERANCE… Burt Reynolds and Demi Moore starred in STRIP TEASE…Demi Moore and Kevin Bacon starred in A FEW GOOD MEN . So Elvis wins.

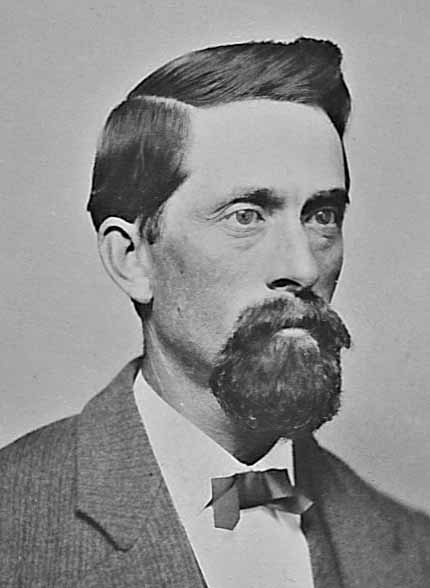

I sometimes find myself playing six degrees with two of my favorite subjects: Abraham Lincoln and Indiana. I also love historical trivia. This article involves both. John Mathews was an actor and childhood friend of Abraham Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth. Mathews grew up with Booth in Baltimore Maryland and remained a close friend right up to that fateful night in April of 1865. They had the same jet black hair and classic features, but Mathew lacked the style and charisma that made Booth the superstar who many considered the most handsome man in America at the time. In fact, Mathews was acting on stage at Ford’s Theatre the night his friend killed the President.

Sometime around 11:00 am on April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth left the National Hotel and went to Ford’s Theatre to pick up his mail. At Ford’s he learns that President Abraham Lincoln would be attending the evening performance of Our American Cousin. Booth paced around the theater in a trance for some time before he decided that this would be the perfect time to assassinate the president.

That afternoon, Booth sat down and wrote a letter to the editor of a Washington D.C. newspaper called the National Intelligencer. In it, he explained that his plans had changed from kidnapping Lincoln to assassinating Lincoln. He signed the letter not only with his own name but also three of his co-conspirators: Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, and David Herold. Then he got up and walked his rented horse down Fourteenth Street.

That afternoon, Booth sat down and wrote a letter to the editor of a Washington D.C. newspaper called the National Intelligencer. In it, he explained that his plans had changed from kidnapping Lincoln to assassinating Lincoln. He signed the letter not only with his own name but also three of his co-conspirators: Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, and David Herold. Then he got up and walked his rented horse down Fourteenth Street.

Around 4:00 pm, Booth runs into his old friend Mathews on the street near Willard’s Hotel. As it happens Mathews was playing the role of Richard Coyle in Our American Cousin that night. Booth greeted his friend with excited handshake, Mathews later recalled that Booth squeezed his hand so tightly that his nails left marks in his flesh. He gave Mathews the letter and asked him to deliver it to the National Intelligencer the next day. Booth got on his horse and rode off, passing General Ulysses S. Grant’s carriage along the way. Mathews, used to his friend’s odd behavior, tucked the letter into his coat pocket and thought no more about it.

Six hours later Booth enters Ford’s Theatre lobby around 10:07 P.M. He walks in the shadows along the curved back wall of the theatre up to the President’s box. Within minutes, Booth mortally wounds the President, jumps from the box 12 feet to the stage (breaking his leg in the process) and vanishes into the night. Inside the theatre, chaos ruled. Mathews and many of his fellow actors decided fairly quickly that the best thing they could do was to get out of there quick. Back then, actors were considered in the same vein as pickpockets, confidence men, rat catchers and prostitutes and they wanted nothing to do with the police. Those few actors who remained were quickly rounded up and jailed by the police. Harry Hawk, the actor who had been on stage at the moment of the shooting, wandered the streets of Washington aimlessly all night too afraid to go home.

In the chaos following the shot, Mathews retreated to his nearby boardinghouse. The streets were choked with people and soldiers guarded the entrance to every building. Mathews climbed the gutter to the open window of his upstairs room totally unaware that Booth’s letter was still secreted away in his overcoat pocket. As he removed his coat, the envelope dropped out with a pop onto the hardwood floor. Time stood still as a terrified Mathews stared at the unopen letter laying at his feet. “Great God,” he surely thought, this could be the instrument of my doom.

30-year-old Mathews picked up the envelope with the care and concern of a surgeon. He slowly turned it over in his hands, unsure of what to do. Finally, he decided to open the letter. While the true contents of the letter are known only by Mathews and Booth, Mathews claimed it was a detailed confession to the assassination. Mathews quickly destroyed the letter by throwing it into the fireplace after reading it. After all, no one wanted the authorities to believe that they were associated with the assassin, childhood friendships notwithstanding.

After watching the fires consume the murderous edict, Mathews climbed back out the window and nervously walked back to the place he knew best; Ford’s Theatre. John Mathews almost got himself hanged twice on assassination night. Two separate crowds tried to hang him based on his resemblance to Booth and because he was in the theatre that night. He escaped the first unscathed. The second time, the rope had already been placed around his neck when some soldiers rescued him. Eventually, Mathews was detained by the authorities; partly for his own safety and partly for interrogation.

In time, Mathews revealed his long association with Booth and the details of the mysterious letter. He tried to reconstruct the letter for authorities but strenuously proclaimed his innocence and complete ignorance of his friend’s murderous intentions. Despite his protestations, he was detained for several days as an accomplice. Luckily for Mathews, Booth read newspaper accounts smuggled to him while hiding in the pine thicket of the southern Maryland woods. He discovered that Mathews had not delivered his manifesto to the newspaper as promised. Booth recreated it for posterity in his diary and it would match, nearly word-for-word, Mathews account of the letter.

After his release, Mathews was so frightened that he thought briefly of changing his name, but relented. Although risky and unpopular, Mathews remained faithful to his friend Booth for the rest of his life. He told friends and fellow actors, his sole reason for burning the letter was to erase any evidence against his friend. Even three decades later, he referred to the country’s first presidential assassination as “the great mistake.”

Interesting to be sure, but what about the trivia and the six degrees? John Mathews lived upstairs at Petersen’s Boardinghouse, the house directly across the street from Ford’s Theatre where President Lincoln was taken after he was shot. Petersen often rented rooms to the stock actors playing at Ford’s. During the 1864-65 season both John Mathews and fellow actor Charles Warwick had previously rented the room Willie Clark was renting on April 14. It was in private Willie Clark’s room where Abraham Lincoln died at 8:22 am on April 15, 1865.

Booth knew both actors well enough that he often stopped and chatted with each of them there. A few accounts go so far as to claim that Booth himself spent the night in the Petersen house, possibly even in the room in which Lincoln died. What historians know for sure is that Mathews was boarding at the Petersen House on March 16th when he returned to find Booth stretched out on the bed, hands clasped behind his head calmly smoking a cigar while waiting for him. It was the very same bed in which Lincoln died less than a month later.

Apparently Booth visited Mathews and Warwick at the Petersen house and both rented the Lincoln death room on numerous occasions. Both actors recalled Booth visiting them there, stretching out on the bed, laughing and telling stories, chomping on a cigar or with his pipe hooked in his mouth. There are several unconfirmed claims that Mathews was actually staying in an upstairs room at the Petersen House on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. The accounts are speculative at best but tantalizing to be sure. If that were the case, then Mathews burned Booth’s confessional letter in a fireplace just feet away from the dying President.

Apparently Booth visited Mathews and Warwick at the Petersen house and both rented the Lincoln death room on numerous occasions. Both actors recalled Booth visiting them there, stretching out on the bed, laughing and telling stories, chomping on a cigar or with his pipe hooked in his mouth. There are several unconfirmed claims that Mathews was actually staying in an upstairs room at the Petersen House on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. The accounts are speculative at best but tantalizing to be sure. If that were the case, then Mathews burned Booth’s confessional letter in a fireplace just feet away from the dying President.

As for the six degrees? John Mathews is buried in the Actors Fund plot of Kensico cemetery in Valhalla, New York a few feet away from vaudevillian actor Pat Harrington, Sr. His son Pat, Jr. played handyman Dwayne Schneider in the TV show “One Day at a Time” that also starred Bonnie Franklin, Valerie Bertinelli and MacKenzie Phillips. The sitcom was based in Indianapolis. I win!

Original publish date: June 10, 2013

Original publish date: June 10, 2013 Sean Leslie Flynn, born May 31, 1971, made some forgettable films during his short movie career including the regrettable remake of his father’s classic “Captain Blood” featuring the predictable title “Son of Captain Blood”. When he “retired” from acting, Flynn signed a contract with Time Magazine. In a search for exceptional images, he attached himself to Special Forces units and even irregulars operating in remote areas.

Sean Leslie Flynn, born May 31, 1971, made some forgettable films during his short movie career including the regrettable remake of his father’s classic “Captain Blood” featuring the predictable title “Son of Captain Blood”. When he “retired” from acting, Flynn signed a contract with Time Magazine. In a search for exceptional images, he attached himself to Special Forces units and even irregulars operating in remote areas. On November 17, 1961, Rockefeller and Dutch anthropologist René Wassing were in a 40-foot dugout canoe about three miles from shore when their double pontoon boat was swamped and overturned into the Arafura Sea. Their two local guides swam for help and told the Anglos to stay put, for obvious reasons. After drifting for some time in the rolling waters off the coast of New Guinea, Rockefeller said to Wassing “I think I can make it”. Michael estimated that the catamaran boat was five miles from the shore. The current was against him, and he risked a confrontation with a shark or crocodile, but perhaps because he was a Rockefeller, the fabled family of industrialists, philanthropists and politicians, he decided to swim for it. Later it was determined that the capsized boat was closer to twelve miles off shore when Michael pushed off.

On November 17, 1961, Rockefeller and Dutch anthropologist René Wassing were in a 40-foot dugout canoe about three miles from shore when their double pontoon boat was swamped and overturned into the Arafura Sea. Their two local guides swam for help and told the Anglos to stay put, for obvious reasons. After drifting for some time in the rolling waters off the coast of New Guinea, Rockefeller said to Wassing “I think I can make it”. Michael estimated that the catamaran boat was five miles from the shore. The current was against him, and he risked a confrontation with a shark or crocodile, but perhaps because he was a Rockefeller, the fabled family of industrialists, philanthropists and politicians, he decided to swim for it. Later it was determined that the capsized boat was closer to twelve miles off shore when Michael pushed off. Original publish date: June 3, 2013

Original publish date: June 3, 2013 My eyes are always drawn towards the upper second-floor balcony and a wrought iron gate contained there. Upon closer examination, one notices that there is a small piece of the ornate iron fencing that is broken. The balcony railing has been maintained in a state of “arrested decay” to honor Lincoln’s rambunctious boys, Willie and Tad, who allegedly broke off a piece of the ornamentation while playing on the balcony. While I have a deep affinity for Abraham Lincoln the man, I don’t think I’d aspire to adopt the parenting qualities of Abraham Lincoln, the father.

My eyes are always drawn towards the upper second-floor balcony and a wrought iron gate contained there. Upon closer examination, one notices that there is a small piece of the ornate iron fencing that is broken. The balcony railing has been maintained in a state of “arrested decay” to honor Lincoln’s rambunctious boys, Willie and Tad, who allegedly broke off a piece of the ornamentation while playing on the balcony. While I have a deep affinity for Abraham Lincoln the man, I don’t think I’d aspire to adopt the parenting qualities of Abraham Lincoln, the father. Lincoln’s own children, however, spent their days playing with their toys in their carpeted sitting room or attending school. Both luxuries not available to young Abe Lincoln. While Abe grew up in poverty, Mary came from a prominent, wealthy Kentucky family-the Todds. Although she grew up in considerable luxury, her childhood was affected by the loss of her mother, emotional alienation from her father and disenfranchisement from her step-mother. Mary’s unhappy childhood caused her to dote on her children as equally as her husband but for vastly different reasons. In short, most people would consider the Lincoln children to be perfect “brats”. Mary Lincoln later recalled that Lincoln “was very – exceedingly indulgent to his children… He always said it is my pleasure that my children are free, happy and unrestrained by parental tyranny. Love is the chain whereby to bind a child to its parents.”

Lincoln’s own children, however, spent their days playing with their toys in their carpeted sitting room or attending school. Both luxuries not available to young Abe Lincoln. While Abe grew up in poverty, Mary came from a prominent, wealthy Kentucky family-the Todds. Although she grew up in considerable luxury, her childhood was affected by the loss of her mother, emotional alienation from her father and disenfranchisement from her step-mother. Mary’s unhappy childhood caused her to dote on her children as equally as her husband but for vastly different reasons. In short, most people would consider the Lincoln children to be perfect “brats”. Mary Lincoln later recalled that Lincoln “was very – exceedingly indulgent to his children… He always said it is my pleasure that my children are free, happy and unrestrained by parental tyranny. Love is the chain whereby to bind a child to its parents.” Original publish date: December 14, 2013

Original publish date: December 14, 2013 On November 18, 1863, Lincoln wrote a note explaining that Johnson would travel with him to Gettysburg for the dedication of the soldiers’ cemetery. The note, written to the Treasury Department, asks to borrow Johnson’s services for a “whole day or two” and closes simply: “William goes with me.” Mrs. Lincoln remained at the White House attending to their son Tad. Once in Gettysburg. After delivering his address, Lincoln began to feel ill and while aboard the return train to Washington “lay in a relaxed position with a wet towel across his head,” placed there by Johnson. The details of the President’s recovery were covered in detail in part III of the November Lincoln at Gettysburg series. Although the President would recover, Mr. Lincoln may have unwittingly passed the illness on to his valet.

On November 18, 1863, Lincoln wrote a note explaining that Johnson would travel with him to Gettysburg for the dedication of the soldiers’ cemetery. The note, written to the Treasury Department, asks to borrow Johnson’s services for a “whole day or two” and closes simply: “William goes with me.” Mrs. Lincoln remained at the White House attending to their son Tad. Once in Gettysburg. After delivering his address, Lincoln began to feel ill and while aboard the return train to Washington “lay in a relaxed position with a wet towel across his head,” placed there by Johnson. The details of the President’s recovery were covered in detail in part III of the November Lincoln at Gettysburg series. Although the President would recover, Mr. Lincoln may have unwittingly passed the illness on to his valet. During that Chicago Tribune interview, the journalist found Abraham Lincoln busy counting greenbacks. The money belonged to Johnson who was in the hospital, so sick that he could not even draw his pay. “This, sir, is something out of my usual line,” the president told the reporter, “but a president of the United States has a multiplicity of duties not specified in the Constitution or acts of Congress. This is one of them. This money belongs to a poor negro [Johnson] who is a porter in one of the departments (the Treasury) and who is at present very bad with the smallpox. He did not catch it from me, however; at least I think not. He is now in hospital, and could not draw his pay because he could not sign his name. I have been at considerable trouble to overcome the difficulty and get it for him, and have at length succeeded in cutting red tape, as you newspaper men say. I am now dividing the money and putting by a portion labeled, in an envelope, with my own hands, according to his wish.”

During that Chicago Tribune interview, the journalist found Abraham Lincoln busy counting greenbacks. The money belonged to Johnson who was in the hospital, so sick that he could not even draw his pay. “This, sir, is something out of my usual line,” the president told the reporter, “but a president of the United States has a multiplicity of duties not specified in the Constitution or acts of Congress. This is one of them. This money belongs to a poor negro [Johnson] who is a porter in one of the departments (the Treasury) and who is at present very bad with the smallpox. He did not catch it from me, however; at least I think not. He is now in hospital, and could not draw his pay because he could not sign his name. I have been at considerable trouble to overcome the difficulty and get it for him, and have at length succeeded in cutting red tape, as you newspaper men say. I am now dividing the money and putting by a portion labeled, in an envelope, with my own hands, according to his wish.” Original publish date: March 20, 2014

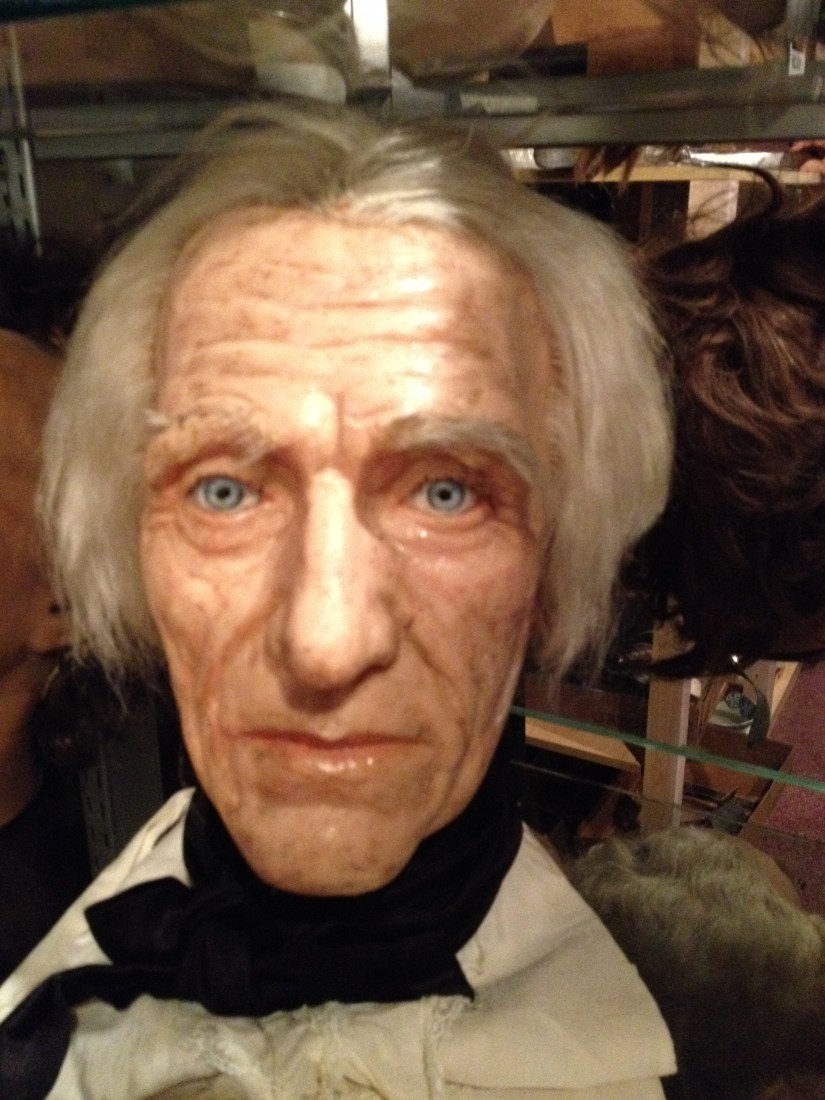

Original publish date: March 20, 2014 On Saturday, March 15th the museum’s contents were sold to the public at auction. The sale included 95 Civil War wax figures and the accouterments used to illustrate each scene. In it’s half century of service the museum saw over 8 million visitors walk through the turnstiles, now lot # 265 in this very special auction.

On Saturday, March 15th the museum’s contents were sold to the public at auction. The sale included 95 Civil War wax figures and the accouterments used to illustrate each scene. In it’s half century of service the museum saw over 8 million visitors walk through the turnstiles, now lot # 265 in this very special auction. As I finished perusing the auction lots, I halted at an area tucked away in a back corner of the hall. This dimly lit crook featured tiered shelves upon which rested approximately 40 disembodied heads. Some of the heads were recognizable to me; Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Jackson. On a shelf nearby lay a pile of arms, legs and hands. Some of these body parts, in keeping with the brutality of the Civil War, were spattered with blood stains. Seeing these, I turned to my wife and said “Now these have the potential to go sky high.”

As I finished perusing the auction lots, I halted at an area tucked away in a back corner of the hall. This dimly lit crook featured tiered shelves upon which rested approximately 40 disembodied heads. Some of the heads were recognizable to me; Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Jackson. On a shelf nearby lay a pile of arms, legs and hands. Some of these body parts, in keeping with the brutality of the Civil War, were spattered with blood stains. Seeing these, I turned to my wife and said “Now these have the potential to go sky high.” The synchronicity of the moment was not lost on me as, outside just yards away, bulldozers busily cleared out the massive football field sized blacktop parking lot. It had once served the old visitor’s center (torn down in 2008) and Cyclorama building, built the same year as the wax museum and torn down in March 2013. In the past 25 years I watched as other tourist landmarks disappeared from the borough including the Lincoln Room Museum, The National Tower, and now, the Wax Museum.

The synchronicity of the moment was not lost on me as, outside just yards away, bulldozers busily cleared out the massive football field sized blacktop parking lot. It had once served the old visitor’s center (torn down in 2008) and Cyclorama building, built the same year as the wax museum and torn down in March 2013. In the past 25 years I watched as other tourist landmarks disappeared from the borough including the Lincoln Room Museum, The National Tower, and now, the Wax Museum. Undoubtedly the happiest person in the room that day was a young woman named Kim Yates. She was hard to miss. Towards the end of the auction she bid on, and won, the last wax figure in the catalog. Suddenly, the previously sedate young lady began to scream wildly and jump around the room. One of the ringmen sidled over to me, after noting the look of obvious surprise on my face, and whispered, “She’s never bid in an auction before.”

Undoubtedly the happiest person in the room that day was a young woman named Kim Yates. She was hard to miss. Towards the end of the auction she bid on, and won, the last wax figure in the catalog. Suddenly, the previously sedate young lady began to scream wildly and jump around the room. One of the ringmen sidled over to me, after noting the look of obvious surprise on my face, and whispered, “She’s never bid in an auction before.”