Original publish date: October 22, 2020. https://weeklyview.net/2020/10/22/the-mumler-abraham-lincoln-ghost-photo/

https://www.digitalindy.org/digital/collection/twv/id/3900/rec/104

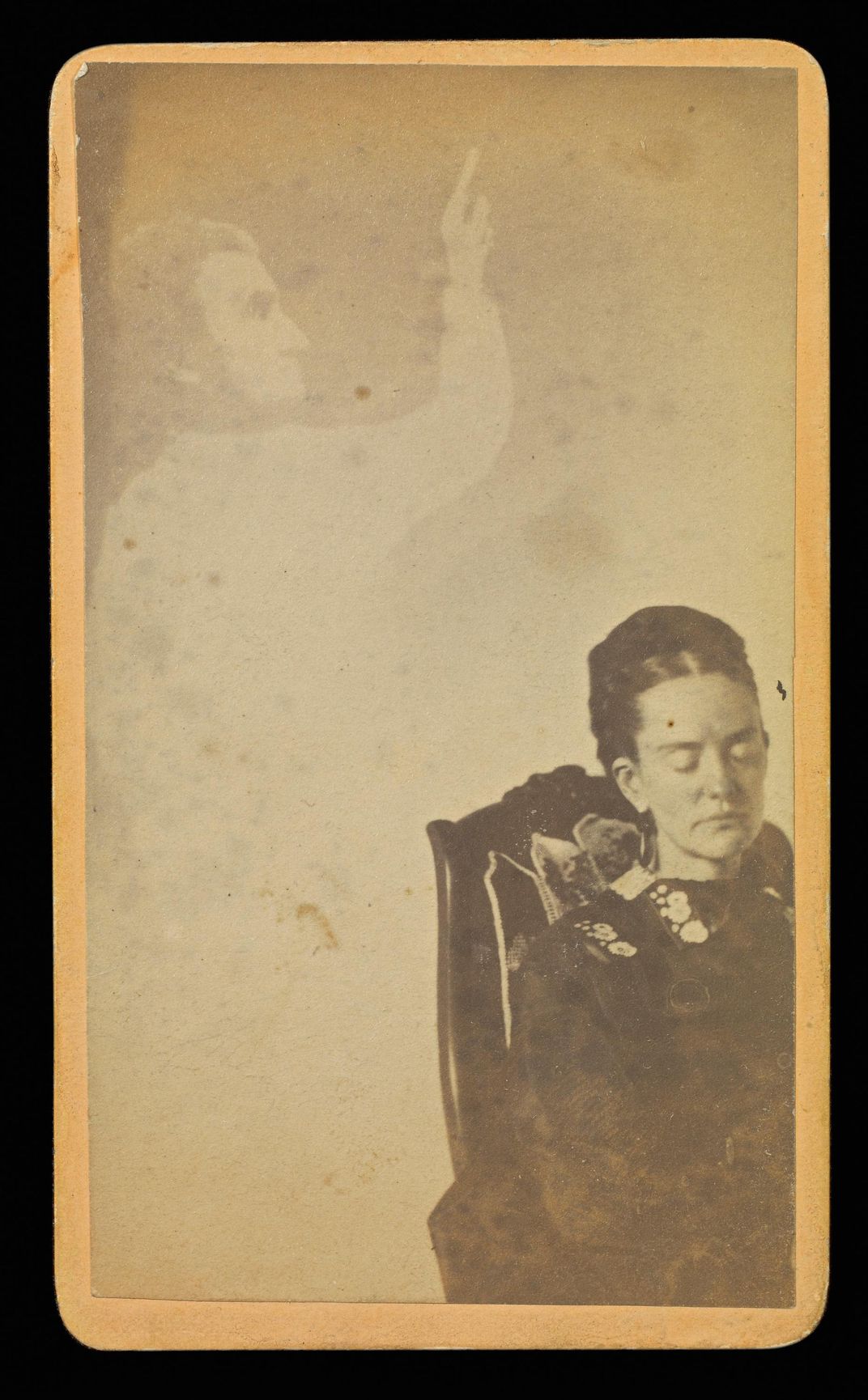

Last Saturday before the Irvington ghost tours, one of our volunteers, Alex McFarland, initiated a conversation that seemed to be a perfect topic for the evening: the Abraham Lincoln ghost photo. Known officially as the “Mumler photos”, these were a series of posed studio photographs, not unlike any old-time photo, usually in Carte de Visite (or CDV) form, that can be found at any antique show, shop, or mall today. The difference is, that Mumler’s photos had the visual image of a ghost in them. The most famous of the Mumler photos features widowed First Lady Mary Lincoln with her deceased husband, President Abraham Lincoln.

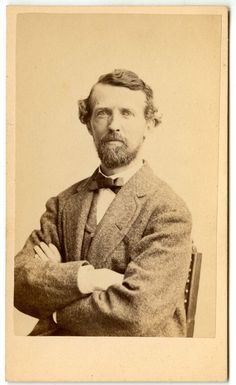

William H. Mumler

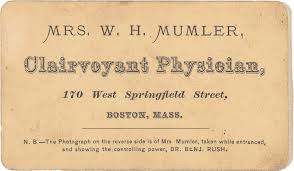

William H. Mumler (1832-1884) was a well-known Boston photographer who claimed to be a “medium for taking spirit photographs.” Mumler was part of the growing phenomenon of spiritual manifestations introduced in 1848 by the Fox sisters of Hydesville, N.Y. The three sisters held séances at their home (near Newark, N.J.), that featured spirit rappings and table tippings in response to their queries. Their amazing “abilities” caused a sensation that spread across the country. With its long history of highly-intelligent, intellectually curious populace, Boston became an epicenter for the movement attracting spiritualists, mediums, and psychics from all over to the mysterious world of the “higher plane.”

In 1871, the camera was still in its infancy. The technology had graduated from metal to glass to paper photos readily available and affordable to the general public like never before. The country was still mourning from Civil War losses, in some cases having lost entire male lines of families and large portions of towns and communities. The loss of loved ones was still fresh and many turned to any means necessary to see and talk to their loved ones one last time. Mumler’s promise of contact in the form of visual evidence drew flocks of true believers to his studio at 170 West Springfield Street in this city historians called the “Cradle of Liberty.”

In February of 1872, seven years after Lincoln’s assassination, a still grieving Mary Lincoln arrived at William Mumler’s Boston Studio to have her picture made. Dressed in mourning, she gave the photographer a false name (‘Mrs. Lindall”) and kept her face concealed behind a black veil. In 1875, Mumler recalled in his autobiography, “I requested her to be seated, went into my darkroom, and coated a plate. When I came out I found her seated with her veil still over her face. I asked if she intended to have her picture taken with her veil. She replied, ‘When you are ready, I will remove it.’” The widow Lincoln was used to dealing with charlatans and knew how to prevent their tricks.

The reason she landed at Mumler’s studio was because her dead husband had appeared to her at a séance earlier in Boston. The medium told her she should visit Mumler’s studio because the photographer could capture the shadows of the dead on photographic negatives. Mumler always claimed that he did not recognize his subject until after he developed the negative. And then only after he recognized the image of the martyred President did he realize it was Mary Todd Lincoln. His visitor just may have been the most vulnerable woman in America, shattered by death and loss for the past two decades.

Mary never recovered from her husband’s assassination six years before and the loss of three of her four sons, all dead before their 18th birthdays. Even before her husband’s death, Mary Lincoln had embraced spiritualism, the belief that the spirits of the dead can be contacted through mediums. Reputedly going so far as hosting seances in the White House and visiting mediums in Georgetown and D.C., sometimes accompanied by the President himself. So her visit to the studio, today located near historic Frederick Douglass Square in Boston, was unsurprising and predictable. It should also come as no surprise that the photo, the greatest presidential ghost photo ever known, is a fake.

Mary’s visit to William Mumler’s studio (one of five Boston studio locations he occupied during the 1860s-70s and 80s) stands out as one of the grand hoaxes of the Spiritualist period. The distraught first lady must have been satisfied, even consoled by the image, but to our practiced modern eyes, this photograph of Mary Lincoln remains a touching, if sadly preposterous, fake. Nonetheless, it was Mumler’s most famous portrait. Mumler’s Lincoln image is his most reproduced photograph, and it is believed to be the last photo ever taken of Mary before she died in 1882.

The story of Mumler’s spirit photography began as an accident and turned into a joke. In 1861 the 29-year-old jewelry engraver was living in Boston and experimenting with the new art of photography as a hobby. In his autobiography, The Personal Experiences of William H. Mumler in Spirit Photography, Mumler claimed his discovery was made while developing a self-portrait. While the plate was soaking in the tray of toxic chemicals, he noticed the mysterious form of a young girl slowly materialize on the negative. Amused and mystified, Mumler printed this curiosity and showed it around to friends, claiming that it was the ghost of a dead cousin. Mumler, a man of “a jovial disposition, always ready for a joke,” decided to show the photo to his spiritualist friends, pretending that his picture was a genuine impression from beyond the grave.

The Boston psychics fell for the gag and soon Mumler’s ghost photos were circulating around the city. It became an instant sensation and once Mumler’s photo was published in The Banner of Light and other spiritualist newspapers, he became an instant celebrity. The “spirit cousin” was nothing more than the transfer residue of an earlier negative made with the same plate, but it was declared a miracle and Mumler the jeweler became heralded as the “oracle of the camera”. Mumler soon left his job as a jewelry engraver and opened his own photography business full-time.

Here’s the scam. On arrival, the subject of the photo was greeted by William’s wife Hannah, she would chat up the client who would invariably reveal who the spirits were that they wished to appear in their sitting. Hannah had some clairvoyant abilities of her own and she often offered her own intuitions about the spirits surrounding her husband’s clients, resulting in the client’s unwittingly revealing more precise information. All while William Mumler was eavesdropping from the adjoining room. Part of his con included a “vacuum tube” that glowed as an electrical current was run through it which he claimed was a special force he then channeled into the camera. It was P.T. Barnum-style showmanship pure and simple.

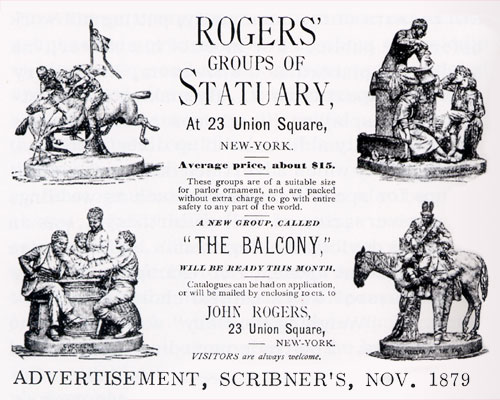

For this special ability, Mumler’s fees were extravagant. At the height of his fame, Mumler charged $10 for a dozen photographs, roughly five times the average rate. Worse, there was no guarantee that any spirits would appear. If Mumler or his wife sensed a particular vulnerability in their subject, the spirits would not appear in the photos. Clients were encouraged to make repeated trips to Mumler’s studio before they were blessed with a true spirit photograph. If the high fee was ever questioned, “The spirits,” Mumler answered, “did not like the throng.”

Boston’s other photographers were not impressed by Mumler’s ghost photos. James Black, one of Boston’s premiere photographers famous for his aerial views of the city taken from the perspective of a hot air balloon, was convinced that Mumler was cheating. He set out to catch him at it. Black bet Mumler $50 that he could discover his secret. Black examined Mumler’s camera, plate and processing system, and even went into the darkroom with him. In his autobiography, Mumler described Black’s reaction when a ghostlike image emerged on the negative right before the doubter’s eyes as, “Mr. B., watching with wonderstricken eyes…exclaimed, ‘My God! Is it possible?’”

P.T. Barnum.

Of the incident, Mumler later recalled, “Another form became apparent, growing plainer and plainer each moment, until a man appeared, leaning his arm upon Mr. Black’s shoulder.” The man later eulogized as “an authority in the science and chemistry of his profession” then watched “with wonder-stricken eyes” as the two forms took on a clarity unsettling in its intimacy. Despite the best efforts of countless investigators, no one was able to determine exactly how Mumler created his apparitions. With the photographic elite unable to debunk Mumler’s ghost photos, hoards of desperate souls flocked to Mumler’s studio-including a grieving Mary Lincoln and the master of all hoaxes, P.T. Barnum himself.

Soon Mumler’s pictures became the subject of great speculation among his peers from all over the country. In 1863 noted Boston scientist, physician, and avid photographer Oliver Wendell Holmes not only gave step-by-step instructions on how to obtain a double exposure in an essay for the Atlantic Monthly, but he also contemplated the popularity of Mumler’s pictures. “Mrs. Brown, for instance, has lost her infant, and wishes to have its spirit-portrait taken,” Holmes wrote. “It is enough for the poor mother, whose eyes are blinded with tears, that she sees a print of drapery like an infant’s dress, and a rounded something, like a foggy dumpling, which will stand for a face…An appropriate background for these pictures is a view of the asylum for feeble-minded persons…and possibly, if the penitentiary could be introduced, the hint would be salutary”

Further confounding the experts was the fact that the apparitions seen in a Mumler photograph had human features, lifelike gestures, and filmy interactive forms. They are translucent spirits, not hard-edged ghosts. That was the secret of a Mumler ghost photo. To mediums, psychics, and spiritualists, Mumler’s photos depicted what they believed: that the afterlife was a paradise, simply the next step in human existence, albeit on a higher plain. All questions of process and motives aside, Mumler’s subjects were satisfied with the results. Distraught parents saw visions of children gone for years. Grieving widows saw their husbands one more time and widowers looked into the eyes of deceased wives once again.

Eventually, Mumler was a victim of his own vanity and the third deadly sin of avarice: aka Greed. The more people that showed up, the more Mumler had to perform. Some prominent Boston spiritualists, once avid supporters of Mumler’s ability, began to examine the ghost photos more closely only to discover that some of the “spirits” in the images were still quite alive. The ragman, the butcher, the schoolteacher, the cop. These were normal people walking the streets of Boston, all past subjects of Mumler’s “straight” photo studio sessions utilized by Mumler in the photographs of strangers. Eventually, Mumler’s business in Boston fell off.

He died on May 16, 1884 holding patents on a number of innovative photographic techniques, including Mumler’s Process, which allowed publishers to directly reproduce photographic illustrations in newspapers, periodicals, magazines, and books. Mumler’s skill as a photographer was only rivaled by his talent as a con artist, but he never really experienced any accumulated wealth from his labors. Mumler maintained to the end that he was “only a humble instrument” for the revelation of a “beautiful truth.” To further confuse matters, Mumler destroyed all of his negatives shortly before he died. William Mumler’s photographs may be products of pure hoaxing, but the question of whether technology is capable of catching spirits on film remains with us to this day. Search the web on any given day and you will see photos of every type captured by cameras of every description. Security cameras, ring doorbells, digital images, and cellphones continue to capture photos of mysterious orbs, mists, apparitions, shadows, dancing lights, and unexplainable phenomenon of every description. The allure of capturing a ghost on film, especially that which is invisible to the naked eye, may have begun with William Mumler but it continues to this day.

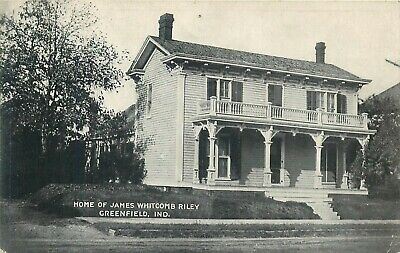

Although Lincoln and Riley died a half-century apart, the men had much in common. The two were considered the state’s most famous Hoosiers (that is until John Dillinger died in 1934) and their names were often linked in speeches, newspaper articles, books and periodicals in the first fifty years of the 20th century. One of my favorite quotes found while searching the virtual stacks of old newspapers comes from the July 20, 1941 Manhattan Kansas Morning Chronicle: “If you want to succeed in life, you might run a better chance if you live in a house with green shutters. Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain and James Whitcomb Riley all lived in such houses.” Lincoln and Riley epitomized everything that was good about being a Hoosier, right down to the color of their green window shutters.

Although Lincoln and Riley died a half-century apart, the men had much in common. The two were considered the state’s most famous Hoosiers (that is until John Dillinger died in 1934) and their names were often linked in speeches, newspaper articles, books and periodicals in the first fifty years of the 20th century. One of my favorite quotes found while searching the virtual stacks of old newspapers comes from the July 20, 1941 Manhattan Kansas Morning Chronicle: “If you want to succeed in life, you might run a better chance if you live in a house with green shutters. Abraham Lincoln, Mark Twain and James Whitcomb Riley all lived in such houses.” Lincoln and Riley epitomized everything that was good about being a Hoosier, right down to the color of their green window shutters.

Oldroyd, a thrice-wounded Civil War veteran, collector, curator and author, is perhaps the father of the house museum in America. One of Oldroyd’s books, a compilation of poems entitled, “The Poets’ Lincoln— Tributes In Verse To The Martyred President”, was published in 1915. James Whitcomb Riley’s poem, A Peaceful Life with the name “Lincoln” in parenthesis as a sub-title can be found there on page 31. In Oldroyd’s version, the first line differs from Riley’s original version. Riley’s handwritten original (found today in the archives of the Lilly Library on the Bloomington campus of Indiana University) begins: “Peaceful Life:-toil, duty, rest-“. Oldroyd’s book version begins; “A peaceful life —just toil and rest—.” Interestingly, the Oldroyd version has become the standard. And there you have it. Oldroyd’s influence is subtle, his name largely unknown, yet he stays with us to this day.

Oldroyd, a thrice-wounded Civil War veteran, collector, curator and author, is perhaps the father of the house museum in America. One of Oldroyd’s books, a compilation of poems entitled, “The Poets’ Lincoln— Tributes In Verse To The Martyred President”, was published in 1915. James Whitcomb Riley’s poem, A Peaceful Life with the name “Lincoln” in parenthesis as a sub-title can be found there on page 31. In Oldroyd’s version, the first line differs from Riley’s original version. Riley’s handwritten original (found today in the archives of the Lilly Library on the Bloomington campus of Indiana University) begins: “Peaceful Life:-toil, duty, rest-“. Oldroyd’s book version begins; “A peaceful life —just toil and rest—.” Interestingly, the Oldroyd version has become the standard. And there you have it. Oldroyd’s influence is subtle, his name largely unknown, yet he stays with us to this day.

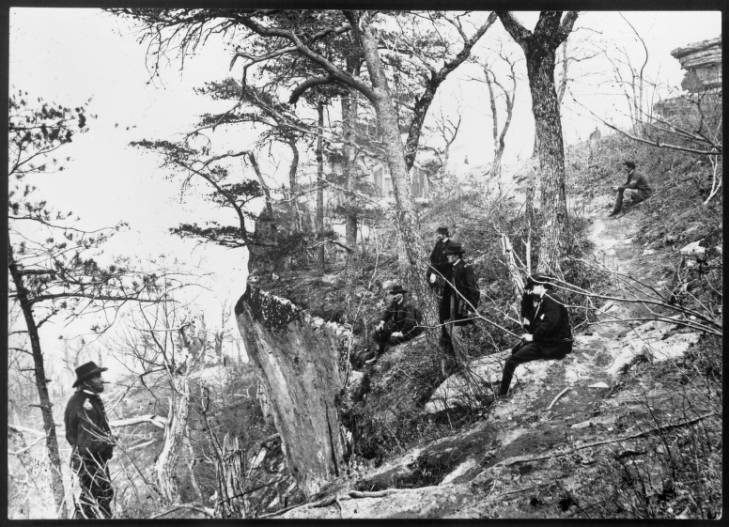

Grant immediately relieved Rosecrans in Chattanooga and replaced him with Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, soon to be known as “The Rock of Chickamauga”. Devising a plan known as the “Cracker Line”, Thomas’s chief engineer, William F. “Baldy” Smith opened a new supply route to Chattanooga, helping to feed the starving men and animals of the Union army. Upon re-provisioning and reinforcing, the morale of Union troops lifted and in late November, they went on the offensive. The Battles for Chattanooga ended with the capture of Lookout Mountain, opening the way for the Union Army to invade Atlanta, Georgia, and the heart of the Confederacy.

Grant immediately relieved Rosecrans in Chattanooga and replaced him with Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, soon to be known as “The Rock of Chickamauga”. Devising a plan known as the “Cracker Line”, Thomas’s chief engineer, William F. “Baldy” Smith opened a new supply route to Chattanooga, helping to feed the starving men and animals of the Union army. Upon re-provisioning and reinforcing, the morale of Union troops lifted and in late November, they went on the offensive. The Battles for Chattanooga ended with the capture of Lookout Mountain, opening the way for the Union Army to invade Atlanta, Georgia, and the heart of the Confederacy.

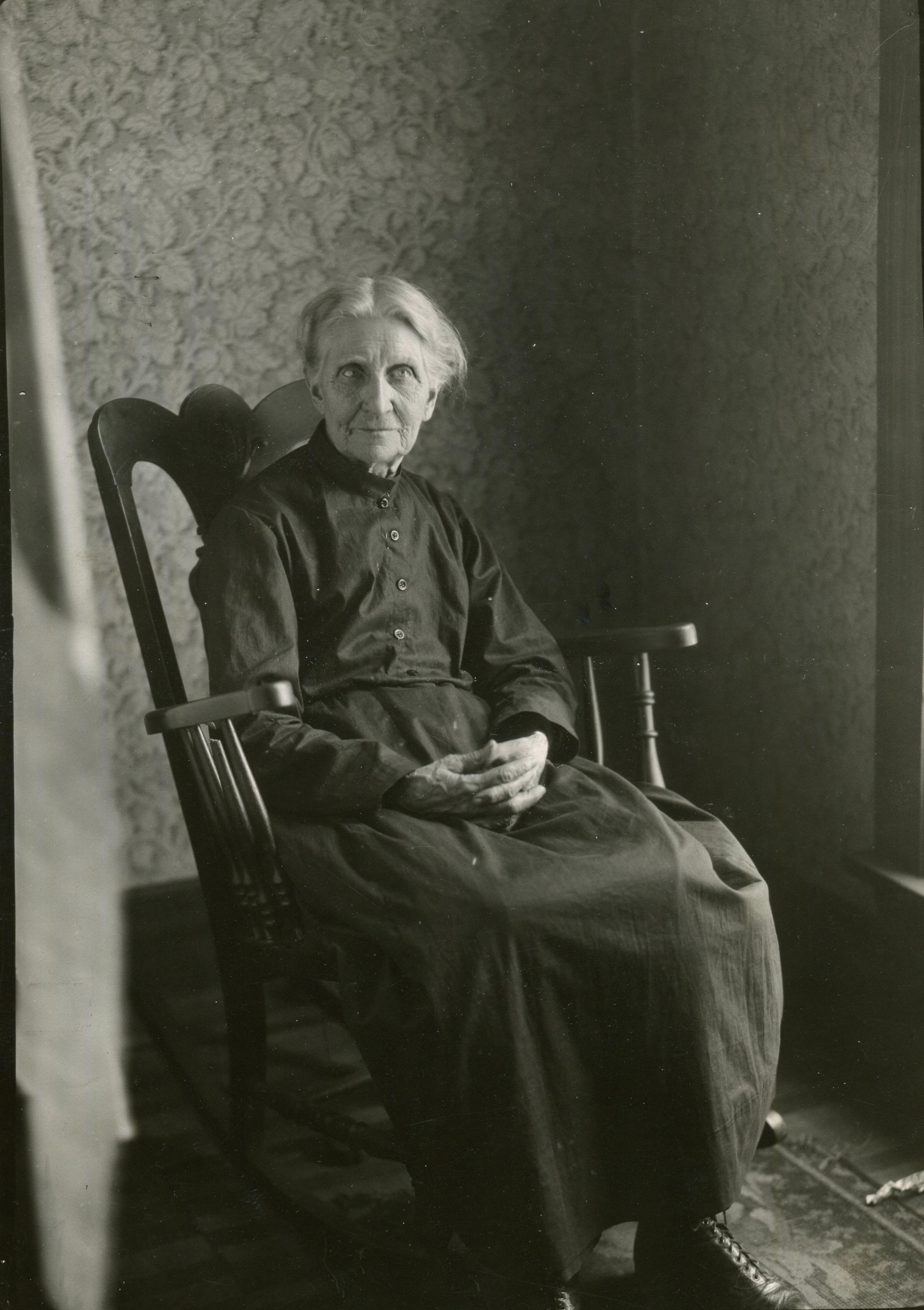

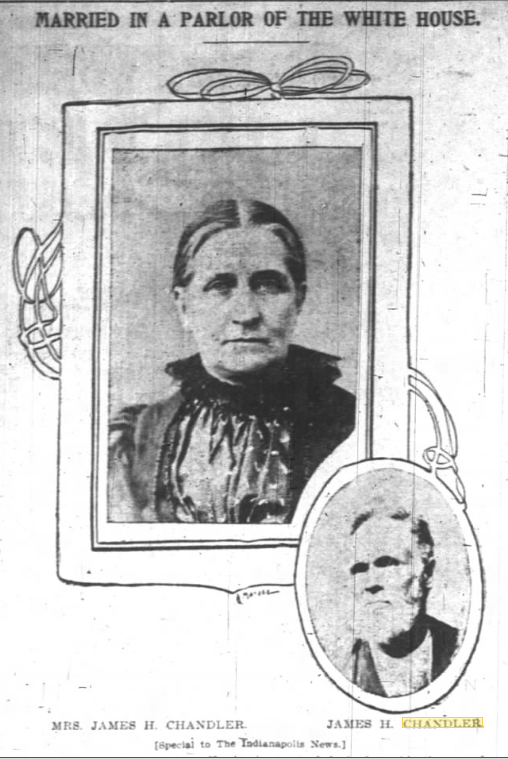

After the minister’s arrived, Lincoln rang a bell and then led the wedding party into a big room, Elizabeth recalled. The president stood alongside the minister and not only did he give the bride away but also acted as the groom’s best man. Elizabeth recalled how he smiled throughout the ceremony. She stated that a Cabinet member stood up with them, but couldn’t recall his name or that of the minister. Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln were the first to shake the newlyweds’ hands. Elizabeth’s most vivid recollection of the nuptials was how scared she was. The president chatted with them awhile and then returned to his office with the unnamed Cabinet member. Elizabeth had worn a plain white cashmere dress for the ceremony. Afterwards, the couple was taken to separate rooms in the White House to change clothes, where Elizabeth changed into a navy blue cashmere dress.

After the minister’s arrived, Lincoln rang a bell and then led the wedding party into a big room, Elizabeth recalled. The president stood alongside the minister and not only did he give the bride away but also acted as the groom’s best man. Elizabeth recalled how he smiled throughout the ceremony. She stated that a Cabinet member stood up with them, but couldn’t recall his name or that of the minister. Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln were the first to shake the newlyweds’ hands. Elizabeth’s most vivid recollection of the nuptials was how scared she was. The president chatted with them awhile and then returned to his office with the unnamed Cabinet member. Elizabeth had worn a plain white cashmere dress for the ceremony. Afterwards, the couple was taken to separate rooms in the White House to change clothes, where Elizabeth changed into a navy blue cashmere dress.