Original publish date March 23, 2023. https://weeklyview.net/2023/03/23/in-search-of-ann-rutledge-lincolns-lost-love/

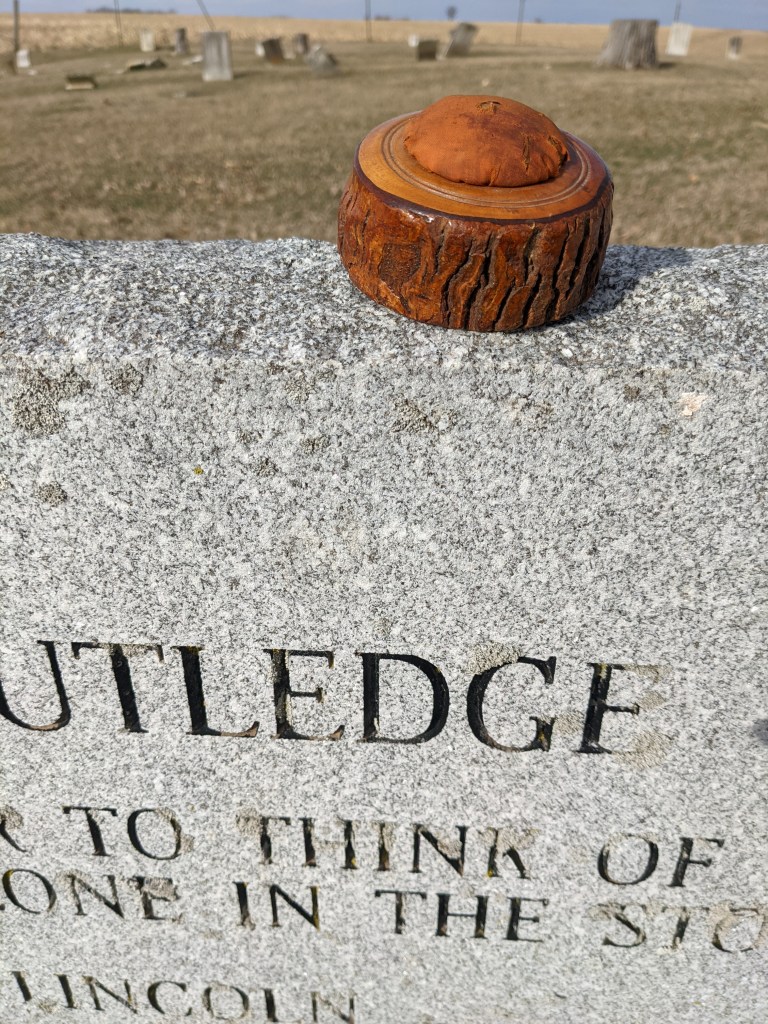

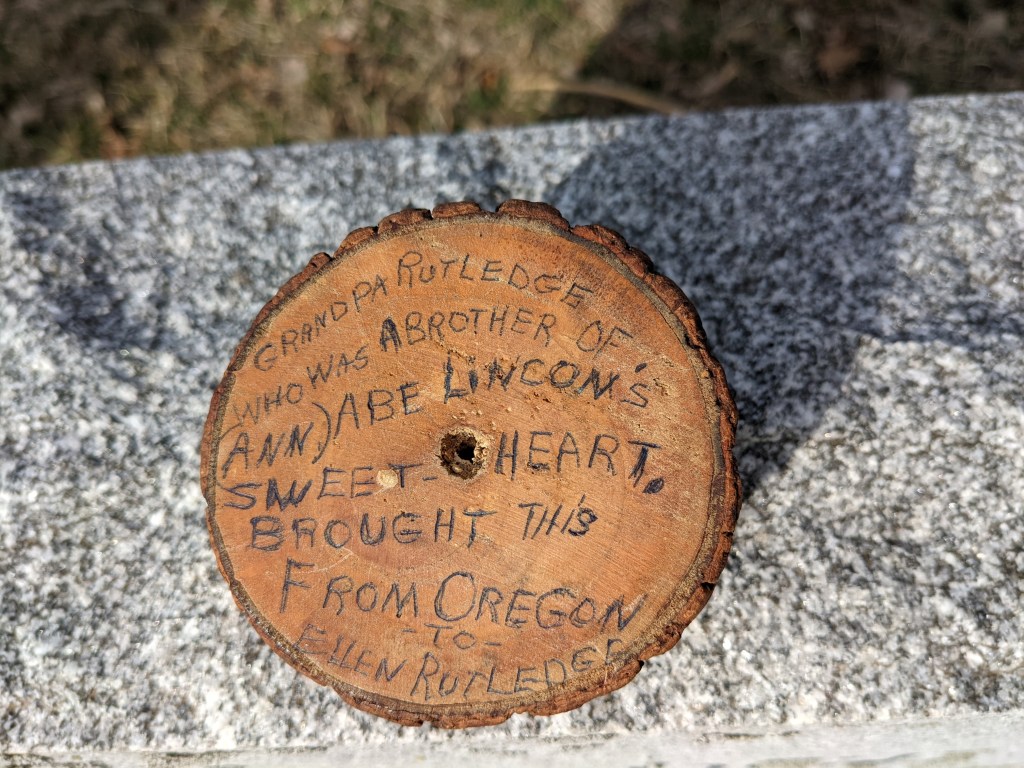

(Author’s trinket explained below)

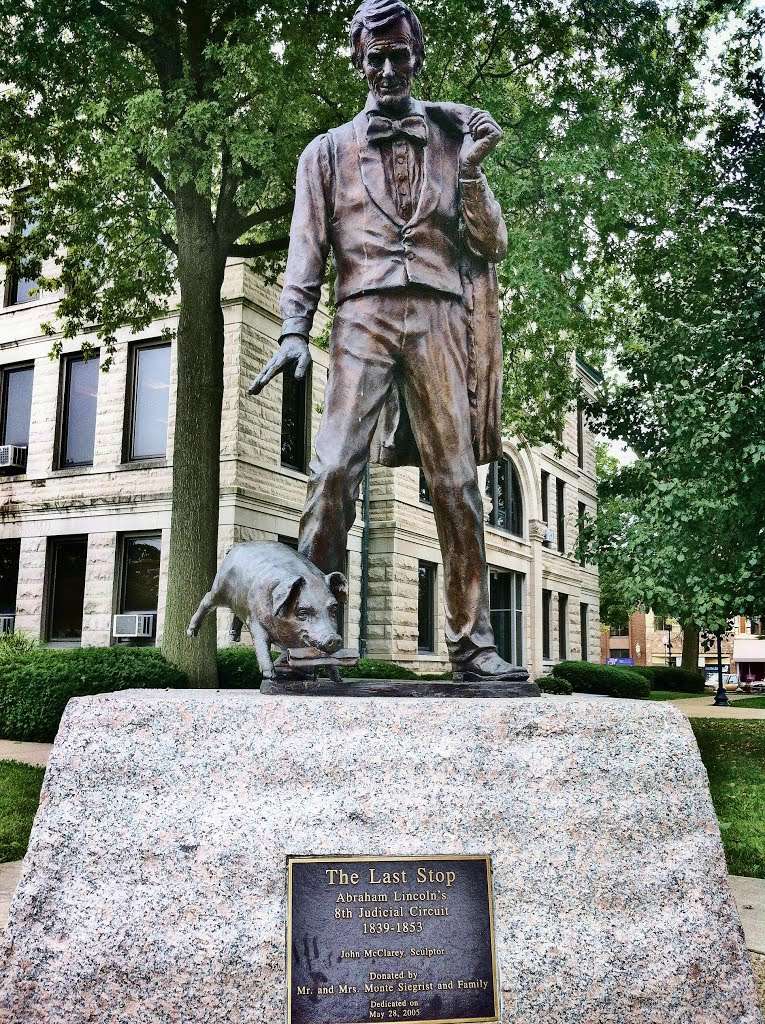

On March 1 I visited Springfield Illinois while working on an ongoing book project. My wife Rhonda wanted me out of the house for a couple of days for heavy spring cleaning. So I took advantage of an opportunity to visit some of the places I had long wished to visit but never seemed to get to. I visited a few of the markers on Lincoln’s 400-mile 8th judicial court circuit that he regularly traveled as a young lawyer during the 1840s and 1850s. I visited the courthouse in Taylorsville, where Lincoln’s court proceedings were often interrupted by the sounds of squealing pigs rooting under the courthouse floor — once so loudly that Lincoln asked the judge for a “writ of quietus” to calm the commotion. As you might imagine, Illinois is full of interesting Lincoln sites off the beaten path.

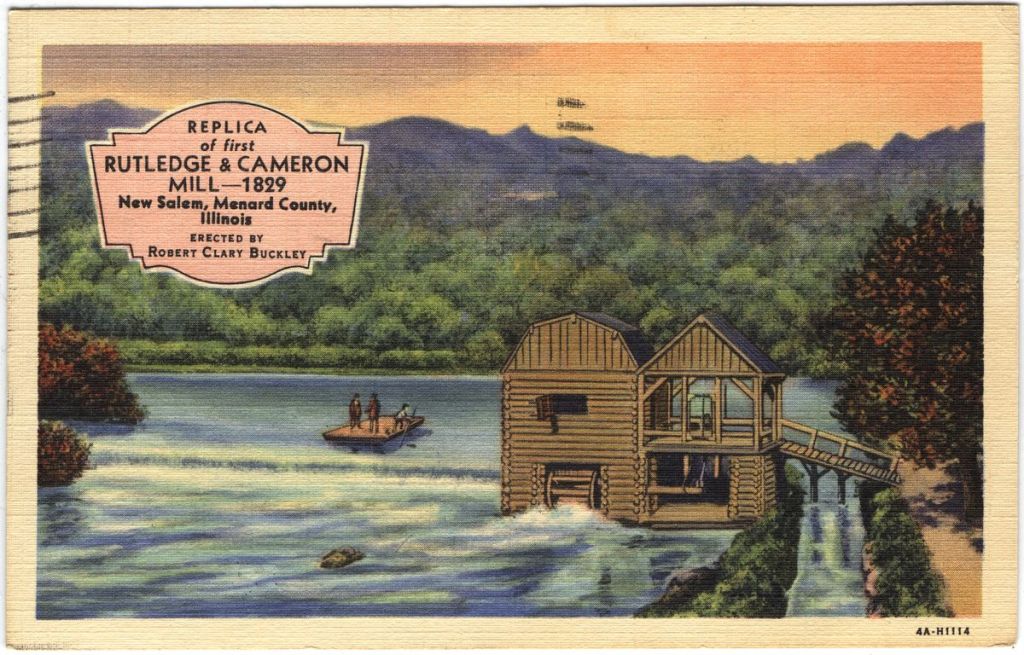

The place that I longed to see most was the final resting place of Abraham Lincoln’s first love, Ann Mayes Rutledge. She was born on January 7, 1813, near Henderson, Kentucky, the third of ten children born to Mary Ann Miller Rutledge and James Rutledge. In 1829, her father moved to Illinois and became one of the founders of New Salem, a community located 21 miles northwest of Springfield.

James Rutledge built a dam, sawmill, and gristmill in New Salem and is credited with laying out the town and selling the first lots of land there. In time, he converted his home into a tavern and inn where Ann worked — eventually, she took over the family business. Allegedly, Ann was the first (some say the only) girl to attend New Salem School. She was described as physically beautiful, 5 feet, 3 inches tall, 120 pounds with auburn hair, blue eyes, and a fair complexion. Her attitude was always positive, described as sweet and angelic, beloved by all who knew her. Her schoolteacher, Mentor Graham, described her as beautiful, amiable, kind, and an exceptionally good scholar. In 1832, young Abraham Lincoln boarded at the Rutledge Inn, where he got to know her.

While historians may disagree on the depth of her relationship with the rail splitter, there is no doubt that Ann Rutledge knew Abraham Lincoln. Ann died before the invention of photography, so no photos of her exist and no contemporary drawings of her have ever been found. Little in the way of verifiable data survives about Ann. Most of the details of her life were collected by Lincoln’s law partner of 17 years, former Springfield Mayor William Herndon. Billy was among the first to research those early years of Lincoln. While researching his book on Lincoln, Herndon retraced Lincoln’s tracks through central Illinois and southern Indiana. Billy Herndon did not care for Mary Lincoln and the feeling was mutual. So it comes as no surprise that Herndon was the first to push the relationship between Abraham and Ann.

Herndon’s details about Ann’s life came from people that knew Ann in New Salem, witnesses that historians have called “Herndon’s informants.” Rutledge neighbor James Short described Ann as “a good-looking, smart, lively girl, a good housekeeper, with a moderate education.” Likewise, Harvey Lee Ross, a boarder at the Rutledge family tavern in New Salem described Ann as “very handsome and attractive, as well as industrious and sweet-spirited. I seldom saw her when she was not engaged in some occupation – knitting, sewing, waiting on tables, etc…I think she did the sewing for the entire family. Lincoln was boarding at the tavern and fell deeply in love with Ann, and she was no less in love with him. They were engaged to be married, but they had been putting off the wedding for a while, as he wanted to accumulate a little more property and she wanted to go longer to school.” When interviewed by Herndon, Ann’s family testified that Lincoln was certainly smitten with Ann.

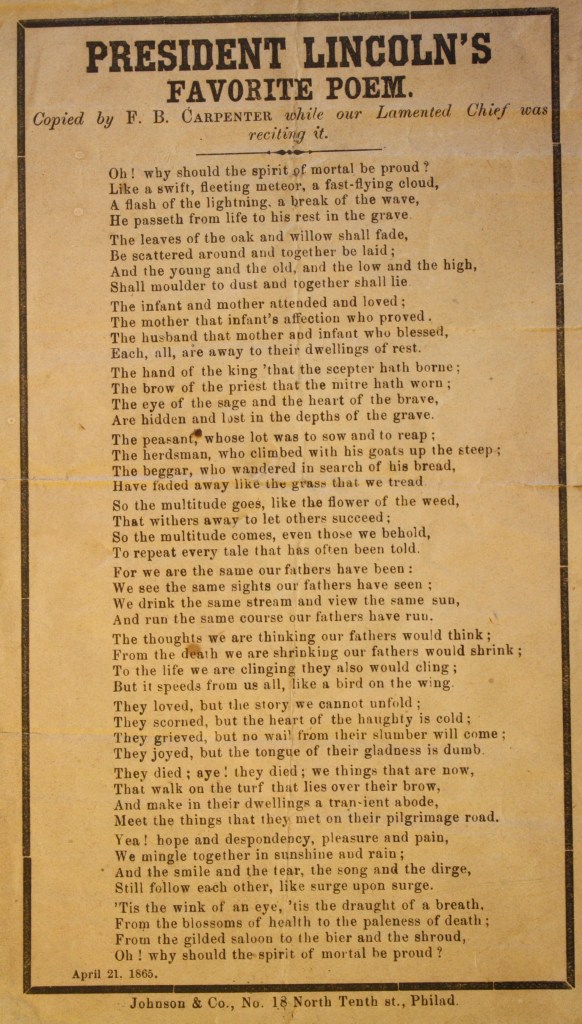

Not only was Lincoln attracted to Ann’s good looks, but he was also intrigued by her intelligence, a rare quality on the frontier. Herndon once said “I believe his very soul was wrapped up in that lovely girl. It was his first love – the holiest thing in life – the love that cannot die.” That all changed on August 25, 1835, when typhoid fever swept through New Salem and 22-year-old Ann Rutledge died. Legend states that Ann called Lincoln to her deathbed for a final goodbye before passing. Ann’s death unhinged Lincoln, leaving him severely depressed, a condition he would battle for the rest of his life. Upon her death, Lincoln confided to Mentor Graham that he felt like committing suicide, but Graham reassured him that “God has another purpose for you.” New Salem resident John Hill later said “Lincoln bore up under it very well until some days afterward when a heavy rain fell, which unnerved him.” Lincoln’s friend, Henry McHenry, testified that after Ann’s passing Lincoln “seemed quite changed, he seemed retired, & loved solitude, he seemed wrapped in profound thought, indifferent, to transpiring events.”

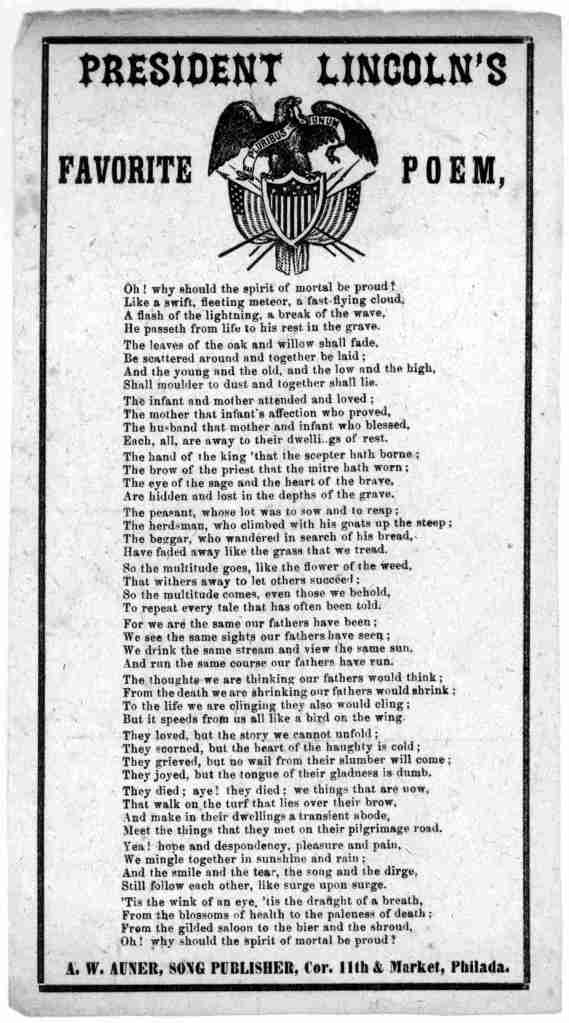

According to author Harvey Lee Ross in his book The Early Pioneers and Pioneer Events of the State of Illinois, Lincoln told friends: ‘My heart is buried in the grave with that dear girl. He would often go and sit by her grave and read a little pocket Testament he carried with him.” Another New Salem neighbor, Isaac Cogdal told Herndon that President-elect Lincoln confessed his love of Ann to him before leaving Springfield for Washington. “I did really – I ran off the track: it was my first. I loved the woman dearly & sacredly: she was a handsome girl – would have made a good loving wife – was natural and quite intellectual, though not highly educated…I did honestly – & truly love the girl & think often – often of her now.”

Ann was originally buried at the Old Concord graveyard (sometimes called Goodpasture graveyard) a pioneer cemetery located about seven miles northwest of New Salem. Some 200 people were buried there, many of whom knew Abraham and Ann personally. Today they stand as silent sentinels to the truthfulness of their courtship. Lincoln visited her gravesite frequently. According to Herndon, after Ann’s death, Lincoln “sorrowed and grieved, rambled over the hills and through the forests, day and night. He suffered and bore it for a while like a great man — a philosopher. He slept not, he ate not, joyed not. This he did until his body became emaciated and weak, and gave way. In his imagination he muttered words to her he loved … Love, future happiness, death, sorrow, grief, and pure and perfect despair, the want of sleep, the want of food, a cracked and aching heart, and intense thought, soon worked a partial wreck of body and of mind.”

To friends, Lincoln claimed that the thought of “the snows and rains fall(ing) upon her grave filled him with indescribable grief.” For days following her death, damp, stormy days, and gloomy weather triggered a deep depression that sent Lincoln to her gravesite where he lay prostrate over Ann’s grave. Lincoln’s behavior became so alarming that his friends sent him to the house of another kind friend, Bowlin Greene, who lived in a secluded spot hidden by the hills, a mile south of town. According to Herndon, “Here Lincoln remained for weeks under the care and ever-watchful eye of this noble friend, who gradually brought him back to reason or at least a realization of his true condition.” Yes, Abraham Lincoln knew Old Concord Graveyard well.

Here’s where the story takes a strange turn. Many years later, some enterprising citizens of nearby Petersburg, a town located four miles to the north, decided that Ann’s grave could help put their town on the map. Chief among them was Petersburg undertaker Samual Montgomery, ironically an elderly relative of Ann’s, and a cemetery promoter with the improbable name of D.M. Bone. These ad-hoc graverobbers decided it would be financially advantageous to move Rutledge’s remains for fear that their cemetery needed the draw of a famous name to compete with crosstown rival Rose Cemetery.

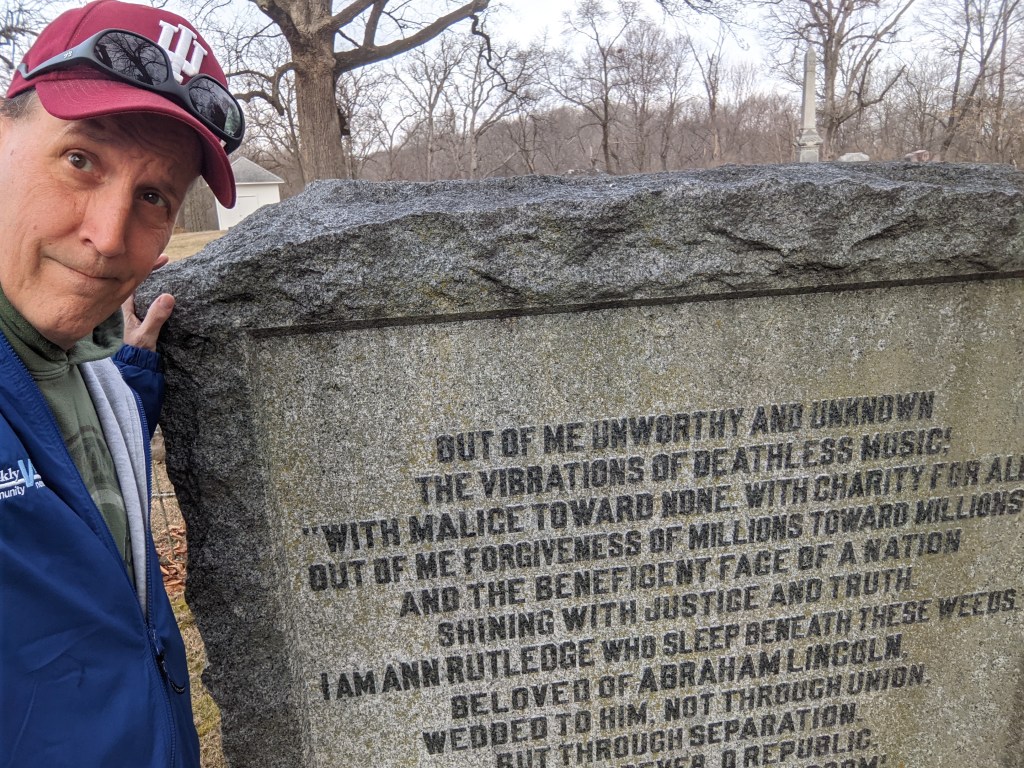

For three decades, all that marked Ann’s grave at the new cemetery was a rough stone with her name emblazoned in white letters on the front. In January 1921, Rutledge’s grave was fitted out with a magnificent granite monument inscribed with the text of the poem “Anne Rutledge,” from Edgar Lee Masters’s Spoon River Anthology. His words, engraved on her cenotaph at Oakland Cemetery are haunting: “I am Ann Rutledge who sleeps beneath these weeds, Beloved in life of Abraham Lincoln, Wedded to him, not through union, But through separation. Bloom forever, O Republic, From the dust of my bosom!” Regardless of the attempts by Lincoln biographers like Herndon, Ward Hill Lamon (Lincoln’s bodyguard), Carl Sandburg, and Indiana Senator Albert Beveridge to legitimize the Lincoln/Rutledge romance as fact, by the 1930-40s, Lincoln scholars expressed increased skepticism of the story. Most biographers agree that Lincoln and Rutledge were close, but several historians point to a lack of evidence of a love affair between them.

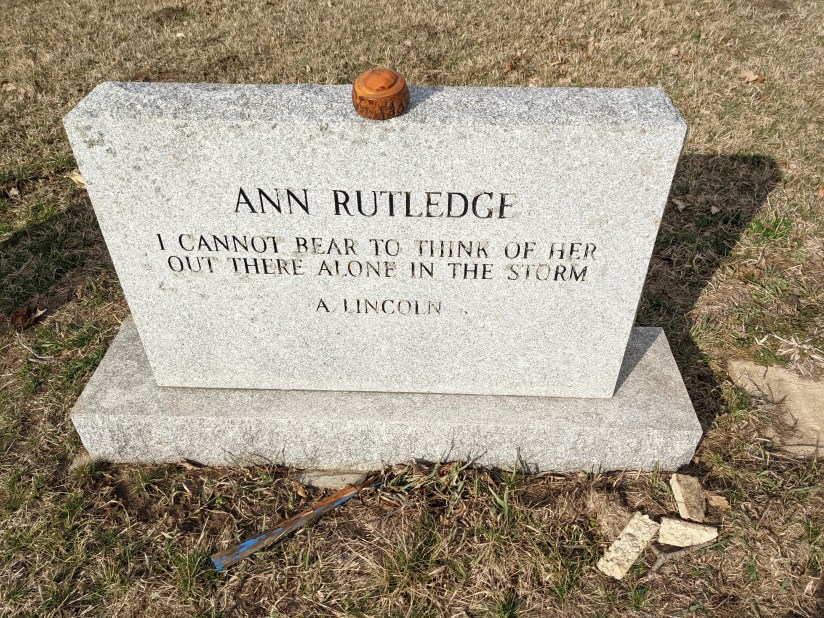

For my part, as a lifelong student of Lincoln, I choose it to be true. It is for that reason that I traveled to Petersburg, Illinois in search of Ann Rutledge’s grave. Finding Oakland Cemetery is an easy task and worth the visit. The massive granite marker is the most impressive memorial in the graveyard. Surrounded by an equally impressive wrought iron fence, the rough stone marker that originally graced her final resting place remains tucked away at the front of the plot although her name is slowly eroding away. Edgar Lee Masters’ epitaph is clear, legible, and easy to read. Master’s grave is only yards away. As impressive as the site may be, if you know the backstory, an overpowering soullessness pervades the spot simply because she is not there.

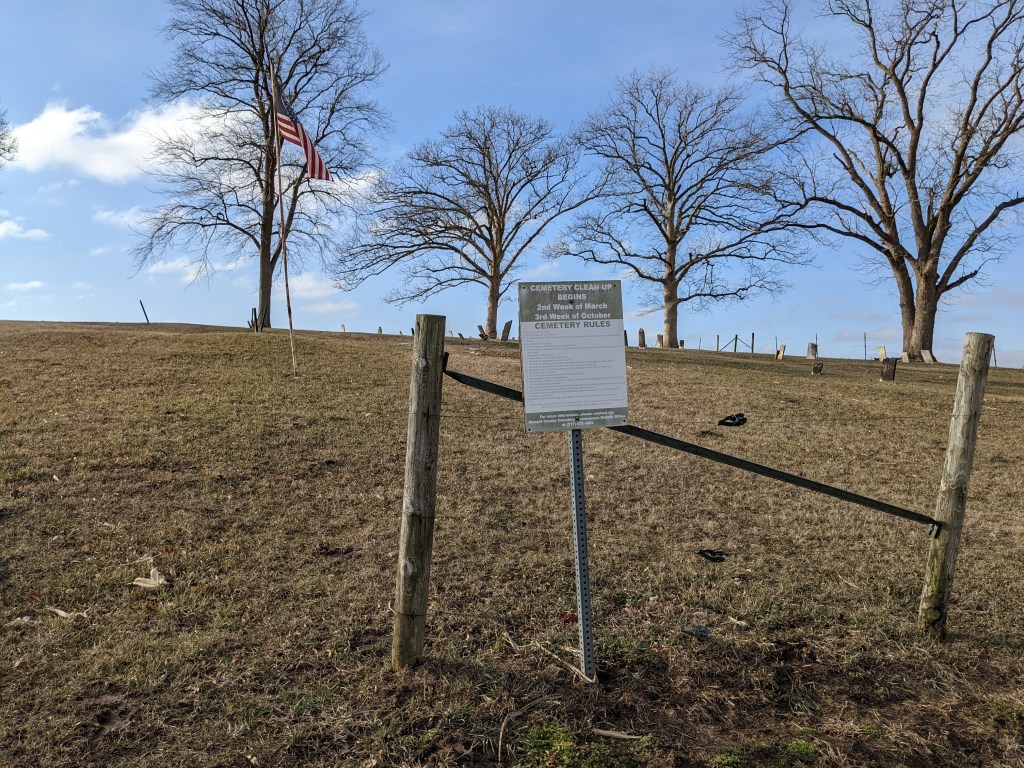

The place I really wanted to find was the Old Concord Graveyard. So I did what every stranger in a strange place does: I consulted Google maps. Oh, the navigator took me there, but just barely. The map directions led me to Route 97 North and the Lincoln Trail Road through the farm fields of Menard County, off the paved highway, and onto a gravel road. Like most midwestern roads, the winding serpentine roadways mimic the buffalo traces of centuries past. They wind through hills cut not by machinery, but by carts pulled by oxen and horses generations ago. Blind hills make the driver wonder if the road continues past each rise and dangerous curves make you tighten your grip on the steering wheel. Along the way, pheasants and quail stroll leisurely along the roadside. This is their domain and they fear no man out here.

Time and time again, my GPS ended in front of a brick farmhouse proclaiming “You have reached your destination.” This was not a cemetery, so I retraced my route, and five miles later, I found myself in the same spot. Finally, I pulled into the driveway and knocked on the door. My summons was answered by a friendly dog followed by a lovely mature woman. I threw myself upon the mercy of a stranger, apologized for the intrusion, and asked if this was the place. She smiled and said, “Well, you’re close” and led me to the side of the house where she pointed to the cemetery about a half mile in the distance.

She told me to head back out on the county road and keep turning left until I found an abandoned, dried-up waterway through a pair of cornfields. She said, “It is not really a road but the county crews still drive their equipment back there to keep the grass cut, so you should be able to find it,” The cemetery can not be seen from the gravel road, so it took me two passes to find it. When I did, I nervously went offroading about a quarter mile back upon a grassy lane between two cornfields. It had been raining before my arrival and rain was predicted for later that day, so I was less than confident that I could make it without getting stuck. Luckily, I arrived there safely.

The ancient graveyard is filled with veterans of the Revolutionary War like Robert Armstrong from North Carolina who died September 9th, 1834. Next to Robert is the marker of his son, Jack Armstrong of the Clary Grove gang, who famously fought Abe Lincoln to a draw in a wrestling match in New Salem. The battle became the stuff of legend and ultimately got Lincoln inducted into the Wrestling Hall of Fame. It did nothing for Jack Armstrong though. He died in 1854 although his stone incorrectly lists the death date as 1857. Most of the stones have been laid down face up so that they may still be read. Many are broken and rest in pieces strewn about in this ancient burying ground. A flagpole stands guard with a tattered American flag that shows the scars of a constant battle with the rough winds of the Illinois plains.

Ann’s grave rests on top of the hill next to that of her father, whose body was not removed to the new cemetery. Also near Ann is the grave of her brother David who died in 1842, a decade after serving with Abraham Lincoln in the Black Hawk War. There are many Rutledges still resting here. It is likely that most, if not all of them, were known by Ann or she by them. From Ann’s grave, I could look over my shoulder and see the farmhouse where I started. I wonder to myself what it would be like to live so close to such a magical place. Talking with the lady she told me they had been living there for 30 years. They had directed a few travelers like me to the spot, but not many. She informed me that her home was built by the Grosbaugh family and that it would have been there in 1835 when Ann drew Lincoln there. She pointed to an ancient natural stone step in the sideyard between her house and the graveyard and stated, “This was the watering trough and buggy turnaround, the start of a path that used to lead directly to the cemetery. It hasn’t been used in over a century.”

I’ve chased Lincoln all over this country. I’m sure I have stepped in his footprints many times. This spot, the Old Concord Cemetery, is the toughest Lincoln site I have ever found. It is impossible to find on your own and no map will lead you here. Here young Abraham Lincoln came day after day to mourn over his lost love. Here he lay upon her grave from autumn to winter, protecting her because he could not bear the thought of it raining or snowing upon her mortal remains. Today, a modern stone rests in Old Concord Graveyard on the spot that reads: “Original Grave of Ann Mayes Rutledge Jan. 7, 1813-August 25, 1835. Where Lincoln Wept.” Lincoln was here and here Ann remains. Her body literally melted into the soil of the central Illinois prairie. Here is the lone individual spot where anyone may visit to experience the raw emotion that was Abraham Lincoln.