Original publish date: September 23, 2021. https://weeklyview.net/2021/09/23/the-devils-tower/

https://www.digitalindy.org/digital/collection/twv/id/4308/rec/153

Over the last couple of weeks, I detailed a long-lost Indiana landmark known as the Hoosier Slide in Michigan City. This giant mound of sand became a tourist attraction when visitors discovered that they could slide down its slopes on slices of cardboard or fragments of cloth like a sled on a snow mound. The Hoosier Slide disappeared from the northern Indiana landscape around World War I after it was purchased by the Ball Brothers Corporation in Muncie to furnish the distinctive blue tint for their popular Ball Brand fruit jars.

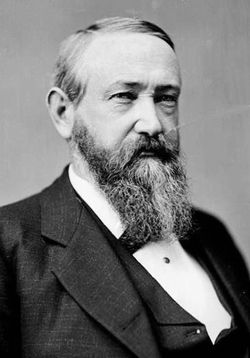

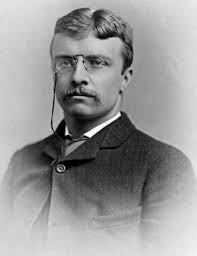

Continuing that theme, it was 115 years ago this week (Sept. 24, 1906) that President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed Devils Tower in Wyoming as the nation’s first National Monument, under new authority granted to him by Congress in the Antiquities Act. The Antiquities Act resulted from concerns about protecting mostly prehistoric Native American ruins and artifacts (aka “antiquities”) located on federal lands. The United States Congress designated the area a U.S. forest reserve in 1892. However, in the ensuing years, the threat of commercial development and the removal of artifacts from these unprotected lands by private collectors, whom Teddy famously referred to as “pot hunters,” had become a serious problem. Making this a high-priority goal for Teddy’s second term.

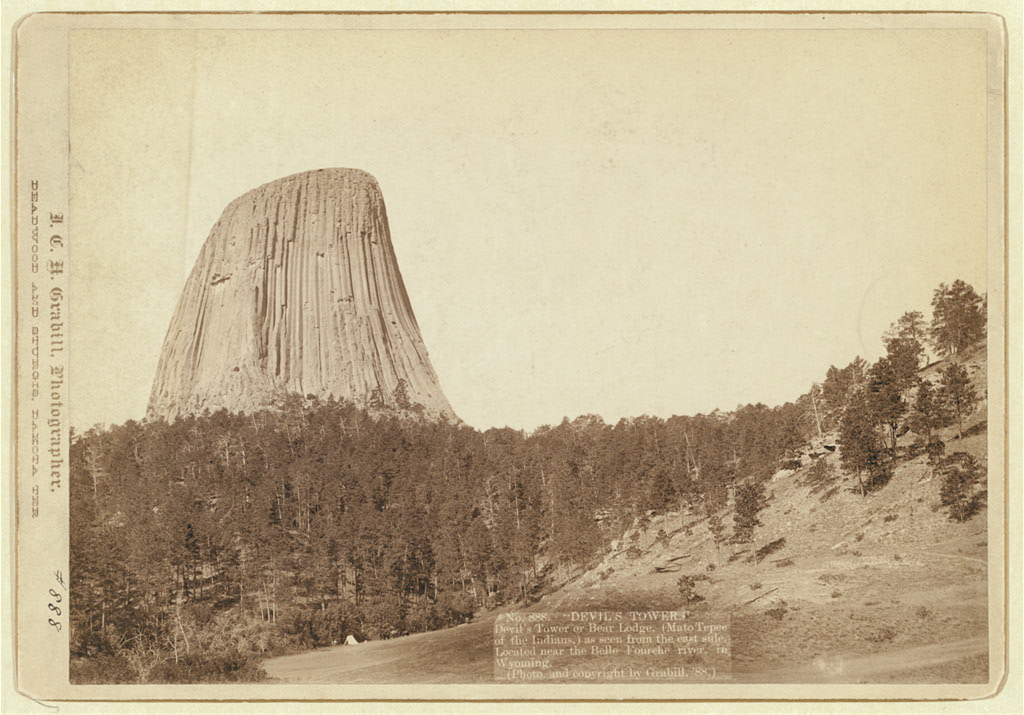

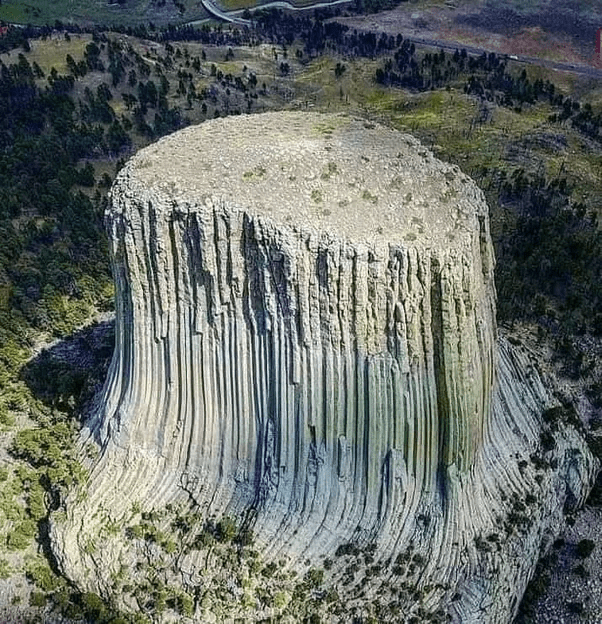

Although Devils Tower (apostrophe purposely omitted) might not ring any bells in your house, it was so important to Roosevelt that he designated it for protection before he established the Grand Canyon Game Preserve by proclamation on November 28, 1906, and the Grand Canyon National Monument on January 11, 1908. Devils Tower, also called Bear Lodge Butte, is part of the Black Hills mountain range located above the Belle Fourche River near Hulett and Sundance in Crook County, northeastern Wyoming. The tower, technically called a “monolith”, was formed from cooled magma exposed through erosion. It stands 1,267 feet tall; 867 feet from summit to base (5,112 feet above sea level) and encloses an area of 1,347 acres.

The oldest rocks visible in Devils Tower National Monument were once part of a shallow sea during the Triassic period 250 million years ago, which saw the rise of reptiles and the first dinosaurs. Devils Tower hails from the Jurassic period, about 200 million years ago, which ushered in birds and mammals. The Tower was here 150 million years before the Rocky Mountains and the Black Hills were formed. It is easy to imagine that the thought of dinosaurs roaming around Devils Tower may well have sparked Teddy Roosevelt’s vivid imagination, thus leading him to designate it as the country’s first National Landmark.

Fur trappers may have visited Devils Tower, but they left no written evidence of having done so. The first documented Caucasian visitors were members of Captain William F. Raynolds’s 1859 expedition to Yellowstone. Sixteen years later, Colonel Richard I. Dodge escorted a US Government Office of Indian Affairs scientific survey party to the massive rock formation and coined the name Devils Tower. The misnomer was created when his interpreter reportedly misinterpreted a native name to mean “Bad God’s Tower”. The Indigenous Native American people had many names for the outcropping including Bear’s House, Grizzly Bear Lodge, Bear’s Tipi, Home of the Bear, Bear’s Lair, Tree Rock, Great Gray Horn, and Brown Buffalo Horn.

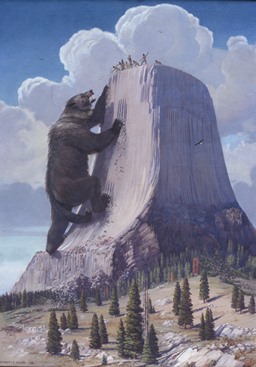

According to the lore of the Lakota tribe, the traditional name for the tower came after a group of girls went out to play and were spotted by several giant bears, who began to chase them. In an effort to escape the bears, the girls climbed atop a rock, fell to their knees, and prayed to the Great Spirit to save them. Hearing their prayers, the Great Spirit made the rock rise from the ground towards the heavens so that the bears could not reach the girls. The bears, in an effort to climb the rock, left deep claw marks in the sides, which had become too steep to climb. Those are the marks that appear today on the sides of Devils Tower. When the girls reached the sky, they were turned into the star formation known as the “Seven Sisters.”

Another version tells that two Kiowa Sioux boys wandered far from their village when Mato the bear, a huge creature that had claws the size of teepee poles, spotted them and wanted to eat them for breakfast. He was almost upon them when the boys prayed to Wakan Tanka the Creator to help them. They rose up on a huge rock, while Mato tried to get up from every side, leaving huge scratch marks as he did. Finally, he sauntered off, disappointed, discouraged, and hungry. The bear came to rest east of the Black Hills at what is now Bear Butte. Wanblee, the eagle, helped the boys off the rock and back to their village. A painting depicting this legend by artist Herbert A. Collins hangs over the fireplace in the visitor’s center at Devils Tower.

In a Cheyenne version of the story, the giant bear pursues the girls and kills most of them. Two sisters escape back to their home with the bear still tracking them. They tell two boys that the bear can only be killed with an arrow shot through the underside of its foot. The boys have the sisters lead the bear to Devils Tower and trick it into thinking they have climbed the rock. The boys attempt to shoot the bear through the foot while it repeatedly attempts to climb up and slides back down leaving more claw marks each time. The bear was finally scared off when an arrow came very close to its left foot. This last arrow continued to go up and never came down.

Wooden Leg, a Northern Cheyenne, related still another legend told to him by an old man as they were traveling together past the Devils Tower around 1866. A Native American man decided to sleep at the base of Bear Lodge. In the morning he found that he had been transported to the top of the rock by the Great Medicine with no way down. He spent another day and night on the rock with no food or water. After he had prayed all day and then gone to sleep, he awoke to find that the Great Medicine had brought him back down to the ground. Devils Tower is still considered to be sacred ground which has caused distress among the Native American tribes who described the Devils Tower designation as offensive. However, the name was never changed.

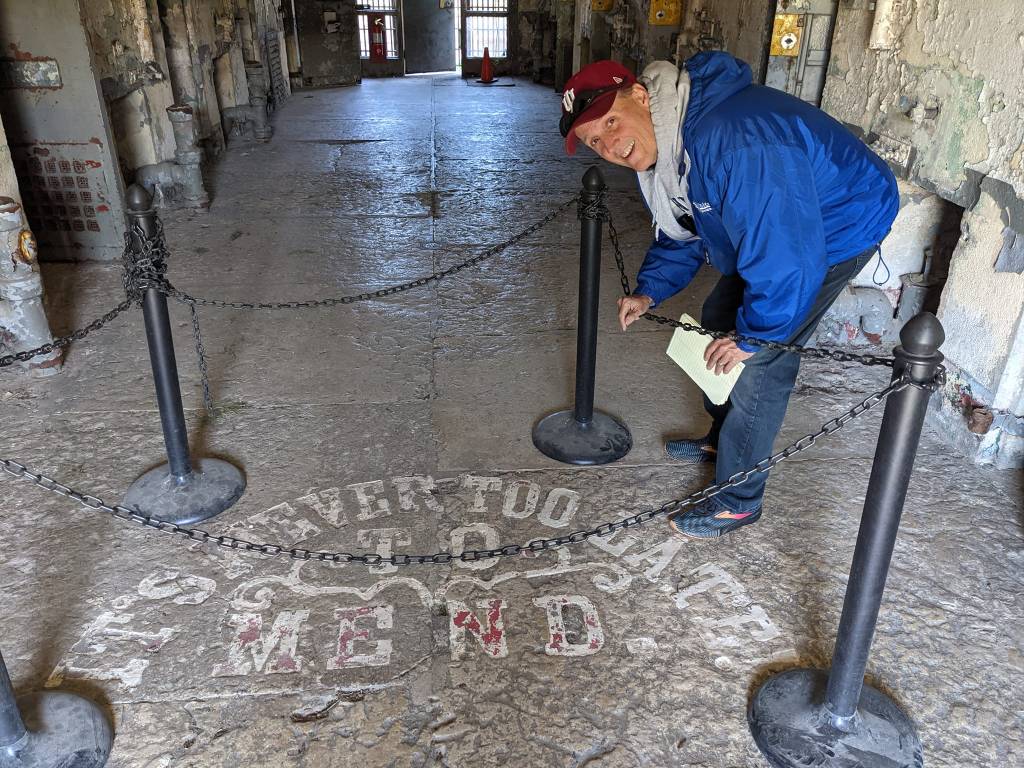

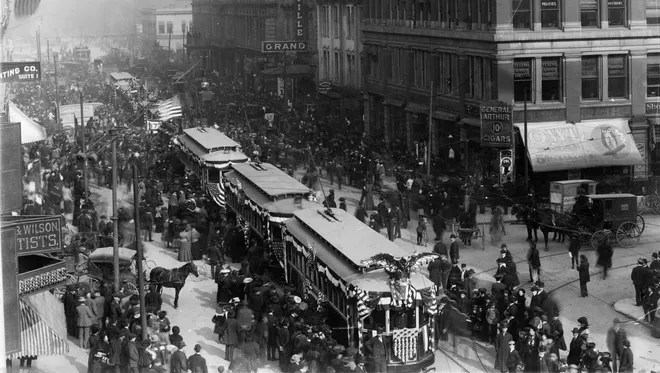

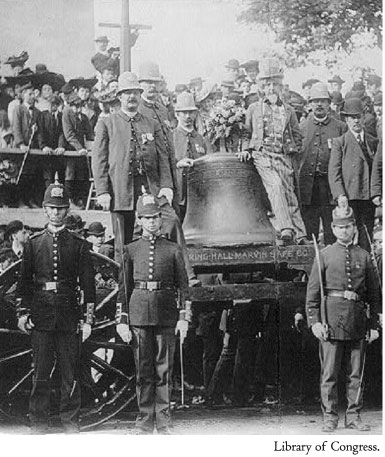

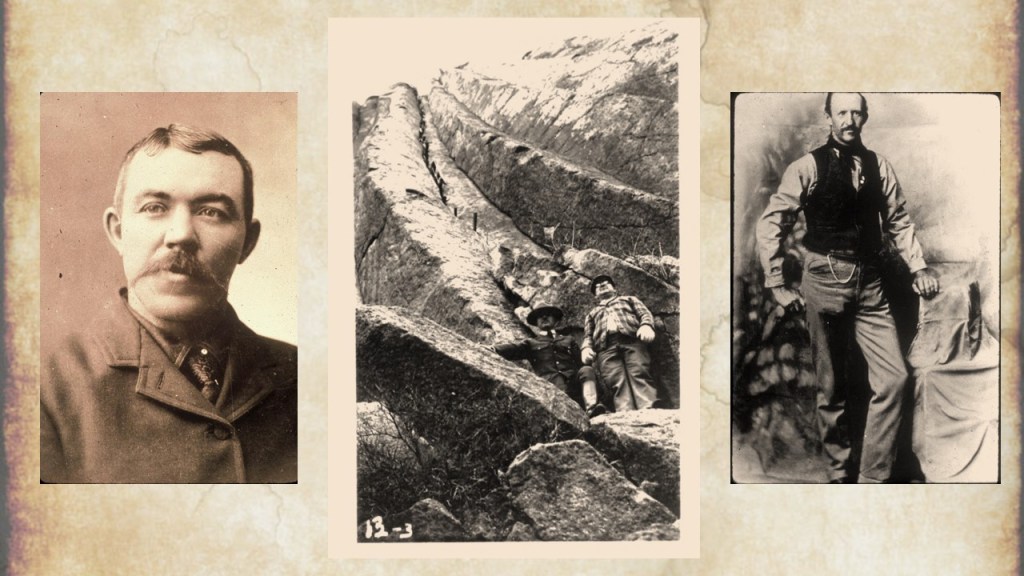

In recent years, climbing Devils Tower is on many a bucket list. The first known ascent of Devils Tower occurred on July 4, 1893. It is credited to a pair of local ranchers, William Rogers and Willard Ripley. They completed this first ascent after constructing a ladder of wooden pegs driven into cracks in the rock face. About 1,000 people came from up to 12 miles away to witness this first formal ascent of the tower. Rogers’ wife Linnie ascended the ladder two years later, becoming the first woman to reach the summit of the tower. An estimated 215 people later ascended the tower using Rogers’ ladder. It was last used in 1927 by stunt climber Babe (”the Human Fly”) White, a roaring twenties daredevil who climbed skyscrapers all over the country for publicity.

Rogers and Ripley’s climb jump-started a sport climbing industry at the tower that continues to the present day. Over thirty years, the ladder, located on the southeast side of Devils Tower, fell into disrepair. Today, what remains of the ladder begins about 100 feet above the ground and ascends from there to the summit. Sources vary on the original length of the ladder, some accounts say it was 350 feet while others say 270 feet. In the 1930s, the decision was made to remove the lower 100 feet of the ladder for safety reasons. The ladder can still be seen from the trails around the monument.

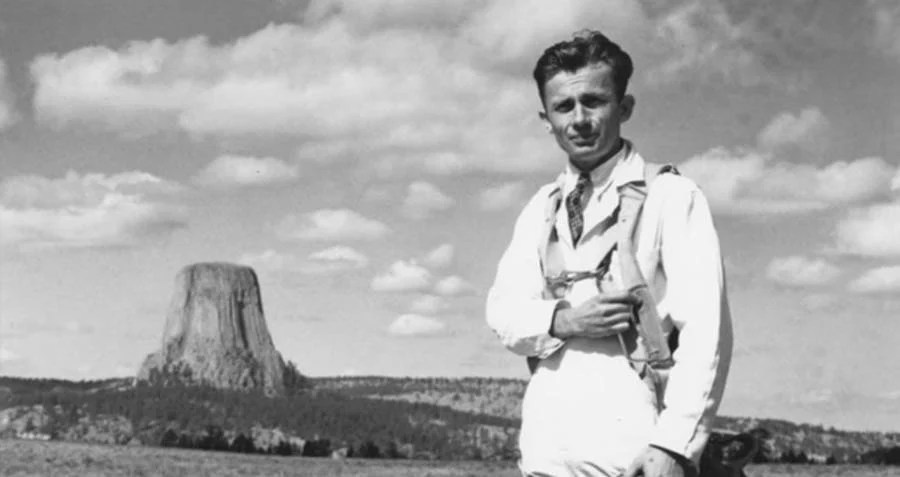

In 1941, Devils Tower became front-page news. Daredevil George Hopkins parachuted onto Devils Tower to settle a bet. His intention was to repel down the slope via a 1,000-foot rope dropped to him after a successful landing on the butte. To Hopkins’ horror, the package containing the rope, a sledgehammer, and a car axle to be driven into the rock as an anchor piton for the rope. As the weather deteriorated, a second attempt was made to drop equipment, but the rope froze in the rain and wind and could not be used. Hopkins was stranded for six days, exposed to frigid temperatures, freezing rain, and 50 mph winds before a mountain rescue team reached him and brought him down.

Today, hundreds of climbers scale the sheer rock walls of Devils Tower via climbing routes covering every side of the prehistoric landmark. All of them must check in with a park ranger before and after attempting a climb. No overnight camping at the summit is allowed; climbers return to base on the same day they ascend. Because the Tower is sacred to several Plains tribes, including the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Kiowa, many Native American leaders objected to climbers ascending the monument, considering this to be a desecration. Because of this, a compromise was reached with a voluntary climbing ban during the month of June when the tribes are conducting ceremonies around the monument.

The tower has a flat top covering 1.5 acres and its fluted sides give it an otherworldly appearance. Its color is mainly light gray and buff. Lichens cover parts of the tower, and sage, moss, and grass grow on its top. Chipmunks and birds live on the summit, and a pine forest covers the surrounding countrysides below. Additionally, Devils Tower National Monument protects many species of wildlife, such as white-tailed deer, bald eagles, and prairie dogs, the latter of which maintain a sizeable population at the base of the monument.

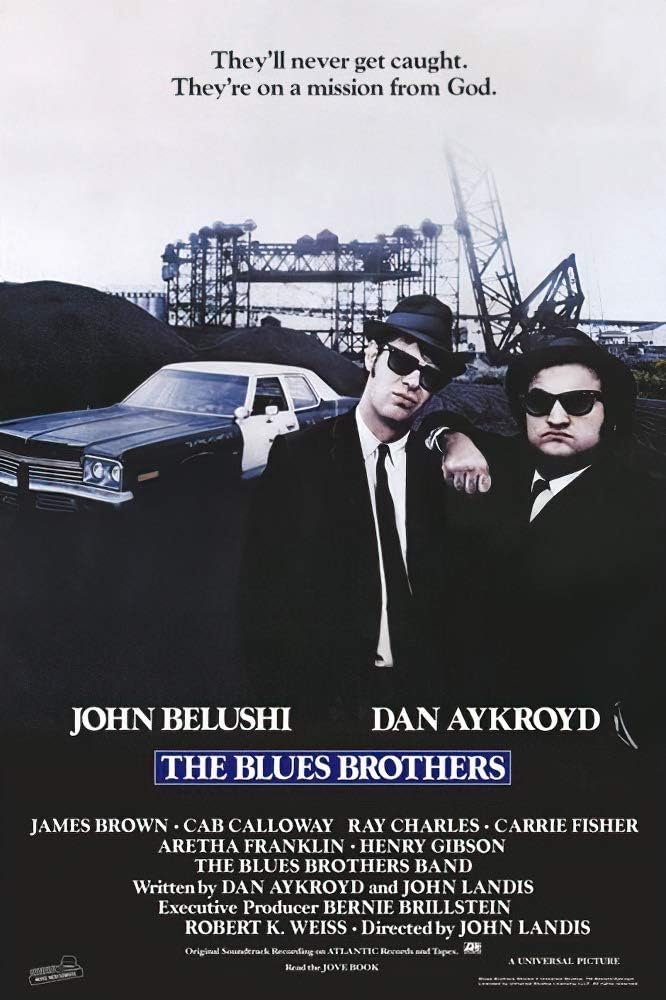

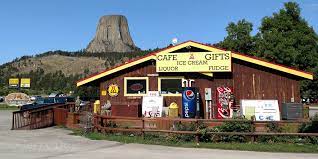

All of this is well and good and obviously, had the Hoosier slide been likewise protected, we may still be sliding down the massive sand dune in northern Indiana today. But movie buffs everywhere recognize Devils Tower for another reason. The 1977 movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind used the formation as the bellwether of its climactic scene. It soon became the film’s trademark logo. Its release caused a large increase in visitors and climbers to the monument. Today, the otherworldly pull and Hollywood fame of Devils Tower has made it a cultural waymark.

With the funds from the film’s creation, the owners of the surrounding land were able to open a campground and restaurant to host climbers, sightseeing fans of the landscape, and movie buffs. Campers are welcome to hike and climb the tower twenty-four hours a day, and at night they’re treated to a showing of Close Encounters on a screen at the base of the landmark. According to the brochure, “Visitors leave with a new appreciation for the unique rock formation and a deepened curiosity about our place in space.”

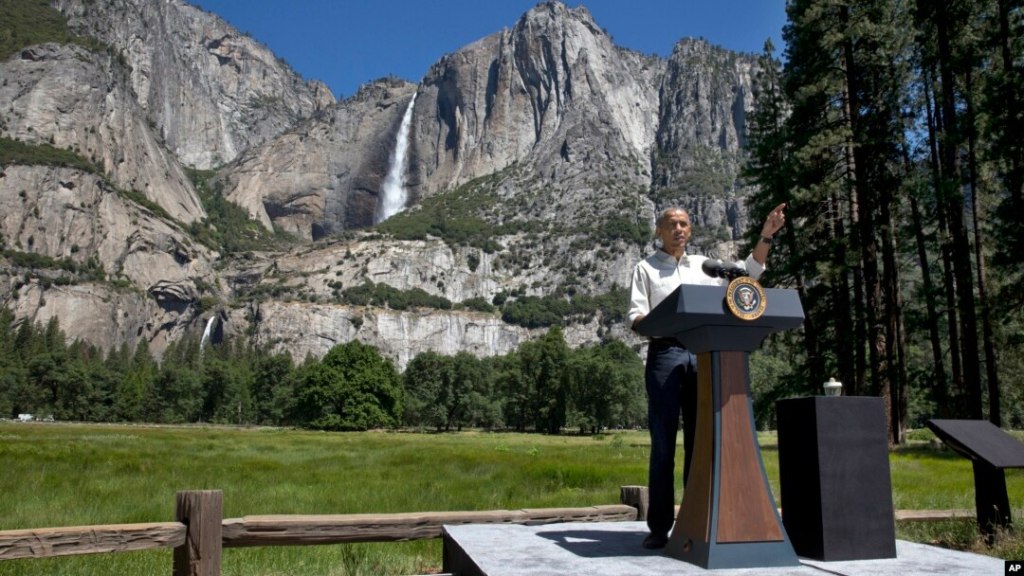

And, for an added “new appreciation”, although Teddy Roosevelt is considered to be the “father” of the National Park System, you might be interested to learn that during his two terms, President Obama established more monuments than any President before him with 26, breaking the previous record held by President Theodore Roosevelt who had 18. In short, on both accounts, it was a bi-partisan land grab for the good.