Original publish date October 7, 2021.

https://weeklyview.net/2021/10/07/the-monster-mash-gets-banned/

https://www.digitalindy.org/digital/collection/twv/id/3927/rec/246

Quick, what do Bing Crosby, David Bowie, Elvis Presley, The Beatles, Frank Sinatra, The Wizard of Oz, ABBA, Queen, The Everly Brothers, Johnny Cash, The Rolling Stones, The Sex Pistols, Donna Summer, Perry Como, Bob Dylan, Glenn Miller, The Kinks, The Who, Louis Prima, Liberace, Ella Fitzgerald, and “The Monster Mash” have in common? At one point or another, all of these artists, or one of their songs, have been banned by BBC radio.

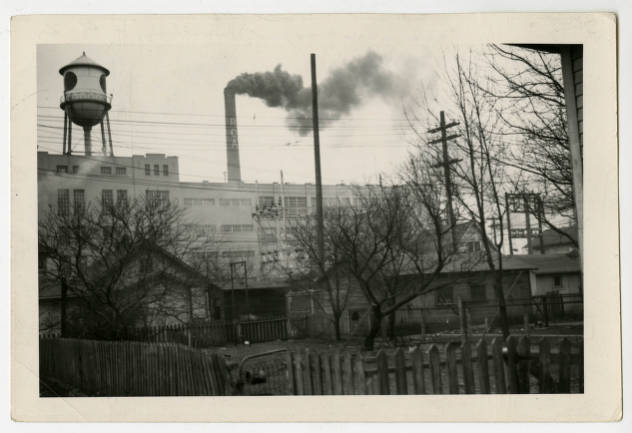

Looking at that list, some are no-brainers, others are head-scratchers. Reasons for bans range from the very British reasons of “lyrics are too tragic” (Everly Brothers “Ebony Eyes”) to “connotations with armies and fighting” (ABBA’s “Waterloo” during the Gulf War). David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” was banned until AFTER the Apollo 11 crew landed and safely returned. Paul McCartney & Wings song “Give Ireland Back to the Irish” is not a hard one to figure out but how about Bing Crosby’s “Deep in the Heart of Texas”? In 1942, the BBC banned the song during working hours on the grounds that its infectious melody might cause wartime factory workers to neglect their tools while they clapped along with the song. Oh, those proper Brits.

Some bans are humorous and fairly obvious. Louis Prima’s 1945 World War II song “Please No Squeeza Da Banana” (admit it, you giggled) was specifically sent out by the New Orleans jazz great to the GI’s returning home from World War II. And the Wizard of Oz film’s “Ding Dong the Witch is Dead” was banned after the death of Margaret Thatcher 74 years after the movie debuted (it still made it to # 2 on the British charts).

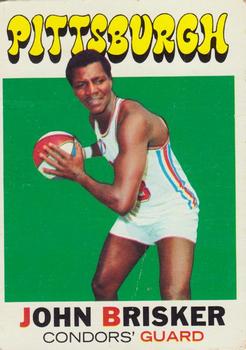

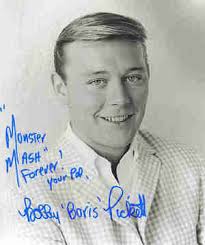

But the REAL head-scratcher this time of year? This Saturday marks 59 years since Bobby Pickett’s “Monster Mash” was banned by the BBC. On October 20, 1962, the BBC claimed the song was “too morbid” for airplay. The traditional autumnal anthem was released in August of 1962 during the height of summer but cemented its place in music history when it reached number one on the U.S. charts just in time for Halloween of that year.

The song is narrated by a mad scientist whose monster creation rises from his slab to perform a new dance routine. The dance soon becomes “the hit of the land,” and the scientist throws a party for other monsters, including the Wolfman, Igor, Count Dracula, and a pack of zombies. The mad scientist explains that the twist has been replaced by the Monster Mash, which Dracula embraces by joining the house band, the Crypt-Kicker Five. The story closes with the mad scientist inviting “you, the living” to the party at his castle. The song used primitive, yet effective, sound effects: pulling a rusty nail out of a board to simulate a coffin opening, blowing water through a straw to mimic a bubbling cauldron, and chains dropped onto a tile floor to ape the monster’s movements.

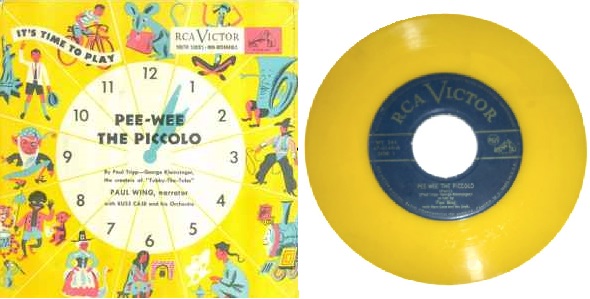

Bobby Pickett and Leonard Capizzi wrote the anthem and, as the song notes, recorded it with the “Crypt Kicker Five” consisting of producer Gary Paxton, Johnny MacRae, Rickie Page, Terry Ber, and pianist Leon Russell. Yes, THAT Leon Russell. The Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Famer was famously late for the session. And the backup singers on the original single? They were led by none other than Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Famer Darlene Love (“He’s a Rebel”). Mel Taylor, drummer for the Ventures, is sometimes credited with playing on the record as well.

The song came about quite by accident. Bobby Pickett, a Korean War vet, and aspiring actor was fronting a band called the Cordials at night and going to auditions during the day. One night, on some long-forgotten nightclub stage with his band, Pickett ad-libbed a monologue in the distinctive lisping voice of horror movie star Boris Karloff while performing the Diamonds’ “Little Darlin’.” Karloff, the distinctive British actor perhaps best remembered for voicing the Grinch, conquered a childhood stutter but never lost his idiomatic lisp.

The audience loved it, and the band encouraged Pickett to do more with the Karloff imitation. It wasn’t long before Bobby changed his name to “Boris” and a Halloween icon was born. In the song, Pickett not only imitates Boris Karloff but also Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula complaining “Whatever happened to my Transylvania Twist?” and actor Peter Lorre as Igor, despite the fact that Lorre never played that character on screen. Every major record label declined the song, but after hearing it, Crypt Kicker Fiver member Gary S. Paxton agreed to produce and engineer it on his Garpax Records label. The single sold a million copies, reaching number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart for two weeks before Halloween in 1962 (it remained on the U.S. charts for 14 weeks).

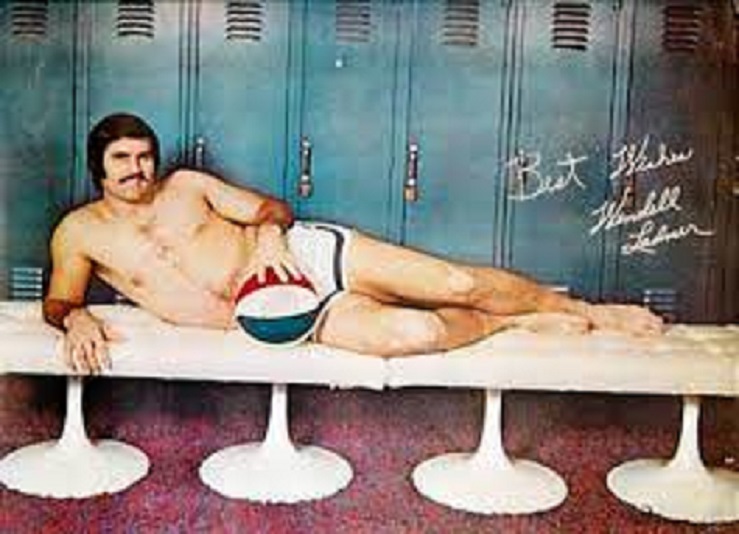

The song cemented its generational appeal when it re-entered the U.S. charts twice, in August 1970, and again in May 1973 when it peaked at #10. The UK ban was reversed in 1973, 11 years after the song was released. In October of that year, it officially became a British “graveyard smash” when it charted at number three in the UK. For the second time, the record sold over one million copies. To celebrate the resurgence, Bobby and the Crypt-Kickers toured Dallas and St. Louis around the 1973 Halloween holiday. On this tour, the Crypt-Kickers were composed of Brian Ray, longtime guitarist for Paul McCartney, and folk singer Jean Ray who allegedly was the inspiration for Neil Young’s “Cinnamon Girl.” Pickett frequently toured around the country performing the “Mash,” at one point employing the Brian Wilson-less dry-docked Beach Boys and a very young Eddie Van Halen in his backing band.

Although many listeners were introduced to Pickett’s Monster Mash strictly as a novelty song worthy of Dr. Demento, turns out it was a well-orchestrated musical slot machine whose number hit every decade or so. Pickett tapped in on three distinct national trends colliding simultaneously during those pre-British invasion years. First, the reintroduction of the Universal monster movies at drive-in theatres and on syndicated television. Second, American pop music of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s was populated by novelty songs like “Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polkadot Bikini,” “The Name Game,” “Hello Muddah, Hello Fadduh,” and “The Purple People Eater.” And third, the pop charts were awash with dance songs, from Chubby Checker’s “The Twist” and “Pony Time”, the Orlons “Wah-Wahtusi,” Little Eva’s “Loco-Motion,” to Dee Dee Sharp’s “Mashed Potato Time.”

Pickett’s co-songwriter, Lenny Capizzi, an otherwise mildly successful backup singer, profited from the song right up until he died in 1988. After Pickett landed a recording contract, he remembered his friend Lenny and their brainstorming jams. It had been Capizzi who encouraged Pickett to further utilize his unique impressionist skills in the first place. With the studio album nearly complete, Pickett called Lenny in at the last minute to see if his old pal could jazz up some tracks. But with most of the production money spent, all he could offer Capizzi was second-place songwriter credits. That tiny second-place billing on the single turned out to be the goose that laid the golden egg.

Lenny made a small fortune when “Monster Mash’ charted in 1962. However, it was a payday he spent foolishly on a drug-fueled rock ‘n roll lifestyle. In the early ‘70s, as “Monster Mash” was re-charting, the royalties began rolling in again, this time from both sides of the pond. Alas, within a short time, Lenny was broke again. But every time the song came back — either from airplay in its original version or as a cover (the Beach Boys, Vincent Price, Sha-Na-Na, and many others covered the song) — the royalty checks reappeared. If Pickett hadn’t already spent the original production money by the time Lenny stepped in, Capizzi would have been paid as a one-time session musician and that would have been the end of it. Instead, Lenny stepped in for an afternoon’s work for no money and accepted a co-writer’s credit for a dubious hit. When asked years later about the song, Capizzi couldn’t even recall his contribution.

The song was inspired by Crypt-kicker Five member Gary Paxton’s earlier novelty hit “Alley Oop.” Paxton (1939-2016) built a reputation as an eccentric figure in the 1960s recording industry. Brian Wilson was known to admire his talents and Phil Spector feared him. His creativity and knack for promotion were legendary. In 1965, he produced Tommy Roe’s hit “Sweet Pea.” The next two years, he produced “Along Comes Mary” and “Cherish” both hits for the Association, and followed it up with another for Roe, “Hooray for Hazel.” Paxton moved toward the Bakersfield sound in the late 1960s, concentrating on country music.

Darlene Love, “Monster Mash” backup singer, told Billboard magazine’s Rob LeDonne in 2017, “We had a hard time doing it because it was totally ridiculous. When you do a song like that, you never think you’re going to be famous or that it’ll be a hit. We sat down to listen to the song to try to figure out what the background was going to be. He had to sing his vocals so we could figure out where to come in. It made it more fun, with him singing his line and then us answering him.” For his part, Pickett told The Washington Post, “The song wrote itself in a half hour and it took less than a half-hour to record it.”

On April 25, 2007, Bobby (Boris) Pickett, whose novelty voice talents on “Monster Mash” made him one of pop music’s most enduring one-hit wonders, died in Los Angeles from leukemia at age 69. Pickett was still performing the song live on stage until November 2006, five months before his death. Alongside Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” Pickett’s “Monster Mash,” the song that started out with zero expectations 59 years ago this week, has firmly planted itself as a seasonal standard. And what about the dance? Was there ever a dance created for the song? Well, yes actually, there was. Turns out the Monster Mash is simply a Peanuts-meets-Frankenstein-style stomp-about accented by monster gestures made by outstretched arms and hands. Don’t expect to see that one on Dancing With The Stars any time soon.