Original Publish Date October 2, 2025.

https://weeklyview.net/2025/10/02/immigration-baseball-ptsd-and-the-titanic/

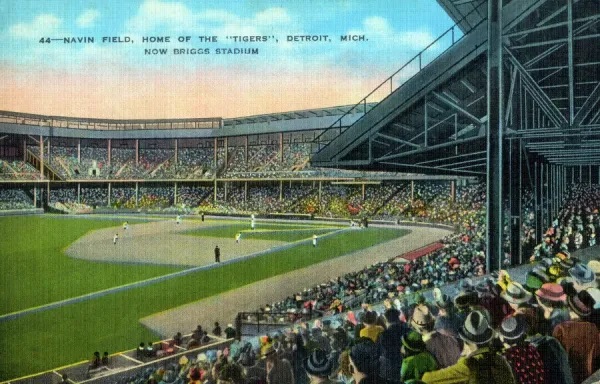

It’s playoff time in Major League Baseball. Right now, there are 12 teams marching toward the World Series. One of those teams, the Detroit Tigers, is heading to the playoffs for the second year in a row following a decade-long drought. The Tigers are one of the most storied franchises in MLB history. Since they became a major league franchise in 1901, the Tigers have won four World Series championships, 11 AL pennants, and four AL Central division championships. From 1912 to 1937, the Tigers played their home games at Navin Field in the Corktown neighborhood of Detroit. Corktown is a traditionally Irish settlement named so because nearly half of its settlers traced their lineage to County Cork, Ireland. Corktown is the oldest neighborhood in Detroit.

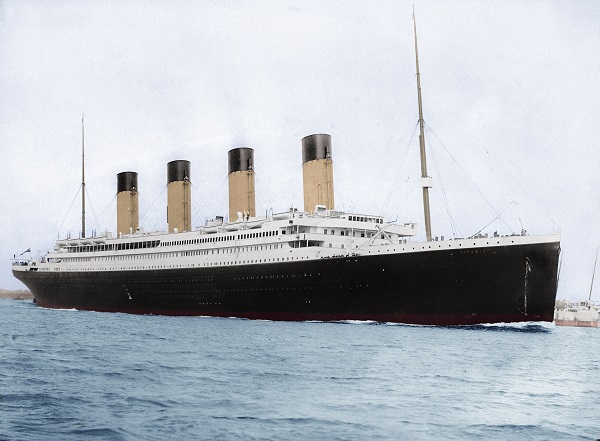

In 1911, the new Tigers owner Frank Navin ordered a new steel-and-concrete baseball park to be built that could seat 23,000 fans. Navin Field opened on April 20, 1912, the same day as the Red Soxs’ Fenway Park in Boston and just 5 days after the RMS Titanic sank. Another ominous portent is the fact that Cleveland Naps player “Shoeless” Joe Jackson scored the first run at Navin Field. Jackson was later banned from baseball as a member of the Chicago “Black Sox” team, accused of throwing the 1919 World Series. The $300,000 price tag for Navin Field translates to about $50 million today. The ballpark featured a 125-foot flagpole in center field that, to this day, is the tallest obstacle ever built in fair territory in a major league park. 26,000 fans crammed into the park for Navin Field’s opening day, postponed two days from its planned inaugural date because of rain. Despite that Motor City milestone, most of the attention was knocked from newspaper headlines the next morning by the sinking of the Titanic.

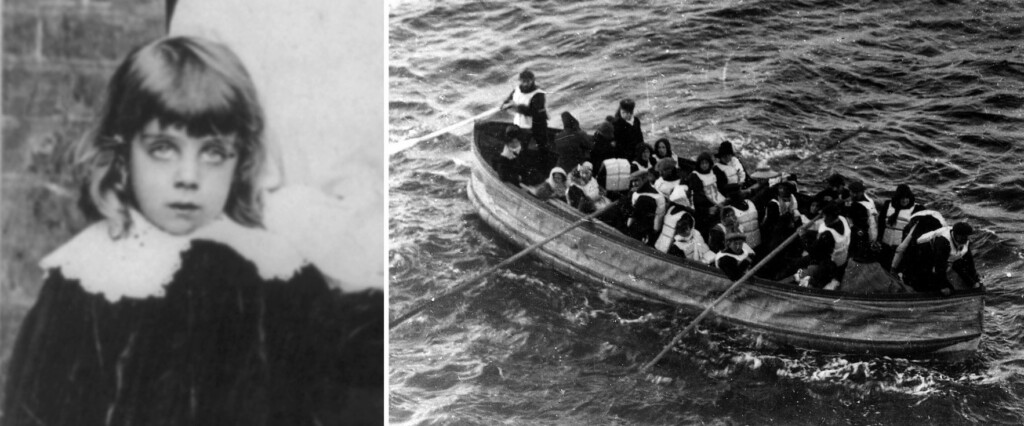

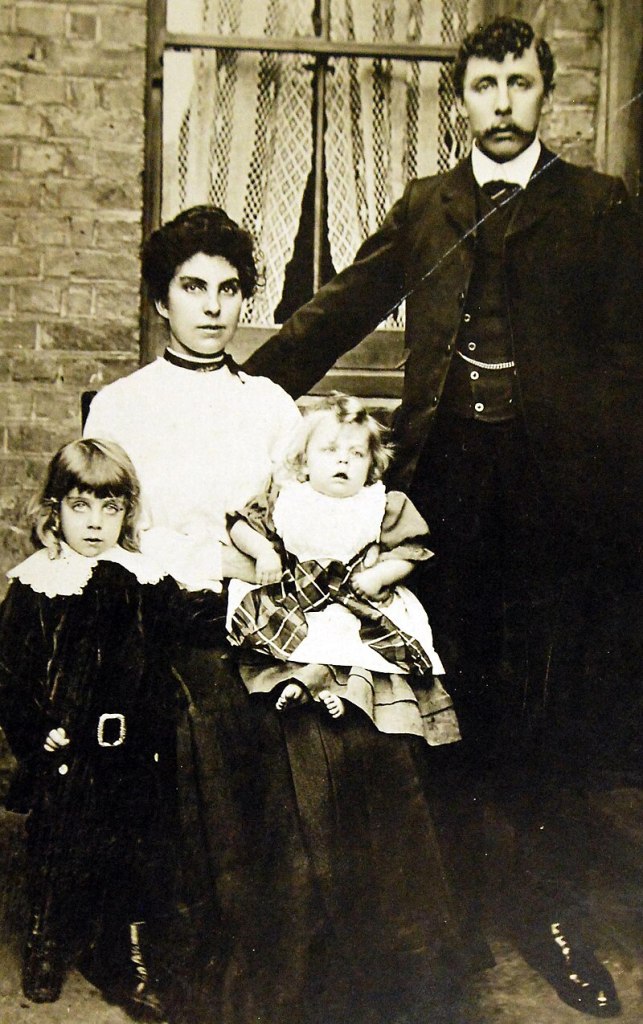

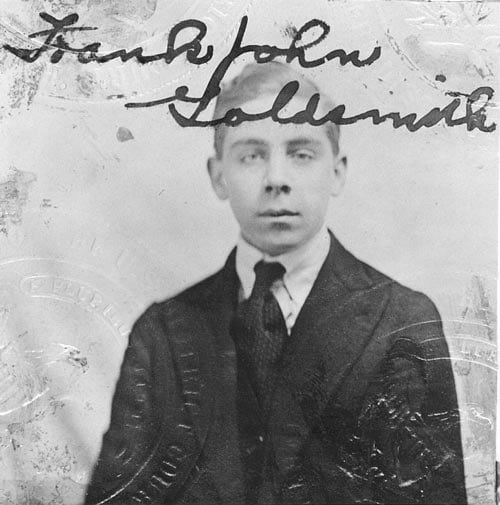

The week before that milestone grand opening day, some 3,700 miles away, a nine-year-old British boy named Frank John William Goldsmith was preparing for the trip of a lifetime. Frankie was born in Strood, Kent, England, the eldest child of Frank and Emily Goldsmith. Between 1908 to 1911, most of the extended Goldsmith family emigrated to the US, settling in Detroit. In the spring of 1912, Frankie’s parents decided to join them. The Goldsmith family boarded the New York City-bound RMS Titanic in Southampton as third-class passengers. During the first three uneventful days aboard ship, Frankie spent his time playing and exploring the ship with other similarly aged English-speaking third-class children. The boys ran the decks, climbed the baggage cranes, and wandered down to the boiler rooms to watch the stokers and firemen at work. Of these boys, only Frankie and one other survived the sinking.

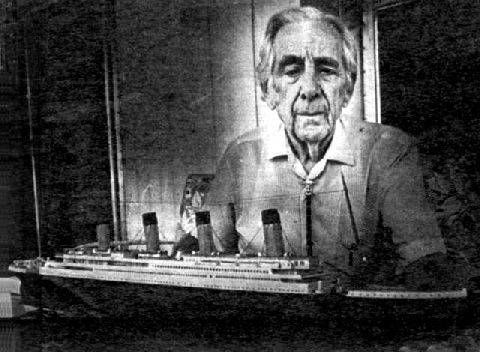

Unsurprisingly, Goldsmith (1902-1982) remembered the exact moment his personal Titanic trauma began for the rest of his life. In a speech to the Rotary Club in 1977, he recalled that he was lacing up his shoes in his third-class passenger cabin when a Titanic officer knocked on, and then opened, the cabin door at about 1:30 a.m. The officer pointed to the ceiling and informed them to put on one of the lifejackets located there. Earlier, Frankie’s father woke his family and informed them to get dressed and prepare to make their way up to the prow of the ship. Ironically, Frankie’s family likely made their way up from their cramped F-deck third-class quarters via the opulent Grand Staircase of the ship. Upon learning that the “Unsinkable Titanic” had struck an iceberg, the family made their way to the forward end of the boat deck, where the “Collapsible C” lifeboat was being loaded. Frankie remembered the lifeboat being surrounded by a ring of crewmen who were only letting women and children on. Collapsible C was the second to last ship to leave, carrying 41 passengers and departing at 1:47 a.m.

Goldsmith wrote of the experience: “Mother and I then were permitted through the gateway. My dad reached down and patted me on the shoulder and said, ‘So long, Frankie, I’ll see you later.’ He didn’t, and he may have known he wouldn’t.” Goldsmith Sr. died in the sinking; his body was never recovered. Goldsmith wrote a book about his Titanic experience, published posthumously by the Titanic Historical Society in 1991. That book, Echoes in the Night: Memories of a Titanic Survivor, remains the only full account recorded by a third-class passenger.

As their lifeboat floundered in the Atlantic Ocean, to keep her son’s young mind off the unfolding tragedy, Frankie’s mother instructed him to turn his back to the sinking ship and care for an invalid survivor. For forty agonizing minutes, the screams of the doomed passengers echoed across the water. By 2:20 a.m, the RMS Titanic was totally submerged, but helpless survivors lasted another 10 minutes before surrendering to the icy waters. The ship sank two hours and 40 minutes after impact with the iceberg. Collapsible C was picked up by the RMS Carpathia around 6:30 a.m. During those four anguished hours asea, Mrs. Goldsmith busied herself sewing clothes from blankets for women and children who had left the ship in only nightclothes. After being rescued, young Frankie was initiated by RMS Carpathia’s boiler-stokers as an honorary seaman by having him drink a mixture of water, vinegar, and a whole raw egg. Frankie swallowed it in one gulp, and from then on, he proudly considered himself a member of the ship’s crew. Nine-year-old Goldsmith remembered the crewmen telling him, “Don’t cry, Frankie, your dad will probably be in New York before you are.”

Growing up, Goldsmith clung to the hope of his father’s survival. It took him months to understand that his dad was really dead, and for years afterward, he dreamed that “another ship must have picked him up and one day he will come walking right through that door and say, ‘Hello, Frankie.’” Alas, he never saw his father again. Throughout Goldsmith’s life the Titanic became both a dream and a nightmare. At times, he would suddenly start talking uncontrollably about that midnight, how he grabbed some candy when leaving their cabin; how, as his descending lifeboat passed a porthole, he saw teen-age crew members playing hide and seek; how the Titanic shot off rockets as if it were the King’s birthday. An adolescent memory of his lifeboat rowing hard after the receding lights of a foreign fishing boat, fleeing the disaster lest its illegal presence become known. The endless, anxious nail-biting sick-feeling of survivor’s guilt that never goes away.

Upon arrival in New York City, Frankie and his mother were cared for by the Salvation Army, which provided train fare to reach their relatives in Detroit. They moved to a home near the newly opened Navin Field, home of the Detroit Tigers. However, unlike most 9-year-old boys, Frankie was never a big fan of baseball. Within easy earshot of the new ballyard, every time Frankie heard the crowd erupt in cheers during a game, he cringed. The sound reminded him of the screams of the dying passengers and crew in the water just after the ship sank; as a result, he never attended Tigers baseball games. Although the acronym PTSD is a more recent generational term, it is nonetheless real. Post-traumatic stress disorder exists as a mental health condition caused by an extremely stressful or terrifying event. PTSD can be caused by either being a part of it or by witnessing it. PTSD may include flashbacks, nightmares, severe anxiety, and uncontrollable thoughts about the event. Nearly everyone knows someone who has suffered from, or continues to battle against, the mysterious (often undiagnosed) condition. It can be a combat war veteran friend who avoids July 4th celebrations or a family member who avoids hospitals due to the loss of a loved one to cancer or another devastating disease. The point is, as I’ve always preached, history matters, and many of the daily hardships we face today have been outlined by our ancestors.

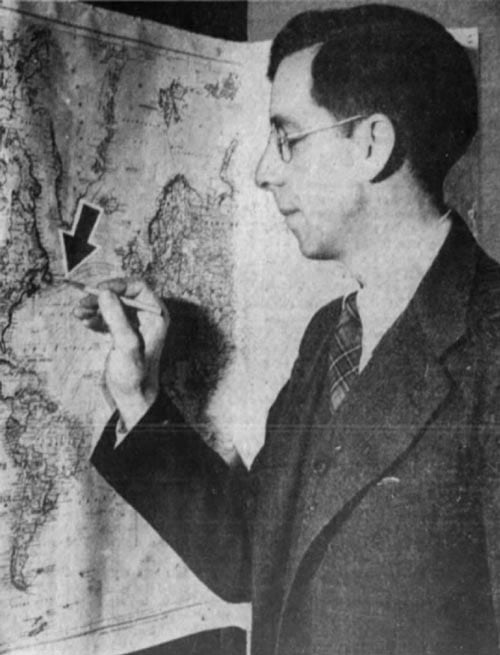

Frankie married Victoria Agnes Lawrence (Goldsmith) in 1926, and they had three sons: James, Charles, and Frank II. During World War II, Frankie served as a civilian photographer for the U.S. Army Air Corps. After the war, he brought his family to Ashland, Ohio, and later opened a photography supply store in nearby Mansfield. Goldsmith died at his home in 1982, at age 79. His ashes were scattered over the North Atlantic, above the site where the Titanic rests.

Frank John William Goldsmith Jr. was just another immigrant child when he survived the tragic sinking of the Titanic. For the remainder of his life, the fatherless boy could never enjoy the cheers of a crowd, regardless of the occasion. Every loud exuberant roar transported him back to that dark April night in 1912. To Frankie, the sound echoed the screams and cries of passengers fighting for their lives in the icy Atlantic. Goldsmith carried the weight of that association with him for the rest of his life. So my friends, when you encounter a neighbor, a friend, a relative, or an immigrant, remember you take them as you find them. Their story might run a little deeper than you think.