Original Publish Date February 29, 2024.

https://weeklyview.net/2024/02/29/they-stole-charlie-chaplins-body/

Two score and six years ago, a pair of hapless unemployed European auto mechanics crept silently into a small country graveyard in Corsier-sur-Vevey, Switzerland under cover of darkness. On the night of Wednesday, March 1, 1978 (and into the early morning of March 2), a 24-year-old Polish refugee named Roman Wardas, and his partner in crime, 38-year-old Bulgarian self-exiled refugee Gantscho Ganev slithered through the small graveyard dressed entirely in black, carrying torches and shovels in search of their prey: Charlie Chaplin. Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin KBE (born April 16, 1889) may only have been 5 foot four inches tall, but he was one of the true giants of the Golden Age of Tinseltown.

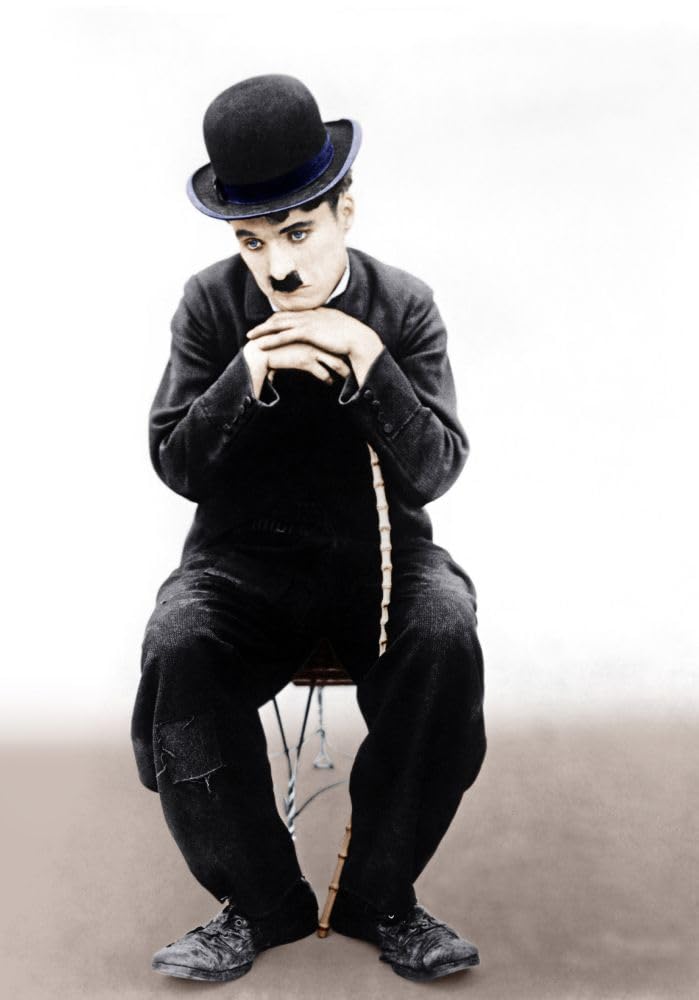

Although today’s fans may think of Chaplin as a uniquely American comic actor, filmmaker, and composer from the silent movie era, in truth, he was born in England, the product of an alcoholic failed actress mother and an absent Ragtime-singing father. Chaplin’s childhood in London was wrought with poverty and hardship. The household constantly struggled financially, as a result, young Charlie was sent to a workhouse twice before the age of nine. At 14, his mother was committed to a mental institution leaving Charlie alone to fend for himself for a time until his older brother Sydney returned from a 2-year stint in the British Navy. Chaplin began performing at an early age (by his recollection at 5 years old) touring music halls and later working as a stage actor and comedian. He dropped out of school at 13 and by the age of 19, he was signed to the Fred Karno company, which took him to the United States. Karno, a British slapstick comedian who played the American Vaudeville circuit, is credited with popularising the custard-pie-in-the-face gag. To circumvent stage censorship in the Victorian Era, Karno developed a form of sketch comedy without dialogue. A skill Charlie Chaplin quickly perfected.

By 1914, Chaplin broke into the film industry with Keystone Studios, where he developed his Tramp persona and quickly attracted a large fan base. By the end of that year, when Chaplin’s contract came up for renewal, he asked for $1,000 a week ($31,000 today), an amount studio head Max Sennett refused, declaring it was too large. The Essanay Film Manufacturing Company of Chicago sent Chaplin an offer of $1,250 ($38,000 today) with a signing bonus of $10,000 ($307,000 today). By 1915, “Chaplinitis” was a cultural phenomenon. Stores struggled to keep up with demand for Chaplin merchandise, his tramp character was featured in cartoons and comic strips, and several songs were written about him. As his fame spread, he became the film industry’s first international star. In December 1915, fully aware of his popularity, Chaplin requested a $150,000 signing bonus (over $4.5 million today) from his next studio, even though he didn’t know which studio it would be.

He received several offers, including Universal, Fox, and Vitagraph, the best of which came from the Mutual Film Corporation at $10,000 a week (about $16 million a year today) making the 26-year-old Chaplin one of the highest-paid people in the world. (For example, President Woodrow Wilson earned $75,000 per year.) Mutual offered Chaplin his own Los Angeles studio to work in, which opened in March 1916. With his new studio came complete artistic control, resulting in fewer films (at one point he had been churning out a “short” per week). His Mutual contract stipulated that he release a two-reel film every four weeks, which he did. But soon, Chaplin began to demand more time and, although his high salary shocked the public and was widely reported in the press, Chaplin upped his game, producing some of his most iconic films during this era. By 1918, he was one of the world’s best-known figures. However, his fame did not shield him from public criticism.

Chaplin was attacked by the British press for not fighting in the First World War. Charlie countered those claims by stating that he would fight for Britain if called and had registered for the American draft, but he was never called by either country. It helped blunt the critics when it was discovered that Chaplin was a favorite with the troops and his films were viewed as much-needed morale boosters. In January 1918, Chaplin’s contract with Mutual ended amicably. Next, Chaplin signed a new contract, this one with First National Exhibitors’ Circuit, to complete eight films for $1 million (a staggering $22 million today). He built a state-of-the-art studio on five acres of land off Sunset Boulevard, naming it “Charlie Chaplin Studios” and once again Chaplin was given complete artistic control over the production of his films. The slow pace of production frustrated First National and when Chaplin requested more money from the studio, they refused. Defiantly, Chaplin joined forces with Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and D. W. Griffith to form United Artists in January of 1919. The name said it all, as it enabled the four partners to personally fund their pictures and maintain complete artistic control. Chaplin offered to buy out his contract with First National but they refused, insisting that he complete the final six films owed.

Lucky for us, Chaplin acquiesced, and after nine months of production, The Kid was released in May of 1920. It is considered a masterpiece and costarred four-year-old Jackie Coogan (Uncle Fester from the Addams Family). At 68 minutes, it was Chaplin’s longest picture to date and one of the first to combine comedy and drama. It was also the first of Chaplin’s films to deal with social issues: poverty and parent-child separation. Chaplin fulfilled his contract with First National and, allegedly after being inspired by a photograph of the 1898 Klondike Gold Rush, and hearing the story of the ill-fated California Donner Party of 1846–1847, he made what may be his most remembered film: The Gold Rush. Chaplin’s film portrays his Tramp as a lonely prospector fighting adversity and looking for love. Filming began in February 1924, costing almost $1 million ($17.5 million today), it was filmed over 15 months in the Truckee mountains (where the Donner Party met their doom) of Nevada with 600 extras, extravagant sets, and special effects. Chaplin considered The Gold Rush his masterpiece, stating at its release: “This is the picture that I want to be remembered by.” Opening in August of 1925, it became one of the highest-grossing films of the silent era, with a U.S. box office of $5 million (almost $89 million today). The comedy contains some of Chaplin’s most iconic scenes; the Tramp eating his leather shoe and the “Dance of the Rolls”.

Over the next few years, Chaplin was one of the few artists to make a successful transition from silent films to “talkies”. At first, Chaplin rejected the new Hollywood craze preferring instead to work on a new silent film. When filming of City Lights began at the end of 1928, Chaplin had been working on the script for nearly a year. City Lights followed the Tramp’s love for a blind flower girl and his efforts to raise money for her sight-saving operation. Filming lasted 21 months, during which time Chaplin slowly adapted to the idea of sound when presented with the opportunity to record a musical score for the film, which he composed himself. When Chaplin finished editing City Lights in December 1930, silent films were fast becoming a thing of the past. Although not a “talkie”, City Lights is remembered for its musical score. Upon its release in January 1931, City Lights proved to be another financial success, eventually netting over $3 million during the Great Depression ($57 million today). Although Chaplin considered The Gold Rush his legacy, City Lights became Chaplin’s personal favorite and remained so throughout his life. Although City Lights had been a rousing success against seemingly insurmountable odds, Chaplin was still unsure if he could make the transition to talking pictures. After all, Chaplin’s stock in trade since his days with the Fred Karno Company had been the art of gesture to tell his stories. And he did it better than anyone else ever.

In 1931, his state of uncertainty led him to take an extended holiday from filmmaking during which Chaplin traveled the world for 16 months, including extended stays in France and Switzerland, and a spontaneous visit to Japan. On May 15, 1932, the day after Chaplin’s arrival, Japanese Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi was assassinated by ultra-nationalists aligned with the Japanese military, marking the end of civilian control over the government until after World War II. Inukai was shot by eleven junior Navy officers (most of whom were not yet twenty years of age) in the Prime Minister’s residence in Tokyo. Inukai’s last words were “If we could talk, you would understand” to which the assassins replied, “Dialogue is useless.” Astonishingly, the original plan included killing Charlie Chaplin-who was Inukai’s guest-in the hopes that this would provoke a war with the United States. Luckily, at that deadly moment, Chaplin was away watching a sumo wrestling match with the prime minister’s son. Chaplin’s vacation abruptly ended and he returned to Los Angeles. But life would never be the same for Chaplin. This political awakening would remain with him for the rest of his life.

Assassination plans notwithstanding, the European trip had been a stimulating experience for Chaplin. It included meetings with several of the world’s prominent thinkers and broadened his interest in world affairs. The state of labor in America had long troubled him. Although not a Luddite by any means, the inequities of life caused him to fear that capitalism and machinery in the workplace would eventually increase unemployment levels. It was these fears that led Chaplin to develop a new film: Modern Times. The film features the Tramp and Hollywood ingénue Paulette Goddard (Charlie’s future bride) as they struggled through the Great Depression. Chaplin intended this to be his first “talkie” but changed his mind during rehearsals. Just like Modern Times, it employed sound effects but almost no dialog. However, Chaplin did sing a song in the movie, which gave his Tramp a voice for the only time on film. Modern Times was released in February 1936. It was one of the first movies to adopt political references and social realism. The film earned less at the box office than his previous features ($1.8 million-$22 million today), but it was released at the height of the Great Depression almost a decade after Al Jolson’s Jazz Singer (the first “talkie”) hit the screens.

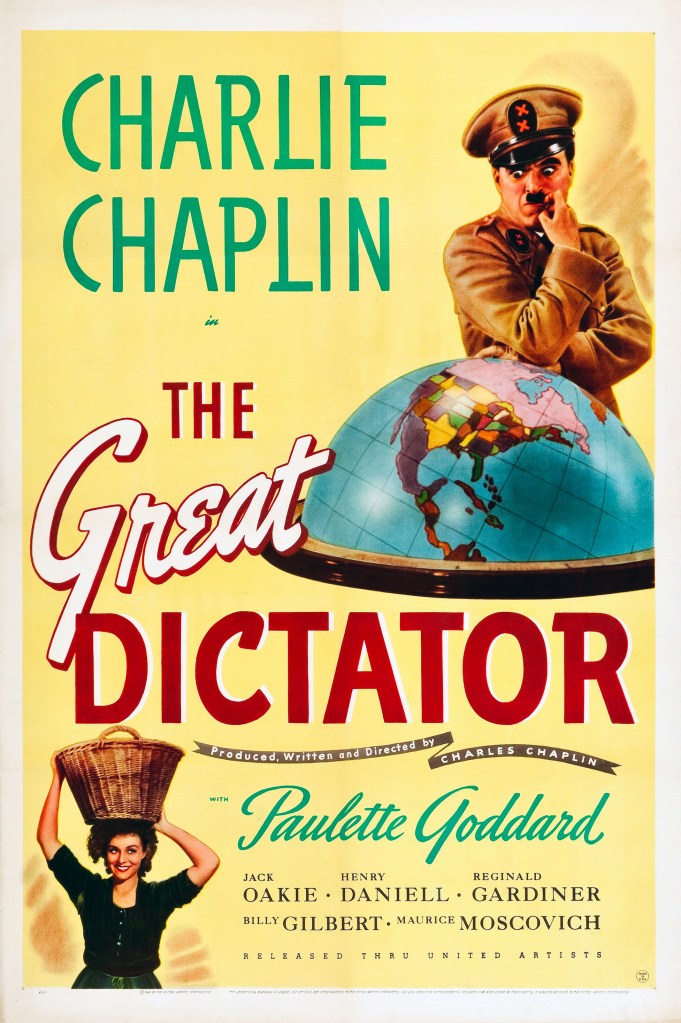

The next few years saw Chaplin withdraw from public view amid a series of controversies, mostly in his personal life, that would change his fortunes and severely affect his popularity in the States. Not the least of these was his growing boldness in expressing his political beliefs. Deeply disturbed by the surge of militaristic nationalism in 1930s Europe, Chaplin simply could not keep these issues out of his work. The ever-increasing state of hostile journalism in the US had already drawn tenuous parallels between Chaplin and Adolf Hitler: the pair were born four days apart, both had risen from poverty to world prominence, and Hitler wore the same mustache style as Chaplin. As pushback, Chaplin decided to use these undeserved comparisons and his physical resemblance as inspiration for his next film, The Great Dictator, a stinging satire about Hitler, Mussolini, and their brand of fascism. Chaplin spent two years on the script and began filming in September 1939, six days after Britain declared war on Germany. He decided to use spoken dialogue for his new project, partly because by now he had no other choice, but also because he knew it would be a better method to deliver his political message. Making a comedy about Hitler was of course highly controversial, but Chaplin’s financial independence allowed him to take that risk, stating “Hitler must be laughed at.” Chaplin replaced his Tramp with a Jewish barber character wearing similar attire as a slap at the Nazi Party’s rumor that he was a Jew. As a further insult, he also played the dictator “Adenoid Hynkel”, a parody of Hitler.

The Great Dictator was released in October 1940. The film became one of the biggest money-makers of the era. Chaplin concluded the film with a five-minute speech in which he abandoned his barber character and, while looking directly into the camera, pleaded against war and fascism. As a whole, the critics gave it rave reviews, but it made the public uncomfortable mixing politics with entertainment and although a success, it triggered a decline in Chaplin’s popularity in Hollywood. Nevertheless, both Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt liked the film, which they watched at private screenings before its release. FDR liked it so much that he invited Chaplin to read the film’s final speech over the radio during one of his famous “Fireside Chats” before his January 1941 inauguration. Chaplin’s speech became an instant hit and he continued to read the speech to audiences at other patriotic functions during the World War II years. The Great Dictator ultimately received five Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay and Best Actor. It would turn out to be Charlie Chaplin’s last hurrah.

They Stole Charlie Chaplin’s Body! Part II

Original Publish Date March 7, 2024.

https://weeklyview.net/2024/03/07/they-stole-charlie-chaplins-body-part-2/

On March 1 & 2, 1978, 24-year-old Polish refugee Roman Wardas, and his cohort, Bulgarian Gantscho Ganev, aged 38, entered a small country graveyard in Corsier-sur-Vevey, Switzerland to dig up Hollywood movie legend Charlie Chaplin, who had died on Christmas Day of 1977. For this mission, the weather was right out of central casting. At 11:00 pm, the atmosphere was thick with fog, peppered by freezing haar, and plagued by a troublesome mist. As the witching hour approached and into the wee hours, a light rain began to fall augmented by a misty drizzle that morphed into shallow patches of fog. Their search ended at a neat, square, freshly dug plot with remnants of floral memorials still clinging to their rusting stands by tattered ribbons. The only sound present was the rippling of the faded satin ribbons flapping in the damp breeze.

Although they didn’t realize it, at that moment, the woebegone duo were at the zenith of their existence. They stood, staring at the grave, hands clasped atop the shovel handles, chins resting on their perpetually oil-stained knuckles. Like pirates from a bygone era, they knew a treasure was beneath their feet. For a few moments, the luckless pair dreamed of their shared idea of setting up their very own car repair shop. A sleek-looking modern white tile garage fitted with a vehicle lift, an automatic tire changer, and an air compressor equipped with a large bevy of shiny pneumatic tools ready to serve a large affluent clientele. A shared smile appeared slowly on each man’s face as they turned to each other and nodded. The first step was obvious: start digging. Atmospheric conditions aside, the two were already wet with a cold sweat. Soon the slap-sling sound of dueling shovels drowned out the usual sounds of the night. As they sunk ever-lower into the earth, the horizon disappeared around them and the panic of not knowing what was going on above them began to set in.

Finally, a shovel hit paydirt. A dull thud in the earth signified that they had hit the jackpot. Shovels gave way to hands and hands gave way to fingers as they quickly excavated the object of their grisly search. It was a 300-pound oak coffin which, although dirty, was remarkably intact. The handles still “handled”, and the lid remained closed. These two burly, jobless grease monkeys hefted the coffin out of its eternal resting place and carried it across the cemetery. As they trod, huffing, puffing, and groaning with each labored step, it must have presented an unearthly vision. The men busting through stage curtain sheathes of banks of fog-like characters in a Universal monster movie unkowing what was waiting for them in each clearing from which they emerged. Sliding the coffin into the back of their station wagon, they quickly jumped into the cab and drove off into the darkness of the night. They had done it. They had just stolen the body of the most famous actor in the history of Hollywood. A man so famous that the mere shadow of his waifish tramp-like form was instantly recognizable worldwide: Charlie Chaplin was in the boot of their vehicle.

These two resurrectionists were convinced that their treasure was going to make them very rich, very soon. They arrived at a ransom figure: $600,000 US Dollars (over $2.8 million today). There were a couple of things the grave robbers didn’t count on though. The discovery of the theft of the Little Tramp’s mortal remains sparked outrage and spurred an expansive police investigation. Now, the whole world was watching this tiny isolated Swiss village. But why? The beloved actor who had created the iconic “Tramp” figure so associated with the Golden Age of Hollywood had been out of the limelight since World War II. While Chaplin continued to make films after his classic 1940 movie The Great Dictator, his star never shined as bright as it did during the periods between the two World Wars. Nonetheless, despite the sometimes sordid details of his love life (he was married 4 times between 1920 and 1943 and was rumored to have had many affairs) and the sensational amounts of money he commanded (The Great Dictator grossed an estimated $ 5 million during the Great Depression-a staggering $110 million in today’s currency), Chaplin remained a beloved figure to generations of fans worldwide.

Looking back, it is easy to understand why. Social commentary was a recurring feature of Chaplin’s films from his earliest days. Charlie always portrayed the underdog in a sympathetic light and his Tramp highlighted the difficulties of the poor. Chaplin incorporated overtly political messages into his films depicting factory workers in dismal conditions (Modern Times), exposing the evils of Fascism (The Great Dictator), his 1947 film Monsieur Verdoux criticized war and capitalism, and his 1957 film A King in New York attacked McCarthyism. Most of Chaplin’s films incorporate elements drawn from his own life, so much so that psychologist Sigmund Freud once declared that Chaplin “always plays only himself as he was in his dismal youth”. His career spanned more than 75 years, from the Victorian era to the space-age, Chaplin received three Academy Awards and he remains an icon to this day.

Not only did Chaplin change the entertainment industry on film, he changed it in practice as well. At the height of his popularity, wherever he went, Chaplin was plagued by shameless imitators of his Tramp character both on film and on stage. A 1928 lawsuit brought by Chaplin (Chaplin v. Amador, 93 Cal. App. 358), set an important legal precedent that lasts to this day. The lawsuit established that a performer’s persona and style, in this case, the Tramp’s “particular kind or type of mustache, old and threadbare hat, clothes and shoes, decrepit derby, ill-fitting vest, tight-fitting coat, trousers, and shoes much too large for him, and with this attire, a flexible cane usually carried, swung and bent as he performs his part” is entitled to legal protection from those unfairly mimicking these traits to deceive the public. The case remains an important milestone in the U.S. courts’ ultimate recognition of a “common-law right of publicity” and intellectual property protection.

By October of 1977, Chaplin’s health had declined to the point that he required near-constant care. On Christmas morning of 1977, Chaplin suffered a stroke in his sleep and died quietly at home at the age of 88. The funeral, two days later on December 27, was a small and private ceremony, per his wishes. Chaplin was laid to rest in the cemetery at Corsier-sur-Vevey, not far from the mansion that had been his home for over a quarter century. But as we have discovered, Chaplin’s “eternal rest” did not last long. After the two ghouls exhumed the body, they found themselves with a new problem. What do we do now? After all, where does one store a corpse in anticipation of a ransom delivery? Thanks to press reports, the duo were aware that Oona Chaplin (Charlie’s fourth wife after Mildred Harris, Lita Grey, and Paulette Goddard) was also the daughter of the playwright Eugene O’Neill, who had died a quarter century before. Reportedly, Chaplin had left more than $100 million to his widow ($450 million today). So surely she would not object to snapping off $600,000 to get her dearly departed husband back, right? But how long would it take to collect that payout?

The body-snatching duo decided they had to do something with Chaplin’s corpse and quickly. So they found a quiet cornfield outside the nearby village of Noville, near where the Rhone River enters Lake Geneva about a mile away from the Chaplin Mansion. Here they dug a large hole and buried the heavy oak coffin with Chaplin in it. Then they waited until the heat died down. Meantime, rumors were flying. Did souvenir hunters steal the body? Was it a carnival sideshow that stole the Little Tramp? Was Chaplin to be buried in England, as he had once requested? The old Nazi speculation about Chaplin’s Jewish ancestry cropped up theorizing that the corpse had been removed for reburial in a Jewish cemetery. All that was forgotten when the kidnappers called Oona Chaplin demanding a $600,000 ransom for the return of the body. The crooks hadn’t counted on what happened next. Suddenly, the Chaplin family, besieged by people wanting the ransom and claiming they had the body, demanded proof that her husband’s remains were actually in their possession.

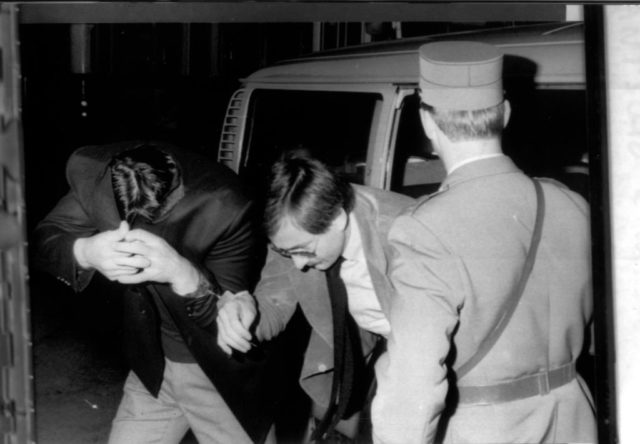

Yikes! Body snatchers Wardas and Ganev had no choice but to schlep back to that field, dig up the coffin, and take a photograph of it as proof that they were the real graverobbers. They quietly excavated the casket and took a photo of it alongside the hole in that cornfield. Then, the two dim-witted graverobbers called the Chaplin Mansion. Well, at least they tried to call. Turns out the number was unlisted so the numbskulls fished around to local reporters, pretending to be reporters themselves, to get the phone number. Needless to say, when the authorities were informed of the scheme, they did not discourage it. At the request of law enforcement, Chaplin’s widow Oona stalled the criminals as she pretended to acquiesce to their ransom demands. At first, Oona refused to pay the ransom, stating “My husband is in heaven and in my heart” arguing that her husband would have seen it as “rather ridiculous”. In response, the criminals made threats to shoot her children. After which, she directed the fiends to the family’s lawyer, who exchanged several telephone calls with the criminals, supposedly while negotiating a lower ransom demand. These stall tactics worked well enough that the police had time to wiretap the phone and trace where the calls were coming from. The savvy criminals used a different telephone box in the Lausanne area for every call, being careful to never use the same call box twice. Undeterred, the investigators enlisted an army of officers to keep tabs on the over 200 telephone boxes in the area. On May 16 (76 days after the grave robbery) the police finally arrested the two men at one of those call boxes.

When taken back to the station, the foolish crooks couldn’t remember the exact spot in the cornfield where they had hidden the coffin. The police swarmed the area with metal detectors and were eventually able to find Chaplin’s remains thanks to the casket’s metal handles. In December of 1978, Roman Wardas and Gantscho Ganev were facing twenty years on charges of desecration of a corpse and extortion. In court, Wardas stated that he had asked Ganev to help him steal the coffin, promising that “the ransom would help them both survive in an environment where employment had not come so readily to them”. Wardas claimed that both men were political refugees and that he had left Poland in search of work, but was virtually destitute in Switzerland. The deranged duo saw the body theft as a “viable financial decision”. The pair had disinterred the coffin and placed it in Ganev’s car, then drove it to the field. Wardas explained in court that “the body was reburied in a shallow grave“ and that he “did not feel particularly squeamish about interfering with a coffin…I was going to hide it deeper in the same hole originally, but it was raining and the earth got too heavy.” In court, the Chaplin family lawyer, Mr. Jean-Felix Paschoud, asked to speak to “Mr. Rochat”, with whom he had exchanged the ransom calls. Wardas hesitantly stood up from his seat and was wished “good morning” by lawyer Paschoud. Wardas explained that it was he, under the name “Mr. Rochat”, who had made the infamous ransom and threatening phone calls to the family.

Ganev, whom the Swiss court described as “mentally subnormal”, testified coldly that “I was not bothered about lifting the coffin. Death is not so important where I come from.” Ganev testified that he had been imprisoned in Bulgaria after trying to flee to Turkey before finally making his way to Switzerland only to find meager wages working as a mechanic. Ganev claimed that his involvement in the crime was limited only to the excavation, transportation, and reburial of the body, and he had no knowledge of any ransom demand. In testimony, Ganev didn’t think the body snatching was any big deal and acted shocked at the public’s outrage to the crime. When sentencing came down, he was given an 18-month suspended sentence. However, Wardas, whom Ganev had identified as the true mastermind behind the body snatching, was sentenced to 4 ½ years of hard labor. Both men wrote letters to Oona expressing genuine remorse for their actions. Oona accepted their apologies answering, “Look, I have nothing especially against you and all is forgiven.”

Ganev and Wardas faded from view and were never heard from again. The only unanswered question remaining: did they ever open the casket? As for Chaplin’s body, it was reburied in the original plot. This time under an impregnable concrete tomb (reportedly six feet thick) to prevent any future grave robbing attempts. Chaplin’s final resting place is neat and simple and now his beloved Oona (who died on September 27, 1991, at the age of 66) rests alongside him. Just to the left of the Chaplin plot is the simple grey headstone of another movie star of the Golden Age: James Mason, a close friend of Charlie Chaplin who lived nearby and died in Lausanne in 1984.

Chaplin’s legacy extended well into the computer age. His iconic Tramp character was utilized as spokes mascot for the original IBM microcomputer from 1981 to 1987 and reappeared briefly in 1991. Not to be outdone, Apple Macintosh utilized Chaplin’s Tramp for their Macintosh 128K (aka “The MacCharlie”) made by Dayna Communications. Although the ad campaign only lasted a couple of years (1985-87) it remains as a testament to the staying power of a century-old mascot created by one man: Charlie Chaplin.

great stuff….

LikeLike